What is poetry?

A review of 'What Is Poetry? (Just Kidding, I Know You Know)'

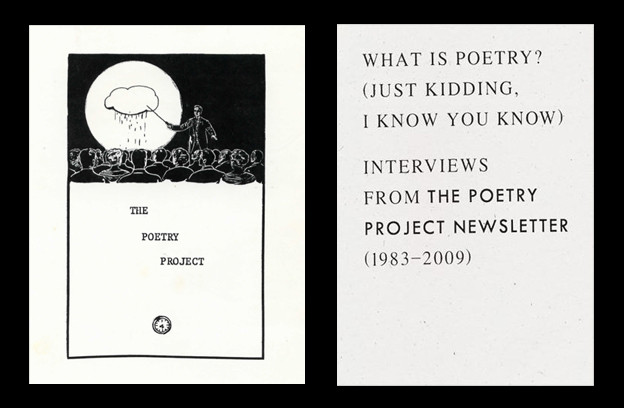

What Is Poetry? (Just Kidding, I Know You Know): Interviews from The Poetry Project Newsletter (1983–2009)

What Is Poetry? (Just Kidding, I Know You Know): Interviews from ‘The Poetry Project Newsletter’ (1983–2009)

Containing thirty-eight insightful and informative interviews with mostly innovative poets and a few non-poet fellow travelers, this big white book edited by Anselm Berrigan paints a clear picture of the Lower East Side avant-garde poetry scene. In these interviews, we are listening to the poets themselves, gaining an understanding of various avant-garde poetics straight from the horse’s mouth. The interviews matter because the poets interviewed matter — the poets are first-, second-, and third-generation New American poets and others poets aligned — but not always comfortably — with these groups; they are among the poets who have reshaped American poetry. The interviews are all drawn from the Poetry Project Newsletter, which started in 1972, basically as a calendar, and as the newsletter gets longer the interviews get longer. Some of the poets included in the interviews are Allen Ginsberg, David Henderson, Bernadette Mayer, Alice Notley, Renee Gladman, Fred Moten, Anne Waldman, Harryette Mullen, Ed Sanders, Kenneth Koch, Ron Padgett, Bruce Andrews, Ed Sanders, Ron Padgett, and Eileen Myles. I have included in this list black writers who are part of the Lower East Side scene and are included in this book, but who were in and out of the Poetry Project and other mostly white institutions and have, at times, created their own institutions. (More on them and their relationship with the white avant-garde a little later.) The book also includes interviews with people who are not poets, but who contributed to the scene through their work in other forms, such as art, theatre, film, and dance. If you want a full sense of this crucial scene, you need to read all the interviews. In short, if you care about post–World War II American experimental poetry, this book is a must.

It is only recently, perhaps, since I started living in New York and going to the Poetry Project, that I have come to understand the importance of the Poetry Project and the Lower East Side. In All Poets Welcome Daniel Kane observes: “While the West Village would generally remain a center for the avant-garde the first half of the twentieth century, the postwar era saw a gradual shift of the downtown artistic community toward the Lower East Side, particularly the section north of Houston Street and below Fourteenth Street, bounded by Fourth Avenue on the west and the East River on the east.”[1] Starting in the 1960s, the Lower East Side was a percolator for the American avant-garde — not just the poetry avant-garde — both in terms of individuals and institutions. Some of the institutions that sprang up were the Living Theatre, the Vision Festival, La MaMa Experimental Theater, and the Judson Church Poetry Theater. The figures included such luminaries as Sam Shepard, Amiri Baraka, Ishmael Reed, Merce Cunningham, Archie Shepp, and many others. Unfortunately, the Poetry Project is one of the few institutions still remaining; it is one of the key countercultural institutions where the reshaping took place and continues to take shape today. As Eileen Myles says of the Project in the December 14, 2016 issue of The Village Voice: “It stills burns and it still breathes.”[2]

The playful title of Berrigan’s book suggests not only the importance of poetics, but that it is always a collective, highly personal, undertaking. In the December 2016 Newsletter, he observes, “For some people that’s talking about composition and for other people that’s talking about sources; for others that’s talking about some combination of both. For some folks it’s about their life and moving over here and talking about their work and how that slides into allowing writing to happen.”[3] Or as Amiri Baraka declares in the pages of The New American Poetry: “I must be completely free to do just what I want, in the poem”[4] — that is, the new poetics conceives of poetry as an open field. Instead of basing their poetics on traditional practice, they base it on the avant-garde tradition of making it new and situating it in the local environment and the self. All these radical poetic schools are products of or influenced by the New American Poetry poetics and that was the aesthetic that the Poetry Project embodied and taught. Eileen Myles says: “I truly did grow to be a poet and intellectual here. I feel largely created by the city and the institution of the Poetry Project.”[5] And the black queer poet Renee Gladman observes: “I think that experimental writing is the perfect situation for people who have existed in this country on the margins. Because there is no narrative, there’s not an accepted narrative or a clear narrative of origin … I think that being a black dyke for instance makes that very complicated (presenting a cohesive person). It makes me feel very alien” (168–69). Moreover, the poetics is mostly oral. Allen Ginsberg declares, “I thought it was a united front against the academic poets to promote a vernacular revolution in American poetry beginning with spoken idiom against academic official complicated metaphor that had a logical structure derived from the study of Dante” (44). Lewis Warsh says: “I’m aiming for a fragmented narrative … I don’t want to create a ‘whole.’ The excitement for me is that I can include anything without thinking too hard about how it’s going to all add up” (245–46). Yet on the other hand, Will Alexander says: “The problem is that we don’t have a sustained society, but a truncated one, that moves from fragment to fragment . … What I think plagues the West is this whole idea of separation” (326–27). All of these poets are making it new but in their own highly distinctive ways.

Anne Waldman, former director of the Project, says of the institution of the Poetry Project, “I am interested in writers outside the mainstream, meaning those who work beyond careerism … [Waldman wants a place] where folk have an opportunity to gather and create some kind of oppositional or counter-poetics community. That was the original vision for The Poetry Project” (262–63). The creation of community is another theme. Even though the relationship between the Poetry Project, the Lower East Side, and black writers, especially in the early years, has been fraught, black individuals and groups, especially Umbra Poets, have been associated with the Project from its beginnings. In response to the question of the absence of black writers in the avant-garde community, Renee Gladman asserts: “I think it’s because the avant-garde has its origin among white writers. I don’t think that anything that has its origins in white culture is ever going to be suddenly diversified” (168). Some of the black writers who have been involved with the Project and are included in this book are Lorenzo Thomas, Fred Moten, Harryette Mullen, Will Alexander, Akilah Oliver, Renee Gladman, and Samuel Delany. It is unusual for an American artistic institution to be so fully integrated. To the list of virtually white avant-garde groups — such as Black Mountain, Beat Generation, New York School, the Language Poets — we must add the black groups, Umbra Poets, and Black Arts Movement; members of these black groups, especially during the early ’60s, spent a great deal of time on the Lower East Side. Even though the relationship has not always been easy between the black and white avant-gardes, they have learned from each other.

Another theme of the Project is collaboration. Anne Waldman says: “During the ’60s and ’70s collaborations were made possible by a particular bohemian lifestyle. You dropped in on painters at work, they dropped in on you” (211). Collaboration exists on many fronts beyond painting; you also have music, theater, film, and dance. Anne Waldman also observes: “Fundamentally, collaboration is a calling to work with and for others, in the service of something that transcends individual artistic ego and as such has to do with love, survival, and a conversation in which the terms of ‘language’ are multidimensional” (218).

I want to conclude with the interview with a couple — Bruce Andrews, a Language poet, and Sally Silvers, a postmodern dancer — because it shows the beauty of collaboration and is another example of how different genres feed into each other. The poet erica kaufman’s questions nicely focus the interview squarely on the topic. By and large, like kaufman, most of the interviewers in the book are well-informed and contribute to the high quality of the volume. Furthermore, in this interview, Andrews and Silvers have a gift for analytical history-based discourse, which helps us situate the entire avant-garde adventure. In New York in the late ’60s and early ’70s “we were both devotees of things going on in the experimental music scene, experimental theater scene, and whatever was around in dance that was interesting,” says Andrews. “I think our wanting to collaborate had to do with our involvement in these other scenes” (387). He continues, “coming to New York, and starting to write [in that time] … there was this tremendous heritage of experimental writing … a lot of it coming out of [John] Cage, of people like Jackson Mac Low, a lot of it coming out of concrete poetry, sound poetry, a lot of it coming out of the European Dada heritage” (400). In her dance theater Sally Silvers creates the movement and Andrews creates the sound to accompany that movement. She wanted to move away from formal dance and toward natural movement; she “thinks of herself as a movement choreographer” (399). She speaks of the influence of the Judson Church Theater dance experiments and where she has gone from there: “They were very interested in that with pedestrian movement and collaging and bringing things in from source materials. Being interested in the movement itself … I think what I am trying to add to it is some sort of sense of the social body” (398); she later notes a desire to “call attention to the body as a social presence” (391). Seeing the body as social jives with the political nature of the Poetry Project and much of the Lower East Side community in general. Andrews transferred his Language Poetry aesthetic to a sound/music aesthetic. He explains: “the thing that made it possible for me to make this music for Sally was that I already had a way of working with language that I could in a sense just transfer as an aesthetic or a methodology into sound. So I was already working with these small modular bits. … So, that was how I started working with music” (392). Together, drawing on the New York avant-garde heritage and the emerging scene, they forged new forms.

In these pages, we have the chance to explore the new creations and the thoughts behind those creations; we get to know the people behind the postwar avant-garde in New York; we get the chance to put voices if not faces to names we have heard for years from fellow poet friends; we get the chance to be introduced to a gallery of amazing characters, and we see them in their vitality, wit, eccentricity, and grandeur; we see them in quick detail, hear their plans, dreams, and projects. In short, we get insight, if not a total picture, of the New York avant-garde. Beyond individual actors we get to know a community and an institution. It is a complex story told in the in many first persons; even though it is incomplete, it tells us much. It is a great enterprise. Come onboard, you will enjoy it. These interviews help us clarify our understanding of important artists we know and introduce us to artists we might want to get to know.

1. Daniel Kane, All Poets Welcome: The Lower East Side Poetry Scene in the 1960s (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003), 2.

2. Eileen Myles, qtd. in Jennifer Krasinski, “The Poetry Project’s Half-Century of Dissent,” The Village Voice 61, no. 50 (December 14–20, 2016): 7.

3. Anselm Berrigan, “Anselm Berrigan interview about interviews,” interview with Betsy Fagin, The Poetry Project Newsletter, no. 249 (December 2016–January 2017): 21.

4. LeRoi Jones, “How You Sound??” in The New American Poetry, 1945–1960, ed. Donald Allen (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), 424.

5. Eileen Myles, “An interview with Eileen Myles by Greg Fuchs,” in What Is Poetry? (Just Kidding, I Know You Know): Interviews from The Poetry Project Newsletter (1983–2009), ed. Anselm Berrigan (Seattle: Wave Books, 2017), 378.