Curious excavations: María José Giménez on poetry, translation, & other crucial cross-sections

María José Giménez writes of stories contained in histories, of how words fold into other words, of how meaning emerges along the creases. She writes about crossings of language, asks What happens when we engage more closely with other/others' words?, and the question carries me to a history where the words of others required particularly close attention.

In the century before this one, I worked with young children, age six going on seven, just learning how to read and write. Daily, stories arrived on my desk with inverted letters, missing spaces, best guesses. What adventure this emerging language! — inscribed with number 2 pencil on blue-lined newsprint, records of words written for the very first time.

We kept a collection of curiosities on a large table, things passed along or found, not costly but treasured. Keys, crystals, pinecones, rocks. A small brass kaleidoscope, the insides of a rotary phone, a Polaroid camera with no film.

The bookshelf held a discarded encyclopedia set for finding out more about what was on the table because the Internet was still a rarity, and a classroom like that always has a lot of questions.

One day, a student brought a slender box with gold lid. Inside: a perfectly fossilized fish. We took turns with the magnifying glass, every skeletal detail preserved in soft, flat rock.

We turned to the encyclopedia entry for fossil, and I translated the tiny print, how a creature of the ocean becomes encased in earth, how it becomes a record of the past. Still, we wanted more. We wanted everything!

We checked out books from the school library, inspected pictures and diagrams, compiled lists of unknown words: sedimentary, paleontology, compression, erosion.

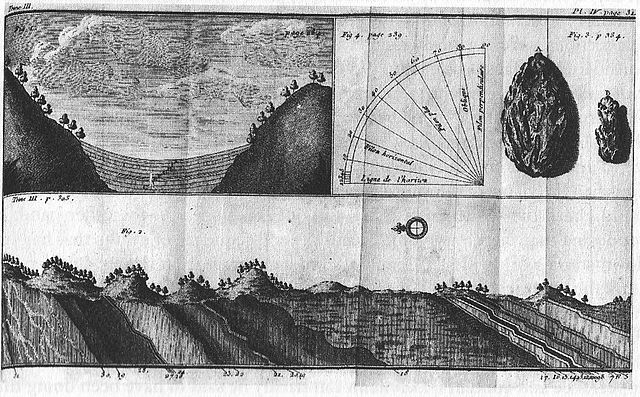

Johann Gottlob, geological cross-section of strata in Thuringia, Germany, 1759.

As it happens, the formation of a fossil requires a rare convergence of events: a plant or an animal must die in the right circumstances, not decompose or be scavenged before getting buried in mud, sand, or soil. Hard bits like bones and shell must remain undisturbed by weather, wildlife, and geological forces. A precise combination of minerals, chemicals, and compression must effect a transformation. These conditions must be met over thousands of years.

Acquiring such a construction is a whole other story.

Once formed, a fossil — along with the rock holding its shape — must remain intact, a trickier prospect than might be evident. Left in nature, both fossil and rock are eventually worn away by the elements; closer to civilization, the threats are endless. The whole delicate arrangement must then be found, extracted, preserved. To have arrived whole — displayed on cotton in a gold-lidded box — was scarcely comprehensible. Maybe our fish fossil had been artificially produced, but that didn't make the whole enterprise any less remarkable, the possibilities of nature any less wondrous, the surrounding vocabulary any less strange.

We set about examining the words, an endeavor with its own curious terms — etymology, easily confused with entomology, evidence of how closely the study of words veers into the study of insects: both invite close attention. And both evoke a certain precision, insects having segmented bodies, and word origins comprising meaning. The dissections of analysis are said to yield truth. But so, too, the compositions of synthesis.

As it happens, sedimentary rock holds layers formed of sand, shells, pebbles. Might the chalk in our hands (yes, chalk!) contain secret fragments? Might they be revealed as we marked lines and drew curves on small, green rectangles?

These are completely viable questions.

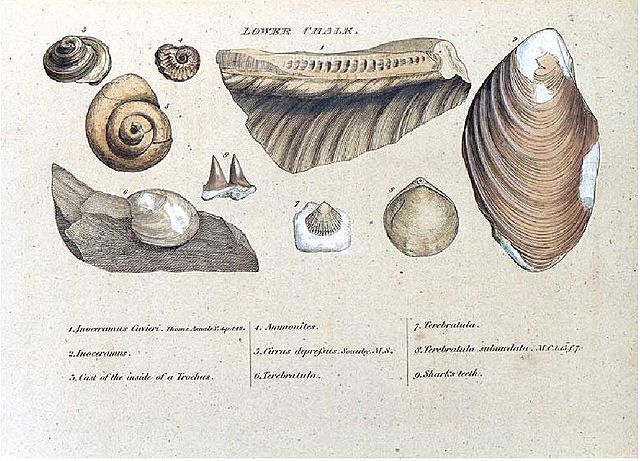

Engraving from William Smith's monograph on identifying strata by fossils, 1815.

In those days, I might go to a party, and upon mentioning that I worked with young children be met with Oh, how adorable! Which is a completely viable response, because with their disproportionately large heads and gap-toothed smiles, humans of six and seven can be unmitigated adorableness. This doesn't make their inquiries any less serious, their endeavors less monumental, their excavations less profound.

You may or may not remember treasures on an early classroom table, hunting a sandbox for fossils, learning how to read and write. Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak proposes language to be one of many elements that allows us to make sense of things, ourselves and suggests translation as the most intimate act of reading. Maybe it is also true that reading — which is to say, learning to read— is the most intimate act of translation.

Akin to translation, acquiring literacy — in one's original language or in another — requires its own settling into attention, a kind of delving into layers, sifting through such oddities as why the same letter causes the face to smile inside one word and not another. Kindness that contains kin, the family likenesses inscribed in our histories.

As it happens, the word paleontology derives from a mélange of three sources: PALEO + ONTO + LOGY, which is to say, language holds its own complex sediments. Upon closer examination:

PALEO: ancient, old; of or belonging to ancient times, esp. the geological or prehistoric past

ONTO: Forming nouns with the sense ‘of or relating to being or existence’

LOGY: names of sciences or departments of study.

Excavating more deeply, PALEO reveals an even older story conveyed in part by an ancient alphabet I am unable to read without translation by the tiny print of the OED:

Etymology: Of multiple origins. Partly a borrowing from Latin. Partly a borrowing from Greek.

Etymons: Latin palaeo-; Greek παλαιο-. < classical Latin and scientific Latin palaeo- and its etymon ancient Greek παλαιο-, combining form (in e.g. παλαιόπλουτος full of ancient wealth, παλαιόϕρων having the wisdom of age; also παλαι- in e.g. παλαιγενής born long ago) of παλαιός old, ancient < πάλαι long ago, of uncertain origin.

Under the magnifying glass, these particular elements crystallize: full of ancient wealth, having the wisdom of age.

The oldest story on record: right there on the table, among the curiosities, in a gold-lidded box brought by a young human just beginning to dig.

•

On Poetry, Translation, & Other Crucial Cross-Sections

by María José Giménez

[1]

A word’s etymology tells a story; a quick look at the evolution of a word reveals strata of human history. Everything we cross paths with — places, people, art, literature, sensory experiences — leaves a mark, changing our accent, the words we use and how we use them. The languages I speak affect how I convey my experience in each of them. One language may require me to merge, and another, to split in two and make a choice. Two examples: The verb “to be” is être in French but ser and estar in Spanish, my first language, in which both “story” and “history” can be translated as historia.

What happens when we engage more closely with other/others’ words? Something lingers. “What remains?” is a recurring question at the intersection of my writing and translation practices. Alejandro Saravia, one of the authors I translate, wrote recently in response to one of my poems:

Un poema que se queda en nosotros es el que nos pide una respuesta: ¿qué hago ahora?

[My translation: A poem that stays/dwells/remains/lingers in us is one that asks for an answer, “What do I do now?”]

Quedar(se) is derived from quietus [still]. Saravia’s comment points directly to what has been the crux interpretum of my creative practice in recent years: The embodied experience, unearthing that which lingers, where movement and stillness meet and reception can become an urge to act. What remains can be explored within the crucial juncture of verbal and nonverbal, inner and outer, of what’s familiar and what’s other.

[2]

My writing and translation practices exist separately but don’t always respect each other’s boundaries. They are intertwined, like the languages I speak. Engaging with the written word (reading, writing, or translating) feeds my creative process in a direct way, sometimes blurring the line between mine and other. It often entails a proprioceptive experience that commands my attention and a subsequent action. For example, a word or image may stir an urge to doodle, move, delve into its etymology, or write a poem or letter to a character in the story. Something drives me to act, the way a beat may compel me to dance, or hearing someone read a poem stills my entire body into listening. Sometimes I take the process further using the experience as a prompt for freewriting (writing without lifting my pen for a certain amount of time no matter what comes out). This has been my writing practice for over 15 years, via Natalie Goldberg and, more recently, Jena Schwartz. It provides a space of constrained freedom, a meditation cushion of sorts that offers the safety of having nowhere to go.

A writer is not so much someone who has something to say as he is someone who has found a process that will bring about new things he would not have thought of if he had not started to say them.

—William Stafford

[3]

Writing/translating a poem can be a gentle, tender act, like holding a wounded bird, knowing all I can do is let go, hope it will fly, not die, and trust that all will be well either way. Other times, it feels almost violent, guided by instinct, like hunting and field dressing a deer and biting into the still-beating liver:

I look for a long time at the body of a poem

until I lose sight of what is not the body

and feel, bursting loose between my teeth,

a thin cord of blood

in my gums

From “Primera lição”/“First Lesson” by Ana Cristina César

Trans. Michelle Gil-Montero

A spectrum lies between the two extremes, the connective tissue being my practice of engaging with the liminal by exploring a place between or beyond — a sea of proto-etymons.

Digging beneath the outer shell of a word or poem (mine or one I’m translating) unveils its edges, textures, sounds, essence. There is free, instinctual movement not unlike wandering through a city I know and love, such as Montreal (a threshold city, an island in a river, never still, always translating itself), or moving in a familiar space in complete darkness. I know where to slow down and move with care. Even when I can’t see exactly where I am, I know I can find my way.

[4]

ETYMON

are we not vessels, hollow buoyant holds

spines masts rising from pelvis, sacra keels

do bones not flow with urgent spring sap

arteries with vital fluvial spirits

are nerves not a seamless

hyphal web, mycelium dancing

skin woven, muscles sinewed

with leaf veins, tree roots

the heart the inmost molten core

beating tremors, cracking crusts

until we decay to dust

spinal cord pithed by Death

to still that restless sense

the truest beast inside us

•

María José Giménez is a Venezuelan-Canadian poet and translator. Her publications include original and translated poetry, short fiction, essays, screenplays, a mountaineering memoir by Edurne Pasaban, and Alejandro Saravia’s novel Red, Yellow and Green (forthcoming from Biblioasis, 2016), winner of 2016 Translation Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts. Awarded a 2016 Gabo Prize for Translation, Giménez is part of Montreal's collective The Apostles Review and serves as Assistant Translation Editor for Drunken Boat.

•

Notes:

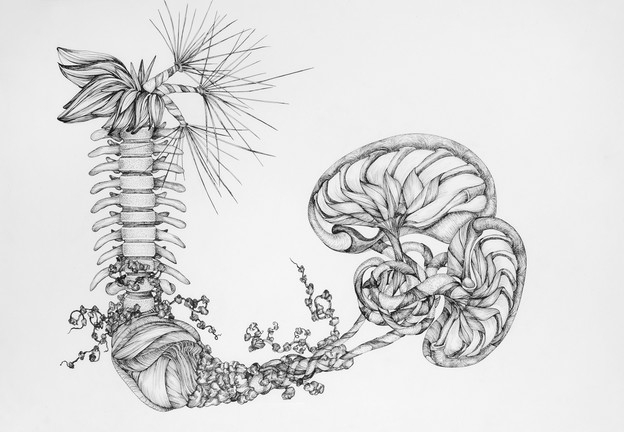

Maggie Nowinski. Abductions Series III: untitled Leviathan (2015) ink on paper. Used with permsission of the artist.

Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, "The Politics of Translation," Outside in the Teaching Machine (New York: Routledge, 1993), 180.

"How fossils are formed," The Nature of Prehistoric Life, Website of the BBC. Accessed May 10, 2016.

A poetics of the étrangère