Metaphor or more?

Could you provide a brief statement on why (if you do) you think that science/scientific discourse should be incorporated by poets not simply as a source of metaphor but as an independent discipline or set of disciplines? (If you’ve already addressed this in print in some detail, feel free to indicate where that can be found.)

Rae Armantrout: I wouldn’t say that scientific discourse “should be” incorporated into poetry, but, clearly, I think it can be. I tend to incorporate various discourses into my work — anything from popular song lyrics to descriptions of quantum mechanics. I do this as a way of mulling over and interrogating what I hear/read. We all get our view of the world and the universe partly from what we’re told about science. I tend to bring in various things that contribute to the way we construe reality: creation myths, political “news,” and scientific information. (It’s interesting that, even during my adult life, astrophysics and cosmology, in particular, have told us quite a variety of things about the universe. Sometimes their descriptions remind me of the story of the blind men and the elephant. I don’t mean that disrespectfully at all. They change their story as more information or different information becomes available. It’s the people who stick to their story that you have to watch out for.)

I have two answers to the question about metaphor. First, metaphor is “always already” embedded in the language of science. The language of physics, in particular, is math. When a physicist tries to tell us about quantum mechanics, he/she has to use metaphor. What does it mean, for instance, to say that an electron has “spin?” It doesn’t mean that an electron is very like a top. I think one can question the metaphors used by scientists without necessarily doubting that they are describing something real. I think my poems — and here comes a cheesy metaphor — tend to pick at metaphor as one might pick at a scab. Scientific metaphors are certainly fair game. Second, I tend to use metaphor in an unconventional way. My metaphors are seldom proper metaphors at all. I tend to juxtapose two images or two types of discourse and see what sparks fly (metaphor) or what resonance the two parts have between them (metaphor). In a conventional metaphor, there are the “tenor,” i.e. what you’re really talking about and the “vehicle,” i.e. the image or phrase you use to make the tenor more vivid. For instance, when I said that I picked at metaphor as one might pick at a scab, I was really interested in metaphor. The poor scab was a mere vehicle. I wouldn’t use words that way in a poem — or, if I did, it would be deliberately comic. Generally, when I juxtapose two images (discourses, whatever) in a poem, I’m equally interested in both of them; both sides of the metaphorical equation are real for me.

Joan Retallack: Why would one seek poetries that activate permeable borders across disciplines, genres, concepts, and vocabularies of many kinds, including (and of first consideration for our forum) those from sciences, geometries, and other forms of mathematics? I think of the fact that we increasingly know how limited our sensory and cognitive apparatus is. Our species lives on a planet surrounded by other animals that can sense many things we can’t. To go about in this world partly blind, deaf, insensate in innumerable ways to — in all probability — most of what exists in space-time is part of the condition of being human.

Through ingenious artifice, built into procedural methods and technologies (including inventions of specialized vocabularies), our species has been able to extend awareness in extraordinary and surprising ways. I’ll not broach questions of epistemology, e.g., what exactly do we know when we think we know things via experimental and theoretical sciences or math? Whatever the matches (or lack thereof) among our ontologies and epistemologies, the incorporation of science and mathematics into contemporary poetics results in a kind of pop-up dimensionality that I find both essential and delightful. (The same is true, of course, when one draws from other kinds of disciplines — e.g., spiritual, philosophical, historical, and those connected with the other arts.)

When I try to get some perspective on how I’ve used science and math in my work, there seem, so far, to be three main approaches which I’ll briefly comment on.

1. Ecological. This has to do with the sense of one’s embeddedness (in full cognizance of reciprocal alterity) with all those “others” in conditions — global and eco-niched — subject to the same laws of nature, sharing the same pattern-bounded indeterminacy along with trees, streams, oceans, coral, clouds, dolphins, beetles … This means that we are equally subject to chaotic (in the technical sense developed by the sciences of complexity) dynamic equilibria of order and disorder where human agency is a particularly delicate matter. This has led me to think in terms of “poethical wagers” and also to attempt composing language in such a way that I am literally collaborating with principles of chance/order in various degrees of patterning and local unpredictability. I think of the poetry in which I’ve done this as loosely analogous to models of chaos developed by Edward Lorenz, Benoit Mandelbrot, et al. I’m using “analogy” as it is deployed in biology — where “analogous” structures may manifest out of very different evolutionary processes of natural selection (e.g. wings of insects v. wings of birds). Examples of this “ecological” approach are my poem “AID/I/SAPPEARANCE,” and my “Afterrimages” series in which I used procedural operations to transmute language above a visibility line into chance determined fragments below.

The concept of ecopoetics (as playing out in Jonathan Skinner’s journal of that name and elsewhere) has been enormously important in its implicit invitation to experiment with a poetics that acknowledges and enacts ecological embeddedness and its attendant vulnerabilities.

2. Geometries of attention. Every form of geometry — Euclidean, Archimedean Mechanics, Topological, Fractal, etc. draws attention to spatial relations of figures which may be conceptual idealizations, or configurations that actually occur in nature, e.g., “the fractal geometry of nature,” or that address new possibilities among cosmological realities as in the geometries of string theory. I’ve been interested in all of the above but, for our purposes, submitted my poem “Archimedes’ New Light: Geometries of Excitable Species” because it’s language is working through the intimacy (spatial and emotional relations) of bodies caught in schemata of love and war. I happen to find the language of Archimedes — who designed war machines — quite erotic in its attention to intersections of bodies. The war machines conceived by Archimedes did of course observe all the “abstract” principles articulated in his geometry with of course the real consequences all abstractions (counter to their popular reputation) engender. To me, this language becomes more and more imbued with a very strange (perhaps even perverse) emotionality as it becomes its own QED for the fate of the body, for instance: “the.body.inscribed.in.the.cylinder.”

or

“the.prism.the.prism.cut.off.by.the.inclined.plane.”

Because I wanted to bring the eros (music) I experienced in this language (even in translation) into the foreground, I used the medieval practice of separating words with puncta, in order to invoke manuscripts used by choirs singing Gregorian Chants; a form in which terror can turn to ecstasy and vice versa. The language of Archimedes, the geometry of war machines, is very beautiful when sung. The poem could be performed as an oratorio.

3. Numbers: numerical mysticism, numerology, mathematical puzzles, enumeration, etc. Moving outside the scope of words (thinking right now about the question posed by Gilbert: Do you find that words are sufficient for the poetic response/input?) I’ve wanted to explore beyond the vanishing points of language — visual graphics, certainly, but also numbers. The presence of numbers can open up a kind of wormhole to other dimensions. With this in mind, I’ve at times played with words metamorphosing into numbers or algebraic functions. The numbers in “AID/I/SAPPEARANCE,” on the other hand, are there to count and recount the temporal inexorability of unchecked viral infection. Recently numbers come into short poetic proses that are part of a series I’m calling “The Bosch Notebooks.” I’ve included two of these pieces for our collection, “The Magic Rule of Nine” and “The Ventriloquist’s Dilemma.”

The Magic Rule of Nine

Your sonic suit may not be a perfect fit. You’ll learn to

get by. Just don’t assume that all art is all about victory

over death all the time. Not to say one shouldn’t enjoy

not being dead. In the swell of many a meantime,

many have been known to divert themselves with great

success viz. civilizations’ greatest hits. Take the

discovery of “The Magic Rule of Nine.” That the

sums of all the numbers within the sums of all the

multiplicands of 9 up to and including 9 equal 9 is

numerically melodious (bird singing in tree) to the

species that longs for more to it than a first glance

affords. Someone will say if you really think this is

magic you don’t properly understand the decimal

system (bird falls out of tree). Who among us doesn’t

long for magic. Who among us understands the

decimal system.

The Ventriloquist’s Dilemma

Birdsong entered our words and left with migratory

echoes insufficiently dispersed. We weren’t designed

to perceive most of what surrounds us or to fully

understand the rest. Maybe it’s true that differential

equations drove the teenager off the road. The self-

propagating slope remains unhindered in its x-y axis.

It’s really difficult to find the language to say these

things rigorously. Sound waves break on the shore and

make one feel unwelcome. And too, there’s that

conspicuous absence of real metaphors in nature.

Sorry, meant to say, there’s that conspicuous absence

of real nature in metaphors. Someone will always

claim night flew into a tree. The placement of (those)

words in a line.

James Harvey: There’s a poem on the underground in London at the moment “Proud Songsters” by Thomas Hardy, which begins “The thrushes sing as the sun is going / And the finches whistle in ones and pairs …” etc., and ends “Which a year ago, or less than twain, / No finches were, nor nightingales, / Nor thrushes, But only particles of grain, / And earth, and air, and rain.”

This poem for me illustrates the power of science in poetry to dismantle existing structures, and then put them back together again, build them up ‘mechanically’ while at the same time each level of complexity is acted upon equally through ‘the forces of nature,’ questioning the integrity of the structure. At the same time ‘time’ can be played with. In the poem here, the “particles of grain” etc. are what are making the singing birds.

Science offers many opportunities of strangeness in scale and time before resorting to the peculiarities of quantum mechanics. Following on from time, science offers an opportunity of moving the ingredients of a poem around in a space in interesting ways. Eric Mottram in Towards Design in Poetry wrote “Certainly, most concrete poetry abjures the grip of sentence as a main basis of design, and design is a term which art and science have in common.” At first recourse, the two concrete poems that always spring to mind are Christian Morgenstern’s “Fish’s Night Song” and Apollinaire’s “The Little Car.” With freedom of movement, scientific equations when placed inside poems can be a set of instructions and at the same time material that is instructed by that very equation. In the real world this could bring about emergent properties. In a poem, self reference can make a concrete poem, as in the two concrete poems above.

Evelyn Reilly: For me, it’s not so much a matter of “using” or “incorporating” science as having a way of thinking/using language that is formed by science — for example by a sense of perspective that comes from thinking of humans within the context of cosmological space or geological time. I once thought I was going to be a research biologist and in some ways the older I get and the more that planetary disaster parallels my life span, the less distinction I see between biology and poetry, or biology and anything for that matter. I think of the relationship between science and poetry more as a necessary merging of ways of connecting to the world than something so specific (or general) as a source for metaphor. Sometimes I like to merge language drawn from different cultural sources just to see what happens. Lately I’ve been interested in mixing cliches about “identity” with language drawn from genetics and molecular biology in an effort to write a new kind of “personal poetry,” but you could invert this idea and say it’s an effort to find a different kind of “genetic language” as well. Generally I just find it very pleasurable to introduce specialized vocabularies into writing as a means to escape the “poetic,” by which I mean escape my own habits regarding what is means to write “poetry.” Scientific vocabularies, applied science lingos, anything like that helps me get of my rut and makes me more excited about language again. But this applies equally to other vocabularies such as legal vocabularies, architectural and design language, almost anything. For a while I had on my desk an article pointed out to me by Laura Elrick called “The Roots of Empathy: The Shared Manifold Hypothesis and the Neural Basis of Intersubjectivity.” Just glancing at the first page, not even really reading it, made me overexcited in the same way that a poem by Emily Dickinson can. I keep meaning to read this article, but am almost afraid of its potency.

Amy Catanzano: Hello everyone: I recently read Werner Heisenberg’s Physics and Philosophy (1958), where he acknowledges that quantum theory doesn’t have an adequate language beyond mathematics to describe it. He then immediately quotes from Goethe’s Faust, where Mephistopheles says that while formal education instructs that logic braces the mind “in Spanish boots so tightly laced,” and that even spontaneous acts require a sequential process (“one, two, three!”), in truth, “the subtle web of thought / Is like the weaver’s fabric wrought, / One treadle moves a thousand lines, / Swift dart the shuttles to and fro, / Unseen the threads unnumber’d flow, / A thousand knots one stroke combines.” Heisenberg is arguing, of course, that science must be as attentive to imagination as to logic, but he also seems to be suggesting something extraordinary: that novel sciences must have novel languages beyond mathematics that can be used to describe them. To my mind, art/poetry have the ability to not only describe novel theories and expressions of physical reality but invent them as well. Since the primary concern in theoretical physics today is reconciling quantum mechanics with relativity through proposals such as string theory, aspects of which are being tested by the Large Hadron Collider at CERN, I tend to think of poetry as an experiment in physics (the study of physical reality), and experimental physics as a field test for poetry. But that might be my romanticism coming through. Regarding Rae’s comment that she knows of no one who is both a physicist and a poet: I only know of one person who is concurrently practicing poetry and applied science; it looks like he’s been invited to this discussion, so maybe at some point we’ll hear more about how these disciplines get redefined when simultaneously shot through the high-energy particle accelerator …

Catanzano [in response to Rae] [click images to enlarge]:

Peter Middleton: A belated hello. I’ve found the discussion fascinating and would have joined in sooner if I could. What has made it all the more engrossing is that I’m writing a book on American science and poetry since 1945, and taking a long time over it. My ignorance grows and grows the more I read about it. Although the book is still going slowly, several articles have emerged from my early attempts to summarise things. Here is an extract from an essay called “Strips: Scientific Language in Poetry” that appeared in the December 2009 issue of Textual Practice 23, no. 6 (pages 947–958), an essay which explores some of the issues that have been raised here. This is a collage of passages.

You are reading a poem and there it is, a torn strip of language peeling at one edge stuck on the surface of the poem like imitation wood paper in a Cubist painting. Seen from one inner perspective it merges with the aesthetic medium; from another it breaks out at right angles to the plane of the art. Once you start looking it is not difficult to find these strips of scientific language in the work of a number of poets. They radiate intransigence from many poems that J. H. Prynne published in the middle seventies, such as these four lines from “Pigment Depôt” in Wound Response: “We apply for rebate on the form provided / injected with vanillic acid diethylamide / our displacement is fused / by parody.” And here is a large strip in “Again in the Black Cloud”: “Damage makes perfect: / ‘reduced cerebral blood flow and oxygen utilisation / are manifested by an increase in slow frequency waves, / a decrease in alpha-wave activity, an increase in / beta-waves, the appearance of paroxysmal potentials.’” Mei-mei Berssenbrugge has increasingly written biologicals into her poems as in these three lines from the book Endocrinology: “What is physical light inside the body / A white cloth in a gold and marble tomb, to focus the expression of the tomb. / Shortly after phagocytosing material, leucocytes increase their oxygen consumption and chemically produce light.” Poets flypost the walls of poetry, moving from Cybernetics to particle physics, then recombinant DNA cloning and the autogenetic neologising of molecular biology: the call to the public goes on.

The articles and textbooks from where these strips have been torn are not usually identified, the source is not the point, the reliability is not the point, you either know or you don’t, and the poet isn’t teaching biochemistry for experimental victims. Scientific knowledge is always changing, constantly revised by new research, new experiments and new models of material reality. The plum pudding model of the atom gives way to the planetary model and that eventually disperses into even less easily visualised models of indeterminate energy states, decoherence and quarks for what William Burroughs would probably call the ‘marks.’ Genetic material turns out not to be made of proteins after all. Safe materials, mercury, asbestos, become homicidal.

We might have expected much more reference to science and technology than we actually find in poetry. Our bodies are reshaped by medical and recreational drugs, by innumerable pollutants in the manufactured substances around us and in the air, water and food we eat, food that had already been genetically modified by intensive breeding long before however careful we are as consumers. Our five senses upgrade to new processors and polyamides, boosted by increased electron flow. If we believe that social being precedes individual consciousness, then we must acknowledge that our senses of self are increasingly modified by the communication technologies we use to sustain our relations in work and in our personal lives. Surely this flowering of science and technology ought to be fully acknowledged in poetry. More amino acids, more fundamental particles, more language, alphabets of new objects and processes that continue to appear in our world like litter from an advanced civilization: Abaxial, Beringia, Contig, Deskewed, Epitopes, Ferrodoxin, Glycosylation, Homeotic, Inter-genome, Jejunum, Kinesin, Lensing, Metabolome, Nucleotide, Orthologue, Palaeointensity, Quantumteleportation, Remanence, Subtelomeric, Transposon, Urease, Vanilloid, Wnt, Younger Dryas, Zeolite.

The science strip worn by the poem is more disruptive of its workings than many other types of citation: popular culture, our dear departed literary lions, the landscapes of moor and peak, friends and names that drop with a splash of celebrity. The truth status of these scientific terms, facts, and knowledges is itself a complex production controlled by the institutions of science, and unpredictably changes depending on where (and when) it is situated. Its authoritative presentation requires for its warranted presentation a bona-fide scientist who is recognised by peers to have the understanding to affirm one of these facts. By the time that a poet cites such material it has been largely disconnected from the networks of legitimation on which the distributed production of knowledge in science depends. The strip of science language is inert and its significance attenuated. This attenuation results from the rapid half-life of scientific documents and the knowledge they present, or as scientists say, the citation lifetime of most natural science publication is brief, because scientific fact is always changing, and this means that almost any allusion to scientific knowledge is likely to be out of date within a few years. The strip in the poem may look much more faded than the rest of the language around it, like yellowing newspaper consumed by its acids that has been pasted onto a canvas that continues to be milky with white primer.

Marcella Durand: This discussion of the inarticulation of science, and of poetry, strikes at some certain core of the disjunct between the two fields, with that inarticulation extending beyond language to how exterior world is apprehended or not via all senses (thinking of, again, Mordecai-Mark Mac Low talking about how streams of outer-space mathematical data is best understood visually). So in that inarticulation, how does form begin? For me, the form of a scientifically based poem (and I agree with Peter that all of my poems are based in science, or ARE science, b/c, right, how can you extract yourself from that sea of science/technology/communication?) is a struggle — how do you find the shape about which is the poem within which is the science? I thought of this reading Amy’s poem, because she’s doing some radical reshaping to accommodate the “subject” of her poem (And Amy, could you maybe talk about that a bit more?), for instance, incorporating timelines as a way to convey (as in conveyor belt?) words along in non-linear progression (thus form works reverse to content, reminding me of Francis Ponge’s — hi Tina! — bird flying counter to the direction of the line).

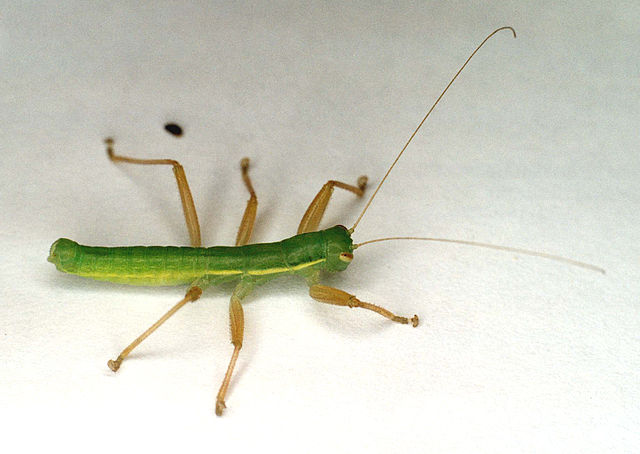

So thinking about form, and speaking of writing upon a subject of which one knows nothing, I was commissioned to write a poem in honor of L. L. Langstroth, “the Father of American Bee-Keeping,” who invented a hive with movable frames and who discovered “bee space.” I’d thus judge this poem have a scientific base, even though nineteenth century so, and maybe more industrial, but have been having trouble with the inarticulation falling between form and intent. So far, I’ve got an acrostic form, following LLLANGSTROTH, which has twelve letters, divided into couplets, to reflect the six-sided cells of bee combs, with a rhyme scheme going ab/cd/dc/ba/ab/cd. (I added the rhyme scheme b/c the poem is going to be read aloud, not by me, to all sorts of agricultural folks, including the Pennsylvania Secretary of Agriculture, so I wanted some sort of sonic doorway.) So, in a forced, awkward, public way, it’s going to be a confluence between poet/scientist or at least agriculturalist. I began writing directly about bees, but then suspected the bee-savvy audience would immediately find mistakes in my bee-knowledge (which is basically that they sting and make honey), so now I’ve veered off into the more comfortable territory of using language as a sort of investigative tool into this unknown pool of knowledge. Anyway, I’ll post it when it’s done, but here’s another poem about bugs, where I think content affected form (and I also got critiqued by an apparent “expert” for not pronouncing the Latin correctly during a reading):

“on a distant mesa, surrounded by desert”

walking stick and enclosed in amber mecoptera on isolated

mesa surrounded by desert phthiraptera barren what does it

live on small armored dermaptera half one thing and half

another orthoptera external hard encased siphonaptera listening

what distance stripped strepsiptera one wondering what it or

it could be one heteroptera wingless and vicious sweet mantodea

no name for one’s own listening neuroptera if each was

discovered a radio’s long wave lepidoptera the beetles and

the termites biting embioptera such visibility no major sources

of light pollution urban just eroded spire psire eir raphidioptera no

food source and no water ancient pine trees and resin rock slick

psocoptera found within itself others a ravishing trichoptera thrips

and book lice coleoptera small clouds and visible evaporation scent

megaloptera faults folded thrust ersion rosion sliding isoptera

dobsonflies and webspinners phasmatodea not one name and another

ephemeroptera dust devils invasive shrubs miles such armor homoptera

and what is one and another in mesa in mineral odonata silverfish and

jumping bristletails most are plant-eating hymenoptera inside one self

eroding salt intrusions slow flexing blattodea landscape one and visibility

another rock one you and not what one is, armored thysanoptera within

one self another you and rock in mesa surrounded no pollution ution

lusion pol polis plecoptera stoneflies, webspinners and mantids,

earwigs, angel wings, cicadas blattodea when one thinking they were

gone and in amber discovered one zoraptera the gladiator, armored

one who eats others, a carnivore, predator grylloblattodea but without

bt wtht to one without wtht a name no name unnamed diptera only

the name of others inside one armored the predator others zygentoma

archeaognatha on such mesa surrounded by miles long wave radios

listening for pollution, plltn, erosion, rsn, elision, pollus, erode, the

bug listening there on top of the mesa, encased and armored the exo-

skeleton, the fossil, ecout rsion, sliding the name the names

of others inside one and does it live the mantis-walkingstick

grasshopper predator, carnivore, waiting and ravishment such bare

sand, rock, slick, the mantosphasmatodea, gladiator, armored, going in.

Retallack: Dear Q-1ers,

Here is a second post stimulated by just having read all of yours.

Poetries in their many forms and hybridities, sciences in their many forms and hybridities are most importantly for me means of exploring the worlds in which I/we live. I come to an interest in science in two main ways: through being exposed to my electrical engineer father’s experiments and inventions (which I took — and still do — as a form of play) as a young child; and later, through my interest in philosophy of language, ethics, and science — all of which became interrelated in my explorations. Since I’ve been particularly interested in investigating otherness and the possibilities of being human in the state of grace I like to think of as “reciprocal alterity,” I think methods and models of science — along with the kinds of thought experiments beloved by philosophers — have informed a lot of my work as a poet. Maybe they are imaginative prosthetics of some sort (and in that way akin to metaphor) reaching toward alterity. Poetry, more than the sciences, allows for questions involving the positioning of human subjectivities to be an intimate part of all this. And so it all circles round to the primacy of the kinds of things one is trying to explore by means of language, but I don’t think it (the relation of science to poetry) all resolves into questions of vocabularies or discourses alone.

I think a lot has been said already about the way the scientific entries and interventions that are labeled metaphors (and Rae is right: all lang. including scientific is importantly metaphorical, in part) have been part of poetry for millennia. I don’t think it’s a problem at all that scientific findings (and thus the language in which they are framed) are constantly changing. The larger paradigms (conceptual frameworks) within which scientists work actually change relatively infrequently. (a tidily mechanistic world view was only supplanted by the very messy 2nd law of thermodynamics (entropy, etc.) in the nineteenth century; simplicity and elegance, by complexity and chaos in the twentieth century; Newtonian physics by relativity, quantum dynamics, incompleteness and uncertainty principles likewise in the twentieth. And any historian of science will tell you that all those “supplanted” paradigms are still in use in specifically designated ways as is Euclidean geometry. Still, in the purview of what shows up in the New York Times science section, what does or doesn’t count as a legitimate contribution to a given paradigm is subject to rapid changes and reversal. Not, however, the criteria by which the nature of the questions and what counts as evidence is determined.

The real question is — to put it crudely — So what if it turns out in the new cosmological physics that there really aren’t any black holes, leaving all those thousands (millions?) of poems with their black hole metaphors embarrassingly intact. Is this decade’s science true? … false? for a while, for all time? Is that really the key question? Universal and eternal truth value certainly isn’t. But the poethical question of what kinds of knowledge and understanding are necessary for the poet who feels a need to be an inquisitive, responsible part of her/his contemporary moment is key. Gertrude Stein — who was certainly interested in and influenced by the scientific developments of her era (at least as reported in the Herald Tribune) said that it’s the business of artists to be part of their contemporary world. If one agrees with this, as I do, it’s hard to imagine science in some form or another not informing what one is doing as a poet. The big question is of course the one that Rae, James, Evelyn, Peter, and Marcella have been addressing, How?

I’ll sketch some thoughts on that in another post. For now, I just want to say that what interests me in the way of a challenge even more than vocabularies, references, allusions, etc. (all of which can bring fascinating dimensions and perspectives to the poetics of a text) is how texts can literally (lettristically, for instance) enact the dynamic principles that a scientific model has been developed to understand. E.g., enacting rather than referring to our latest (scientific) definition of chaos — modeled as “pattern bounded indeterminacy.” Enactment means that the “dynamic of order and disorder” is actually happening in the language of the poem, is a moving principle. This can be on a lettristic, phonemic, syntactic, grammatical level, not merely a matter of bringing in some technical terms. I think some of Stein’s texts — in their syntactical dynamics — work this way and I’ve written about that, particularly in the essays on Stein in my book, The Poetical Wager. (I can post an excerpt, once I figure out how to do that!)

I think Amy’s “Borealis Time Signatures” may be working with the dynamics of scientific modeling rather than reference alone. I hope she’ll/you’ll say something about how you composed this work. (And, Marcella, I’m curious how you composed your poem as well.) There are many (though not enough perhaps) examples of this dynamical, literal incorporation of scientific understanding into textual composition that — insofar as it is a poetics of exploration — is taking that understanding into the realm of questions of subjectivities. (A few poets who come immediately to mind in relation to this kind of work are Tina, of course, Juliana Spahr, Jena Osman, and John Cayley with his digital poetics. But, this is not about creating word robots. (Though that could be an investigation of the “post human.”) It, again, always has to do with subjectivities gathered and dispersed among the complexities of our contemporary (further complication of history). I will attempt to post my lettristic infection, A I D /I/ S A P P E A R A N C E as an example of something I’ve done that sets viral dynamics in motion in the functioning alphabet of the poem.

Gilbert Adair: Marcella, the reading of this must’ve been a tour de force, the pronunciation carper notwithstanding. (As a final effort to get a mathematician to appreciate literature, a friend once convinced him to read merely the whole of Crime and Punishment. “So, what did you think?” “Well, in one passage Raskolnikov leaves the house at 8 pm and returns at 6 pm the same evening.” “Hmm — but apart from that?” “There was more?”)

Anyway, given that my interest in all this began in the question of whether or not one shld look up the meanings of scientific terms, my initial response to your piece was that here at least that wld be superfluous: it’s already doing a marvelous job of conveying the unimaginable profusion of insect life; we have only to sit back and be stunned — and enjoy, in my opinion, some very nice comedic effects: the siphonaptera are probably squirting soda into whiskies, the neuroptera are obviously highly strung, the homoptera are gay, etc. (Something like Rae’s recent and wonderful remark [in “Zukofsky”] re quantum physics, transferred to mini-life on earth: “We … come prepared for the bizarre. We’re pre-defeated and ready to enjoy our quandary. Maybe we’re too ready to embrace what we don’t get as some version of ‘mystery.’”) But then I thot, well, why not give it a try? And the poem at once became much more participatory.

There follows a version of the definitions, using dictionary.com and other web resources. I should note that the printing of the poem in Area (2008) italicizes the technical terms; the printing here [i.e. on the Google Group website] doesn’t because the site doesn’t allow it; but this I’m inclined to prefer.

| Mecoptera: |

an order of carnivorous insects usually with long membranous wings and long beaklike heads with chewing mouths at the tip. |

| Phthiraptera: |

wingless external parasites of birds and mammals, divided by some into biting lice (Mallophaga) and sucking lice (Anoplura). |

| Dermaptera: | earwigs and a few related forms. |

| Siphonaptera: |

fleas. |

| Strepsiptera: |

small insects with rudimentary anterior, and large and membranous posterior wings; parasitic in the larval state on bees, wasps, and the like. Also called Rhipiptera. |

| Heteroptera: |

“true bugs” |

| Mantodea: |

or mantises (talking of Zukofsky); an order of insects that contains approximately 2,200 species in nine families worldwide in temperate and tropical habitats. |

| Neuroptera: |

an order of insects having two pairs of large, membranous, net-veined wings. They feed upon other insects, and undergo a complete metamorphosis into, e.g., the ant-lion (hellgamite) and lacewing fly (told you: highly strung). |

| Lepidoptera: |

“insects with four scaly wings,” the classification that includes butterflies, moths, and skippers, coined 1735 by Linnaeus from Gk. lepis “(fish) scale” (related to lepein “to peel”) + pteron “wing, feather”; in the larval state, caterpillars. |

| Embioptera: |

lit. “lively wings,” a name that has not been considered particularly descriptive for the group. The common name “webspinner” comes from the insects’ ability to spin silk from structures on their front legs, which they use to make a web-like pouch or gallery in which they live. |

| Raphidioptera: |

a.k.a. snakeflies, consisting of about 210 extant species. Together with the Megaloptera they were formerly placed within the Neuroptera. Predatory both as adults and larvae, they can be quite common throughout temperate Europe and Asia, but in North America occur exclusively in the Rocky Mountains and westward, including the southwestern deserts. |

| Psocoptera: |

includes booklice and bark-lice. |

| Trichoptera: | or caddisfly; a variety of small, freshwater insects having two pairs of wings covered with hairs, and often hair on the head and thorax. |

| Coleoptera: |

“sheath-winged”; the term used by Aristotle in describing beetles. |

| Megaloptera: | alderflies; dobsonflies; snake flies. They dream of world domination. Sorry, I’m getting giddy here. |

| Isoptera: | lit. “same-winged”; the group of *eusocial insects commonly known as termites. *used for the highest level of social organization in a hierarchical classification. |

| Phasmatodea: |

stick insects; leaf insects (sometimes considered a suborder of Orthoptera). |

| Ephemeroptera: |

mayflies; see David Ives’s short cutesy play, Time Flies. |

| Homoptera: |

a large suborder of Hemiptera comprising cicadas, lantern flies, leafhoppers, spittlebugs, treehoppers, aphids, psyllas, whiteflies, and scale insects which have a small prothorax and sucking mouthparts in a jointed beak, and undergo (unlike heteroptera) incomplete metamorphosis. |

| Odonata: |

dragonflies and damselflies. |

| Hymenoptera: |

the order of insects that includes ants, wasps, bees, ichneumon flies, sawflies, gall wasps, and related forms, that often associate in large colonies with complex social organization, and have usually four membranous (“hymen” as we all know=membrane) wings and the abdomen borne on a slender pedicel (ultimate division of a common peduncle). |

| Blattodea: |

cockroaches; in some classifications considered an order. |

| Thysanoptera: |

the thrips (thysan: tassel or fringe). |

| Plecoptera: |

stoneflies (think helicopters). |

| Zoraptera: |

an order containing a single family, the Zorotypidae, which in turn contains one extant genus (Zorotypus) with 34 species, as well as 9 extinct species. |

| Grylloblattodea: |

insects combining “gryll” (cricket)- and “blatta” (cockroach)-like traits; with only 25 species described worldwide, the second smallest order of insects. |

| Diptera: |

“two-winged”; a large order of insects (housefly, tsetse fly, sandfly, mosquitoes, midges, and gnats) that have the anterior wings usually functional and the posterior wings reduced to small club-shaped structures functioning as sensory flight stabilizers; and a segmented larva often without a head. |

| Sygentoma Archaeognatha: |

did not match with any Web results. |

| Mantophasmatodea: |

an order of insect identified in 2002 in a 45-million-year-old piece of amber from the Baltic region. |

Retallack:

Archimedes’ New Light

Geometries of Excitable Species

Mortals are immortals and immortals mortals; the one

living the other’s death and dying the other’s life.

— Heraclitus

bodies cleave space of all the triangles in the prism :

one glimpse of cornered sky in all the triangles in the sphere :

fleeing over cardboard mountain with all the segments in the parabola :

grey morning blank aluminum all the parabolas in the sphere :

their own cold love song breached all the circles of the sphere :

abrupt start of rain all the vertices of the prism :

clacking sticks

night barks

window blank

Reason is a daemon in its own right.

another song whose bird I do not know

.the.center.of.gravity.of.the.two.circles.combined.

around them in us we were very they

what comes to mind in this five second cove

.whose.diameters.are.and.when.their.position.is.

.changed.hence.will.in.its.present.position.be.

lacking usage equal to the noun she chose

.in.equilibrium.at.the.point.when.all.the.angles.

all different before he heft laughed defiled gravity lost again

.in.the.triangles.in.the.prism.all.the.triangles.in.the.cylinder.

interior angles exposed collapsed into each each

.section.and.the.prism.consists.of.the.triangles.in.

the terrible demonstration of fluid dynamics beginning again

.the.prism.hence.prism.hence.also.the.prism.and.the.

areas of distortion the burning vector fields

more mathematics of the unexpected:

the total curvature of all spheres

is exactly the same regardless of radius

Lacking experience equal to the adjective she chose

scratch abstract sky shape

hoping for more

.whole.prism.containing.four.times.the.size.of.the.

.other.prism.then.this.plane.will.cut.off.a.prism.from.

struggle to flee her altered nativity

repeat story of stilt accident

no the drama has not abated

.the.whole.prism.to.circumscribe.another.composed.

.of.prisms.so.that.the.circumscribed.figure.exceeds.

exhausted boy soldier reads book numb

rag head taken by stiff light

fig one triumph of the we’re

.the.inscribed.less.more.than.any.given.magnitude.

.but.it.has.been.shown.that.the.prism.cut.off.by.the.

empty listen ridge cold whistle

unison whipped wide awake

box of spook salt

.inclined.prism.the.plane.the.body.inscribed.now.in.

.the.cylinder-section.now.the.prism.cut.off.by.the.

not a coast but a horizon not a coast

blank seas soak grain senses demented

sense of thigh once now not yet juked

may deter may bruise

bequeath before death

green countdown bluebook

she said now that she thought about it

she thought it must have had something

to do with that feeling of self possession in

the moment after the apostrophe took hold

One’s .inclined.plane.the.body.inscribed.in.the.cylinder.

a stock image

a rhetorical device

a dubious gesture

an obsolete hope

One’s .section.the.parallelograms.which.are.inscribed.in.

quadrant spoke motion

a prod to come to life

meddlesome meaning meaning tangent

One’s .the.segment.bounded.by.the.parabola.but.this.is.

sordid alignment of slippery parts

please hold that place stretch the we

jelly throat made good hold that note

One’s .impossible.and.all.prisms.in.the.prism.cut.off.by.the.

no such five illusions

no vowel exit mutters fruit

my no flute war

torque valley breath

gun cold air cont’d

night barks windows blank

grey morning’s blank aluminum

its own long cold burst that kills

a look cornered sky

One’s .inclined.plane.all.prisms.in.the.figure.described.

geometry of the tragic spectrum

eye caught in grid

this thought empties itself in false déjà vu

the echo seen but not heard

the absence of x had been distracting all along

Rationalism born of terror turns to ecstasy

.around.the.cylinder.section.all.parallelograms.in.the.

.parallelograms.all.parallelograms.in.the.figure.

.which.is.described.around.the.segment.bounded.

.by.the.parabola.and.the.straight.line.the.prism.cut.

.off.by.the.inclined.plane.the.figure.described.around.

.the.cylinder.section.the.parallelogram.the.figure.

.bounded.by.the.parabola.and.the.straight.line.

.the.prism.the.prism.cut.off.by.the.inclined.plane.

Note: This poem includes language from Geometrical Solutions Derived From Mechanics: A Treatise of Archimedes, Recently Discovered And Translated From The Greek By Dr. J. L. Heiberg, Professor of Classical Philology At The University of Copenhagen. La Salle, Illinois: The Open Court Publishing Company, 1942 (Copyright 1909).

Aurora Borealis as seen from the International Space Station, 2005 (image courtesy of NASA).

Catanzano: I began my borealis project by gathering books from my library, focusing exclusively on those that had profound impacts on me and letting go of those I felt I should be including for xyz or which were close but no cigar. That alone was a significant exercise, because it made me examine what I was using for criteria. I was pleased that I had twenty-three books by the time I was done, as that is a useful number for me in my numerology pantheon that sometimes rears its mane in my poetry.

Then I created the cipher for the borealis, the twenty-three writers, by selecting a word that emblematically represented that writer in my imagination. There is also the tesseract, which developed because I felt one writer needed a concept rather than a word. I ordered the borealis in a linear, Newtonian manner, so that the first ciphered writer is the first writer that captured my imagination, and the last ciphered writer is the most recent writer that captured me, though that writer lived in the nineteenth century. But I only recently felt captured by her. In the two relativity time signatures (special and general) that I included in my selection, I placed the ciphered writer after each word that related best to that writer in my imagination.

This was the experiment in those time signatures: how does Alfred Jarry and my cipher of him, “present” (as in his “imaginary present,” which I see as playing on a seesaw with Stein’s “continuous present”), relate to the time signatures, which are exploring special relativity and general relativity? I placed him next to the word, “time,” because his phrase “the imaginary present” comes from his essay “How to Build a Time Machine.” I’ve always thought of poems as time machines and his writing in particular as redefining time. Jarry is also “deciphered” in my sidereal time signature, since he is like a distant star for me, the space in spacetime. That depiction of Jarry becomes the “constant” in which the rest of the borealis — “the observers” in the relativity thought experiments — are either moving from or toward, depending on whether it’s special relativity or general relativity. In my planck time signature, not included in the selection I shared, I decipher Walt Whitman by creating a fractal pattern with his name that I generated by just copying and pasting his name on a page to create an image … a simple process that made an interesting pattern, one that happens to have the words “hi” and “Walt” center stage. I ended up loving that, because it looks like the poem is saying hi to Walt Whitman, so it’s a little funny and slightly sentient. I also made a Newtonian timeline that had phrases from my borealis, but since it is easy to decipher, I decided to scrap it and make the algorithmic and hyperdimensional timelines instead, distilling and then rearranging words from the writers.

On a conceptual level I am interested in what Rae said, how my subjective poetic lineage can interact with theories of time and how poems interact with spacetime, on the page, in physical reality, and in consciousness. The final time signature — also not included in the selection I shared — is my deciphered borealis that takes the visual form of a spine. But I want to complicate its deciphering by writing it in invisible ink. I got that idea from the person I am seeing who wrote a book that has a page written in lemon juice, which is a natural invisible ink. He handmade each book, so maybe I’ll have to do that, too. But this borealis project is just a twenty-page section within a manuscript of other projects, so I don’t know how feasible it would be to make the whole thing myself. I’m trying not to worry about production as I don’t want to self-censor myself just because there might be challenges. I also plan on having a statement about the idea and composition of the project in the book, as I feel the concept, process and procedure are as important and maybe more important than the poems, or at least indistinguishable. I could use this convoluted explanation as a starting point! Anyway, I don’t mean to be so self-centered here. I’m looking forward to responding to the ideas everyone is bringing up. But since Marcella and Joan asked me about my project’s form and composition, I used this response as an opportunity to think through it more. So thanks!

Gilbert [to Joan]:

One’s .impossible.and.all.prisms.in.the.prism.cut.off.by.the.

“Archimedes’ New Light”

He is unworthy of the name of man who is ignorant of the fact that the diagonal of a square is incommensurable with its side.

Plato

A prism, that in optics means a transparent solid, often with triangular bases, used to disperse light into a spectrum, means in Euclid (midway in time between Plato & Archimedes) “a solid having bases or ends that are parallel, congruent polygons and sides that are parallelograms” (dictionary.com). Parallelograms have 4 sides, polygons indeterminately more than 2; a prism is therefore a mix of the symmetrical & asymmetrical — as are most strikingly both the visual design of your poem’s p 3 and its last line, “green countdown bluebook,” where color calls to color bracketing “countdown” but “countdown” at the same time takes its compound-word place with “bluebook,” & the nicely intricate patterning seems to make meaning imminent —

Which is perhaps where to note that the poem’s p 2, beginning “another song whose bird I do not know / .the.center.of.gravity.of.the.two.circles.combined.,” has caused me an interesting disquiet. All its lines are of normative syntax, but unpunctuated lines pretty much (but not entirely) alternate w/ ones every one of whose words is hedged by periods. This sets up a music so jangled & insistent, with possible irregular variations, as to overwhelm incipient comprehension of what waves to us in passing as being of definite & underwritten meaning, bye! Now that is hardly uncommon in the experience of linguistically innovative poetry. But here the anxiety niggled. How might this relate to what has haunted me since early in this project, John’s proposition (see “Science-Informed Readings”) that the identity scientific discourse is generally assumed to claim to share with objective reality, & the consequent authority of pretended affectlessness, “implies a powerful system of affect.” To say that this affect wld broadly differ depending on whether you are w/in or w/out a scientific discipline is to risk proposing a “2-cultures” scenario. But I want to know where we can here go with it —

In Hermes: Literature, Science, Philosophy, a 1983 translation of writings by Michel Serres, a number of pieces address the origin of geometry, given as the passage “from one language to another, from one type of writing to another, from the language reputed to be natural and its alphabetic notation to the rigorous and systematic language of numbers, measures, axioms, and formal arguments” (125). In fact, philosophy & mathematics share the requirement to exclude noise, which already gives them some common ground. Something else in common: both evoke & perform operations on abstract forms thro’ symbols whose accidental variations of graphology, of expression, etc., can largely be dismissed. The elimination or disregard of noise is thus “the condition of the apprehension of the abstract form” (68). Here then is a 1st accounting for my reaction to p 2: its jangled & insistent music threatens to drown out, makes no more than disquietingly noticeable, multiple verbal signs of abstract mathematical rigor — precisely that which by its very definition shouldn’t admit such distraction.

Equipped with that, I return to your poem. Already it was clear that it sets in interplay the abstract & the sensual, the transient & the eternal. The page design, & not inappropriately, evokes Williams’s Kora, Spicer’s “Homage to Creeley / Explanatory Notes,” & your own Afterrimages: fact & comment, substance & gloss, extension & condensation, syntactic-semantic clashes if not opacities & some promised/teasing illumination — hang on, I’m replacing present instance by past models; the former multi-replicates the dualism it designedly largely models (with variations) page by page, in each page’s dualism’s units. I seem to get as plausible “all the parabolas in the sphere” (from p 1) until I get to “all the circles of the sphere.” Could those even be counted? & hang on again: what is a circle’s “center of gravity” (p 2) anyway? Or: before I can notice these lines in this way, I have to have (re)learned from Serres that the origin of geometry in Greece had much to do with a famous crisis in mathematics caused by the advent of irrational numbers (“relearned”? — I had totally forgotten). An irrational number is one that within the given system, can’t be stabilized, whether because its position in a problem makes possible two incommensurable values for it, or because, like pi, it can’t stop proliferating. But where in arithmetic pi is a conceptual threat, in geometry it is a condition of being. The crisis of Pythagorean arithmetic (the beans having been spilled, according to Euclid, by one Theaetetus) was solved by the geometrical theorem ascribed to Pythagoras, working happily with irrational numbers. The cover-up, the durable triumph of (eventually) Euclidean geometry, requires a sacrifice or assassinations.

Seriously now back to your poem & its interplay of the abstract (rational abstract & irrational abstract) & the sensual, where “bodies cleave space of all the triangles in the prism” & the poem becomes a model of the human located within a field of abstract, regulatory calculations, trapped & shaped by them, yet there’s no point-for-point touching: crossings indeed from one language to another. The poem’s source text seems to be something else I hadn’t been aware of, a thirteenth-century text known as the Archimedes Palimpsest, 1st translated into English in the early twentieth century & now available online in digital form. Here, among other things, Archimedes apparently reveals his method for calculating unknown areas & volumes by reference to corresponding figures. Now the poem’s p 2 indeed ends with a glimpse of the possibility of measurement of certain figures whose symmetry holds across different scales: “more mathematics of the unexpected: / the total curvature of all spheres / is exactly the same regardless of radius.” Before that, however, the apparently largely dispassionate lines (whether the words are between periods or not) seem to me on rereading to afford another glimpse, here of a suicide: “all different before he heft laughed defiled gravity lost again”; at any rate, once this interpretation takes shape, the remaining lines seem to confirm some kind of defensestration or roof-jump, activating a certain logic of geometric relations in the space of gravity (a very Newtonian death) & entry into “areas of [corporeal?] distortion the burning vector fields.” After that, the poem only grows darker. On the right side of p 3, sets gone wild in terms of what contains what; on the left, lines that are increasingly & tantalizingly emotive: most clearly, the boy soldier is presented as a technologically erased casualty of our collective will (“fig one triumph of the we’re”) in, presumably, Afghanistan (“rag head taken by stiff light”) — in, precisely, a war about which very few of ‘us’ give a fig or find even remotely rational. The last line of p 4, given as the 1st epigraph to this response, precedes the drawn horizontal line, there’s no coda, & not least because of that, makes the page abruptly seem remorseless; “the” is power’s endlessly reiterated decree of its own rationality, say what you or anyone else might: indeed many are killed to sustain a claim to systemic logic in public discourse, & indeed, almost everyone knows better. This effect seems confirmed by p 5, which likewise lacks a coda — an x, even a teasing resolution (as in Williams, Spicer, etc.): “this thought empties itself in false déjà vu / the echo seen but not heard / the absence of an x had been distracting all along.”

The last page brings its title, “Rationalism born of terror turns to ecstasy,” together with the coda from p 1, “Reason is a daemon in its own right”; the cold little poem that goes with this, exclusively focused on geometrical terms & relations, seems now to indict the irrationality raging in a techno-war whose perpetrators feel their own lack of convincing motive or shaping scenario. It’s as if, thro’ your patient formal manipulation of materials that initially don’t seem too promising, the “affect” of purportedly affectless discourse to which John pointed — an affect that I suppose often has much to do with the masochistic pleasures of being excluded by the sternly inhuman but ingeniously & importantly effective — dissolves, just melts away, to reveal something not only routinely invisible but also normally inaccessible thro’ such vocabulary, & for which the poem sits somewhere between synecdoche & analogy: the terrifying non-face of technologically rationalized aggressive operations, in conformity with calculable laws of physics which are obviously of much wider (even universal) application.

Mantophasma zephyra, © 2002 P.E. Bragg.

Durand: Gilbert — I’m floored! And feeling that your effort demands a sort of sequel. The term “eusocial” alone … and Siphonaptera for fleas (applies also to mosquitoes and bedbugs I’d say). So would the Mantophasmatodea then be the smallest order of insect? (After the Grylloblattodea, which I’ll reveal here was my favorite moniker out of an obviously competitive field.) I’m happily perplexed by the Sygentoma Archaeognatha imposter, which seems a little too fantastic for me to have made up. Disturbing as well the “complete metamorphosis” of the heteroptera and the “incomplete metamorphosis” of the homoptera (and are the non heteros then “false” bugs?). Once again, can we call objectivity into question, please? The quote from Rae is very appropriate — I did indeed arrive at this poem pre-defeated and very ready to enjoy the quandary of it. I would say that’s generally *my* state in writing poetry from science.

I do have to also apologize for being offline. I was away for two weeks, and by away, I mean I was away from Internet, TV, and cell phone. I will catch up on all the very meaty responses in the next week. However, while being away, I found a book on the Museum of Jurassic Technology and was wondering what other people’s opinions were on it. I visited fully expecting to love it, but instead was left uneasy at what seemed an uncomfortable art-science relationship/creation, perhaps overly contextual or self-commenting or predigested, so much as not to leave room for much more creative generation? Wonder if this is cautionary?

Tina Darragh:

“Metaphor-Mongers and the Nuclear Snowcone”

On October 20, 1999, then-Secretary of Energy Bill Richardson proclaimed that 1,000 acres within the Los Alamos National Laboratory would be designated a wildlife preserve, “an able bearer of New Mexico’s legacy of enchantment.” As part of a DOE project designed to give the agency an environmentally friendly image, buffer zones around nuclear sites were promoted for their “biodiversity” rather than for their “nuclear toxicity.” Perhaps Richardson was thinking of Emerson’s “the whole of nature is a metaphor of the human mind” when he transformed “pollution” to “preservation.”

parables

perfectly intact

something regarded

the great joy

as a stand-alone

insights

gather images

mountains, earthquakes

layers to another

scientific minute

or minute circumstance

a word from the proper

taken for a hard

wrap up

_______

Crackerneck Wildlife Management Area and Ecological Reserve: radioactive alligators and bass

Sagebrush Steppe Ecosystem Reserve: big-eared bats carry radionuclides to nearby territories

Hanford Reach National Monument: Russian thistle flowers break off to become radioactive tumbleweed

_______

Mutations are not metaphors, but they’re very good guides.

“Exposure” now a combination of “undefined dose” and “brought to light.”

Green “pass through” shift Deeper thirled.

________

Whenever it would snow, my mother would make us snowcones with cherry syrup. It made her happy to take something that was natural and turn it into a treat. Then one snowy day Mom was crying instead of laughing. She’d read an article that said there was nuclear fallout in snow, and children shouldn’t play in it let alone EAT it. She was sure that we were all going to die. But we just became mutants, like everyone else.

________

metaphor: circulation in the production of norms

mutation: an instance of change

mutation metaphor: circulating change is the norm

_______

I’m a nuclear mutant and I’m proud

to core a metaphoric shroud

revealing who profits from the cloud

over history — let’s sing aloud

“we can’t be owned when we’re the crowd”

Tina Darragh

notes:

On October 20, 1999 …

Joseph Masco, “Mutant Ecologies: Radioactive Life in Post-Cold War New Mexico,” Cultural Anthropology 19, no. 4 (November 2004): 517–550. A BIG THANKS to Diane Ward for sending me this article.

metaphor: circulation in the production of norms …

Isabelle Stengers, The Invention of Modern Science (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000).

Adair [to Amy]:

It is worth noting that the Machine has two Pasts: the past anterior to our own present, what we might call the real past; and the past created by the Machine when it returns to our Present and which is in effect the reversibility of the Future.

Likewise, since the Machine can reach the real Past only after having passed through the Future, it must go through a point symmetrical to our Present, a dead center between future and past, and which can be designated precisely as the Imaginary Present.

… Without the Machine an observer sees less than half of the true extent of Time, much as men used to regard the Earth as flat. — Jarry, “How to Build a Time Machine” (1899)

A premise of Jarry’s essay is that time is already all there, that it simultaneously & forever flows, & that while we are where we momentarily are in it, it can be visited at any point if we are inside a machine that isolates us from, even as it makes us virtually porous to time’s flow, allowing that “to pass through us without modifying or displacing us.” Comparably the poem in “Files” that constitutes the “Working Notes” for your borealis project seems to me a delightful & tough-minded love poem putting the “jewel” of spatial durability (associated by proximity with an increasingly polarized public domain, “its sides evolv[ing] feral”) in interplay with the “rainbow” of temporal passage — a demand we all at some point make for amorous permanence, in interplay with the experience of love changing in time; while the tesseract, the 4D spacetime cube, is the figure charged with uniting these aspects —

In the poems for your project extracted for this forum, that — as we learn from your supplementary comments — are (otherwise relatively covertly) “heartshaped,” pervaded by affections for a range of writers/works, “jarry” is the only name appearing in the text (three times), in a spatial arrangement of letters that may evoke a constellation moving clockwise. In other words, the project presents itself as composed almost purely of ciphers, the personal aspect of the generative of it almost as invisible as any personal in a science project —

In this your work differs, but perhaps only trivially so, from Jarry’s “science of imaginary solutions, which symbolically attributes the properties of objects, described by their virtuality, to their lineaments.” It’s worth comparing methods here. Jarry moves with immediate logic from the three physical requirements of a time machine — first among them that it be at once “absolutely rigid” and “absolutely elastic” — to a partial model in the “luminiferous ether,” thence to a meeting of all requirements in an arrangement of three gyroscopes. Yes indeed. Familiar analogies help soften us to outrageous propositions: “the stationary spectator of a panorama,” after all, “has the illusion of a swift voyage through a series of landscapes”; why can’t we, then, be traversed by time “as a projectile passes through an empty window frame without damaging it, or as ice re-forms after being cut by a wire, or as an organism shows no lesion after being punctured by a sterile needle.” The delight is in the thoroughness & panache with which he pulls it off; the element of rule-bound game in trying to spot the cracks in a text that couples an inbuilt tongue in cheek with an invitation to critical thot (the “luminiferous ether” was jettisoned by Einstein in 1905, two years before Jarry’s death, but physicists still have fun speculating on the possibilities of time travel) —

Your poems aren’t traveling in time considered as a linear flow but rather in post-Einsteinian spacetime. The methods, at least in the extract posted, involve geometrical & syntactic/semantic variations on an initial list of words — variations that in page by page including feeds for the page that follows, eventually leave the initial list behind. The poems establish conventions to realize what may be hypothesized but could never be seen; Duncan’s remark in his Preface/Introduction to Bending the Bow (1968) — actually in reference to Olson’s (another poet for whom spatial layout was key) “Letter, May 2, 1959” — that “the boundary lines [paced off] in the poem belong in the poem and not to the town,” could be applied to your texts & Jarry’s essay alike —

The words as arranged in the initial list come across as (often) concrete & visualizable yet vulnerable in the work their arrangement is requiring them to do, even out of their depth: straining to cross the conceptual & dimensional gaps lodged in their single-space separations (“continuous / worlds / present / skin / distantly / mirrored …”); the tesseract figure coming between “eyeholes” & “demur.” On the page meanwhile, the shape indicates a simultaneity, some kind of body (not necessarily human) standing there in defiance of time. Following this, scientific concepts seem to provide the prods for geometrical-syntactic-semantic gambits. In “SPECIAL RELATIVISTIC TIME DILATION: AN EXPERIMENT IN RECIPROCITY,” the list doubles & faces off, with wider spaces between the letters, making the words prominently elements of design; the arrows drawn between & either side of the lists evoke, again but differently, both a 2D surface & two-way coilings in spacetime; in the prose passage below, the list-words are jumbled & variably repeated, the vertical order in which they have thrice appeared now distributed to play sometimes mildly comic, sometimes dimensionally lurching interference thro’ what seems mainly a directly quoted passage from a physics textbook (“In special relativistic time dilation, based on Einstein’s theory of special relativity, each observer moving away from a nearby gravitational mass perceives the other as moving slower; as such, the time dilation effect is reciprocal,” etc.) — until the last sentence. In fact, the last 2 sentences are worth parsing into their components & quoting separately:

calibrated / amplitude / distantly / air / happening / air / skin / urge / exactly

Counterintuitively this [that what is at stake are different relatively velocities] presumes the relative motion of both observers is uniform; the observers do not accelerate with respect to one another during their observations. Click my symbol for your equation.

Huh?! Even as “the heartless voids and immensities” (Melville, “The Whiteness of the Whale”) — & intangibilities — “of the universe” prompt a need for intimate connection, we shift from a textbook not only to internet (granted, the bulk of the para cld have come from some wikipedia article) but to some unexpected salesperson’s oily assurance of instant gratification. & the tesseract becomes established not as what the words are modeling but as the mathematical figure necessarily posited to connect them while they model other things.

Now we can move relatively quickly (“Pun intended,” as President Obama quickly told Jon Stewart following his “heckuva job” Summers/Brown gaffe). Shifting to general relativity, the next page posits intimacy of connection, physical as well as emotional/imaginative, at both human & cosmic levels. After that, the “logarithmic” timeline — logarithms the exponents of powers in tables I cld manipulate at school with invariable success but never understand — disperses the list-words ever more thinly in making it to the “feral” political world glimpsed at the beginning of the “Working Notes” (in the schema below, “—” = “new”):

skin / — / tear

— / words / mirrored

— / — [one-off feed for next page] / — [primary feed for next page]

— / [tesseract figure] / —

— / — / words

— / — / air [2ndary feed for next page]

— / — / —

— / — / —

Common to both cosmic & political dimensions of the poem, on the dubious assumption they can be so cleanly separated, is a familiar avant-garde/linguistically-innovative-poetic tenet memorably articulated by Allen Fisher in “Banda,” the first of the Gravity poems: “The quantum leap / between some lines / so wide / it hurts.” The last borealis page posted initially hints at, then, it seems to me, confirms its geometric model as one of asymptotes, lines which forever converge but never meet, & key destabilizers of Euclidean geometry once they were posited in the Russian/Hungarian 1820s (Jarry mentions one of the mathematicians involved, Nikolai Lobatschewsky, in whipping thro’ various accounts of what space might be). “Imaginary Present,” okay.

Ongoing relations between 'poetry' and 'science'

Edited by Gilbert Adair