Leav Rupi alone

eXXXtreme #instapoetry

![“[O]ne ventures to guess that what Kaur is selling is not merely the neat, non-threatening lines of her poems, but her persona itself. In other words, Kaur the poet is Kaur the poetry.” Adaptation of a screenshot of Rupi Kaur’s Instragram feed, @rupikaur_.](https://jacket2.org/sites/jacket2.org/files/imagecache/wide_main_column/CalebWee_Tan_image.jpg)

A specter is haunting poetry. All the powers of prior poetic generations have entered into a holy alliance against them: lyric and language, conceptual and confessional, page and performance. It is the specter of social media, and the extreme popularity of the individuals who flourish on platforms such as Tumblr and Instagram, as well as off them. In and of themselves, young poets such as Rupi Kaur and Lang Leav who rise to prominence on social media with thousands of followers and readers are not unusual; one might even see the phenomenon as an inherent function of internet 2.0, with its emphasis on networking and user-generated content. What is unusual, however, is the spilling over of this prominence into the real world, so that Kaur and Leav have both seen their follower counts (2.8 million and 461 thousand at the time of writing) translate into bestselling sales: as Molly Fischer has observed, Kaur has sold nearly seven hundred thousand copies of her debut collection milk and honey, a figure which “beat out the next-best-selling work of poetry — The Odyssey — by a factor of ten.”[1] Much has thus been written about the giddy commercial success (and the formal inadequacies) of such poetry, but its etiology and stakes have rarely been examined. This article will therefore look at the reasons and the reactions to the extreme popularity of Instapoetry.

Kaur and Leav’s international presence is felt even here in Singapore, where their regional appeal is apparent. In July 2018, the poetry bestsellers of Books Kinokuniya Singapore listed Leav’s Sea of Strangers: Poetry & Prose and Kaur’s milk and honey in the two top spots respectively. Indeed, milk and honey was sold out on the site that month. Similarly, on local online Singaporean bookstore OpenTrolley, Kaur’s the sun and her flowers and milk and honey were listed first and second as poetry bestsellers at the time of writing. Perhaps it is not a coincidence that Kaur and Leav’s work are revered by and reverberate with local audiences. The literary output of Singapore is framed by anxieties surrounding identity tempered by a Sedition Act that criminalizes “promoting feelings of ill-will and hostility between different races or classes of the population of Singapore,” or “to bring into hatred or contempt or excite disaffection against the government,” which, when loosely interpreted, lends itself to a self-policing of discourse on race for fear of entering into the inflammatory. There is a will towards cosmopolitanism and “global appeal” that manifests often in linguistic tensions and insecurity, as echoed by previous Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong decrying the local variety of English as “broken,” “corrupt,” and “ungrammatical” in a speech in 1999.[2] Positioned in a wider neoliberal economic state,[3] the demand for readily consumable art that also touches briefly on — but never incises with — uncomfortable depth into questions of race, politics, or identity aligns well with how Kaur and Leav’s work is packaged. Of course, they have their detractors as well: at the Singapore Writers Festival in November last year, Simon Armitage described Kaur and Leav as examples of a brand of popular poetry which was “facile […] hollow, vacuous,” holding neither life nor language to account.[4] “I don’t mean to kick someone while they’re up,” said Armitage, “but what good can that kind of poetry do?” At that same panel, Rae Armantrout remarked wryly of Kaur’s pop-feminist poems: “it’s very good advice … but so is ‘eat your vegetables.’”[5] As Kazim Ali puts it in an article for Poetry Foundation in October 2017: “Rupi Kaur isn’t just Instagram-famous, she’s famous-famous.”[6] Famous enough, it seems, to warrant the snark — or “shade,” as the Instagram crowd might say — of established poets twice her age.

For fans of Kaur and Leav, the defense against Armantrout and Armitage’s criticisms is a reflexive one. It is all too easy to see these comments as emblematic of a generational gap between the baby-boomer poetic establishment and the new millennial upstarts, which renders the entire discourse around Instapoetry to date not dissimilar to Frank Sinatra’s dismissal of rock-and-roll music in the 1950s as “the most brutal, ugly, degenerate, vicious form of expression it has been my displeasure to hear,”[7] or the disdain that Theodor Adorno demonstrated in the ’60s towards the protest folk music of Joan Baez and Bob Dylan when he remarked that “the entire sphere of popular music [...] is to such a degree inseparable from past temperament, from consumption, from the cross-eyed transfixion with amusement, that attempts to outfit it with a new function remain entirely superficial.”[8] Kaur herself is far from the only poet of her generation to achieve prominence through social media: one might count as her contemporaries not only Lang Leav, but Nayyirah Waheed and R. M. Drake, all of whom have follower counts on social media numbering from the hundreds of thousands to the millions. These poets are distinguished from each other by perhaps more visual than formal cues. Kaur’s Instagram front page, for instance, faithfully alternates between photos or videos of herself, usually softly lit and professionally taken, and a black-and-white image of text in serif font, in short stanzas five to eleven lines long, rarely exceeding twenty lines.

These images of her poems are often accompanied by her own line drawings, which are, like her poetry, short and neatly fitting within the mediated space of the traditional square frame of the Instagram interface. As her self-portraits consistently take up half the real estate on her Instagram feed, a site where attention — and consequently space — is prime, one ventures to guess that what Kaur is selling is not merely the neat, nonthreatening lines of her poems, but her persona itself. In other words, Kaur the poet is Kaur the poetry.

This is the most distinct manner in which Kaur stands out from the other poets mentioned — Leav, for instance, alternates her poetry neatly, but with photographs of her newest book in various locations. Drake and Waheed are less curated: their posts frequently switch between fonts, lighting, and alignment. Waheed, indeed, takes photographs of the physical pages of her books herself, something that is almost never witnessed in Kaur’s online offerings.

However, intense, disciplined curation is evidently not a guarantee of Instagram success. Leav comes in with the smallest follower count of the four, even if her Instagram account is similarly curated to Kaur’s. This discrepancy between the two, coupled with Kaur’s self-presentation as both artist and art, begs the question of how Kaur constructs herself and negotiates her identities: not merely as poet, but also as feminist, minority figure, and celebrity. In press interviews promoting her second book and Instagram posts documenting her tour of India, Kaur makes repeated reference to the “team” she is travelling with.[9] This connotation of thanking “the team” mimics the discourse of a Hollywood celebrity speaking to an adoring public at an awards ceremony and implies the existence of an entourage: a number of doting people tending to one’s needs, too countless to feasibly thank by name individually. This Instagram performance of celebrity glamor is reinforced by Kaur’s repeated references to “going on tour” and the photographs of herself at the Golden Globes, a strategy which seems to telegraph glamor, celebrity, and fame to anyone viewing her account.

It is difficult not to measure Kaur’s success or popularity in terms of social media statistics. Kaur’s work and social media presence are inextricable from each other; parallel to her popularity is her self-discourse of Rupi Kaur the poet as progressive, yet infinitely consumable. There is certainly a sense that Kaur positions herself within the zeitgeist: as the pop-feminist, self-love champion of her time. One of Kaur’s most popular poems, with 217,000 likes, reads:

it is a blessing

to be the color of earth

do you know how often

flowers confuse me for home

It is perhaps due to this extremely marketable approach that Kaur’s work is lauded as something “every woman needs to read” or “have on her nightstand or coffee table” by Erin Spencer in the Huffington Post.[10] In her review, Spencer praises Kaur’s work as “getting the hug you need on a rainy day,” which speaks to what people think the universal woman desires or needs in their life. The rhetoric of the soft and simple, restricted to “hugs” and books on the coffee table, is perhaps derived from (and contributes) to the discourse of what-women-want, which is also what Kaur continually negotiates, and often masters. To put it in more cynical terms, we might see Kaur’s feminism as not so much a stance she propagates through her celebrity as much as a means towards celebrity. Her first rise to prominence in the public consciousness came in 2015, when a photo of herself in pajamas she had uploaded to Instagram got flagged and deleted by Instagram. Kaur’s response, as the blog Jezebel noted approvingly, was to exhort her followers to “share the photo on whatever social media platform.”[11]

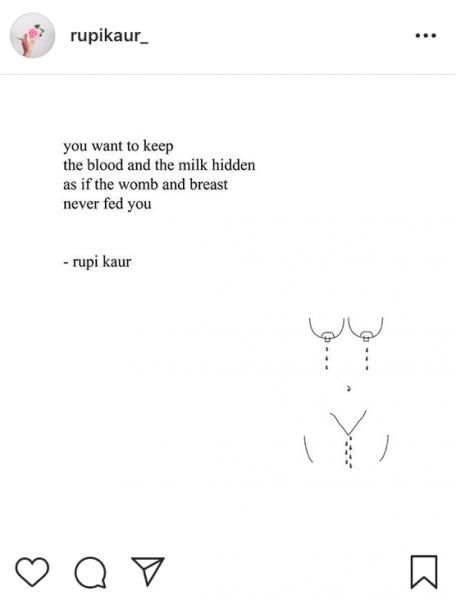

To that extent, Kaur can be seen as actively constructing herself as a spokesperson for women, women’s trauma, and the South Asian diaspora, by alluding to themes such as the taboo of visible breastfeeding and menstruation (“you want to keep / the blood and the milk hidden / as if the womb and breast / never fed you”).

This poem in particular is Kaur’s protest against the imperative to keep these bodily functions private. Nonetheless, the poem adheres to her usual aesthetic treatment of the piece, coupled with a line drawing of breasts facing downwards and a minimalist V to represent the vagina. Tiny, neat droplets fall from each nipple and the V in straight lines. Much like her poetry, Kaur’s drawing alludes to a theme that seems important to be articulated, but the tininess and neatness of her Instagram-formatted posts less articulate than mention it cursorily. This tiny neatness is what fuels her construction as infinitely consumable by the masses — even when engaging with themes such as sexual assault, racism, or bodily functions, the engagement is accomplished in an unobtrusive, inoffensive manner that never risks truly offending her Instagram followers. Chiara Giovanni’s criticism of Kaur’s work thus stems from this. In her Buzzfeed article, “The Problem with Rupi Kaur’s Poetry,” Giovanni takes issue with why Kaur’s poetry has mass appeal, and its necessary allusions to “unspecified collective trauma.” She states, “While Kaur didn’t answer multiple requests for comment, the FAQ section of her website indicates that she is interested less in sharing her own experiences, despite the claims of her fans, and more in what she portrays as the collective nature of sexual trauma in her community.” Kaur’s poetry, in minimizing differences and offense and in maximizing generalizability to women, creates her mass appeal. Her infinite consumability is both strategy and reason for critique.

To a large extent, Rupi Kaur’s visibility as a public figure has rendered her a Rorschach test of sorts: regardless of whether one supports or critiques her, the comments which result are inevitably more telling about one’s own poetics and beliefs than about the actual poems that are presented. Inverting Armitage’s dismissal of “popular poetry” as “facile […]vacuous, hollow,” for instance, we may infer that Armitage demands from poetry a necessary maturity, a necessary center. We might observe that Armitage sees poetry as essentially fulfilling a mimetic function that is not necessarily given to ideological concerns; rather, he is interested more in an engagement with experience that accomplishes the typically lyric task of “interrogating life and language.” Armantrout’s oeuvre-long commitment to experimentation, on the other hand, reveals itself in her dismissal of Kaur’s work for being trite on the same level as “eat your vegetables”: tellingly, the Language writer is far more interested in the construction of normative phrases and its dispersal through society than in the lyric persona of the poet. Implicit in Armantrout’s statement of preference for “poetry that takes [her] to a strange place” is an accusation of Kaur’s work as pedestrian and banal. Yet Kaur is able to fulfill this role to the poetry establishment: a threatening young upstart to all, regardless of their poetics, Kaur galvanizes and makes unlikely allies out of otherwise-opposed poets. On any other day, Armitage and Armantrout might have found themselves sparring over the Yorkshireman’s vocal dismissal at the same event of inaccessible North American poetry which has “imploded into the universities […] where poets talk only to each other and a coterie of critics.”[12] Instead, Kaur — even in absence — became the talking point of the panel, an odd phenomenon which reached its peak when Armantrout revealed that she had written a poem in response to Kaur’s work (a practice known in hip-hop as “beefing,” or “dropping a diss track.”) Here is the poem in question:

“Fall / in love / with your solitude.”

says the Instagram poet

with 1.6 million

followers.

Maybe it was

“Eat your hunger.”

*

You’re “excited to see”

how you will withstand

the coming cold and dark.

*

To withstand.

To hang around.

to hang around

with.

To withdraw.

To wither.

*

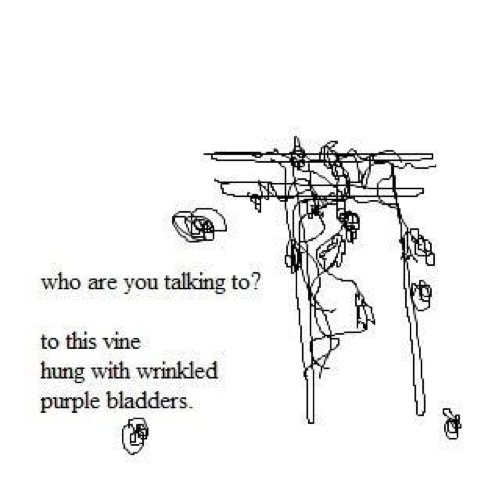

“Who are you talking to?”

*

To this vine

hung with wrinkled

purple bladders.

What is striking about Armantrout’s poem, on first glance, is the visual similarity between Armantrout’s and Kaur’s styles — a similarity Armantrout appears to be exploiting throughout the piece. Both poets favor short, terse lines, enjambed at a deliberate pace. In Kaur’s case, her verses typically stretch out a single bite-sized thought across the length of a stanza. One recent poem from her Instagram, for instance, reads:

our work should equip

the next generation of women

to outdo us in every field

this is the legacy we’ll leave behind.

One is struck with the suspicion that the entire sentence could be represented as a tweet without significant loss of meaning. Within the universe of her own poetics, on the other hand, Armantrout’s brief, compressed verses have the effect of forcing the reader into a close encounter with the banalities of commonplace language, her lines typically breaking on the turn between ideas to affect that dislocated strangeness she has professed to seek in poetry.

“Hung” thus opens on a quotation from Kaur: “fall / in love / with your solitude.” This use of slashes is significant: Armantrout habitually employs quotations within her work as a way of interrogating the expression of received societal ideas in the larger landscape of late capitalism, and this act alone is enough to suggest Armantrout’s stance towards the quoted work. Reconfigured as the starting line of “Hung,” Kaur’s poem is stripped of its enjambment, with only the slashes left to gesture towards the segmentivity of its original verse. Armantrout reminds us thus that although all texts might be fundamentally citational, quotation remains an act of power over the original text, a way of subverting and subjecting the quoted language to the formal logic of another’s poesis. Forced into a single horizontal line, what remains is the inherent paradox upon which Kaur’s poem rests: the glib contradiction between the encounter with alterity that is “falling in love” and the fundamentally solipsistic condition of “solitude,” which Armantrout relentlessly exposes by recasting the platitude as “Eat your hunger.” Armantrout further deconstructs Kaur’s poem by pointing out its contextual irony: that Kaur champions solitude on a social media platform which is “1.6 million/followers” strong. The following quotation is harder to identify: “Excited to see” is a commonplace enough phrase that it could have been plucked from any conversation or discourse, but in this context, framed by the earlier stanza, it suggests a prelude — perhaps an Instagram post — publicizing an upcoming social event that Kaur might be “excited to see” all her fans at; Armantrout swiftly undercuts this after the line break with her image of “the coming cold and dark.” The next stanza sees the poem vamping, jazz-like, upon the permutative possibilities branching out from the word “with”: as a counterpoint to the themes of solitude and sociality present in the earlier stanzas, “with” might alternately suggest relationship or accompaniment in its prepositional form (“to hang around / with” [emphasis added]), or opposition and separation in its prefix function (“to withstand […] to withdraw / to wither”). The final stanza closes upon a self-deprecating image: of Armantrout herself ruefully contemplating her own limited reach as a poet, speaking solipsistically only to a “vine / hung with wrinkled / purple bladders,” with the implications of age and obsolescence so transparent as to signal a certain parodic tone.

Fittingly for the Language writer, a slippage of language in her final stanza betrays the complexities of the situation. Armantrout might have desired to cast herself in the role of the obsolete avant-garde poet with a limited audience, but her unknowing (or perhaps she is more hip than she lets on) allusion to the popular social media app Vine reminds us that her audience is much larger than the poem itself might suggest. Certainly, no poem recited at a prestigious literary festival at which the poet is a featured speaker can be said to be disprivileged. What we are left with is a picture of stacked binaries: the old versus the new, the internet versus the page, prestige versus pop, boomer versus millennial. For Kazim Ali, though, Kaur’s work represents not so much the oncoming future, but a reactionary return to the old problematics of mainstream twentieth-century poetry. Ali maps Kaur’s “instafame” through acknowledging her “immensity” of audience, and states that he is, superficially, “all right with a young woman of color putting the canon of Western civilization off its pedestal for once.” He recognizes that poetry, however “simplistic” (as a matter of craft, not of intention or subject matter), is resonant with a wide and deep audience, while the notion of audience and writer has undergone radical transformation in contemporary times. Ali goes on to argue, though, that Kaur’s work nonetheless squanders the true experimental potential of the internet for a “poetry of brevity […] that utilizes the instantaneousness of the internet, its nonlinearity, potential for multiplicity of viewpoint and voice.” Most penetratingly, he notes that “against these modes of futurity,” Kaur’s work returns to a “singularity of selfhood, back to a romantic, heroic ideal.”[13] Seen this way, might we venture to see Kaur’s work as the extreme outcome of a certain poetic inbreeding, a ruthless genetic corruption of “the delicate lyric of self-expression and direct speech” that Perloff decries. Perhaps Rupi Kaur is less the product of tech-fuelled millennial narcissism than the inevitable progeny of self-satisfied bougie poetics. One must certainly ask why the emergence of a mass-market pop poetry is somehow more threatening than the neoliberal establishment economics of the current poetry institution. Back at the turn of the millennium, when Perloff borrowed the words of Ron Silliman and Charles Bernstein to decry the “simple ego psychology” of “a poetry primarily of personal communication, flowing freely from the inside with the words of a natural rhythm of life,”[14] one would have been hard-pressed to imagine a parodic version of that poetry more extreme in its kitsch simplicity than Kaur’s work. Yet the conspicuous lack of irony is precisely the point which a glib reading of Kaur-as-satirist would miss. Kaur’s success and her immunity to parody perhaps signal the arrival of a certain singularity which corresponds to the manner our contemporary world has tipped over into absurdity at large, with the goings-on of global politics now outstripping the imagination of parodists on a daily basis. Here, at the event horizon of a neoliberal globe, reality and parody no longer function as mutually exclusive signifiers. Kaur’s success thus demonstrates the extent to which poetry has been monetized and co-opted into the neoliberal system — both as an institution and as a genre — as well as the extent to which the commodified image of the artist is rendered easily consumable. Perhaps what the “narcissistic millennial” narrative misses, then, is the acknowledgement that the conditions for this brand of poetry have always been present and simmering; that this is, in fact, the extreme end of the path the baby boomers started the world on back in thetwentieth century, at the beginning of the neoliberal resurgence. By extension, any critique of Kaur which fails to self-reflexively address the calcified imbalances of the current literary world is therefore incomplete — to fashion Kaur into savior to revere, or scapegoat to be crucified, would be to miss the entire ocean for the wave she is riding.

1. Molly Fischer, “The Instagram Poet Outselling Homer Ten to One,” The Cut, October 3, 2017.

2. Goh Chok Tong, Singapore Government Press Release, Media Division, Ministry of Information and the Arts, August 29, 1999.

3. Eugene Dili Liow, “The Neoliberal-Developmental State: Singapore as Case Study,” Critical Sociology 38, no. 2 (March 2012): 241–64.

4. Simon Armitage, qtd. in Sing Lit Station liveblog of “Being One / Being Many,” discussion with Rae Armantrout moderated by Paul Tan, Singapore Writers Festival, November 5, 2017.

5. Armantrout, qtd. in Sing Lit Station liveblog of “Being One / Being Many.”

6. Kazim Ali, “On Instafame & Reading Rupi Kaur,” Poetry Foundation, October 23, 2017.

7. “Sinatra Blasts At Rock ’n’ Roll,” Trenton Evening Times, October 28, 1957.

8. Theodor Adorno, “Theodor Adorno on Popular Music and Protest,” Internet Archive.

9. Samuel Fishwick, “Rupi Kaur: ‘I’ve never been more aware of my colour,’” Esquire Go London, May 5, 2017; Ella Ceron, “Rupi Kaur Talks ‘The Sun and Her Flowers’ and How She Handles Social Media’s Response to Her Work,” Teen Vogue, October 4, 2017.

10. Erin Spencer, “Rupi Kaur: The Poet Every Woman Needs to Read,” The Huffington Post, January 22, 2015.

11. Jia Tolentino, “Your Beautiful, Feminine Period Stains Are Against Instagram Guidelines,” Jezebel, March 27, 2015.

12. Armitage, qtd. in Sing Lit Station liveblog of “Being One / Being Many.”

14. Marjorie Perloff, “Language Poetry and the Lyric Subject: Ron Silliman’s Albany, Susan Howe’s Buffalo,” Critical Inquiry 25, no. 3 (1999): 405–34.

Edited by Divya Victor