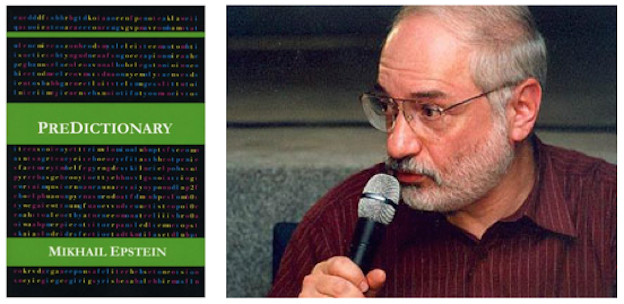

Dear Mikhail Epstein

PreDictionary

PreDictionary

March 28, 2013

Dear Mikhail Epstein,

When I first pulled PreDictionary from the shelf, I glanced at your name and skimmed your bio. My mind registered the following facts: your first name was Mikhail; you had come from Russia; you taught at Emory University. Your last name did not register. I started reading the book.

At some point, I must also have recalled the name of another Russian émigré writer, Mikhail Iossel. I don’t know the other Mikhail, but we are “friends” on Facebook, which is probably the logical explanation for this elision. The next time I was at my computer, I decided to look you up on the Internet to see what else you had written.

I searched for “Mikhail Iossel.” I read his bio. Some of the cursory details are similar to yours. You came to the US in 1990. He came to the US in 1986. He writes in English, you write in English (and Russian). He teaches at a university, you teach at a university. The fact that he did not teach at Emory bothered me, but I thought maybe I had misread something.

It didn’t matter that the book had the name “Mikhail Epstein” written in large white letters on a green band emblazoned across the cover. My mind registered “Mikhail Iossel,” and so I was reading his book. It took several days for me to overcome this blindness and realize that you were not, in fact, Mikhail Iossel. You were you, Mikhail Epstein.

I suspect we should, in the spirit of your work, coin a word to describe the phenomenon of temporary mental blindness to the visual presence of a word caused by a false association with its meaning, the registration of which triggers an inability to read the word on the page before you.

I was thinking that “wordblind” might be a possibility. I looked this up. “Word-blindness” is sometimes used in place of “alexia,” a loss of the ability to read caused by lesions on the brain. My spell-checker tells me “wordblind” is not a word. Maybe in a few years it will be.

I once coined a reflexive verb in Spanish. I volunteered for a year in Ecuador working with children in Quito. One of my duties was teaching physical education to third graders. For an hour each morning, I had to keep them occupied with physical activity. Our classes took place in a concrete courtyard behind the school.

One of the games we played was crab soccer. The children would sit on the ground, feet facing forward, palms on the concrete, fingers pointing behind them. They’d use their knees and palms to raise their torsos a few inches off the ground. I would throw a ball among them and they would play soccer while in the crab position.

At first I found it difficult to order them into this position because my Spanish was a little weak, so I invented a verb. The word for crab in Spanish is “cangrejo.” The word I coined was “cangrejerse,” which means something like “crab yourself” or “make yourself like a crab.” The first time I blew my whistle and shouted the command, “Cangrejense, niños!” they immediately understood my meaning. I was proud.

I have yet to find the term in a Spanish dictionary.

March 29

“ ” made me think about a course I took with Charles Bernstein in graduate school. One night after a poetry reading — I think it may have been by Gerrit Lansing — we all went out to a bar in Buffalo called Gabriel’s Gate. The food there was awful, but the beer was cheap and they had free popcorn, so it was a good place to drink after a reading.

Charles said he had an idea for a new course he wanted to teach in the fall called “Blank.” I asked what he meant. Were we going to read books about nothingness or emptiness or space? He said no, that his idea was to present a blank syllabus and ask students to fill the semester in themselves. The course would have no reading list, no theme, no direction. We would spend the semester, as it were, filling in the blank — or not filling it in. I thought it was a hilarious and inspired idea.

When the fall semester began, a new crop of students arrived with whatever artistic and intellectual aspirations and expectations they’d brought with them. These apparently did not include a sense of humor. While those who had been around reveled in the play and fun of “blank,” the new students rebelled. They wanted a reading list. They wanted a theme. They wanted a direction. They wanted homework!

The arrival of this group of rebels was the moment the fun of grad school ended for me.

March 30

After I finished reading PreDictionary, I wandered around the house thinking about “ .” There was a full moon that night. On my way from the living room to my bedroom, I stopped by my office to plug in my laptop for charging. The moon shone brightly through the glass doors that connect my office to the brick patio in the backyard. I decided to step outside.

I climbed the three steps up to the patio and stared at the moon through the trees. Several tall white pines separate our property from the neighbor’s. I had to peer through the crisscrossed branches to catch a glimpse of the moon. It looked small. Given how much light it was giving off, I would have expected it to be bigger.

I shuffled left, then right, then forward, then back, before I found a spot where I could see the whole moon, unobstructed. I held myself in place and stared at the shining orb. I thought about Mandalas, which made me think of Jung. I wondered if I stared long enough whether I would hypnotize myself or have an out-of-body experience.

Then I started to think about all the “ ” around the moon. The white disc began to waver. A kind of purple corona, a trick of the eye, appeared around it. I shifted left. A small twig obscured my view. I shifted back right. Same thing. I stepped forward, backward, left and right again, but I could not find a clean view.

I tried the opposite. I stepped two steps to the left so that the trunk of a pine blocked my view completely. The light shone against the backs of the trees, throwing them into silhouette. A large limb that had fallen during a hurricane hung in the crotch of a limb about two-thirds of the way up the tree. It became a crucifix. I thought of the scene in Stalker where the writer makes a crown of thorns and places it on his head.

I stepped to the right. I could see the moon again, but I still could not find an unobstructed view. I turned my back to the moon and faced the house. The shadows of the trees danced along the walls. A square of light glowed to my left: the bathroom window. My wife lay soaking in a tub on the other side. On the white blinds covering my daughter’s bedroom window, the shadows of the branches bobbed up and down.

I looked at the stars and I thought of all the “ ” between them. I started to feel a chill. It was mostly quiet. I could hear the hum of cars on the highway in the distance. I took three steps down from the patio, slid open the door. I heard the cats scatter. They must have been watching the whole time.

Edited byLaura Goldstein Michelle Taransky