Collaged correspondences: Alexa Mergen on movement, stillness, & other practices

When I was a girl, my father used to set me atop the postal service mailbox located around the corner from our house. Blue and red, with a cavernous mouth that swallowed envelopes into what I imagined to be an enormous steel belly, its steadfast presence signified a mysterious process of reception and delivery — the transport of words to somewhere else.

Of a related process — the carrying over of one word to another — poet and translator Forrest Gander observes a corresponding mystery:

It's a very mysterious process, translation. The translator must disappear into the original, must absorb the music of another's mind. And then the translator must return full force, with everything she has ever learned about the art itself — about poetry, if it is poetry she is translating. In its iterative obliterations and reincarnations, it's much more a spiritual than a transcriptional activity.

In those days, I would wait for our letter carrier on the front porch, ready to offer ice water in a tall plastic tumbler because summers in the Southern California landscape where I grew up could be scorching. In the house where I lived then and the house where I live now, envelopes were slipped through a slot in the front door — that threshold place where outside becomes in, where footsteps on the welcome mat prompt Chado's bark, and the knock of someone known sounds similar to the knock of a stranger.

threshold creatures at the door

In their phenomenological investigation of Otherness, contemporary philosophers Richard Kearney and Kascha Semonovitch describe potential scenarios hinged at the liminal: At such thresholds of experience, we stand in an event: an opening onto hospitality. But doors can be opened or shut. Or stand ajar. It may be unclear who or what moves first. The event might lead to a welcome kiss or a violent struggle. In either case, a volatile ambiguity awaits resolution into a particular meaning.

Beyond the physical doorway, thresholds might also define the limits of one culture and another, one political group and another. Since the start of the twenty-first century, it's reported that 7,000 mailboxes have been removed from U.S. sidewalks, partly because of electronic correspondence and online bill paying, partly because of fears of terrorism.

In the fifteen years that neighborhood mailboxes began disappearing, my friend Alexa Mergen has sent me letters postmarked up and down California: Santa Rosa, Joshua Tree, Bakersfield, Sacramento. These days, her posts typically arrive via in-box from her home in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, where she teaches yoga, writes, and, shares recipes for good things.

Alexa and I met in a course on Emily Dickinson, for whom letter writing was like breathing — constant and daily, something tied to living.

A letter is a joy of Earth —

It is denied the Gods —

To write a letter — slip it (folded) into an envelope, address it, and post — requires the movement not of an immortal but of a human, very much alive. And yet it's from letters that we also know the dead. And maybe something of the divine.

In the lexicon of Emily Dickinson, the word letter might mean any of the following:

A. Missive; epistle; printed text; communication made by visible characters from one person to another at a distance.

B. Verbal expression; [fig.] gift; souvenir; trinket of memory; token of affection.

C. Paper; correspondence; [fig.] good works.

D. Character; grapheme; alphabetic symbol; [fig.] word; writing; poem.

E. Statement; declaration; proclamation; announcement; calling card; [fig.] poem; prayer; inspired message.

F. Prayer; orison; communion with Deity; expression of praise and petition.

G. Secret note; billet doux; private document; written message from one's beloved

H. Post; missive; [fig.] invitation to visit; preliminary communique; preparatory text prior to a face-to-face meeting.

I. Warning; message; means of communication.

J. Revelation; prophecy; scripture; divine inscription; message from God

K. Receiving a written note; arrival of a posted correspondence; getting a piece of mail from a friend or loved one.

Within such an alphabet of possibility, how like a letter a poem is! Not identical, but similar, corresponding, for example, spirit with material, or time with distance. How each might carry — in each instance of transmission (and re-transmission) — infinite moments at once immediately present and forever unrecoverable. To arrive as if by telepathic electricity and connect without connectives, writes Susan Howe of Dickinson's envelope poems that arrive to us via The Gorgeous Nothings.

What might it mean to connect without connectives? More than fifty years before The Gorgeous Nothings connected the world to Dickinson's envelope writings, Jack Spicer posited this possibility of joinery: The reason for the difficulty of drawing a line between the poetry and prose in Emily Dickinson's letters may be that she did not wish such a line to be drawn.

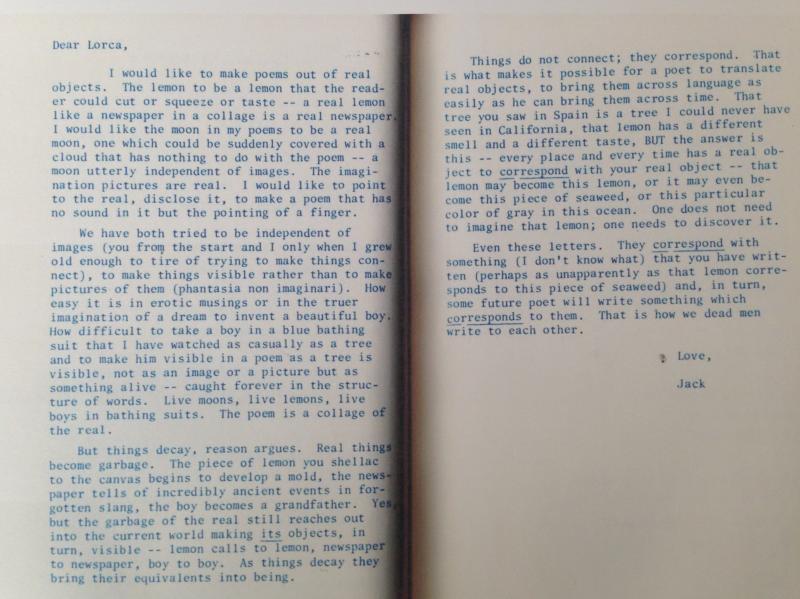

Soon after: Things do not connect; they correspond, writes Spicer to Federico García Lorca in a letter meant for anyone to see:

“Letter of Correspondences” from Jack Spicer’s After Lorca, 1957 | Cuneiform Press

Invoking this third letter from Spicer’s 1957 After Lorca, Anna Rosenwong posits translation itself as correspondence between artists across time, space, culture, and language. Such a “letter of correspondences” not only accurately describes the nonequivalence and connection in any act of translation or adaptation, writes Rosenwong, but also advocates for translation as a poetics of indeterminacy, where "that lemon corresponds to this piece of seaweed."

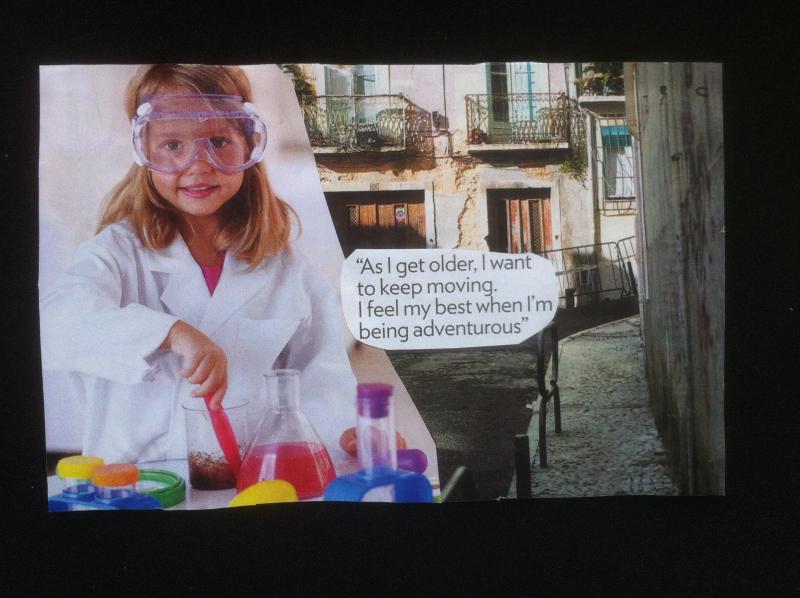

The correspondence of my friend arrives sometimes inside envelopes, sometimes upon handmade postcards, collaged with words and images:

"Keep Moving" collaged postcard by Alexa Mergen

Of such postcards, Mergen writes:

They were an attempt to make little visual poems through juxtaposition of advertisements clipped from magazine pages and pasted onto scratch cardboard (cracker boxes etc.), stuff that would usually be consumed and discarded. The cards themselves are dis-cards, not meant as art pieces but to fall apart, sometimes even in transit, so that what the receiver receives is a new statement tumbled through space and time.

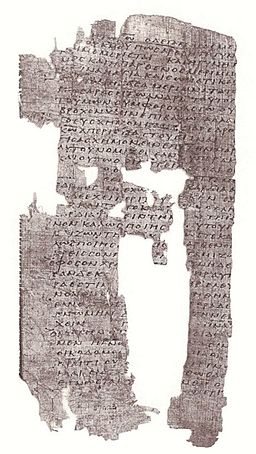

Among letters received through space and time, the First Epistle to the Corinthians might be one of the most tumbled. Attibuted to Paul the Apostle and containing several of the most widely relayed passages in the biblical canon, the letter’s text appears in manuscripts dating as early as the third century AD. One particularly known section — sometimes referred to as the tongues of men and angels verse — corresponds language, mystery, and ἀγάπη, what ancient Greeks knew as agape, and which is often translated into English as charity or love.

If I speak with the tongues of men and of angels, but do not have love, I have become a noisy gong or a clanging cymbal. If I have the gift of prophecy, and know all mysteries and all knowledge; and if I have all faith, so as to remove mountains, but do not have love, I am nothing. . . . Love bears all things, believes all things, hopes all things, endures all things.

Such is the mystery of enduring correspondences! The First Epistle fragment here is from the Oxyrhynchus Papyri, a group of manuscripts tumbling as far back as the first century AD and discovered in the late nineteenth century at an ancient rubbish dump.

Papyrus 15 – Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 1008, 1 Corinthians 7-8, 3rd century, Cairo Egyptian Museum

These days, correspondence arrives in a virtual instant, as if by telepathic electricity.

Long years | apart — can | make no | Breach a | second cannot | fill —

I think you whenever ED crosses my mind, my friend e-mails, which is often.

Poet and Dickinson scholar Michael Ryan notes that Dickinson's family owned nineteen Bibles and that she heard over fifteen hundred sermons by the time she was twenty-one. Given such a world, Dickinson was surely familiar with the biblical version of the ancient Corinthian letter, and yet she was one for whom worship didn’t necessarily correspond to conventional religion. From her lexicon:

worship, n. [OE weorðscipe.]

Vespers; hymn; psalm; evensong; evening rosary; solemn ritual; religious service; communion with the divine; [fig.] poem; creative work.

As Ryan points out: Poetry was prayer for Emily Dickson, especially the poems least like conventional prayers.

Some keep the Sabbath going to Church –

I keep it, staying at Home —

.....

So instead of getting to Heaven, at last —

I'm going, all along

Within such an arrangement of letters, how like the sublime language becomes, transporting ineffable future to present tense, divinity to daily dwelling. Small thresholds — crossed by way of a keyboard, papyrus, or penciled, folded and slipped into a pocket to join us with another place and time, another vision.

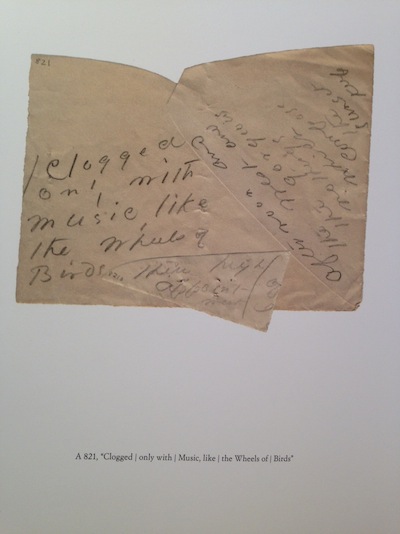

Transporting us with care through Dickinson's late manuscript miniatures, poet and textual scholar Marta Werner relays fragment A 821 as a sudden collage made of two sections of envelope:

Dickinson manuscript A 821 from The Gorgeous Nothings

The right wing slants upward into the west; the left, diagonally upward into the east. In the threshold place in between, writing rushes beyond the tear or terminus where the visible meets the invisible. . . .

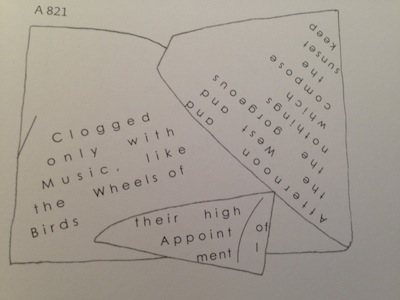

InDesign transcription of Dickinson manuscript A 821 from The Gorgeous Nothings

Corresponding with each of the 52 envelope-texts of The Gorgeous Nothings are type-set transcriptions, designed to mirror the shape of the original and placed en face, as if in a book of translations. In fact, poet and visual artist Jen Bervin characterizes these Century Gothic versions of Dickinson's missives as exactly that — a translation (not an imitation) of her scripts:

Dickinson's upper- and lower-case letterforms, punctuation, and markings are expressive and open to multiple readings. The typographic interpretations reflects our [Bervin and Werner's] scholarly engagement with her scribal practice but in no way claims definitiveness, given such ambiguities. . . . Ultimately, it was our hope to keep the transcriptions as legible as possible and gesture back toward the "bright Orthography" of Dickinson's manuscripts.

In the lexicography of Emily Dickinson, the word orthography might mean handwriting or properly written text, but it might also mean song, chant, bird call. In the case of The Gorgeous Nothings, it might mean a thing with feathers, a shared ultimate hope. Such might transcription of the physical arrive at translation of the spiritual — a crossing of the threshold.

The OED may forever list its definitions in numerical order, but among correspondences of multiplicity, ambiguity, and gesture, the verb translate might mean to make a version from one language (or form) of words into another at the very same time it carries or conveys to heaven without death.

Whenever my father lifted me onto that public mailbox, it was as if he were placing me keeper of the castle — into which we sometimes deposited letters of our own to be transported to another part of the kingdom. How they arrived into another's hands — their high appointment — remained a mysterious process, similar maybe to translation, similar maybe to love.

•

A conversation with Alexa Mergen

What projects are close to your heart these days?

Teaching others how the physical experience of yoga asana through time and space is a form of translation. That just as every choice a translator makes in sound, meaning and rhythm affects every other choice, every action a person makes, in body and thought, affects every other movement and feeling. Translating poetry literally showed me how everything connects within a whole. In yoga lessons, I create conditions for others to experience such awareness.

How did you come to be interested in translation?

In my teens, working at Blackistone Florist, a venerable shop near the White House, I practiced my school Spanish with coworkers from El Salvador. Being around native speakers was like adding color to the words I’d learned in black and white in the classroom.

Back in California, I worked as a school teacher and outreach worker with Spanish-speaking families. My employers asked me to translate the forms we used. I found that I liked the precision and responsibility inherent in the work.

Reading bilingual editions of Pablo Neruda’s poems frustrated me. Audacious, I thought I could do better. In graduate school, I studied some translations, as well as theory of translation, in order to make my own. Later, I picked up a Spanish language collection of Blas de Otero in a used bookstore. I wanted to crawl inside the lines, understand them from the inside out. Stephen Kessler encouraged my efforts and his own translations of Luis Cernuda inspired me. In Susan Kelly-DeWitt’s translation workshop I refined early attempts.

Where are some places you've wandered/traveled/voyaged, either in the real or in your imagination?

Stillness. I’ve explored stillness on the page, in poetry through sound and space, in prose by writing sounds that conjure silence; in places, from gym swimming pools to Sierra lakes, remote adobe churches to big city art museums; moving, from long solo road trips to the “quiet car” on Amtrak; on the yoga mat, holding a forward bend for minutes; in meditation, side-by-side with others in zazen; alone cross-legged on a garden bench. I’m researching the alliance between movement and stillness. Breath, body, relationship and words are my laboratories.

Is there a language you're drawn to, would like to know?

Classical Sanskrit! I recently completed a 14-hour course through the American Sanskrit Institute. The alphabet starts with the first vowel sound we make upon birth and ends with a final exhaled aspirate. You dig deep into the body to make the shapes of the words that travel along the paths of throat, palate, mouth, teeth and lips.

Would you like to share something here—a poem, translation, photograph, voice, image, map, snippet? Something you find crucial?

The postcard poems (pictured above) fit with what I love about the yoga teaching. The breath moves through one body in words and the other body creates shapes made in space, energy lines unseen yet existing, and soon dissolved. It's like translation in real time, like having a conversation. Or, as I was talking last night with Rev. Inryu at the zendo, a "practice encounter."

The poem below was published in The Poetry of Yoga. I started it in a workshop with Susan Kelly-DeWitt during a retreat in Georgetown, California. The setting was very physical, we wrote outside beside a pond I swam in daily.

Ink and Pen

Scratch sugar pine, smell vanilla.

Pull the honeysuckle blossom for

a bead of nectar. Smell. Taste your space.

Roots of redwoods, mangrove and tamarisk

extend under acres in an extensive handshake.

Tar is the swamp of city streets. The world

desires to absorb us. Crawl

from your doorway into wherever you are.

Don’t fear pebbles denting kneecaps, dry leaves

crushed beneath palms. Find mud. Be received.

Finally: “All translation should be followed by a blank page,” from Margaret Sayers Peden in The Craft of Translation, edited by John Biguenet and Rainer Schulte. In yoga speak, this would be: “Within each moment make space to receive the next.”

•

Alexa Mergen is a yoga teacher and writer. She makes her home in Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, and welcomes visitors online at Yoga Stanza.

•

Notes:

The Gorgeous Nothings: Emily Dickinson's Envelope Poems, edited by Jen Bervin and Marta Werner, preface by Susan Howe (New York: New Directions, 2013), 7, 14, 199-200, A 277, A 821.

The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson, edited by Thomas H. Johnson (Boston: Little, Brown & Company, 1961), #1639 (also found in Amherst Manuscript #730 as a fragment in a letter to Charles H. Clark; online at the Emily Dickinson Archive); #324 (#236 in R.W. Franklin; online at The Poetry Foundation).

Forrest Gander, quoted from “An Interview with Forrest Gander” by Michael Pagan, Coastlines Literary Magazine, Florida Atlantic University.

Richard Kearney and Kascha Semonovitch, Phenomenologies of the Stranger: Between Hostility and Hospitality (New York: Fordham University Press, 2011), 4.

Allison Marsh, “Postal Collection Mailboxes” Arago: People, Postage, and the Post, Smithsonian National Postal Museum, March 20, 2006.

Anna Rosenwong, “ ‘Le Bateau ivre’ and The Drunk Flotilla,” Western Humanities Review (Salt Lake City: University of Utah, Summer 2015), 69.1: 82. See also Joe Milutis, “Baudelaire’s ‘Correspondences’: An Introduction,” 37-39.

Michael Ryan, “Vocation According to Dickinson,” A Difficult Grace: On Poets, Poetry, and Writing (Athens: The University of Georgia Press, 2000), 161, 163.

Jack Spicer, After Lorca (San Francisco: White Rabbit, 1957) republished in My Vocabulary Did This to Me: The Collected Poetry of Jack Spicer, edited by Peter Gizzi and Kevin Killian (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press), 105-153. Online via Cunneiform Press.

In his introduction for My Vocabulary Did This to Me, Gizzi notes Spicer’s review of “the then-new three volume Johnson edition of the poems of Emily Dickinson for the Boston Public Library Quarterly” in which Spicer “points out the problem of distinguishing between Dickinson’s poems and letters. The significance of this finding would manifest itself dramatically a year later in his own poetry, After Lorca . . . and Admonitions (1958). In these works he developed his notion of correspondence and included letters as part of the overall scaffolding of the book. It is within these letters that he developed his concept of composition by book — by which he mean not a collection of poems but a community of poems that echo and reecho against each other to create resonances. As Spicer put it: [Poems] cannot live alone any more than we can.” xvii.

1 Corinthians 13. The translation here is from the New American Standard Bible, accessed online at Bible Gateway, which provides a multitude of versions in English and across languages.

A poetics of the étrangère