Strange wanderings: Claire Eder translates Christian Prigent

Apples fall from tree branches, and vibrations of colliding stars pass through light years. Such do gravitational forces magnify quotidian wonders. How best for earth-bound travelers to cross curvatures of time and space? Poet Claire Eder ventures into an ancient city of the dead to translate another poet's voyage and happens upon inexplicable strangeness from atop a library perch.

"Not everyone is given access to this other world where the dead and the dying live," Hélène Cixous reminds us, mortal humans, in "The School of Dreams." But if we cannot reasonably be guests of the dead while we are still living, we might still, Cixous suggests, "go there by dreaming."

Dreamer as traveler, a notion transported inside language, rêve—French word for dream—wandering easily into river, carrying passengers across to unknown countries, no ticket for the ferryman.

Another way to dream in French is songer: to think about, to envisage, to muse, contemplate, wonder. Drifting between two shores of dream language, songer conveys more lyrical freight, a verb linked to a possible future, not to sleep—though rêver might also stray into vision, daydream, imagined desire. As a noun, un rêve can also verge into nightmare, where un songe never does.

In mid-twentieth century Paris, a collective of artists, writers, and visionary imaginers set out on foot to remap individual experience of urban landscape through unplanned encounters. As defined by Situational theorist Guy Debord, the dérive—French for drift—is a practice in which "one or more persons during a certain period drop their relations, their work and leisure activities, and all their other usual motives for movement and action, and let themselves be drawn by the attractions of the terrain and the encounters they find there."

Drifting as a means of upending habit, of bypassing usual routes in resistance to becoming a tourist in the existing cartography. The dreamer resists sleepwalking, the kind of somnolence that falls into death.

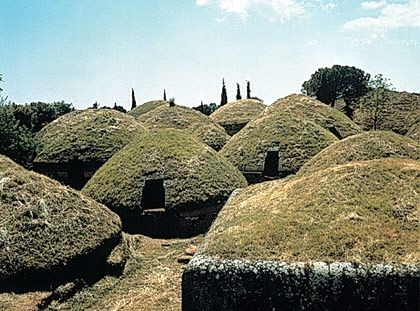

As inscribed in its name, a necropolis is not merely a burial site, but a city of the dead, and the necropolis at Cerveteri was organized as an urban plan, complete with streets, squares and neighborhoods. Even its above-ground tombs were constructed like houses, "providing archaeologists with the best and only evidence of Etruscan residential architecture, as such structures have not survived in the archaeological record." Located within an hour's drive from Rome and dedicated in 2004 as a UNESCO World Heritage site, Cerveteri is visited by thousands of tourists every year.

How to cross the curvature between the known and the strange? How not to topple into the gap between tourism and waking dream?

For a brief time, I lived in the small French city of Tours, and—bewildered by unfamiliar streets—left all my crossings to the chance of signals. If one light flashed green before another, that's the course I took. The strategy wasn't compelled by rebellion so much as blind trust, but it did allow a particular orientation over a long-standing, ever-evolving map. One friend there resided in an apartment building dating from the Middle Ages. It stands a few blocks west of a university built in 1970. The city itself is located between two rivers, the Loire and the Cher. One morning along the south bank of the Loire, I saw a man walking a goat on a leash. The goat wore a hat, as if to disguise its small horns. We all three of us meandered along.

My friend who lived in the medieval construction spoke little English, and I, little French. Still, we managed a conveyance of understanding, lifting each other into new words, enunciations, and nuances. Songe is one form of dreaming, and in English une songerie translates to reverie: a waking dream, a delirium, a losing into thought.

Maybe closer to rêve, reverie tumbles into river, coursing us to a long-departed world known only by the remnants of a city plan. Such sites might still be visited via aircraft. Or a dreamer might wander the heights of a library staircase to gaze into another time and place from the window seat of a book. One, titled The Poetics of Reverie, confirms the mode of transport: "Yes, words really do dream."

•

Etruscan Dream: Translating Christian Prigent

by Claire Eder

I went underground, into the homes of the dead, and then I came back up. How did I enter the homes of the dead? I received an invitation.

Okay, I didn’t really go underground. But I went to the library. I was working with the poems of contemporary French poet Christian Prigent, specifically his series “Le Voyage d’Italie” / “Travels in Italy.” This series explores the overlapping layers of Italian civilization and art, from the urban landscape of contemporary Rome to the Renaissance frescos of Luca Signorelli to the Etruscans, an ancient civilization that flourished in Italy from the 8th century BC until it was conquered by the Romans in the 3rd century BC. It was the Etruscans who sent me to the library.

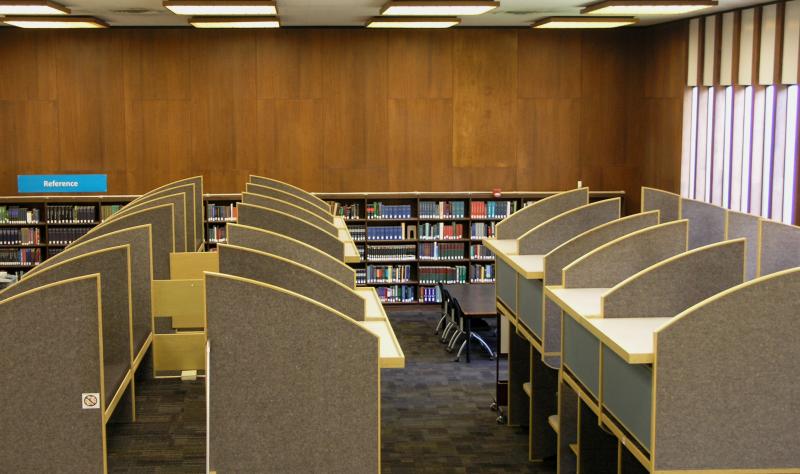

I found the book I needed and I took it to the top of an intriguing structure: a double-decker study carol, one of many little towers in the middle of the high-ceilinged library. You climb the stairs and sit on a platform above other readers (cave-dwellers), in this sort of crow’s nest of six or so desks. (You see how I automatically chose the height, not the underneath place.) Thus strangely ensconced, I found the images.

An Etruscan necropolis like the one at Cerveteri consists of closely spaced structures that look like circular huts, with domed roofs, everything totally covered in grass. Each has a door, a rectangle of shadow interrupting the grown-over blocks of tufa stone. I entered. In the damp of the stone chambers, paint flakes away, but the colors are still bright. I was in search of a character called Phersu, the main subject of one of Prigent’s poems. “Un matin / après le tintouin / Phersu / et le marteau” (“One morning / after the brouhaha : / Phersu / and the hammer” [“rêve étrusque” / “Etruscan Dream,” my translation]). When I found him, he was holding a rope attached to a dog. The dog is attacking a bleeding figure, perhaps a prisoner, with a hood over his head and a club in his hand. Was this club the “hammer” Prigent mentions? Phersu’s face is hidden behind a smiling mask with a long, pointed black beard, and he wears a short tunic and a cap with a peak. Amalia Avramidou claims that the name Phersu is likely related to the Latin word “persona,” which explains the mask and the aspect of performance he embodies as he conducts such rituals as the one depicted in this fresco, thought to be a sort of funerary game.

The scene frightened me, intrigued me, left me with nothing solid to hold on to. This was what I needed. I was turning into Phersu, putting on my mask of language and performing, as Prigent demanded, a dance for death.

The Etruscan language remains a mystery to scholars, largely impossible to translate. The most substantial text was discovered written on the grave wrappings of a mummified Egyptian woman: a linen book dating to the 3rd century BC that had been cut into strips for this use. Upon examining this “Book of the Mummy” after its discovery in 1892, scholars could identify enough words to postulate that it was a religious text, probably a calendar prescribing sacrifices for certain ritual occasions. Agnes Carr Vaughan writes, “The problem presented by the Book of the Mummy teases the imagination. One wonders who the woman was. That she was young has been determined, but not why a cloth book was torn into strips to provide wrappings for her mummy, nor how an Etruscan religious text got into Egypt.”

Prigent’s poems stripped away layer after layer of history, and underneath was a body. The poems return relentlessly to the dead; to the casket, sarcophagus, tomb, or pyre; to the sheer masses of the dead; to the end of a civilization. He invited my imagination to confront its fear and to enter the burial mound. And then he left me with a pile of wrappings: translation’s glorious and unsolvable mystery.

•

Claire Eder’s poems and translations are forthcoming or have appeared in the Cincinnati Review, Subtropics, the Florida Review, [PANK], Midwestern Gothic, The Common, and Guernica, among other publications. In 2015, she was selected to receive an American Literary Translators Association (ALTA) Travel Fellowship. She graduated from the University of Florida’s MFA program and is currently pursuing a PhD in poetry at Ohio University.

Christian Prigent was born in Saint-Brieuc in 1945. He has lived in Rome and Berlin and currently resides in Brittany. He earned a doctorate, writing a dissertation on the poetry of Francis Ponge, and from 1967 to 2005 taught French language and literature at the high school level. In 1969 he founded the avant-garde journal TXT and the TXT book series, which he directed until 1993. He is the author of some forty books of poetry, fiction, non-fiction, interviews, and essays on literature and painting. He regularly gives public readings of his work throughout the world. His most recent publications include Les Enfances Chino [Chino’s Childhoods] (2013, fiction), La Vie moderne [Modern Life] (2012, poetry), and La Langue et ses monstres [Language and Its Monsters] (2014, essays).

•

Notes:

Amalia Avramidou, “The Phersu Game Revisited,” Etruscan Studies 12 (2009): 73-87.

Agnes Carr Vaughan, Those Mysterious Etruscans (New York: Doubleday, 1964).

Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Reverie, trans. Daniel Russell (Boston: Beacon Press, 1969), 18.

Hélène Cixous, "The School of Dreams," Three Steps on the Ladder of Writing, trans. Sarah Cornell and Susan Sellers (New York: Columbia University Press), 59.

Guy Debord, "Theory of the Dérive," trans. Ken Knabb, Les Lèvres Nues #9 (November, 1956), reprinted in Internationale Situationniste #2 (December, 1958). Accessed at Situationist International Online, March 2, 2016.

A poetics of the étrangère