The author and authority

Daniil Kharms and the Russian Absurd

Russian Absurd: Selected Writings

Russian Absurd: Selected Writings

As some of us are coming to know, the absurd may be characteristic of authoritarian regimes. If so, then the reading of Daniil Kharms is quite urgent in our day. When all norms are violated, it may be that only the absurdist pen can accurately swath through the fuzzy edges of alternative facts and fake news. Russian Absurd is thus a book for our age.

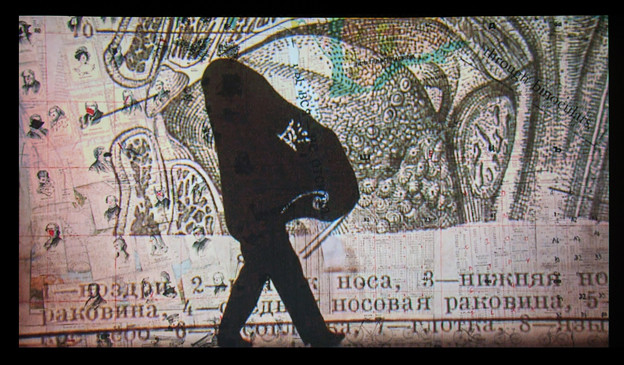

With a devoted following in Russia and a growing cult of readers in the United States, writer Daniil Kharms (pen name of Daniil Ivanovich Yuvachev, 1905–1942) is achieving a fame that would have surprised him. Often compared to his hero Gogol, lionized by surrealists, and called a heritor of Kafka, this poet and master of the short sketch lived a short, vivid, and tragic life, suffering every imagined indignity of a totalitarian regime. Still, Kharms sees this state as an existential, rather than purely political, force of the “absurd manifestation of life.”[1]

At first glance, Kharms seems mainly a writer of the Soviet byt, or way of life, a life and environment marked by poverty and oppression. Given its nature, Soviet life under Stalin often needs but a nudge from Kharms to enter the realm of the absurd, as, for example, in his description of a store with sardine cans but no sardines, or in his tale of a man lying in the corridor of a collective apartment told to go to his room by authorities — but there is no room. However, like Gogol’s independent nose, Kharms’s nudge becomes shove as he punctuates discourses on faith or sex with grotesqueries, including the ultimate grotesque, death. The Kharmsian narrator is never loath to poke his head out from behind the curtain and take things further, with animate corpses and other cosmic hoaxes, to his reductio ad absurdum. He offers refuge from the state and other finalities in dark comedy, as some today take refuge in Saturday Night Live sketches.

Like his predecessors, the Russian Futurists, especially the zaum (such as transrational poets Velimir Khlebnikov and Aleksei Kruchenykh), Kharms’s work is a slap in the face of the public taste ratcheted up exponentially. Kharms especially admired Khlebnikov, calling him the greatest (but still not fully adequate) poet of the twentieth century, and Kharms’s early theorizing shows the zaum philology reminiscent of that poet:

Nouns give birth to verbs and bestow onto verbs independent choice … In this way develops a new generation of parts of speech. Speech, liberated from logic’s course, runs along novel paths, disarticulated from other kinds of speech. The edges of speech shine a bit brighter, so that we are able to see where is the end and where the beginning, otherwise we would become entirely lost. (15)

Armed with the acuity of verbal edges, alogicity in the extreme, and with no mercy toward his searching characters, Kharms developed his implacable narrative voice: “I am interested only in pure nonsense, only in that which has no practical meaning. I am interested in life only in its absurd manifestation. I find heroics, pathos, moralizing, all that is hygienic and tasteful abhorrent” (vii). A fuller refutation of the enforced happy face of Soviet Realism could not be stated.

As part of an inner longing or as one of life’s absurd manifestations, Kharms explores as a constant theme the existence of immortality. In “The Old Woman” (“Starukha”), Kharms’s masterpiece, two men discuss belief:

“But believe or disbelieve in what? In God?” asks Sakerdon Mikhailovich.

“No,” I say. “In immortality.”

“Then why did you ask me if I believe in God or not?”

“Well, simply because asking ‘Do you or do you not believe in immortality?’ sounds somehow foolish,” I say to Sakerdon Mikhailovich and get up from the table. (165)

In another such conversation, an upright citizen shames two conversationalists, telling them that discussing an afterlife is a foolish occupation for two young (Soviet) men.

Shy about sensitivity, Kharms is brutal on the trite. When sentiment or shtamp or cliché poke their heads into a sketch, Kharms’s narrator will abruptly end it midtale. As the protagonist’s situation or depiction approaches “pathos,” the sappy ordinary, the “heroic,” or the “hygienic,” out steps a Kharmsian supernarrator. “This is quite ridiculous,” he says, or “this has gone on long enough,” or “this is a stupid article” and ends his story — apparently midclimax, but exactly when it should be ended. “Sweet Little Lida,” a masterfully drawn portrait of a pedophile, is ended midcrisis by the Kharmsian narrator as too “nasty,” before moralizing can begin.

Kharms uses this technique of stepping in as a supernarrator to pull the plug on things in “The Old Woman.” Its protagonist tries to deal with the presence of death in a “stiff,” the corpse of an old woman in his quarters that won’t go away but does threaten to crawl on all fours at times. The Kharmsian narrator peremptorily ends this longer story with “at this point, I must temporarily break off my manuscript, considering as I do that it has gone on far too long already” (176). Nothing further on immortality is written. Nor does this narrator allow the writer-protagonist of the tale to finish his story within the story; the protagonist is writing a story about a miracle worker, a “tall fellow,” who, like a malevolent God, can, but won’t, perform miracles, not even to save himself. The Kharms supernarrator forces his character to live with death and ends him abruptly, as Soviet life ended many. He censors himself to forestall the sentimental, the expected, even the miraculous. Also edited are genuine sentiment and longing for redemption, self-censored by an author who, perhaps, knew how the world treats these too well.

Denizens of an irrational universe, Kharms’s heroes are attacked by the byt as they eat, work (infrequently), rent, and love. From “An Obstacle”:

“I have very thick legs,” said Irina. “And I’m very broad in the thighs.”

“Show me,” said Pronin.

“I can’t,” said Irina. “I’m not wearing any underwear.”

Pronin knelt on his knees before her.

Irina said, “Why did you get down to your knees?”

Pronin kissed her leg just above the stocking and said, “Here’s why.”

At that moment someone knocked on the door of Irina’s room.

Irina quickly righted her skirt. Pronin got up off the floor and went to stand by the window.

“Who is it?” Irina asked at the door.

“Open the door,” a voice commanded.

Irina opened the door, and in walked a man wearing a black coat and high boots. Behind him were two soldiers, armed with rifles.

“Conversation is forbidden,” said the man in the black coat.

[ … ]

“Everybody out,” he said.

And they all walked out of the house, slamming the apartment door shut. (183–84)

Not surprisingly, Kharms’s diaries of 1937–38 reflect persecution, hunger, prayer, and the lack of a will to live. Russian Absurd also includes Kharms’s NKVD confession, which carefully names only names already known to the secret police. But without political intention, Kharms’s work has outlived the memory of Stalin’s goons. The power of his unsentimental black comedy remains a slap in authority’s face heard round the world. The absurd, meeting the politically unbelievable, remains the best sendup of the authoritarian, then and today.