Strange homesicknesses: Audrey Hall translates Sara Gallardo

A friend who knows about these things once told me about the existence of a German word, Fernweh, which she translates to mean: feeling homesick for places you've never been. Reverso renders it as wanderlust, but my friend explains the word conveys not so much a lustful craving for travel as a sense of sadness and loss in staying put. A closer approximation might be distance-sickness, filled with all the ache, yearning, and nostalgia that homesickness might evoke, only for far-off places rather than the familiar.

What if someone longed, not for distant lands, but for unknown languages? What would the word be then?

Human language acquisition is thought to begin in utero, and yet an infant's first babbles arrive magical as incantation. What surprise, the non-stop string of words vibrating from a preschool sandbox — about cars, butterflies, dinosaurs — how much a three-year-old has to say!! And how mysterious, the universal occurrence where humans help fluency along with adjustments in cadence, gesture, expression, the gentle correction of cat for dog. Such is the wondrous code of language, utterance as collaborative treasure, waiting only to be uncovered, nudged into waves of sound.

To gain fluency as an adult is a trickier prospect. Particularly after a certain age, learning a new language requires a certain intensity of desire, not wanderlust exactly, but A lustful thread, breath that heats the passing of syllables.

Within the passages of geography, a strait is a narrow natural channel through which a ship might sail from one body of water to another. The term might also be used to convey a challenging situation, as in a tight spot, a crisis or predicament, the skillful navigation of which the entire outcome depends.

The Straits of Magellan — famous for unpredictable winds, treacherous currents, and maze-like paths — is labeled the Dragon's Tail on old sea charts. Commanding a reduced fleet of three vessels, Magellan entered the arduous passage on All Saints' Day, 1520, rechristening it Estrecho de Todos los Santos, or the Channel of All Saints. Nearly 600 kilometers and thirty-eight days later, Magellan and a crew of some-270 sailors emerged to favorable winds skimming the Earth's largest ocean. Magellan is said to have named it Mar Pacifico, peaceful sea. He is said to have wept upon seeing its gentle waves, far-off expanse transformed to the shimmering near.

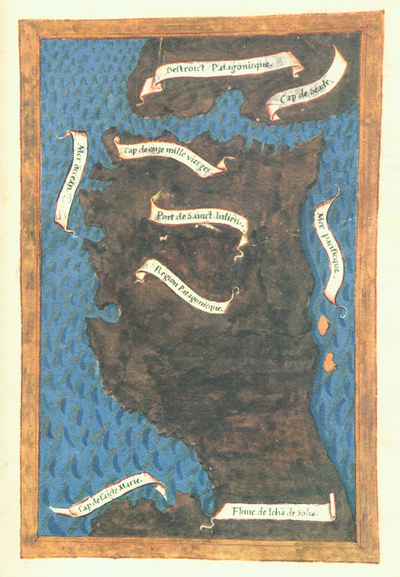

1520: Antonio Pigafetta, "Figure of the Pathagonian Strait."

Leaving my Pacific Coast home one summer to enter the strait of a new language, it was as if I lost access to all prior passages of voice. With my feet in another country, I stumbled constantly over unfamiliar words, but my tongue couldn't articulate familiar ones, either. When kindly shopkeepers offered help in tentative English, all that issued from my own mouth was silence. After several weeks, my facility in the new language grew, but reading in my native one became nearly impossible, a kind of selective aphasia induced by the intensity of want for a different conveyance of meaning.

Limited baggage had allowed few books in any case, but one slender volume pulsed with keen legibility in my oddly illiterate state: Clarice Lispector's Água Viva, newly translated into English by Stefan Tobler for New Directions. Remarking on Lispector's "weird word choices, strange syntax, and lack of interest in conventional grammar," Benjamin Moser observes that her intention "mystical as well as artistic, was to rearrange conventional language to find meaning."

That summer, adrift in the linguistic strait between familiar and strange, Lispector's singular rearrangements of language became the sextant by which I might navigate safe passage to new waters. The first paragraph of Água Viva sent a flare: I am a little scared: scared of surrendering completely because the next instant is the unknown. The next instant, do I make it? or does it make itself? We make it together with our breath.

Until the Panama Canal opened in 1914, the Strait of Magellan served as the main route for steamships traveling from the Atlantic to the Pacific. Geographically, it remains a significant natural waterway connecting the two oceans, but unlike the Drake Passage, it also divides lands — continental South America from the archipelago of Tierra del Fuego, the eastern part of which today belongs to Argentina.

What to call homesickness not for a place, nor a language, but for lands divided without passage?

Along the California-Baja border, there exists an emergency door that swings open once a year. This spring, five families were permitted to gather under the lintel with loved ones who must otherwise live opposite sides of a barrier wall. Parents embrace children. Sisters weep on each other's shoulders. Grandparents whisper in toddlers' ears. Twenty precious minutes before the door is locked again.

What would be the word for this kind of longing, the inconsolable homesickness for one another?

What syllables, whose breath would speak them? And where, and when?

In his late-20th-century lecture, "The Paradigm of Translation," Paul Ricoeur suggests such a language might be brought into being by passage through the door of the unfamiliar: "There is something foreign in every other. It is as several people that we define, that we reformulate, that we explain, that we try to say the same thing in another way."

To speak is to expel breath through the vocal cords to produce a particular pattern of sounds. Through the strait of the larynx, brain connects with lung, exhalation of syllables into air.

Some say the right words arrive when we are ready. Maybe passed through breath or babblings. Maybe we want, urgently, "to say the same thing in another way," and in that ardent wanting, the words gain passage through the strait of translation.

The first time I heard the words of Argentine author Sara Gallardo, I heard them spoken aloud by a young woman raised in a home of many languages. Audrey Hall read her translation from Spanish to English to a ballroom filled with open ears, syllables of astounding beauty conveyed in the wake of yearning.

Translation compelled by longing.

Could it be that what I am writing you is beyond thought? Reason is what it isn't. Whoever can stop reasoning — which is terribly difficult — let them come along with me.

That summer, in the strait between languages, it wasn't home I longed for, but a country just beyond thought. The cold of snowflakes, the taste of tall grasses through wind.

•

From the novel January by Sara Gallardo

With translation from the Spanish & original commentary by Audrey Hall

She kicks her horse into a gallop, keeping to the tall grasses where the hoofbeats are muffled. She’d rather not think about the end of her journey, about that old woman whom she’s never seen but in whom she has placed all her hopes. Everyday things take on undue significance as her eyes consider them, one by one. Thistle, she says to herself, thistle, quail, dung, anthill, heat, and then she listens to the one, two three, four, one, two, three, four of the horse’s hooves beating the ground. Slowly, sweat appears behind the horse’s ears and runs in cloudy threads down his neck, where the chafing of the reins churns up dirty foam. Little voices, little voices speak to Nefer, but she ignores them. Cow, she thinks. Spotted cow, another and another. That one looks sunburnt. Lapwings. Two lapwings and a fat pigeon. Screaming so loud!

The path is an immense, empty tongue. Nefer watches her shadow gallop across the ground; she shifts her position, adjusts the angle of her arm, and twists her head around to see what changes she can make to it. Sweat streaks the horse’s haunches and starts dripping down his legs; Nefer looks down at the palm of her hand, where dirt shades in every crease.

“Hey there, Dapple,” she murmurs, “You’ll have the day off tomorrow, eh? I’ll slip you some corn when no one’s looking. You like that? Tomorrow you’ll rest … Tomorrow when the mission starts and …” A sudden bump in the road throws her thoughts off course, but a bitter taste lingers in her chest.

After walking through pastures and crossing the railroad tracks, after not seeing anyone for over an hour, when the tall grasses grow sparse over the ashy ground and the horse’s sweat has turned bluish, Nefer comes across a farmhouse in the translucent oven of the afternoon. As it comes into view, her heart shrinks.

Far away, where the tala trees form a dark eyebrow, Don Pedro’s sister lives with her family. But she isn’t worrying about them right now, she’s not worrying about anything but this flattened little farmhouse next to the huge, dry eucalyptus where nothing moves.

Why did I come?

A powerful homesickness fills her suddenly. She is surprised by how many ideas her memory holds about the people she has come to see, that family whose last names mysteriously interweave, with an uncle who used to practice black magic and a grandmother who is a witch doctor.

Nefer closes her hand over the damp reins and runs her tongue over her lips. Then her soul goes dark again and the road continues on, curving around towards the house.

* * *

A crumpled figure draped in thick, silent summer heat: a woman on horseback, embarking on a journey towards something familiar-grown-strange, the stuff of local gossip and late-night childhood ghost stories. Everywhere she looks, she sees filth: the horse’s sweat-slicked coat; the mounds of shit in the road; dirt etched into her palm; the very earth beneath her turned to ashes. This bright, wide-open day feels to her like a dark oven, a cloying heat that strangles, just as she longs to strangle the little voice whining inside the dark oven of her womb, a life born of hurt and humiliation and confusion, of roaring pain and jagged, wine-soaked breath. An invisible, insatiable parasite that devours her future, her parents’ trust, her unrequited dreams of love, that merest glimpse of a life fully lived. She bursts out of her skin to think of it, twists herself into every possible contortion, gallops brutally hard with her heart in her throat and the lapwings screaming, wheeling, eternal, overhead.

•

Audrey Hall has translated a range of short and long stories, children’s books, scholarly essays, and historical texts from Spanish into English. A 2015 ALTA Travel Fellow, she holds a BA in Comparative Literature from Princeton University and received a Fulbright Study/Research Grant for literary translation in 2014.

Sara Gallardo (1931-1988) was the brilliant yet understated author of five full-length novels, several children's books, and a book of short fantastical stories, which she called "The Land of Smoke" in reference to her native Argentina. The excerpt translated here is taken from her first novel, January, published in 1958.

•

Notes:

Clarice Lispector, Água Viva, trans. Stefan Tobler; intro. & ed. Benjamin Moser (New York: New Directions, 2012), 20, xii, 3, xiii.

Paul Ricoeur, "The Paradigm of Translation," On Translation, trans. Eileen Brennan, intro. Richard Kearney (London: Routledge, 2006), 25.

Peter Rowe, "Where a wall already divides," Los Angeles Times, May 2, 2016.

Map image: Antonio Pigafetta, “Figure of the Pathagonian Strait. Of the region of Pathagonia. Ocean Sea. Of the Pacific Sea. And Other Capes.” The Strait of Magellen: 250 Years of Maps (1520-1787), online exhibition curated by John Delaney, Princeton University Library, 2010 with permsission of the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

A poetics of the étrangère