Activist documentary poetics

On Susan Briante’s ‘Defacing the Monument’

Defacing the Monument

Defacing the Monument

Susan Briante’s Defacing the Monument is a hybrid creative-critical text that explores the possibilities for documentary poetics to interrupt injustice. Briante weaves together excerpts of documentary poems, theoretical texts, news clippings, photographs, scanned documents, her own family stories, workbook pages, maps, spreadsheets, Facebook posts, and anecdotes about activism in a kind of documentary commonplace book. She focuses her attention on the crisis at the US-Mexico border, describing the increasing death toll resulting from the militarization of the border and the criminalization of illegal crossing under Operation Streamline. As a White woman who is the descendent of Italian immigrants, Briante explores the longer histories of immigration and race in America in order to simultaneously show the shifting definition of “Whiteness” throughout the nation’s history and to reveal the ways her own ancestors ultimately benefitted from their Whiteness. The text pivots back and forth between the personal and the political, and, rather than telling the stories of individual migrants, Briante emphasizes her own (and her reader’s) complicity in systems of violence. Acknowledging the way social media has “lulled us into a false sense of ‘activism,’” Briante concludes that “[o]ur capacity to witness has increased at a disproportionate rate in relation to our ability to effect change.”[1] Defacing the Monument is Briante’s attempt to discover how documents, poetry, witness, and activism can intersect in a meaningful way.

The text is divided into three primary sections addressing erasure, relation, and hauntology; these sections are made up of a combination of full-bleed black and white images and short prose vignettes, each labeled with a large black number (1–40). The book concludes with an epilogue on list making and documentation and an appendix that contains further reading, reflection questions, and writing exercises for documentary poets. In spite of its antimonumental title, Defacing the Monument makes visible a solidly forming archive of twenty-first-century documentary poetry and criticism. Through collage and citation, Briante gathers the threads of conversations about documentary poetics that have transpired across an unwieldy network of scattershot blog posts, conference panels, and one-off articles. Her hybrid essay-poem lucidly places creative work by Muriel Rukeyser, James Agee, M. NourbeSe Philip, Claudia Rankine, Layli Long Soldier, and Solmaz Sharif in conversation with critical work by Édouard Glissant, Judith Butler, Saidiya Hartman, Philip Metres, and Joseph Harrington. Assembling her own archive, Briante reads representative excerpts from well-known documentary poems in order to identify their methods, offering a kind of generalized set of practices to her imagined audience of documentary-poet readers. Like Michael Leong’s monograph on “documental poetics” that was released just two months before Briante’s collection, Defacing the Monument recognizes that poetry participates in the work of cultural memory by defacing existing “monuments,” as well as by “monumentalizing obscure, marginalized, or contested documents.”[2]

For example, in the section titled “Frames, Erasures, Graffiti,” Briante reads an excerpt from Long Soldier’s Whereas in which Long Soldier redacts words referring to Indigenous culture from the US government’s official apology to Native peoples and then reproduces the redacted words as a poem on their own page. Through her analysis, Briante demonstrates how both erasure and interpellation enable the poem to become “a work of protection” (30). In the section called “Guidestars, Tangles, Hauntologies,” an excerpt from Philip’s Zong! models how the documentary poet can “access the stories excluded from the text or trapped within them” by listening, investigating, and expanding their sources of information to include “ghosts, gossip, dream, sensation, gut-talk, myth” (93). By bringing these well-known documentary texts into her discussion of US immigration policies, Briante extends the scope of her book from a single topic to a larger reflection on the limits of documentary poetics as a mode of critique. On the one hand, this shows how racism and capitalism are the shared root of a variety of problems (from genocide and slavery to the deaths of hundreds of migrants attempting to cross the desert). On the other hand, Briante’s own ars poetica often eclipses her stated subject. As a result, a book that initially appears to be a documentary project about immigration soon morphs into a tentative manifesto on documentary ethics.

Part of the attraction of documentary poetics is its ability to shift nimbly between the personal and the political. And yet, that ability is also a liability. The positionality of the poet becomes incredibly important when a poem draws on documents, because recontextualizing and altering documents means recontextualizing and altering the words of another. In Defacing the Monument, Briante sets out to answer the question: “How do I represent a story that’s not mine?”[3] As the cocoordinator of the University of Arizona’s Southwest Field Studies in Writing Program, Briante takes regular trips with her students to the US-Mexico border to “engage in reciprocal writing and research projects” (162). The field studies program creates an immediate tension between who is speaking and whose story is being told, as these trips often become the basis for creative writing projects by students in the program. Hearing the stories of migrants and witnessing how they are criminalized by the US government, Briante and her students wonder: “How can we amplify voices without turning other people’s stories into commodities, without reaffirming the faulty myth of ‘giving voice’? […] We know that writing will not be enough” (62). Briante acknowledges the wide range of ways writers have handled the ethical issue of writing about the border, from donating the money they make to not writing about their visits at all.

Briante’s approach to the ethical problem of documentary poetics is twofold: she interrogates her own subject-position and its complicity in larger systems of injustice, and she backs up words with activism. In other words, rather than trying to represent a story that’s not hers, she ultimately presents the story of how she is implicated in others’ stories:

When I say we need to understand our documents as well as ourselves within the web of power and processes that produce them,

I do not mean I can speak for the migrant women in the shelter no matter how much I feel for them. I do not mean I get to imagine my way into their stories. I mean my compassion must compel me to see the ways directly or indirectly that I am implicated in their suffering. (66)

Recognizing the failures of previous documentary projects, Briante aims to “mov[e] away from taking up the voice of the oppressed to take a look at her own relationship to oppression.”[4] She reckons with her own positionality as a poet, professor, and the White granddaughter of Italian immigrants, while also providing searching questions for practicing documentary poets to consider whether a story is “theirs to tell.” Briante emphasizes that White writers, in particular, need to “recognize the violence our positions enact even unwittingly” (67). She draws on Saidiya Hartman’s reading of the scene in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men when James Agee becomes aware of the violence of his own Whiteness as a Black couple reacts in fear when he runs after them to ask them for help unlocking a church. “What distinguishes this moment,” Hartman writes, “is the artist’s willingness to admit and to own the violence of the encounter.”[5] Briante takes Hartman’s words as a call for the White writer “to seek that self-reflective and self-destructive trembling […] instead of waiting to be confronted” (67). In order to do this, she connects her personal experiences of citizenship and privilege to Édouard Glissant’s concept of opacity. Opacity is what stands between the documentary poet and unethical acts of appropriation that make false claims of “giving voice”:

Venn diagrams make an eclipse, the beginning of an opacity, a

shadow thrown between us:

from which we might discern our relations. (88)

Briante reproduces this Venn diagram in every section of her book; each time asking the documentarian to consider a different aspect of their own positionality in relation to their subject. In this iteration, the Venn diagram complicates a moment of connection — the center created by the overlapping circles — by recasting it as shadow. For Glissant, the right to opacity is “not merely the right to difference” but the right to “subsistence within an irreducible singularity.”[6] However, rather than shutting down action or Relation, the shadow can move us to acts of solidarity, born out of compassion, which, unlike empathy, does not metabolize the experience of the other: “To learn from opacity is to learn from what we do not know, is to learn without mastery. Glissant reminds us that opacity ‘can make me sensitive to the limits of every method’” (87).

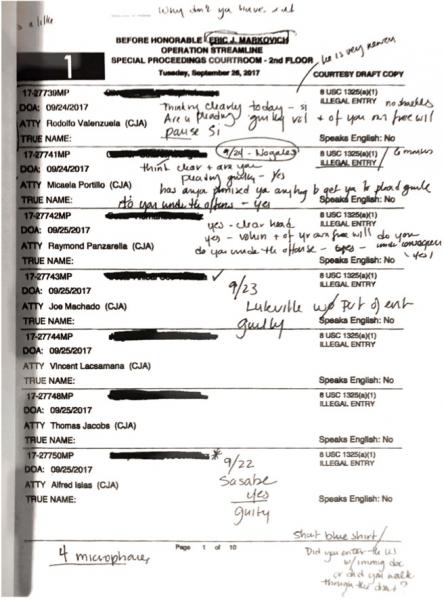

Perhaps one way to think about Defacing the Monument’s ethics is to think about what has been left out. Rather than appropriating and reproducing the stories of individuals without their permission in an act of “vulture work” (74), Briante presents anecdotes of her meetings with migrants, coupled with copies of the legal documents that have multiplied around instances of illegal border crossings. She then sets out to deface those documents in order to reveal their own inhumane omissions. Defacing the Monument opens with scans of the calendar of court proceedings in Tucson, Arizona, followed by an arresting two-page, black-and-white image of the border wall in Nogales, Sonora. Sitting in the back of the courtroom, Briante takes in the dehumanizing repetition of Operation Streamline: the program that redefined illegal entry as a criminal (rather than administrative) issue and established mass plea bargains where as many as seventy-five migrants can be tried in a single day. Originally introduced as a temporary measure in 2005, the program expanded to a massive size under Obama and thrived during the Trump administration. A strict script transforms a space that claims to enact justice into a manufactured farce. In one poem, Briante reproduces the questions the court asks each migrant seven times, with only the date and location signaling any difference:

Do you understand the rights that you are giving up, the consequences

of pleading guilty and the terms of your written plea agreement? Are you

pleading guilty voluntarily and of your own free will? Are you a citizen of

the United States? On or about March 17, 2017 did you enter the United

States from Mexico near Nogales without coming through a designated

port of entry? How do you plead to the charge of illegal entry? (17)

These questions are asked in quick succession, and many of the migrants, most of whom do not speak English, and some of whom only know Spanish as a second language, are unable to keep up. At the end of the day, “Each migrant leaves the proceedings with a criminal record. // In this sense, the process is documentary” (21). Thus, rather than streamlining, the operation bags out, overfilling prisons, burdening the courts, expanding the budget, and raising the migrant death rate. As Briante asserts, however, the “proceedings are successful in their goal: they turn migrants into criminals” (21).

Defacing the Monument delineates a powerful parallel between the state’s documentary violence — “a document can pull a nation out from under you” — and the poem itself as an archive.[7] For Briante, a document in and of itself is neutral, “a blank slate upon which any story can be written” (26). Because of this, documentary poetics plays an important role in framing documents in order to “[u]nderstand events as part of larger systems and legacies” (26). As the title Defacing the Monument suggests, Briante is not interested in adding documents to this burgeoning archive. The section “Frames, Erasures, Graffiti” points to what exceeds the system of documentation by defacing the documents themselves. The court schedule that appeared on the first page of the section was already scribbled over with Briante’s notes as she witnessed the proceedings. Ten pages later, the document reappears overlaid with yet another document: the headline from a People for the American Way blog post — “Trump’s America: For-Profit Prisons, Immigrant Detention and Shady Political Donations” — appears above a frayed American flag blown taut behind a metal fence and obscured by a mess of barbed wire. Through the palimpsestic jumble, the headline’s juxtaposition with the catalog of criminalized migrants suggests that the program’s carceral excess is for profit, not justice. These documentary defacements culminate with an almost illegible image, in which the court’s questions to the migrants increasingly overlap until they almost entirely blot out the white of the page, a visual allusion to Glenn Ligon’s 1992 print “Untitled (I Feel Most Colored When I Am Thrown Against a Sharp White Background).”[8] In all of these images, graffiti, as a form of “overwriting,” generates excess that literally becomes opaque. Drawing on early documentary poet Muriel Rukeyser’s oft-quoted phrase “poetry can extend the document,” Briante outlines a documentary ethics that works through both addition and subtraction: “We must not replicate the elisions of the state. As poets and documentarians, we can extend the document or deface it to discern its limits and to situate it against those other sources that broaden its narrative, reveal its omissions, lay bare its brutality” (34).[9] Briante demonstrates how defacing a document can be achieved either by bringing in additional sources (the People for the American Way blog post) or by simply replicating the words of the original document, folding it in on itself until they reach the point of absurdity.

Figure 1. Operation Streamline court schedule scan from Defacing the Monument (13).

Figure 1. Operation Streamline court schedule scan from Defacing the Monument (13).

After laying the groundwork for her documentary defacement in the first section, Briante turns to her own family history in section two, “Writing in Relation,” as a means of simultaneously taking responsibility for her privilege and expanding the historical frame for conversations about immigration in America. Briante’s Italian immigrant grandparents faced discrimination (eleven Italian Americans were lynched in Louisiana around the time her grandfather arrived there), but Briante recognizes that their Whiteness eventually enabled them to assimilate and pass down the privilege of unquestioned citizenship to their descendants: “Although I live on occupied lands, nobody asks for my papers” (54). Briante enumerates the ways in which “our documents as well as ourselves [are implicated] within the web of power and the processes that produce them” (47). Although Briante sees unearthing her family history as crucial ethical work for locating herself in “the web of power,” at times, the connection between her family narratives and the ethical stakes of documentary poetics is less clear. For example, in the final section, “Epilogue: Stopped Clocks, Rolling Videos,” she pairs a catalog of the items on her mother’s bedside table when she died with Facebook posts cataloging the atrocities that Trump committed while in office as a way of arguing for the importance of documentation as a response to trauma. She reflects on whether Trump’s election to office counts as a “traumatic event,” and then uses the experience of grief after each of her parents’ deaths as a kind of framing metaphor to discuss the feeling of loss felt around the unfulfilled (never fulfilled) possibility of American equality. These grief-filled prose poems about the loss of her parents sometimes feel as if they are straining to become a project of their own, rather than an example of documentary practice. As a result, I found the epilogue to be the least effective section of the book. Unlike in section two, where writing about her ancestors’ experience with racism and, ultimately, successful assimilation as (White) Americans served to reveal how Briante’s own positionality and privilege informed her understanding of immigration and race at the US-Mexico border, creating a parallel between the loss of one’s elderly parents and trauma of the Trump presidency feels unrelated and trivializes the real threat of violence for people of color, women, immigrants, and LGBTQ communities ushered in by his election.

At the same time, Defacing the Monument distinguishes itself from the ever-growing crowd of documentary projects through its commitments to self-reflexivity, pedagogy, and, most critically, activism. Briante says that her “preferred documentary” is “lyrical and useful, observant and subversive, multilingual” (31). She manifests this kind of practical documentary writing in her own text, which posits an audience of documentary poets. I have found Defacing the Monument to be a particularly effective text in the classroom, introducing my students to some of the major conversations in the field of documentary poetics and inviting them to map their ethical relationship to their subject matter via activities in the “Resources, Questions, and Exercises” section that concludes the book. Answering Mark Nowak’s call for documentary poetics “to find its feet outside of AWP and art galleries and instead locate itself (or organize its potential location) on factory floors, in union halls, at political rallies, in collaboration with institutions and organizations,” Briante expands her canon of documentary acts to include protests against ICE and Border Patrol agents by students at the University of Arizona, performance art that makes the border’s violence visible, and “useful” poems, such as those in The Desert Survival Series by the Electronic Disturbance Theater 2.0/b.a.n.g. lab, which was designed to be shared in an app that equips migrants to find water or direction in the desert.[10] “We need to document,” Briante insists, “But without activism, the document (or the list) can become a source of nostalgia as useless as the stopped clock sitting on my living room shelf” (134). In an interview Briante identifies this nostalgic tendency as the source of documentary poetry’s ineffectiveness: “One of the limits of documentary is that it’s obsessed with what’s there and not with what’s possible.”[11] If documentary poetics is going to engage the world, it must do more than preserve the past; it must also imagine futures.

1. Susan Briante, Defacing the Monument, (Blacksburg, VA: Noemi Press, 2020), 68.

2. Michael Leong, Contested Records: The Turn to Documents in Contemporary North American Poetry, (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2020), 41.

3. Susan Briante, “Rekindled: Susan Briante in Conversation With Raquel Gutiérrez,” interview by Raquel Gutiérrez, The Virtual Book Channel (LitHub), June 1, 2020.

4. Susan Briante, “Defacing the Monument,” Jacket2, April 21, 2014.

5. Saidiya Hartman, “Near a Church at Dusk,” (presentation, On Whiteness: A Symposium, June 2018), quoted in Briante, Defacing the Monument, 67.

6. Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1997), 190.

7. Joseph Harrington claims that “If poetry is an archive, then so too is a poem — or any text — and the writer is a kind of archivist.” Joseph Harrington, “Docupoetry and Archive Desire,” Jacket2, October 27, 2011.

8. Ligon’s piece is based on a Zora Neale Hurston quote. It also anchors one section of Claudia Rankine’s documentary collection Citizen: An American Lyric. Glenn Ligon, Untitled (I Feel Most Colored When I Am Thrown Against a Sharp White Background, 1992, etching and aquatint, 25 3/16 x 17 7/16" (64 x 44.3 cm).

9. “Poetry can extend the document” appears as an end note on Rukeyser’s documentary series “The Book of the Dead.” Muriel Rukeyser, The Collected Poems of Muriel Rukeyser (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2005), 604.

10. Mark Nowak, “Documentary Poetics,” Poetry Foundation, April 17, 2010.

11. Briante, “Rekindled.”