Handle with care

A study in (poetic) fragility

I think of feminism as a fragile archive, a body assembled from shattering, from splattering, an archive whose fragility gives us responsibility: to take care. — Sara Ahmed[1]

And with such force in their fragility; a fragility, a vulnerability, equal to their incomparable intensity. — Hélène Cixous[2]

get out the letraset and a blank page. rub on an M. rotate page. rub on an X. rotate page. rub on a g. rotate page. rub on a line using a border. rotate page. think that y should maybe have been an A but then do it anyway. lament half-rubbed on letter until i own it as part of the thing. rotate page. rub on a J but make its tail kiss an i.

a shape emerges. it looks like a clitoris, i think to myself. this thing is small, doesn’t take up too much space or just enough to know it’s there. you can always add more and can’t take less but the wisdom’s in knowing when to stop.

a slip of the wrist, and a seemingly emboldened y becomes a fractured v.

Language itself is extremely dialectic: fragile and subject to disruption, it fractures under pressure and the wear and tear of use; on the contrary, it also evolves and mutates according to its environment, showing resilience. But what happens when one accepts fragility as a condition of resilience and as a material condition of poetic production? What follows is a personal, creative, and critical exploration into the depths of material and psychic frailty in poetic practice. Vulnerability, as a condition from which and with which to create, can allow for a greater openness to and engagement with the world and the conditions that shape it. Here is a journey of writing in and through a learned fragility — one that unravels an intimate process of becoming, of moving towards, of intimate refusal.

For the last couple years, I’ve been using letraset — an archaic, outdated lettering technology — to create visual poetry in the form of linguistic collages, sometimes composed of nothing but letters, sometimes incorporating accompanying images. From these collages, and through the process of creating them — in the tedious shattering, the precarious yet intimate hand to page contact — a poetics of vulnerability and refusal (vulnerability in refusal) surfaces.

Letraset emerged in the 1960s (and was popular up until the 1980s) as the first branded form of “instant lettering,” a dry transfer printing process that was an alternative to letterpress typesetting and the prototype for computer desktop design and word processing. “No talent needed,” boasts one early advertisement, “just rub it down … and you can practically print on anything!” No skill was required, and yet when done correctly, the result rivaled the best printing methods available at the time. The technology brought professionalism and exactness to advertising and the arts, all the while still maintaining an organic connection between the hand and the material process.

I am certainly not the first to use letraset as a poetic and artistic medium. Jewish wartime refugee Mira Schendel’s carefully layered panes of rice paper covered in dry transfer collage, where the letters appear pristinely englassed, trapped in amber, are exemplary of the limitations and liberations of the medium. Calgary poet derek beaulieu also uses letraset in visual collage, and has created a letraset poetic based on stamina and longevity (his new work, in progress, is a visual poem three feet in width and sixteen feet in length).

Letraset’s rarity and fragility give it a transient quality; coupled with the intimate hand to page contact of its application, the medium itself challenges the masculinist impulse for permanence, immortalization, and enduring legacy in poetics and makes room for vulnerability and even grief. In resisting the creation of a permanent record in favor of a broken, fugitive archive, letraset poetics showcases a dialectic of vulnerability and/in strength, fragility and/in resistance. Like glass. In a solid state, strong and protective, yet delicate and prone, and when molten, extremely flexible and malleable. Capable of being shaped, cooled, back to strength.

Fragility as feminist praxis

trees do not survive storms by being rigid; rather, their strength lies in bending and giving to the winds. not a giving into, but a giving with. a strength disguised as frailty.

Fragility, as Sara Ahmed tells us, is a condition of received histories that can leave subjects, especially women, broken. However, in this common state, fragility becomes a glue for a feminist notion of community: “fragility itself is a thread, a connection, a fragile connection, between those things deemed breakable.”[3] In this way, Ahmed argues, fragility can be seen “not so much as the potential to lose something, fragility as loss, but as a quality of relations we acquire, or a quality of the building we build.”[4] It is this sense of building through and with fragility, using knots of language to bind these “acquired relations” together, that characterizes the practice of letraset poetics. Letraset comes like tools ready-to-hand: arranged by multiples, in rows on plastic sheets, they have the effect of being protolanguage but are awaiting function, purpose, connection. Once “assembled” or “built,” however, the letters take on a movement and meaning in alternative semantic mappings, where the entryways to meaning are many and imminently occurring:

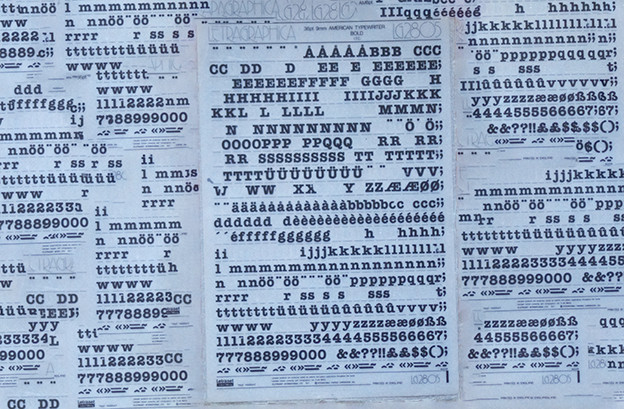

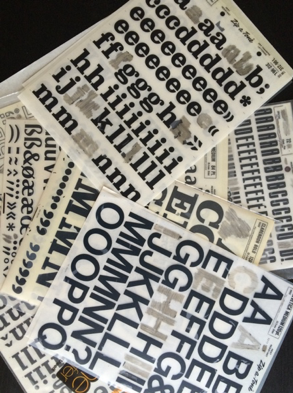

In the first image, the letraset appears in its “raw” state — neatly ordered, alphabetically, with the ghosts of flown letters forming interstitial gaps. In the second image, these letters, wrest from the orders of sequence and gravity, connect in newly created knots. The letters appear fragmented, alienated from context, yet the connections between the letters suggest multiple semantic pathways through, between, and among.

As Cixous reminds us in my epigraph, for women, fragility possesses an “incomparable intensity.” As women, we have worn the shackles of hardened patriarchal systems — recalling Ahmed, they have embedded within us an archive of struggle and brokenness. But women have and continue to organize around this history, transforming their vulnerability into what Ahmed calls a “becoming-army” of feminist resistance:

Shattering: scattering.

What is shattered so often is scattered, strewn all over the place.

A history that is down, heavy, is also messy, strewn.

The fragments: an assembly. In pieces. Becoming army.[5]

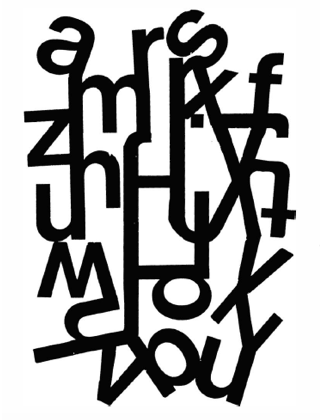

Shattered, shattering: a fragility signalling refusal. Working with letraset, itself a fragile medium, allows for a unique exploration of and revelry in shattering as poetic praxis. I’m interested in how letraset poetry can foster both connectivity and breakage from its constituent fragments — how it shatters, but also finds pathways through, systems of controlled language. Threaded through the fragmented dissonance of the collages is an active feminist semantic economy — one built on movement, energy, and an affect of strength and boldness:

On the page, the collages assume a veneered strength, but are, materially speaking, quite vulnerable and prone to damage. While appearing solid and durable, these works possess an underlying fragility that is “hidden” or “surprising” to the eye. This same hidden brokenness characterizes the experience of women and galvanizes them all the same. These poetic cartographies operate along a dialectic of concealment and reveal, mimicking the ways in which women’s boldness and strength — indeed, their unapologetic presence — are surprising in a patriarchal system that presumes to know and render their experiences fragile.

In her article on Ahmed’s work, Mahvish Ahmad highlights the correlation between fragility and structures of containment and oppression. “Unlike the brick walls of the master’s house in institutions of privilege and power,” Ahmad argues, “feminist dwellings must be built of a lighter material that give space for movement.”[6] So describes my poetic process of excising letters and images from organized systems — units of meaning floating, sometimes pushed into encounters with other letters and gestures of meaning, but estranged from a system that defines them indefinitely. These two collages represent the refusal of two separate but connected systems of control: language and patriarchy. Here, language is made a “lighter material” — unhinged from fixity, free to flow forth, exuberant, flippant, playful. While at once resisting semantic coherence and closure, these works also suggest the shimmerings of a “becoming army” of alternative feminine codes made from the broken pieces of language and coded feminine sexuality — forming a pool of legs, lips, eyes, and breasts free floating in a fragmented “body politic” (its letters rearranged in collage).

on the page, redundancies, quasi-words, shadows and pieces of their former selves form a radical feminine lexicon — at once becoming, at once lost. something in the gap.

While the medium is fragile, it also allows me to plumb the extremes of language, from its own extremities — letters — and then to their own extremities — serifs, arcs, curls, shapes that flourish, bind, cohere, and, when frail, fragment. It also allows me to open a space of play for letters, adjusting the kerning between letters and fonts based on chance placements, surprising encounters, and decisions that erupt in imprecise stutters and murmurs — dense characters reeling from automatic hand swarm unto unutterable, unfettering forms — and from this fugue, a freedom emerges and an order surfaces, an organic, intuitive geometry, in the intimate friction between textual and visual rhetoric. A sensual and felt corporeality activating the void between hand and page, letter and word, word and meaning.

Frailty and extreme intimacy

gold melts at 1093 degrees celsius. glass becomes liquid at 130 kelvin. paper and ink will be eaten by the sun in a matter of millennia.

While letraset poetics makes room for play, it also creates space for vulnerability, intimacy, and grief. The process of applying letraset is an intimate act — the hand to page process is a tactile labor borne from the delicacy of the medium and the choices that must be made by manipulating the material and the page. Unlike technological methods some poets use to create collages, such as computer programs or even typewriters, letraset is organically kinetic and laborious. Through its labor, and through its expression, it is also an intimate encounter with language — the floating letters betray the movements and the moments before the consolidation into signification occurs. The letters form contingent, transient connections and disconnections in tangled, palimpsestic riot:

Although you “choose” the letters from the pages and place them where you like, the letraset ultimately holds a lot of authorial power due to its fragility. You may need that A to align properly with that V in order to form your desired shape, but because letraset is almost always vintage and dated, it can become dried, cracked, and brittle, and the transfer is hardly ever perfect as intended. These linguistic casualties — the broken limbs, jagged edges — create a type of poetic intimacy from the unstable material; I almost always have to eschew any sort of overall intention for a piece, because the result is very much determined by the process and the individual temperament of the letters. Every time I pick up the letraset, I get a lesson in patience, playing with error, letting go — letting go as poetic process.

Through the unstable magic of letraset, I learned my first lessons in precarity, longing, and vulnerability under a guise of strength and exactness. It’s a lesson in fragility I learned at an early age — the daughter of immigrants with a broken, traumatic past. My dad operated his own electrical small business to make ends meet. He used letraset to make things for his business — signs, labels, draft drawings. Since my dad had a lot of it laying around, letraset became one of the first mediums through which I explored and experimented with language as a material, malleable, creative form. I learned the value of patience and wonder, and how the two can complement each other. I would marvel at its “transfer” magic, the ease with which it was manipulated by my hand but the difficulty of it also.

Letraset will forever be synonymous with the quiet strength of my dad’s organizing, labeling, reaching for exactness, the simple comfort of knowing where something is, when the ground beneath him — and us — was often shaky and unsure. Growing up without parents, as a ward of the state (and all the abuses that experience entails), my dad learned early how to hide his vulnerability with a tough veneer. His precarious upbringing in a fractured family who escaped trauma in wartime Hungary, only to experience further fracture and trauma in Canada, resulted in a complicated relationship to trust, intimacy, and grief. He is a loving man, and at times extremely tender and vulnerable, but relationships for him can be difficult and strained. Finding things in common with him, things to do together, is thus always a treasure. Letraset is a relatively scarce medium, and the search has become intensely personal for me as a point of connection with my dad. My dad is my blind bidder at letraset auctions — he’s a really great eBayer and we bond over the thrill of the search for the next big lot of dry transfer lettering. To some this might seem trivial, but for me, it is an extremely intimate and meaningful connection over language, frail materials, and broken pasts with mended hearts. Perhaps, in rewriting my dad’s own letraset practice, I came into my own feminist praxis. Though he did not know it, with these sheets of transferable letters, my dad taught me not to hide fragility, but to feel through it, revel in it, open myself to it, render old and new wounds poetic, and make them sing. Strength in precarity and struggle: a becoming army.

Lessons in impermanence and grief

with my fingers i rub the smooth, curved fillets signaling strokes, loops, ears, spurs, tails, hooks, slabs with sharp corners, hairline, wedge. blunt and angular terminals. exaggerated or soft, weighted, the minor extremities that reach out for meaning.

a gruesome inventory.

My explorations into fragility then intensified when I took my poetics off the page, to experiment with letraset on other surfaces, other landscapes. I began to seek out things I found on solitary walks, or in my travels — things in nature that are, inevitably, subject to entropy and disintegration. Precious, delicate, fragile things like leaves, shells, the scorched husk of a once-rooted beach willow. Detritus. Skeletons left behind. Any meaning they had enjoyed in their previous life was now dulled, but in this vulnerable state, I see a vibrant potential to bear witness to meaning again, anew.

Beginning with decaying matter, I work nonheroically, nonepically, keeping my focus humble, careful to not ask too much of the thing. Like us, these objects are subject to deterioration, breakdown, and death. But yet, they are also active, crucial factors of continuity and regeneration in and for their environments — again, recalling Ahmed, the break that gives of itself, for itself, into something new and powerful. I write on these decaying, organic forms, juxtaposing these promises of a return to ash and dust with a highly artificial material, itself signalling death — the ashes of technology swept away by the winds of change.

the hardest part of writing on fallen leaves is overcoming the veins.

and what’s at stake? the presentness of grief and the past of forget.

til death and decay do us part.

The vulnerability of letraset as a medium made me want to explore its fragility further through these fragile found objects. There is an intense intimacy in writing on fragile things, because they themselves are so unforgiving. As my pencil rubs the brittle landscape of the leaf or shell, bending to it, there is an awkwardness that betrays a sense of deep appreciation for, and connection to, the minute intricacies of organic life. I picked up a few leaves on my way home one fall day, doubtful as to whether I could write on them. When I sat down to write, I did not have a planned poetic direction in mind — rather, I would let the object — the feel, look, affect of it — guide my words. I immediately began to think of grief — of the immense fragility and strength within the act of grieving, and the necessity of both as a dialectic of feeling:

Writing on organic matter (especially with an artificial medium like letraset) highlights the very artificiality of language and also the contingency of its use. Language as placed, as placemeant — as erasable, alterable, and itself subject to change. In this way, my poetics represents the opposite of Christian Bök’s Xenotext project — itself an extreme poetic praxis of poetic objects under pressure and fragility, but tending towards a desire for permanence, masculinized legacy, and recolonization par excellence. The Xenotext is an attempt to inscribe a living poetry using a “chemical alphabet,” with the hopes that it would withstand any hostile environment and thus, the poet’s work would continue to live on. By manipulating the code of DNA, Bök’s work imparts the fallacy of permanence upon organisms and language. As he writes:

I am, in effect, engineering a life-form so that it becomes not only a durable archive for storing a poem, but also an operant machine for writing a poem — one that can persist on the planet until the sun itself explodes.[7]

The lab team, under Bök’s direction, ensures that the proteins “fol[d] according to [his] projections and simulations.” But the act of inserting one’s words into a cell and making it respond — the language and act of implantation, displacement, and invasion — is, undoubtedly, a (white) masculinist code. It is precisely this arrogant pursuit of enduring generational legacy, despite changing environments, that underpins and fortifies the ongoing colonial project.

Against Bök’s sought-after permanence, I offer vulnerable transience as a space of openness, a space from which to work. Being vulnerable and open to change and grief, both materially and psychically in poetic practice, allows me to engage with the world in creative, unexpected ways. After a year or so of experimenting with the form and practice of letraset poetics, I now have an extensive fragile archive of paper and objects. Full disclosure: I’ve photographed some of my work so that it is publishable and can exist longer than the worldly version will allow; but the fragile and vulnerable originals are housed precariously within parchment. And what to make of this fragile archive? These meager monuments of personal and political struggle? Ahmed refers to such fragility as “the record of a life,” the shattered pieces and selves that form a fragmented, ephemeral, yet lasting narrative of grief and resistance.[8]

And so I sit with a blank page, bare driftwood, smooth emerald beach glass, an open frontier. I take my broken materials and set off, to landscapes unknown, to grief, to impermanence, letting go, letting this thing within me sing.

1. Sara Ahmed, “Out and About,” feministkilljoys, February 3, 2017.

2. Hélène Cixous, “The Laugh of the Medusa,” in Feminisms: An Anthology of Literary Theory and Criticism, ed. Robyn R. Warhol and Diane Price Herndl (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1997), 356.

3. Sara Ahmed, “Feminism and Fragility” (lecture, National Women’s Studies Association conference, Milwaukee, WI, November 13, 2015).

4. Sara Ahmed, “Queer Fragility,” feministkilljoys, April 21, 2016.

5. Sara Ahmed, “Fragility,” feministkilljoys, June 4, 2014.

6. Mahvish Ahmad, “On Feminism’s Fragile Army,” The New Inquiry, May 15, 2017.

7. Christian Bök, “The Xenotext Works,” Poetry Foundation, April 2, 2011.

8. Sara Ahmed, “Sara Ahmed: Notes from a Feminist Killjoy,” interview with Nishta J. Mehra, Guernica, July 17, 2017.

Edited by Divya Victor