Translated presence: Genevieve Kaplan & technologies of bookmaking

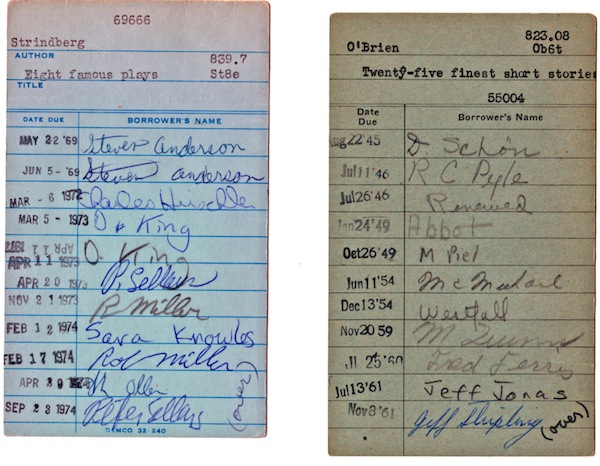

Some books come to us by way of friends, some by strangers, tucked into an anonymous mailer by someone we will never meet. Not so very long ago (and maybe in some places still), you might have opened a book on a library desk and seen, listed inside the back cover, the signatures of all those who opened it before.

school library circulation cards, mid-twentieth century. Photo, Paul Lukas.

school library circulation cards, mid-twentieth century. Photo, Paul Lukas.

Not so very long before that (and in some places still), to open a book under any circumstances signified a remarkable convergence of birth, opportunity, and chance. In some cases, it meant you were a king. In others, it meant being on very good terms with one.

In the early years of the fifteenth century, an Italian-born poet named Christine de Pizan not only opened a king's books, she made them. While the exact details remain a source of study, it's certain Christine conceived the ideas, scribed many of the letters, and engaged a brilliant illuminator named Anastasie to produce elegant manuscripts for the French royal family. When luck was with her, the wealthy nobles rewarded Christine with handsome sums, which the young widow used to feed, clothe, and house herself, along with her three children, adopted niece, and widowed mother.

As daughter of a court physician and astrologer, Christine had rare access to the library of Charles V, a vast store of some 1,200 volumes, the basis of today's Bibliothèque nationale. Charles, known as the Wise King, commissioned numerous translations to reflect his prestige and power, and this is likely how Christine came to read such books as Aristotle's Ethics and St. Augustine's City of God, both of which figure in her own creations. Dante's Commedia is another presence, keenly felt. As it happens, Christine was the first author in France to make use of the Inferno as a model for her own work.

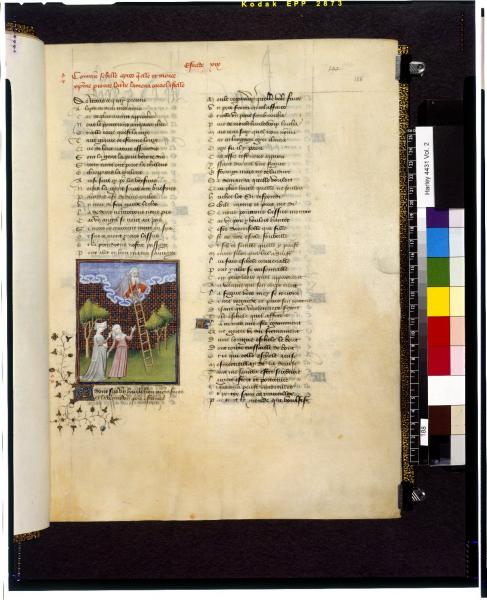

As Dante was guided by Virgil, Christine is guided to new realms by the Cumaean Sybil. Harley MS 4431, f 118r

Lines from Dante appear in Christine's Book of the Path of Long Study as if transported directly from the startling vernacular of the First Canto, and I imagine Christine coming upon the exiled poet's bello stilo for the first time, alone in the king's library, dumbstruck with excitement to see the language of her birth scribed in a book. Maybe she read a bit each night the storied venture through a strange and terrifying landscape. Maybe she read aloud to her aging mother, her voice sounding cherished syllables of a country neither would ever see again.

Maybe her children joined in the listening.

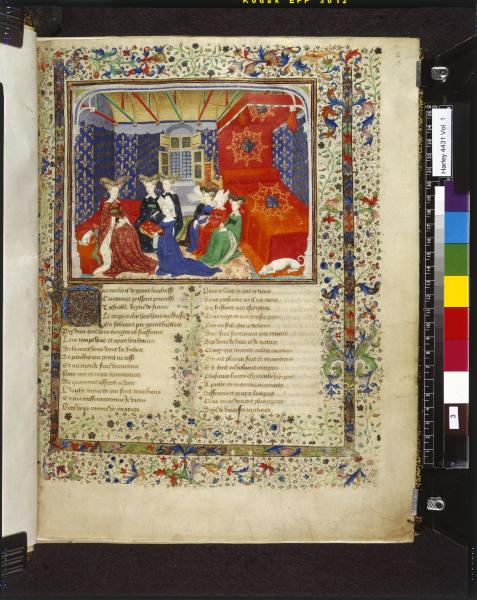

This imagining is one of my own making, but it's certain what happened to the book containing some of the first translated words of Dante's Italian into French. We have pictures, gilded. Here's one that shows Christine presenting the finely produced manuscript now known as Harley 4431 to Isabeau of Bavaria, queen consort of Charles VI.

British Library Harley MS 4431, f 003r

How The Book of the Queen came to be in the holdings of the British Library is another story of venturing, but you can open the whole of it here, with a click of your hand.

Such a book is known as a presentation copy, and Christine is believed to have presented this one as a New Year's gift in January, 1414. Depicted in the offering is a communal gathering, for to present a thing is also to invoke the presence of others as recipients, present shifting from verb to noun to adjective. To be present is to exist at a particular place and time, but more than that, it is to exist in the presence of someone else. Such presence might be embodied physically. It might occur in reverie. It might arrive — as it does in Christine's vividly colored miniature — in the form of a book.

And so to make a book, to present it to others — to make of it a presence in the world — is to make a kind of gift, not simply of vellum and ink, but of existence.

It is also to make a wager, as any bookmaker will tell you. Of course, the word bookmaking might be taken to mean exactly as it appears: the undertaking of designing, printing, and binding a physical object that we might then open to find even more words — with any luck, the right ones in the right order. In another context, the term might also wear a poker face, one equated with the practice of laying bets on the various outcomes of a single event.

As a made thing, a book stands as one of countless possible outcomes that might be constructed of language. It exists as a material presence, but maybe its truest gift is a bet on the future, staking the language of the already written for the language to come. So did Dante make his way to a widowed mother such that she might imagine her own path to heaven. So might a reader today (with opportunity and luck) gain instant access to a queen's book — knowledge that might animate new presences of language.

A bookie might be the only bookmaker said to invite bets, but every invitation holds a gamble inside: What are the odds the guests will arrive? For some, it's a calculated procedure; for others, an extra plate is set out as a matter of course. In the company of presents and bookmakers, Paul Ricoeur reminds us of the risk: Each of our words has more than one meaning.

And of the assurance: Even in the absence of bets, throughout the world sentences flutter between [humans] like elusive butterflies. Despite all improbability, even the untranslatable finds passage, a maker to bring new sentences to shore: We have always translated: there always were the merchants, the travellers, the ambassadors, the spies to satisfy the need to extend human exchanges.

To this list of linguistic traders might be added the chapman, those roguish peddlers who journeyed throughout this same world in other times, carrying with them sentences that others might wish to hold. These sentences were printed on single sheets of paper, folded into small gatherings until slit open by someone with enough opportunity and luck to trade them for a penny. Such did a reader become part of a book's making, transforming presence into pages, translating long shot into reality.

What new realities might have taken root as a result of these exchanges is anyone's guess, but form is one way idea flowers into fruit, and Noah Eli Gordon likens the chapman to a kind of Johnny Appleseed of early literary education, whose wares brought literature and news of the day into the presence of even the most distantly located readers.

In her exploration of more recent technologies of transformation, Mathelinda Nabugodi speaks to literary production as it intersects both with means of access and the task of the translator: Technological innovation does not simply improve on existing art forms, but is capable of generating new art forms by offering new media for artistic creation. Such might the presence of new technologies seed new possibilities for language.

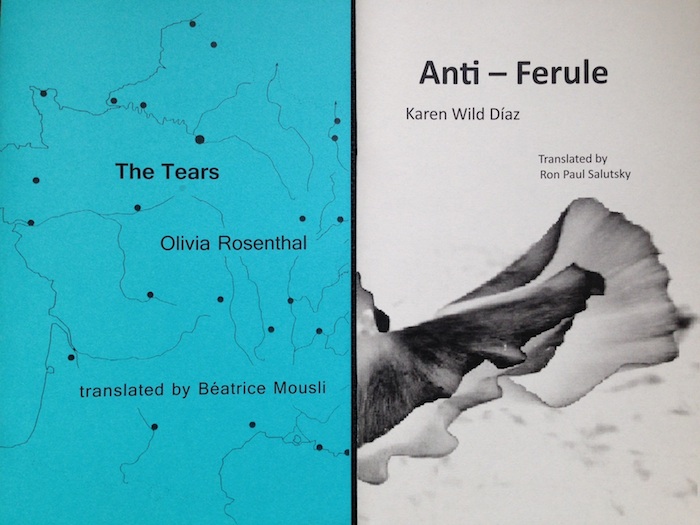

Not so very long ago a thick envelope passed through the mail slot of the front door. Chado barked with enthusiasm, as he always does when the post appears. Inscribed on the outer wrapping: my name, the address of my house. Inside: two slender books of translation, thoughtfully-made, an exquisite simplicity.

selections from the Toad Press International Chapbook Series

As it chance would have it, the books arrived on my birthday, and I knew exactly whose hands had done the making, whose hands had placed the gifts inside the package.

What presence might grow from the seeds pressed inside the covers, only fortune can tell.

in the face of danger, my legs stretch

i grow tall, towering

there high above, silence

—Victoria Estol

•

Publisher's Note: An Invitation

by Genevieve Kaplan

We receive many amazing and publishable submissions during our annual open reading periods, and in a more ideal world, I’d like to publish most of them — maybe 12 chapbooks a year with one book appearing each month. I could think of them seasonally: which collection is February, which feels like September? And which September, in what language? A wreath, a calendar of possibilities.

But there’s always the disconnect between what is possible in the mind and what is possible in the world. As a publisher, the problem for me is in deciding. And being luckily, happily, faced with such rich material, I wonder: how best to present it to the world?

So I’m always thinking not just of the poem(s) or the language or the translation, but also of the book. I work with the constraint of traditional chapbook size and format: standard paper, folded in half and stapled to become a 5½ x 8½” booklet — I want to make sure I consider not only what the form allows (or doesn’t), but also of the reader’s potential experience with the book. The chapbook is a snapshot, I think. It can be experienced quickly, it should offer enough to satisfy, it should be complete. It should also potentially leave readers wanting more. How will [title] read as a product or project, how can I best help readers to experience it?

In our forthcoming title mainland, Danish poet Stinne Storm writes:

cuttlebone stranded in the window

pheasant he runs over the roof several times the same place birch

Several times the same place, these striking and inhuman fragments rush over the roof, into the window, and hang in the air, float upon the white space of the page . . . but the function of the chapbook is to bind them together, to hold them in. The folded seam of the book, the piercing staples will ground them.

Other collections already have a relationship with the margins, always accounting for — while straining against — the gutter of the pages. Tiffany Higgins translates Alice Sant’Anna’s poems from the Portuguese, and Tail of the Whale (coming summer 2016) reminds us:

THERE’S SOMETHING THAT REMAINS FIRM (A POST)

and doesn’t move and there’s something that stirs (a tree)

and makes a ruckus and ends up like an octopus with tentacles

trying to grab at clouds, as opposed to the

mountains

Such work comes to us from everywhere and, importantly, takes us everywhere. Paul Cunningham’s soon-to-be-published translations of Swedish writer Sara Tuss Efrik’s project The Night’s Belly is a disturbing adventure, and we are invited to attend:

She follows a decapitated bird. After each footstep a frost settles like a film over nature. On her journey, she finds an abandoned cottage with mullioned windows. The cottage is pungent & puffy.

What is just around the corner? What is just inside the cover? Which page of the journey will you open to?

As the act of translation offers a series of possibilities, so too does distilling that new literature into a material chapbook form. As publishers, let us aim to choose the most exciting, the most effortless-seeming, the most inevitable, the most ordinary, the most wonderful presentations of text. We want you to read it. Let us present something to you.

•

Genevieve Kaplan is the author of In the ice house (Red Hen Press), winner of the A Room of Her Own Foundation's poetry publication prize, and settings for these scenes (Convulsive Editions), a chapbook of continual erasures. She lives and writes in Southern California, where she also coordinates the Kingsley & Kate Tufts Poetry Awards, works as an occasional adjunct professor, and publishes contemporary translations of poetry and prose through the Toad Press International Chapbook Series.

•

Notes:

Karen Wild Díaz, Anti-Ferule, trans. Ron Paul Salutsky, Toad Press, 2015.

Victoria Estol, roly poly / bicho bola, trans. Seth Michelson, Toad Press, 2014.

Noah Eli Gordon, "Considering Chapbooks: A Brief History of the Little Book," Jacket 34 – October 2007.

Mathelinda Nabugodi, "Pure Language 2.0: Walter Benjamin's Theory of Language and Translation Technology," Feedback/Open Humanities Press, May 19, 2014.

Paul Ricoeur, "A 'passage': translating the untranslatable," On Translation, trans. Eileen Brennan, intro. Richard Kearney (London: Routledge, 2006), 31-32.

Olivia Rosenthal, The Tears, trans. Béatrice Mousli, Toad Press, 2015.

Christine de Pizan, The Making of the Queen's Manuscript, collaborative project of Edinburgh University, Project Director, Professor James Laidlaw. Images of Harley MS4431, British Library, Digitised Manuscripts.

Christine de Pizan, The Path of Long Study, trans. by Kevin Brownlee in Selected Writings, ed. Renate Blumenfeld-Kosinski (New York: W.W. Norton, 1997), 59-87. For a complete translation into modern French of Christine's The Path of Long Study, please see Andrea Tarnowski's Le chemin de longue étude (Paris: Lettres Gothiques, 2000). Further information about Christine can be found in Charity Cannon Willard's Christine de Pizan: Her Life and Works (New York: Persea, 1984).

The lines from Dante that Christine translates into her Le Chemin de Longue Étude appear in Inferno, Canto I.83-85: O glory and light of other poets, let the long study and the great love that has made me search thy volume avail me. Kevin Brownlee notes that "the title of Christine's book is thus shown to be derived from Dante's model text."(74.n.2). Additionally, Andrea Tarnowski credits Christine as the "second author in France, after Philippe de Mézières" to speak of Dante, "but she was the first to make use of the Inferno as a model for her own work" (155n.3, my translation).

For translations and new presences compelled by past makings of Christine, please see: «Venditions» and «Moëttes». More about the wagers Christine made as a bookmaker can be found in "Poet for Hire: Christine de Pizan & the Economy of Writing as a Woman." (Drunken Boat.21 & Matter Monthly.14)

A poetics of the étrangère