Copy/pasting the physical world

The bookworks of Ragnhildur Jóhanns

READING AS TOUCH

Icelandic artist Ragnhildur Jóhanns’ work exists in the liminal space between book and art, between reading and looking, but perhaps, most significantly, because much of her work is so tactile, between looking and touching.

But doesn’t the experience of reading books always involve touching? We touch with our eyes. We look with our fingers. Books are also anthologies of touch. Their bindings, pages, paper, print. Holding a book. Turning its pages. We feel the paper – its texture and thickness. As my niece once exclaimed, “Wow! Its pages are paper thin.”

When we engage with written language, we feel each curve or angle of letter. Some books are the size of a sparrow, some are eagle-sized.

READING AS AMBIENCE

In Jóhanns’ work, we examine text, reading the words, but also looking at them and not searching for each individual meaning or the relationships between them necessarily, but as a collection of words. A collection of tones and modalities of language.

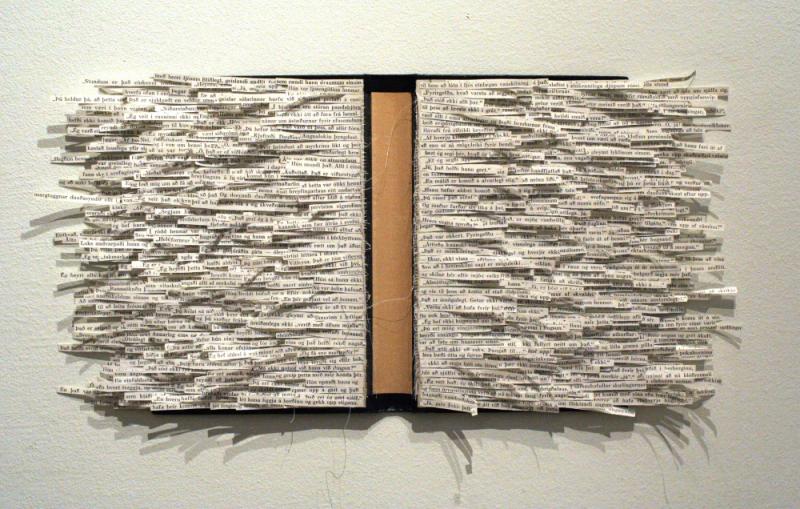

The little strips of paper drawing the voices out of the book—the crowd of words speaking. And like listening to a crowd—are they saying ‘watermelon, watermelon’ or reciting their own Ur Sonatas—we listen to the overall profile rather than the individual words. We don't listen to each cicada, but rather the swarm.

Meaning is ambient. Perhaps reading is ambient, also. We often read without really noticing. Words surround us, like leaves surround squirrels as they go about their daily leaps. (I think of a conversation I had with derek beaulieu about his notion of ‘ambient poetics,’ though I’m not sure if this is what he means.)

COPY/ PASTING THE PHYSICAL WORLD

Jóhanns’ bookworks often feature little strips of paper sprouting from the book, the words, like plants growing through cracks in the sidewalk, escaping, seeking the outside. Instead of “Copy/pasting” the digital representation of the words, the actual physical contents of the book were moved. We feel the tactility of the book. Its objectness.

What is the sum of a book, what is its content? Its paper, its lines, its words on paper and lines? Our usual notion of a book is that it is one imaginary long paper segmented then bundled into the separate sheets of the codex.

In Jóhanns’ work, the words on distant pages can speak to each other across pages like residents in an apartment building on their balconies looking up, looking down, passing grammar between them.

Jean Cocteau says, “The greatest masterpiece in literature is only a dictionary out of order. And what if that ‘out of order’ masterpiece were itself out of order? And what about the dictionary or the book considered as a form in itself, as a ‘masterpiece’ of its own? What happens if you take apart the book itself? When we read a book, we read so much beyond the words. So much beyond the grammar that the author presents.

WAITING FOR THE ELVES

I’m particularly intrigued by the presentation of these bookworks.

Framed photographs of images of books.

Photographs of treated books themselves pictured on a page within a book.

Shelves of books.

Videos of books, the extracted slips of paper rustling like grasses.

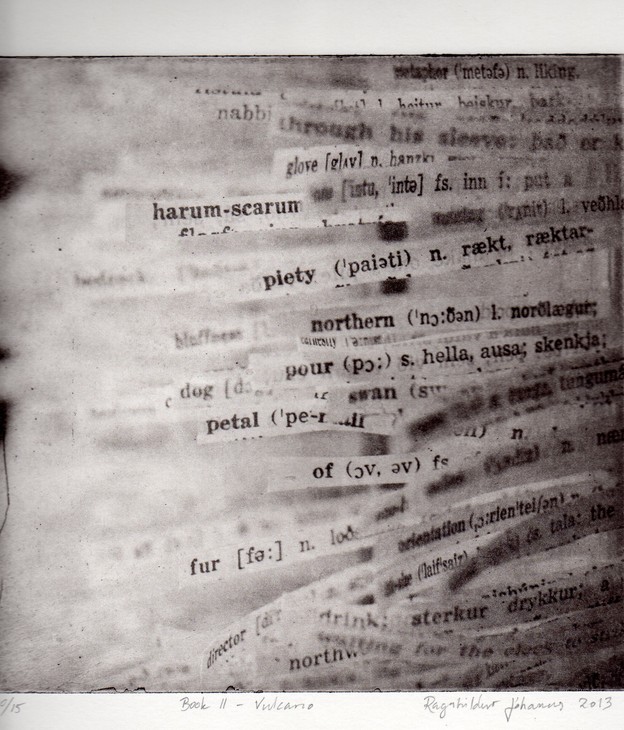

And in the image at the top of this post (Book II – Vulcano), the moody grey texture of the photography. A romantic image of a treated book. The gloaming light of reading. We don’t need Heathcliff glowering over the moor. We have this dictionary of English to Icelandic.

Northern. Fur. Petal. Piety. Harum-scarum. Through his sleeve. Glove. Pour.

æ ligatures and eths.

Does that say “waiting for the elves?”

And we can look things up on the internet:

Sterkur. Strong, as in strong coffee or alcohol. And this: “Sterka. You have strong arms, girl.”

*

GB: How do you imagine someone 'reading' your work? How would they engage with the text as text, or the relationship between the printed word and the book object? These texts are not collaged, but instead their usual relation to the page and to the book has been changed. They still are connected to their source: the book and page. And the texts have different kinds of belonging. To the source book, to the language, to the tradition of books. To the narratives or poems that they create together with the other fragments of texts.

RJ: I always like the fact that there is no narrative in these texts and it challenges the reader to find a different way to read. One of my most favorite parts about people reading my work is the fact that every reader reads a different story because they grasp a sentence here and there and make up a new feeling for the text.

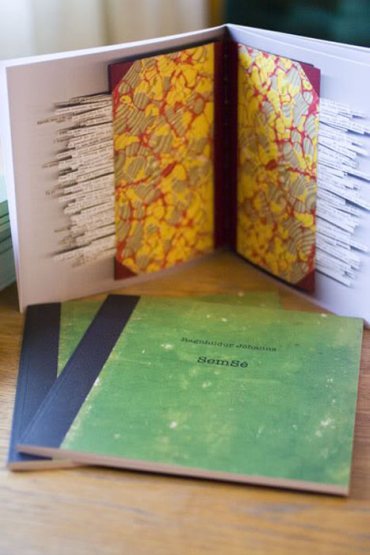

GB: These texts and the little blades of paper that they are printed on seem to me like they have grown from the books. Or that they are escaping. Or are they are somehow the books' (or the text’s or story's) auras, its energy. They bring out the sensory nature of the book as object. There is movement, rhythm, and tactility. They recontextualize words and printed material. The books become sculptures. They become three dimensional objects-in-the-world as opposed to books that can only be open or closed. And these altered books don't appear on shelves, but in galleries. (Unless, like in Semsé, the books appear in another book.)

How do think of these works in relationship with the traditional book and with the readers’ traditional engagement with reading a book?

RJ: I love the object book, it´s such a beautiful thing and since I was very young, I have read a lot so it has had a huge impact on me. I liked the idea of turning the books in a different way and making the text sort of like growing out of them because that is sort of what normal books can do for us who read. It´s also a way for me to make up a new poem and to transform old objects that are not wanted any more into something completely different. It might something like a homage to the book.

GB: How do the texture and design of the original book relate to the chosen text and to the 'readers' experience of your work? You seem to choose a particular kind of book—older books of a certain size. What are your thoughts about such books and the reader/viewer's experience with your work?

RJ: I started out with working with books that the owners didn´t want to have any more, so they were being thrown away, unwanted. At first I wasn´t thinking about the size that much but they do come in different standard sizes so they can easily be matched together.

What I was aiming for is to make a romantic poem out of the books and what interested me in this is the fact that you can pull out certain sentences and when you take them out of context you can make a new context and that means that whatever kind of a book you have this is still possible, even if the book is a children’s book, autobiography or a novel of whatever kind—they don´t have to be romantic novels for this to be possible. So what I try to create is this feeling of a romantic/erotic poem with carefully chosen words and sentences and form my experience [so] the reader gets this feeling.

More about Ragnhildur Jóhanns and images of her work can be found at her website.