Zukofsky

Is there anything you want to say about poem 12 from Anew?

Adair: I’ve just re-listened to the PoemTalk program #22 that started this off, and was struck by the prominence of references to quantum physics and relativity as informing what Charles calls “the doubleness of different things” that is pervasive in the poem. I should make clear why — directly related to that — I think it’s worth looking up the meanings of the scientific term “condenser,” which my Collins dictionary at the time informed me had the following meanings:

1. an apparatus for reducing gases to liquid or solid form by abstracting (removing) heat, as in refrigerator unit;

2. a lens for concentrating light into a small area;

3. a device for accumulating an electric charge via two conducting surfaces separated by a dialectric (a nonconducting substance or insulator).

So here are devices functioning at our own molecular level, visible with the naked eye, which resonate in multiple ways with themes of the poem: gas/liquid transformations, focal perception, things that conduct force but wear down (a glimpse of entropy, which in 1944 Zukofsky could parallel with the unusable depths of the ocean floor). But I should also stress that these are definitions I can seem to understand as long as the conversation would not stray too far outside them — at which point I’d be found lacking in some basic points of knowledge.

I think that for many of us, the same could be said for quantum physics and special and general relativity; and that this poem could usefully be thot of in terms of knowledge we seem to have (inc re relativity and q.m.), that sufficiently buoys us up in limited areas. Zukofsky himself allows that as the theories become more difficult to fathom, he at once sees a plurality of things “Or nothing” — or perhaps and nothing. If he is trying to locate himself and his family in the unseeable massiveness of modern America, that is certainly relevant. I would suggest, then, that twentieth-century physics gives him a way, based in what he and we take to be reality — not religion, not anything inviting a mystical response — to be true to his own cultural experience, but that it also fascinates him in and of itself; to be able to explore what is both invisible and substantially pervasive, even as one discovers everywhere post-Newtonian metamorphoses, without straying into mysticism (or worse, the mystificatory), is in my opinion, a valuable thing.

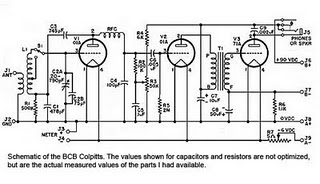

Middleton: Although I hadn’t had time to respond to the discussion here about Louis Zukofsky’s poem, nor to listen to the talk that sparked this off, I thought I knew where I stood. It did make sense to look up the meaning of the word condenser if you were not aware of its various scientific usages especially as an earlier term for capacitor, one of the staples of almost any electronic circuit, but the poem quickly moved past issues of definition. And it probably made as much sense to have in mind the condenser homonymically almost present in Pound’s aphorism “dichten = condensare,” or the line describing the poet’s workshop as a “condensery” written by Lorine Niedecker, a close friend and correspondent of Zukofsky, as the dictionary definitions. But then as chance would have it I picked up a book published in 1940, Why Smash Atoms? by A. K. Solomon (and later reprinted in Pelican) from a charity bookstall in what remains of the cloister at Winchester Cathedral, and realized that there is a whole chapter on condensers and their crucial role in the development of “atom smashers.” We are told endearingly that “a simple glass fruit-jar coated on the bottom and halfway up the inside and out with tinfoil makes a serviceable Leyden jar, a condenser,” as if we might be considering our kitchen table cyclotron. And reading the chapter I grasped that condensers were exciting things back in the early 1940s when Zukofsky composed his poem, and that the small condensers that smooth electric currents and act as gateways in radio and amplifier circuits to pass alternating currents and stop direct currents, are distant relations to the large condensers that step up voltages across their spark gaps to create the two million volt discharges used to study nuclei. These large condensers apparently created laboratory environments that looked “like a Hollywood director’s idea of the world of tomorrow.” I don’t know if Zukofsky read this particular book (it’s more likely he read Rutherford’s The Newer Alchemy), but finding it, and reading it alongside Zukofsky re-emphasised for me the importance of understanding the changing history of sciences that have influenced poets. So I think we do need (someone) to look up condenser, not only in a dictionary, but also in the sciences of his time.

I had also previously written a couple of paragraphs on Zukofsky’s poem for my book on science and poetry. It’s a poem that I love for its unusual combination of scrupulous attention to an accurate rendition of the complexities of physics, and avoidance of simply appropriating the metaphors for one’s own expressive purposes, with a willingness to admit to one’s own limitations that include the tendency to substitute easier images for the obscurities, and to be tempted into other sorts of physics envy. This is some of what I wrote. (It seems inadequate in the face of the waves of certainty and uncertainty in the poem, and I haven’t tried to mitigate the expository tone. Apologies!)

Zukofsky’s theme in this brilliant poem is the experience of trying hard to learn more about the new physics and its wave/particle hypothesis, and realizing that this science demands a continual relearning of what you thought you had understood. In the first part of the poem he adopts the tone of a patient expositor speaking from a position of knowledge. As someone familiar with electronics and the workings of capacitors or condensers, a writer of technical manuals, he feels confident at first that he can extrapolate his understanding of the new science of wave/particle fields. So he takes an image familiar to everyone, the wave motion of the sea, and links it to the more technical but still reasonably familiar idea of the condenser that works with the wave motions of electrons. How strange that light can have waves like the sea and yet can also be studied as material particles, invisible motes. Then he reflects on what it is like to engage with this science by comparing the awkwardness of the poet and nonscientist to the difficulty anyone encounters when gathering the blossoms of a tiny weed that falls off the stem as you try and pick it. The poem’s clever use of such traditional poetic metaphors in this new context underlines the sense of strain involved in trying to understand quantum mechanics. Zukofsky’s poem addresses the problem that Daniel Tiffany calls “the crisis of the equation of materialism and realism” made acute by the new physics: “as long as quantum mechanics failed to provide pictures of an invisible material world, it failed to constitute a new reality.” (Toy Medium, 268) Atoms were difficult enough to visualize; quantum effects resist modeling altogether. In the final lines of the poem Zukofsky folds the poem back on its author, the poet attempting not to be surprised into ignorance by the dilemma of a theory about the supersensible that exceeds the capacity of even the skill of poetry to find a cognitive diagram. The new science reduces him to the wonderment of a child when he realizes that there is “nothing” to see, a feeling of helplessness compounded by the need to keep learning afresh because the rapid growth of scientific knowledge constantly overturns previous facts and certainties. Knowledge of this kind appears to offer no more than a speculative “perhaps.” For Zukofsky, sciences like the new physics challenge the poet because they can carelessly undermine the bonds between sensory experience and understanding. One task for poets is therefore to rethink poetry’s relation to knowledge.

Armantrout: I wonder, was Zukofsky one of the first poets to struggle to understand the quantum world using images? I’m moved by the poem’s earnestness and modesty, the way he tries very sincerely to understand — and then recognizes defeat. It’s natural that he tries to conceive of what he’s reading about quantum mechanics in terms of what he already knows about science, about waves, about electricity, etc. But can an electric charge or “stress” be “worn down” like a common physical object? In lines 25–34 he stops trying to understand the new physics in the terms of whatever science he’s learned previously, and he moves farther afield to the image of the weed with its many, tiny seeds, impossible to count, easily “shed to the touch.” This is an image of the quantum (I suppose) before which he surrenders. The rest of the poem is about realizing that he’s faced with something he can’t grasp. That experience feels strange to him.

Armantrout: I wonder, was Zukofsky one of the first poets to struggle to understand the quantum world using images? I’m moved by the poem’s earnestness and modesty, the way he tries very sincerely to understand — and then recognizes defeat. It’s natural that he tries to conceive of what he’s reading about quantum mechanics in terms of what he already knows about science, about waves, about electricity, etc. But can an electric charge or “stress” be “worn down” like a common physical object? In lines 25–34 he stops trying to understand the new physics in the terms of whatever science he’s learned previously, and he moves farther afield to the image of the weed with its many, tiny seeds, impossible to count, easily “shed to the touch.” This is an image of the quantum (I suppose) before which he surrenders. The rest of the poem is about realizing that he’s faced with something he can’t grasp. That experience feels strange to him.

We, on the other hand, come prepared for the bizarre. We’re pre-defeated and ready to enjoy our quandary. Maybe we’re too ready to embrace what we don’t get as some version of “mystery.” As for me, I really do try to follow the latest version of string theory, say, but I know that bafflement is waiting around the next corner. When I write poetry in response to my bafflement which I do, I will sometimes turn to the absurd at that point, or the ludic, let the poem take a pratfall, make myself the butt of a cosmic joke, if that’s how it’s got to be.

Harvey: Looking up and trying to understand the science in Anew 12, although not needed to a great depth for a basic understanding of the poem, can play a part in the experiencing of the poem. The waves, particles and condensers etc. are held together by the language with enough flexibility for more detailed understanding of the parts to be acknowledged, and the poem still work/conduct/cohere.

But there comes a point, implied with the delicacy of the flowers on one stalk metaphor, where a limit is being reached, all this might be lost. This might be a limit of the following: of the reader’s understanding, experiencing the poem and trying to understand the science; of Zukofsky’s recall and personal understanding at the time of writing; of scientists’ understanding so far; of the tractability of the science, that can’t be put into words, or all these at once.

And these can also paradoxically be acknowledged by this poem.

The fragile flowers on one stalk metaphor brings to mind dendritic growth. The plant growing hitting a point in its own structure and the outside environment where its symmetry is broken, but if it carries on growing becomes a more complicated structure.

The mind of the artist and the scientist come together at this point: with how far do they understand the system they are looking at at one time? Do they understand what they are looking at well enough to move the parts around in respect to each other, their symmetry, well enough to form a model that includes all the parts that will stay in the mind long enough to be recorded? How much can they lose, or want to lose, and the system, however loose or limited, still cohere?

To reiterate what I wrote in my earlier response to question one, by quoting Eric Mottram — and I have had to reconsider much taking part in this forum which I thank everyone for — that scientists do more than measure they also design.

Catanzano: Gilbert asked me to discuss the tesseract image in my borealis, and I will, but first:

Rae’s earlier comments about the turn in Zukofsky’s poem, when the discussion of the science dissolves through the image of the innumerable seeds of the weed — when the unfamiliar experience isn’t understood — Rae points out our acceptance of bafflement and how this can turn her toward the absurd. I think about Alfred Jarry, as I often do!, and how his exposition of absurdity branches the fantastical to the point that I no longer expect bafflement but ease into “learning” his language of infinite combinations, which changes my relationship to the unknown, in the poem and in life, because I am no longer measuring what I don’t understand against the flower’s hard stem. The innumerable seeds introduce a novel approach to understanding that can’t be, like the child at the end of Zukofsky’s poem, stared at by ordinary means. Absurdity, a playful acceptance of the unknown, becomes an eye for learning, and it might also be why poems grow and die like Zukofsky’s “nothing / Which is a forever,” why Rae makes herself “the butt of a cosmic joke, if that’s how it’s got to be,” because by surrendering to “nothing,” which is a “forever,” to the space (“nothing”) time (“forever”) of physical reality — to the spacetime of physics — we can be time machines, we can turn the “pages back.” If we are lucky, if we are like Zukofsky in his poem, we don’t have to turn to the “last” page as if it were a precipice. The absurdity of the book keeps us gathering somewhere/nowhere in the middle (defined broadly as between the first and last page) until we see that the book is more like a “sea” than a perfect-bound (or saddle-stitched or duct-taped or hand-sewn or digitally-mastered) “speck.” This might make us simultaneously shipwrecked (via Oppen) while sailing to the dangerous ocean’s “edge” (via “Columbus”) until we get there, of course, because we are poets. The horizon keeps on bending. If we are more than lucky, if we are “… like another, and another, who has finished learning / and just begun to learn,” we feel the strength of the salt air …

I struggle with how to “teach” this to my students. The writing exercises, the readings, the thought experiments, the programs, the politics: how do they account for Zukofsky’s nothingforever?

My question about teaching relates to my discovery of the tesseract as a cipher for one of the writers in my borealis. Gilbert asked me to write to our group about my tesseract, but it’s personal, so I must cipher my comments about the cipher. You know.

A tesseract is a 4-D analogue of a cube. Think Salvador Dali’s hybercube christ or Doctor Who’s police box, which is bigger on the inside than the outside. The idea of a tesseract has always been important to me, because poems can be bigger on the inside than the outside. They can alter what I call the “spacetime of the page” in ways that subvert the page as a 2-D context by becoming hyperdimensional. I suspect poems can also affect spacetime, not just the spacetime of the page. This might account for my recent interest in experimenting outside of the page. Which is to say I think poems affect physical reality, hence my interest in physics. So, for me, the tesseract is a metaphor for the poem on one scale, and it’s also a simile, which can approximate physical reality but cannot fully describe it. As such, the tesseract operates at the parameters of perception. The writer I selected to be represented by the tesseract in my borealis also performs his poetry like a line of demarcation. I have a poem titled, “Borealis: Working Notes,” which describes my relationship to the tesseract more than these notes can attempt. Maybe I’ll post it [see the “Poetry Supplement” for the poem].

Retallack: I’ve enjoyed and benefited from reading the five responses to Anew 12. (Are there others? I’ve had difficulties — not only temporal — getting around this website and feel sure there’s much I’ve missed.) A reply to Amy’s pedagogical question — I think a good way to start with this poem in a class — after reading it many times over and discussing and writing “first thoughts” and a “need to know” list — would be to direct students to these responses.

I hereby throw a speculative response into the cauldron.

Puzzling over 12 in conjunction with these readings reminds me how much the work of productive attention — interpretive/associative/researched — requires trust in the author. If one considers 12 an investigative or exploratory poem and, so to speak, takes the poet at his word — then one notices a poet who is wondering in a state of partial knowledge about quantum mechanics as though in a constrained thought experiment, locked in a room without access to books or a friendly physicist eager to explain.

One way to construe this is that the poet is conducting an experimental wager: I will try to understand as much as I can about quantum physics by way of my present fund of poetic knowledge and poetic praxis, nothing more or less. Could this be an enactment of the radical question whether one can come to know certain things by means of poetry alone? Where poetic language is believed to be so funded with intuition, so coherent with the collective consciousness of the times, so intimate with the harmonics of nature, that the following, akin to a Pythagorean system of progressive relations among numbers, can occur: The lettristic first line where “see” and “sea” are permutative variations analogous to the visual presence of “sea” being physiologically dependent on “see” situates the mind itself as a kind of condenser, with its reception and selection processes of all (sound and light waves) the air brings its way. From this position of the mind’s acute receptivity — e.g., to the flowers further along — any instance (mote) radiates limitless possibily.

Specks and motes, of course are metaphors in this context, they don’t behave like particles in complementarity with quantum mechanical waves which are particles just as particles are waves. I’ve come to feel that Zukofsky is not really seeking after the technical terms or the technical knowledge they point to in descriptions of how quantum mechanics works. It seems, if this is a thought experiment of the sort I’ve suggested (and it may not be), Zukofsky doesn’t care if it fails. Or perhaps wants it to fail. He seems to exit the pressures of theoretical physics with a kind of poetic abandon, even a touch of the romantic, bypassing (lower limit?) science for (upper limit?) poetry. He knows his experimental (applied) physics — that of condensers. He knows that frequencies (radio waves) become sound that’s more pleasing with the assistance of condensers. It’s the music he cares about; quantum mechanics may explain something about the action of “phonons,” and “photons” but it doesn’t explain the beauty of the sound, nor does it help with the experience of the “sea” that “see” can become in the transit of light to the retina; nor the experience of the delicious splitting of the homophones see/sea which implies the separation of the presence that is seen from the presence that is heard. We know from physicists that one sees the sea before one hears it. The explanation for that scientific fact doesn’t seem to interest LZ. It’s a speed differential that one can’t register on an experiential level as one can register one’s (and one’s loved one’s) response to a field of flowers. The science in that, as presented in 12, is entirely metaphorical.

More Qs: What is Zukofsky’s (or his persona’s) position with respect to the state of his knowledge as temporally bracketed in this poem? The things he suggests he does and doesn’t know don’t necessarily point to the facts of physics — applied or classical or quantum. On the evidence of Anew 12, I somehow don’t really think Zukofsky wants to learn quantum physics. “Waves of a speck of sea” isn’t quantum physics. Everything about that line, including “or what,” strikes me as humor. What meaning does the poet wish to turn to? It seems he has turned to an observable aesthetics, away from theory by the end of the poem. Though there is that final “Perhaps.” The puzzle doesn’t end, perhaps the thought experiment goes on and it is called poetry of a certain kind, whose relation to science is in question.

Note: before writing this, I went to Mark Scroggins’s Louis Zukofsky and the Poetry of Knowledge. Could find nothing about Anew 12, condensers, quantum physics, science … Next went to a clunky book I’ve had for almost forty years — The Way Things Work: An Illustrated Encyclopedia of Technology — to review the many kinds of condensers and their pretty diagrams. Next I went to an article on the web on condensers in radio transmission and, after a bit more muddling about, to the excerpt I’ve pasted below. All the while more and more aware of the fact that LZ (or his persona) could have done the equivalent of this kind of search, but clearly chose not to.

Electromagnetic waves and sound waves have an obvious resemblance, and the concepts and techniques used in optics are often brought into the acoustic domain and vice versa. One can immediately think of the obvious correspondences between acoustic and optical microscopes, between radar and sonar, and such concepts as electrical and acoustic impedances, all of which highlight this “son et lumière” similarity. Using the language of classical physics, this similarity is a consequence of the fact that the same wave equation governs oscillations of atoms, ions, and molecules in a sound wave and the oscillation of electrical and magnetic fields in an optical wave. And in the language of modern quantum physics the basic quanta of light (photons) and sound (phonons) obey the same rules describing all bosons — particles with integer spin. The most striking consequence of the quantum nature of light is the ability of matter to emit coherent photons of identical frequencies and phases, a process predicted in 1917 by Albert Einstein, who called it “stimulated emission.” (Jacob B. Khurgin, “Phonon Lasers Gain a Sound Foundation,” American Physical Society, February 22, 2010)

Ongoing relations between 'poetry' and 'science'

Edited by Gilbert Adair