Truth in the cage

The poetry of Mohammad Ali Maleki

Hello. im a refugee in the manus. but im not good speak english. im like poetry. I was writing 2 poetry. Are you help me writing poetry? My poetry farsi send australia edit change english come bake in the manus. are you help me to written poetry me?

April 1, 2016

The message arrived in my “other” Facebook folder, which I rarely checked. I didn’t know the author, a man I now call Brother, Iranian poet Mohammed Ali Maleki. He was — two years later still is — an asylum seeker detained by the Australian Government at the notorious Manus Island detention center in Papua New Guinea. Of the roughly 1,500 refugees who have been sent from Australia to Manus for offshore processing after fleeing their countries by boat since 2012, around seven hundred remain: many have been forcibly deported or accepted resettlement deals; only a handful have found safe haven in the US. The rest languish in the township of Lorengau, indefinitely awaiting their fate in “transit centers,” or adjusting to the fact that Manus is now their permanent home. All of which I knew very little about when I tentatively wrote back to Mohammad, unsure if he was who he claimed to be (it was Facebook, after all), what he might want, or whether I could help him.

Hi Mohammad, sorry it has taken me a while to get back to you. I am happy to help with your poetry. I have edited The Strong Sunflower for you. It’s a very sad and beautiful, but also hopeful, poem. Your English is already so good; I didn’t have to do too much. I just tried to take the essence of what you were saying and make it a little clearer for the English language. I hope you like it. Let me know what you think. Take care of yourself. Michele

April 25, 2016

Manus Island knew nothing of sunflowers

so I planted some seeds, from my heart, on Manus.

These seeds from a refugee, me,

grew into a flower for the Manus people

and the heat of the sun created new hope in their hearts …

This simple poem, written in Farsi, translated by fellow asylum seeker (and Mohammad’s good friend) Mansour Shoshtari, and sent via Facebook message on a smuggled iPhone, planted a seed in my heart and precipitated what would develop into a close friendship and working relationship; although Mohammad’s developing English and my nonexistent Farsi meant there were plenty of misunderstandings and miscommunications along the way.

Hell, im sorry little answer you. Thank you for editing. My English don’t well. This is my poetry send you. This is send farsi. And edit me … But my poetry don’t translet good into english.

Hi Mohammad. I don’t think I understand what you want me to do. I don’t know Farsi. But if you send me a poem you’ve written in English, then I can help you by editing it.

April 26, 2016

Working backwards and forwards with Mohammad to clarify his meaning and fine-tune his poems, I was — still am — constantly aware of my inadequacies as an editor. I worried about changing his words too much, but was always encouraged by Mohammad to trust myself as his “teacher” —although in truth he has become mine.

Hello, please say my hello to your family. I hope you are always happy and under the guard of God. We are used to these tortures and bad things that they did and are doing with us. And we have no choice to choose anything. Hope no one be in our shoe in the future in the world … My sister don’t worry. Maybe I could grow up in this hard time and harsh conditions. Some time my feeling bad, same time good, but I have to be hibet this station. I working on a poem. And writing my feeling.

May 26, 2017

Over the years, Mohammad’s poems have grown in complexity and changed in subject matter and tone. This is often a reflection of his degenerating and unpredictable circumstances.

At first there was hope:

Hope

There was a seed,

fresh and beautiful —

it knew nothing

of the outside world.

This beautiful seed

was stuck between

two walls in a village.

The sun and the moon,

the rain, the white snow

and the blue sky were unknown to it,

because this seed was living

in the dark.

Still, it had a good feeling

about the outside world.

It continued to say,

Behind this wall

there is something better.

Its heart beat

with each passing day,

beating faster and faster,

yearning to see the outside

until it couldn’t take it anymore!

Its heart cracked,

grew a stem

and then a bud.

Its pretty stem

punched the wall,

and shaking with fear,

poked its head out into the sun.

Afraid at first

it shrunk back into the wall,

not even knowing

it had seen the light.

But soon it grew restless

and returned, longingly, to look at the sky.

The sky rained on the bud

making it clean and cold,

then the sun warmed its body

inspiring the bud to keep growing

until it burst into a beautiful flower.

No one had ever seen such a flower!

But between the two walls,

standing steady,

the flower just said —

We can carry on,

in any circumstances.

All we need is patience.

An avid gardener, the green oasis Mohammad created outside his room was a source of solace and inspiration for him:

Tears of Stone

They brought me here forcibly.

I came to this land with no choice.

It doesn’t have rich soil —

They threw sulphur on the ground.

It’s true I am a stranger here; I have no one.

I can’t trust anyone

with my heartfelt words.

That’s why I created my garden.

They laughed at first, saying, It’s impossible!

because of the dry, sulphured soil.

But a single, beautiful tree grew in my sight.

A faraway, old tree …

Its bark was rotten

but it grew in good earth —

They threw no sulphur there.

I filled buckets with this soil,

pouring it onto my sad patch of land.

I did this for a many days;

I felt helpless, doing it on my own.

There was a big stone

on my dry land.

I tried, but couldn’t dig it out.

I left it, finally, where it was.

When I threw soil there

I would push it in with my hands,

smoothing it around the stone

until the ground grew level

and ready for seeds.

I asked many people

for seeds to plant in my garden.

They said, we can’t afford that!

You are a prisoner here,

we can’t give you seeds.

I had no hope.

A week passed …

While tending my garden

I saw that a bud had sprouted beside the stone —

I was so happy I kissed it!

But my bud was weak,

in need of water.

I asked God, what should I do?

God didn’t love me enough

to rain on my garden.

So I spoke to the bud

and told it not to grow hopeless —

An idea had come into my mind.

I sat by the bud’s side

recounting my bad memories

and weeping down onto its soil.

It was my task, every day,

to weep onto the bud.

It used to drink my tears:

we both had no choice.

One night, I went to cry for my bud.

I tried so hard but couldn’t weep.

The stone was my witness!

I wanted to give tears to the

bud but my eyes were dry.

What should I do now?

Suddenly, I heard a sound

and saw that the big stone in my garden

had a cleft right through its heart.

From the hard centre of the stone

a stream of water ran out!

From the source of this stone

my garden was flooded and fed.

My dear, sweet stone,

I will love you forever.

I wish many people

could learn from you.

I wish they could learn

as you did, how to soften

their hard hearts.

As time went on, however, and conditions on Manus worsened, Mohammad’s beautiful nature poetry gave way to more searing political indictments, and a tone of outrage crept into his work:

Truth in the Cage

You, who we came to seek refuge from,

why do you treat us so badly?

The world won’t always be the same.

Like a ball rotating for millennia,

it never stays the same.

Before you, many others had power;

now they no longer hold power.

Death, as a form of justice, is no escape.

In death, only goodness remains,

but evil will not be forgotten.

You, who say we are illiterate

and accuse us of being uneducated

terrorists — why do you judge us?

You call us whatever comes out of your mouth!

We brought three things with us when we were born:

discipline, mother wit and realisation.

You tried to take these away from us

but you couldn’t because they are congenital.

Realisation and mother wit aren’t related to literacy:

having these just means we are human.

If you see fault it’s because you’re looking

through the eyes of a wrongdoer.

You’ve taught us so many bad things here;

I hope God doesn’t forgive you for this.

You’ve taught people to become gamblers —

To keep busy they gamble day and night.

But we haven’t seen a winner, even once.

The gambler is always the loser.

You’re playing a bad gambling game with our lives.

Some people here have learnt how to smoke marijuana.

They’d never seen marijuana before!

Then you call these people addicted ones —

It’s you who’ve turned these people into addicts.

They use drugs to hide from their depression,

then you say — these people are sick!

Who made them sick?

Many have gone crazy in here. Why?

Because you put their minds under pressure.

Men become crazy because their minds can’t endure.

They spend their time talking with themselves.

You’re killing us, and then you call it policy!

You say — these people are imprudent.

But think, why are they imprudent?

A long time in detention has taken their wisdom away.

We’re unable to make right decisions now

because we can’t focus clearly enough to think.

It’s natural that this should happen, but not congenital.

Look how nervous, crazy and restless your guards are —

How can we possibly be calm in their presence?

Finally, you call us wrongdoers:

but it is you who brought us here illegally.

We didn’t know this place until you brought us here.

You’ve played with us all in different ways.

You’ve showed a bad face to the world:

but that isn’t our face.

The money and power are in your hands;

the law is in your hands.

I have nothing more to say to you.

Judge us by any means you like.

Be careful though, because what will you feel

when your time comes around?

Mohammad often worried that these more political poems would offend the Australian people; even affect his chance of settling in Australia.

Hello Michele seminara dear. Thank you for edited my poetry and makeing happy me. I hope people reading my poetry dont upset. I hope that you don’t face any problems because of my poems. I know that some people in Australia don’t like these kinds of poems. Im like all people Australia and world.

June 5, 2016

Mohammad also expressed concern for the safety of his family in Iran. Because of this, we didn’t share his work online under his real name for some time.

im writing poetry here but my gavermant in iran problem my family. I think don’t will writing poetry.

Oh no! You mean the government in Iran is making a problem for your family because you are writing poetry?

Yes.

How do they know about your poems? From Facebook?

Yes in iran they are chakein all people Facebook. I will close feacbook.

June 28, 2016

At one stage I lost contact with Mohammad altogether, as the departure of a doctor from the detention center meant his medication was withheld, causing him to slump into a depression lasting several months.

How are you going, my brother? How are things there?

Are you OK, Brother?

Brother? I hear things are very bad there at the moment. Are u ok?

Brother? Is your phone working? We miss you and worry about you.

February 9, 2017

Many of the men on Manus take medication because they suffer mental health issues related to past and present trauma, and the damaging effects of extended, indefinite detention.

My dear and precious michele. If me don’t writing anymore poem it because mansoor is very tired. And I need sometime to res. because I use pills and sometimes I really don’t know what I am doing or writing. I hope you understand what hard conditions and situations we are in. Thanks

Dear Mohammad, it’s hard for me to really know what bad things you are enduring. I know from what you tell me, but I can’t really understand it like you do. But I care about you, and like helping you as much as I can, even though it’s only a little bit. I wish I could do more. I hope you’re OK.

Dear, it’s enough for me that you edit my poems. I don’t like that you know more from here because it will leave bad effects on your mental and spiritual situation and may hurt you too. And I don’t want such things happen to you.

March 22, 2017

Not wanting to upset family or friends, writing poetry became Mohammad’s way of processing traumatic experiences, as well as witnessing on behalf of the other men:

Dream of Death

My dears, I know these are stories are old:

but please, I ask you, listen.

I was once young and happy, like you.

I used to jump from one wall to another —

I was so healthy and fresh.

I came to live in peace beside you.

I sought asylum because of my bad luck.

But for a long time now I’ve felt alone in this place,

terrorised by bad memories.

I don’t know why they tortured me,

why they cut my wings and feathers.

They treated us like animals, they put us in a cage —

What kind of help is that?

It’s as if they went to a feast and left us tied up,

like livestock, outside.

They played with my mind and soul for years.

They played as if I were a piece on a chessboard.

In the final moment of each game

I am always trapped.

I’ve lived with fear in this cage.

At night I have no peace because of nightmares.

The doctor said I had no choice:

so I took the mental pills he gave me

and sat by the fence, for hours …

And still I take those pills

and sit by the fence for hours.

At first my mind stops, then I dream.

My thoughts are killing me;

they take me to my death.

Suicide and self-immolation are always on people’s minds here.

Once this was just in our imaginations —

But do you see how all these dreams have now came true?

You all know what’s going on

in the Manus and Nauru hells.

There are rapes, burnings and hangings:

many have said goodbye to their lives.

Do you see what their mental pills do to us?

When you see or hear us, from far away,

you say, They’re crazy, stupid people!

Let me tell you, it’s all because of those pills;

it’s not our fault.

One day, like every day,

I took those pills: I had no choice.

I fell deep into a dream and was sunk there for hours …

In my dream I saw that I was dead.

They put me inside a rotten coffin

and shrouded me in pale, second-hand linens

taken from the rubbish.

When they wrapped me in those linens

my soul stepped apart —

I was suspended in air.

They were carrying me to the far corners of the cemetery.

I wished I could have died beside my parents,

died in peace, in their embrace.

I looked for a familiar person to hold my coffin

but there were only strangers, damning and cursing me.

They did not care for what they held;

they did not cry.

We came to the exiles’ cemetery

and they threw me into a hole with hate.

There was a stony pillow under my head.

The shrouded linens decayed on my body.

How terrible and frightening it was, inside the grave.

I saw many animals make their way into my grave.

My soul watched as they ate my body,

leaving nothing but fragments of bone.

Just yesterday I had talked and laughed

but now it looked as if I had never even been human!

They threw soil on my coffin;

they didn’t put a headstone there.

They wrote no name and no address.

No one in the world knew who I was.

In my dream I screamed, Parents! Know that I’ve died!

I saw my parents dressed in black, because of my death:

how deeply they cried out and wept.

Mum tore at her face until there was nothing

left undamaged and there were blood and tears

flowing down her face.

Her hair had already turned white from our separation,

even before my death. My father had begged,

Son, what kind of migration is this?

Now mum fainted from sorrow, sighing,

I have no sign of his grave!

And tears flowed from Dad’s eyelashes as he moaned,

It was our dream to see your wedding,

but we’ve heard of your death instead …

I woke in horror, the dream heavy on my heart,

wishing I had not hurt them by dying,

by failing to have that wedding day.

Understand, please: I wish to be healthy, like you;

to say goodbye to these damn pills.

For three years I’ve taken them and now I’m deeply

tired, hopeless and depressed.

How do I explain the hurt of this hard, bitter life?

I swear to God, every night I wish to die,

and every morning, I wish not to be alive.

Then, because my thoughts are killing me

I have no choice but to take these damn pills!

Should I thank your government for this?

Is this the care you give refugees?

That you make addicts here, and mental illness?

Only God can help us.

Put yourself in our families’ shoes for a moment.

Put your children in our shoes too.

If this is rudeness, please forgive me;

I make obeisance to you.

And I ask God to forgive those who torture us —

They know not what they do.

Sadly, untreated and often life-threatening physical ailments, abuse, mental health conditions, self-harm and suicide are an all-too-common part of life for refugees on Manus Island. It’s unclear how long anyone, including Mohammad, can hold on.

Brother

for Hamed Shamshiripour, who died by hanging on Manus Island

Brother, how quietly you abandoned us.

You left us alone, flew from our side.

You made us mourn from your death.

How cruel that tree was —

I want to cut it down at the roots.

You’re gone and the sun has turned pale.

The moon and stars have blanched too.

The sun, clouds and sky were above your head —

All of them witnessed your death.

The sky, sympathising with us,

has turned the clouds into rain and cries too.

It’s so hard to die in estrangement.

We all died with your death in estrangement.

We were condemned to die five years ago in this captivity.

We’ve witnessed the death of many friends here:

now you’ve died, but our turn is on its way.

In your dreams you saw how we were all burning.

How death made a flame and razed everything.

Brother, while dying in that moment,

many loved ones must have come before your eyes.

You must have wanted your parents to be beside you.

There was no one to even give you water —

I would have died to wet your dry lips.

What were you thinking about at the last moment?

Did you see your childhood?

Tell me: do you still feel pain in your body?

Do you still have pain in your neck?

We saw in the photo your neck was broken.

Did you see death dance with your eyes?

Youth’s freshness has faded from your face.

The freshness faded from your face.

The freshness of youth faded from your face —

How cruelly death whipped you.

Your shouts were in the air but we could not hear them.

You suffered so much in this life:

death was the end of your suffering.

Now the strong arms of the soil, the soil,

are hugging you.

WhenMohammad’s medication was at last reinstated and he returned to Facebook, and to writing, it was with a special force: he no longer appeared to worry about whether his words would cause offense. It seemed that the deaths and mistreatment of friends on Manus, and the ongoing duplicitous policies of the Australian Government, had ignited a fire in his belly. More than ever, Mohammad’s words shot from his pen with a power only the most extreme experience incites.

I dedicate this poem to the Manus detainees who lost their lives.

We have them all on our minds and will never forget them.

Expectations

Hey, Freedom.

You are not colour.

You are not smell.

You are not shadow.

You are not sunshine.

You are absolute darkness for me,

with no beginning or end.

In which part of the city can I find you?

If someday you pass though this city

put a red scarf round your neck

so we can recognize you.

I’ll sit on the train track

waiting for you to descend.

Hey, Freedom.

I don’t know what you are.

But I whisper your name like a lost child.

Freedom, set me free from this prison!

This prison made by fellow human beings.

Hey, Freedom,

I am a rain drop

waiting to join the sea.

Hey, Freedom,

look how my brain is frozen.

A spider web has surrounded my thoughts.

Smoke and dust sit on my mind;

my heart is surrounded by hatred.

They made a cage in my throat —

But they left my voice and enough breath to speak my truth.

If you come to this place someday

you will pass through a city of blood.

If you saw the blood on the ground here

you would never return, from fear.

We accept death just like life here:

we see no difference between water and blood.

Hey, Freedom,

tell me about windows that open to gardens.

Tell me about the singing of birds.

Tell me about the dancing of butterflies.

Tell me about the playing of fish.

Look how I forget these simple, everyday things!

Hey, Freedom,

I will not sit waiting for you.

You have killed my hope.

You have destroyed my goals.

You did not show mercy to my friends —

You led them to their deaths.

You made men sick by searching for you and killed them.

You hung and murdered others.

You pushed another into the river to drown.

You hit a stone on some poor man’s head and ended his life too.

Is this the meaning of freedom for you?

Hey, Freedom,

I’ve accepted my death here.

For years the ceiling of my room has been my sky.

Take my life and set me free.

I’m fed up with dying every single second.

Pour my blood into the veins of my country;

I don’t want my blood to dry inside my body.

I had hoped to see my mother again one day —

but the dandelions have told me she is dead.

Recently, conditions on Manus have taken another turn for the worst. The detention center, deemed illegal by the High Court of PNG, has been dismantled, but the men have not been granted any real freedom; instead, they’ve either been coerced to return home (too dangerous an option for most), told they must wait longer in transit centers to be resettled in a country other than Australia, or forced to accept a life of limbo living as “free” men in the poor communities of PNG.

Hello Michele seminara dear. Yes i was had interview and dont finished. Every day go to talking and they ask me. Im answer.

They are pressuring you to answer?

Yes i must answer.

What happens if you refuse?

I m dont refugees go to liveing manus. and am refugees im stay detention long time and tried go to other countery. I con not comeback my country. i don’t choice. They are decided me.

Both ways are bad for you.

Yes

July 20, 2017

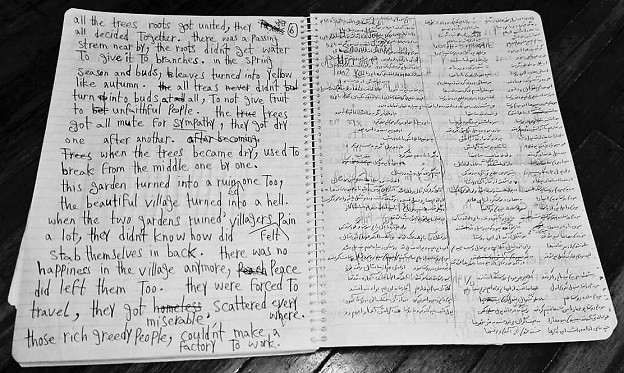

Realizing the Australian government was in effect washing its hands of them, in November 2017 the asylum seekers made a final stand, refusing to leave the demolished detention center. For three weeks the eyes of the world watched as they lived without water and food, until finally the men were forcibly removed. (Mohammad’s precious poetry notebook, in the care of his translator Mansour, was lost at this time, and his beloved garden was also destroyed.) While the Australian government can now officially claim there are no men left in detention on Manus Island, in truth, nothing has changed. As Mohammed told me: “they’ve just moved us from one prison to another.”

I asked Mohammad if he would grow another garden, but he is on the second floor of a building complex, and rarely leaves his room. Some of the local people are unhappy about having refugees offloaded into their already struggling communities, and acts of violence towards the men are common.

Words of an Unsafe City

These dark and narrow alleys,

how silent and sad.

Words are written in secret

in this unsafe city —

You read those words.

If you pass by them with neglect,

then within minutes, or even seconds,

these poems explode.

It’s a strange custom in this place,

the hurtful looks of the people.

Like the tick, tick, tick of the clock

it can shake your heart.

In the darkness of these nights

the hot weather turns to freezing.

I hear the stars sigh from the cold

and watch them fall

one after another

to the ground.

In my hand, a lantern …

Even in the light of day

I get lost in this city.

Searching for my misplaced life —

There’s no sign of it.

The whispers of dolls

sing in my ears like a storm:

their harrowing has confused

my mind.

Hanging from the wall

are three damn executioners —

clock hands counting my homelessness in years.

That clock determines

my death time in this village.

Beautiful flowers grow in this place

but the people are their enemies.

When I smell the flowers

their thorns push into my heart.

A lucky white bird is sitting on my shoulder.

I wish it could transport me far from here.

But the wind has stripped its feathers

and it can’t breathe freely —

Life’s cruelty has beheaded its song.

When you ask for the truth

no one here ever answers —

They’d rather shoot the question/er

instead.

Recently, Mohammad had a chapbook, Truth in the Cage, published by the small Australian Verity La and Rochford Street presses. I often contemplate how incredible this is, the strength of will of this man who was not, by his own admission, a poet when arriving in Australia, but who took to poetry — as many do — during the darkest time in his life; whose voice was quashed, but who found a way, sitting on a small Pacific island with nothing but an iPhone in his hand, to make contact with other writers and fashion a network of creative support and friendship; who taught himself to write and speak English; who has managed to have his poems published and even get a book out into the world. Surely the flowering of Mohammad’s poetry is no less miraculous than the sprouting of the seed in his poem “Hope,” which grew through a wall and pushed its head up into the light. One can only hope that for Mohammad and the other Manus men it’s as the poem says: “We can carry on, / in any circumstances. / All we need is patience.”

Silence Land

I have doubts about my sanity:

not everyone can bear this much.

They stole all my feelings;

there’s no wisdom left in my mind.

I am just a walking dead man.

I am just a walking dead man.

I yelled for help so many times —

No one on this earth took my hand.

Now I see many strange things

and imagine how the world would look

if it collapsed.

Perhaps it would be good for everything to return to the past;

for nothing to be seen in the sky or on the earth.

It would feel so good to be a child again

and go back to my mother’s womb.

For there to be no sign of me,

for me never to have gone mad in this place.

What if the woolen jacket I am wearing unravels

and begins to fall apart?

Or the butterfly flies back to its cocoon,

or the autumn leaf grows green

and returns to its branch on that old tree?

What if the tree becomes a seed in the soil?

I sound crazy speaking this way!

It’s the outcome of being detained for four years

after seeking asylum on the sea.

What if that sea returned to its source

and flowed back to the mouth of the river?

If that river receded back up into its spring?

If only the sun and the moon remained in the sky?

If I saw even the sun’s birth reversed,

watched it dissipate into space?

Witnessed the moon implode upon itself?

All things returning to their starting place …

How peacefull, to live in a colorless world,

everywhere silent and still.

Then the earth could be calm for a moment,

free of even one miscreant.

But what do you make of my vision —

am I sane or mad?

*

“The Strong Sunflower,” “Truth in the Cage,” and “I Dream of Death” were first published in Verity La.

“Hope” was first published in Rochford Street Review.

“Tears of Stone” was first published by the Red Room Company after being shortlisted for the 2016 New Shoots Poetry Prize and received Special Commendation for extraordinary work in extreme circumstances.

“Expectations” was first published in Other Terrain Journal.

“Silence Land” was first published in Bluepepper.

All the poems included in this article were written by Mohammad Ali Maleki, translated by Mansour Shoshtari, and edited by Michele Seminara.

Edited by Divya Victor