'Readers of the future' would be interested

Gary Lenhart on 'Public Access Poetry'

Note: Public Access Poetry was broadcast on Manhattan Cable TV from 1977 to 1978. The show was independently produced by a group of poets associated with the St. Mark’s Poetry Project — a team consisting of Greg Masters, Gary Lenhart, David Herz, Daniel Krakauer, Bob Rosenthal, Rochelle Kraut, and Didi Susan Dubelyew. It was recorded in the Metro Access/ETC studio on Twenty-Third Street and Lexington Avenue, and broadcast live on Channel D using airtime given over for municipal use by Time Warner Cable. The show featured readings and performances by “second-generation” New York School poets — including Ted Berrigan, Alice Notley, Ron Padgett, Bernadette Mayer, Lewis Warsh, Eileen Myles, Barbara Barg, Rose Lesniak, Steve Levine, Jim Brodey, Tim Dlugos, and Brad Gooch.[1]

The Public Access Poetry archive has only come to light relatively recently. Greg Masters had been storing the recordings on three-quarter-inch open reel videotapes in his East Village apartment. Lacking the now obsolete technical equipment required to play the tapes, they had remained unwatched for over thirty years. In 2010, Masters donated the archive to the Poetry Project, who were able to have the tapes digitally restored using a grant from the New York State Literary Presenters Technical Assistance Program.[2] In April 2011, selections from the tapes were screened at Anthology Film Archives, and in 2012 the Public Access Poetry archive became available online — hosted by PennSound, the University of Pennsylvania’s poetry website.

The following interview took place on December 14, 2011, and was revised in consultation with Gary Lenhart in August 2016. — Ben Olin

Ben Olin: Could you describe the beginnings of Public Access Poetry?

Gary Lenhart: I believe the program was conceived during a conversation between David Herz and Greg Masters. It was a time when Greg, Michael Scholnick, and I, as the editors of Mag City, saw each other almost daily, so I was quickly brought into the scheme.[3] There may have been another interlocutor who backed out when we got to specifics about money and time. Danny Krakauer was the other person to invest his money in the venture. I don’t know who had the idea of inviting Didi Susan Dubelyew to host the show, but none of the four collaborators felt up to appearing before the camera on a regular basis.

Olin: Did you conceive of Public Access Poetry as a platform for any particular literary scene or school of poetry?

Lenhart: It was definitely not a plan to showcase our work. But we were all part of a Lower East Side community where many poets resided. None of us had cable television, and I didn’t know anyone who did. But David convinced us there would be viewers, that producing the show would be cheap if we did the camerawork ourselves, and that we would assemble an archive of readings by the poets we enjoyed hearing. We began with Ted Berrigan, and our second or third reader was John Ashbery. But John must have been disappointed when he arrived at the studio, because he told us he was going across the street for a drink and didn’t return in condition to read.

Olin: How did you hear about the studio and broadcast facility?

Lenhart: David Herz knew about it. As noted above, he convinced the rest of us that someone would watch at the time, and I think we all believed that “readers of the future” would be interested.[4]

Olin: Where did you record the show?

Lenhart: For the first year or so we taped the broadcast in a studio on Twenty-Third Street near Lexington Avenue.[5] As rents rose there, the studio moved further downtown. Was it Rivington Street? From those studios it was no longer broadcast live.

Olin: Were you aware of other artists working with public access or video during this period? If so, were any particularly inspiring?

Lenhart: We were certainly aware of video artists, but I didn’t know much about TV. I had an old black-and-white TV for a matter of months, then loaned it to Jim Brodey, who kept it until his roommate grew angry with him and threw it, along with Greg Masters’s typewriter (which was also on loan to Jim), off the roof of our six-story building. At the beginning, David convinced us to allow a friend of his who was a video artist to direct the show. But she had ideas about calling attention to the medium that resulted in a first tape (of Ted Berrigan reading) that for the most part was visually blank, with occasional glimpses of Ted. We decided that we wanted something less self-consciously theoretical and more sincerely documentary, and asked Rochelle Kraut to take over as director. I don’t think anyone would argue that the results made the technology transparent. Watching them, you’re conscious of every shift in camera angle and directorial decision.

Olin: Were you inspired by more overtly political uses of public access television? For example, Michael Shamberg’s notion of “Guerrilla Television” — public access as a means to bypass the cultural gatekeepers and “talk back” to corporate media.[6]

Lenhart: David and Greg might have had some ideas in this direction, but I was inspired by a series of readings I saw on public television while in college that was my introduction to John Wieners, Robert Duncan, Frank O’Hara, Robert Creeley, Charles Olson, and others. Before viewing them, the only poet I had ever heard read was John Ciardi. Those fifteen-minute televised readings changed my ideas of what poems could be.[7]

Olin: How did performing your poems in the TV studio compare to reading at more conventional venues such as St. Mark’s Church? Did the technical equipment alter the relation of poet to audience?

Lenhart: Because of the limits of studio space, the live audience was tiny. But there were poets behind the cameras, poets on the other side of the director’s glass, and usually a few poets crammed into the back of the room. Most of us were used to reading in much smaller venues than St. Mark’s, like the tiny bookshop on Sixth Street with a capacity of about ten people, so we were used to adjusting to constricted spaces. Those large, clunky, red-eyed cameras put some people off.[8]

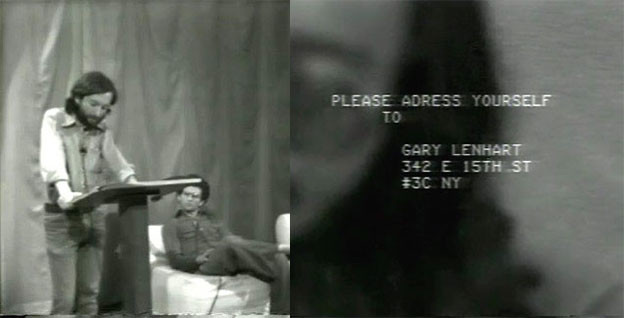

Olin: The host, Didi Susan Dubelyew, makes frequent requests for written feedback from viewers, giving your address on East Fifteenth Street. Judging by her remarks, it seems that nobody ever responded! Did you ever receive any feedback about the show from the outside audience?

Lenhart: No. It’s fairest to say that [the] audience was a rumor.

Olin: How important was it that people were tuning in? If nobody was watching the broadcasts, then what was the motivation?

Lenhart: Though we hoped that someone would tune in to the show, we left the studio each week with a tape that we hoped to show somewhere, sometime. And whoever read on the show knew that six or eight people had listened to their poems. As I mentioned, we were used to reading to audiences of that size.

Olin: Who typically attended the studio recordings? Was the show advertised anywhere, or was it just word of mouth?

Lenhart: As you might gather from the previous responses, the producers of Public Access Poetry were part of a tight community of mostly Lower East Side poets, though there were readers from other parts of town and even out of town (such as Joanne Kyger). Strictly through word of mouth, the audiences grew each week until the studio was often overcrowded and it became difficult to move the cameras.

Olin: Can you describe the technical set-up in the studio? What was your experience working with the equipment?

Lenhart: After the first show, or maybe two, when someone showed us how to operate the cameras, we arrived each week to a bare studio with two cameras and a microphone. We did everything ourselves. Danny Krakauer and Greg Masters most often served as camera operators, with David and Shelley Kraut in the director’s booth. Occasionally I would fill in for Danny or Greg, but mostly I just made sure we had the money we needed to pay the studio.

Olin: Some of the cable-TV shows produced by downtown artists at the time had corresponding viewing parties, in which the producers and their friends would get together in local bars that had cable TV and watch their broadcasts. Did anything of this sort occur with Public Access Poetry?

Lenhart: No. The first year, the show was broadcast live. And as I said, none of us had cable.

Olin: Did you ever watch back the recorded tapes as a group?

Lenhart: Not regularly, though I recall viewing some. It was a treat when we could.

Olin: During many episodes a significant amount of screen time is given to documenting the audience members listening to the readings. Was there a conscious attempt to depict the broader poetic community?

Lenhart: Fortunately, Rochelle Kraut was the director. She and Greg Masters are responsible for most of those shots. They both had a more refined sense of documentary than the rest of us.

Olin: Many shows feature quite formally experimental camera work — surreal superpositions and cross-fades, long shots of the poets’ hands and feet, long shots of the audience and such. Again, I’m wondering if this experimental style was a conscious decision, or was it more [of] a spontaneous thing?

Lenhart: It should be emphasized that the production was spontaneous, and I don’t recall many conversations about visual style, though Shelley might have discussed it with Greg or David. Greg and Danny were mainly responsible for the unconventional camera work. Greg’s motives were probably experimental; he was a huge Godard and Truffaut buff. Danny was also interested in experimentation, but some of his unconventional shots might have been inspired by pharmaceuticals.

Olin: At the time you were simultaneously working on Mag City, a mimeographed poetry magazine, which you edited with Greg Masters and Michael Scholnick. Were you trying to bolster a particular scene, or to promote a specific poetic style with Mag City, and did this carry over into Public Access Poetry?

Lenhart: Only Greg and I were producers of Public Access Poetry and Mag City. We were close friends, lived in the same building, attended many of the same poetry readings, art exhibitions, and movies, and listened to a lot of the same music. You could say the same of the third editor of the magazine, Michael Scholnick. I like to think that we were conscious; we certainly spent many hours every week talking about poems and other arts. But we didn’t agree about everything. When we didn’t, we would often print something that one of us felt strongly about, even if the other two disapproved. I don’t know how to characterize our aesthetic, except that it was less ironic than most of what was going on around us. At one time, Greg organized an art exhibition under the title The New Romanticism. We probably weren’t that new, but we were definitely Romantics. Of course, much of our taste carried over to Public Access Poetry, because poetry wasn’t David’s primary interest, and Danny was reticent and even passive. Shelley was invited to direct when we became dissatisfied with our first director. She became increasingly involved in programming, and her husband Bob Rosenthal became part of the crew, more on camera than behind. As Allen Ginsberg’s secretary, Bob often knew who was coming to town, and was important in suggesting and inviting readers.

Olin: The medium of television is typically not taken very seriously as a venue for high art or poetry. Do you see any correspondence between the quotidian, vernacular aspects of television and the broader poetics of the New York School?

Lenhart: I’ve been so close to the New York School for so long that I’m more aware of poetic individualities than similarities. But I don’t think many of the NY poets ever thought much about being “serious,” if by that you mean not daily or humorous, even funny. I’ve already mentioned stumbling upon poetry on PBS while I was still in school. Though I didn’t think it was very good, I also watched every episode of Voices and Visions in the ’80s, and enjoyed Bob Holman’s United States of Poetry. However you get it, whether on TV, in a bar or bookstore or church, or on the Internet, why not be grateful for the availability, even if most of it is crap? […] If you ever get a chance to see John Wieners reading from The Hotel Wentley Poems, don’t miss it. That’s the kind of magic I imagined when we taped Ted Berrigan, Alice Notley, Joanne Kyger, John Godfrey, Ron Padgett, Steve Levine, Eileen Myles, Ted Greenwald, etc.

Olin: Was independently publishing poetry mimeographs and producing your own cable-TV show regarded as a means to infiltrate the poetry establishment, or was it more important for you to build a local, noninstitutionalized form of poetic community?

Lenhart: For almost everyone involved with Public Access Poetry, poetry was just part of our lives and the basis for many of our friendships. Bob [Rosenthal] and Shelley [Kraut] were more involved in other kinds of neighborhood groups and organizing, so they might have a more coherent answer to this question. But I moved to New York City because I read books by Ted Berrigan and Ron Padgett in the University of Wisconsin library and wanted to be part of that — whatever that was. Once there, I was enchanted to make friends with people whose work delighted and challenged me. I didn’t think about infiltrating the poetry or, more broadly, art establishment. I just wanted to hang out with people whose company I enjoyed and to talk to them incessantly about poems, music, and art.

Olin: Was there much overlap between the East Village poets and the punk scene happening at CBGB or Mudd Club at that time? Did you take inspiration from the deskilled aesthetic and DIY ethos of punk?

Lenhart: I don’t know that Public Access Poetry did, though Greg played drums at CBGB as part of Tom Carey’s band, and Allen Ginsberg helped organize a benefit there with Andrei Voznesensky and Richard Hell (who was our neighbor). I mostly went to jazz joints, especially the Tin Palace and Village Vanguard, and to new music concerts, from Philip Glass and Steve Reich to [Karlheinz] Stockhausen and Elliott Carter. But I recall going with Steve Levine, who was much hipper than I, to see Talking Heads at a small bar on Third Avenue.

Olin: Did the group of poets involved with Public Access Poetry have a sense of yourselves as a younger generation, which was distinct from the more established “second-wave” New York School poets (e.g. Ted Berrigan, Alice Notley, Ron Padgett, Anne Waldman, Lewis Warsh, Bernadette Mayer)? If so, could you comment on any major differences — stylistic, social, or otherwise?

Lenhart: Though most of the Public Access Poetry group was younger, Danny must have been around sixty, which made him older than all the poets you mention. Though I didn’t arrive in NYC until I was twenty-four, I was only several years younger than most of the others you name. None of the PAP crew, however, had known Frank O’Hara or Jack Kerouac or Paul Blackburn, which sounds coincidental, but I think crucial in some way to our sense of ourselves, our community. That is, the Beats and the New York School were already history. And none of us were famous or, so far as I know, ever aspired to be so. (Though if you’re including Dodgems, that may have changed when Eileen Myles decided to run for President.) As Alice Notley wrote, we did have a sense that we were “coming after” not just the New York School and the Beats, but after the Civil Rights movement and the ’60s, too.[9]

Olin: The collaborative and independent production of a public access show seems comparable to putting together a poetry magazine. Would you situate Public Access Poetry as part of a broader tradition of self-published poetry magazines/mimeographs in the East Village?

Lenhart: Yes, that’s where I would put it, if by self-published you distinguish between the current industry of paid publication and publishing as a communal endeavor, that is, to publish your friends because you want to read them. As George Schneeman said about Mag City, it was the perfect size to read on a long subway ride — and you didn’t have to feel guilty about throwing it away when you arrived at your destination.

Olin: Poetry mimeographs generally have a much shorter lifespan than books, and typically shun the glossy high-quality finish of professional magazines. To some degree, the same could be said of Public Access Poetry. Do you think that these ephemeral qualities reflect a specific politics or poetics?

Lenhart: This is a complex issue. Glossy high-quality finish implies expense. We tried to do the best job we could without spending money that we didn’t have. When Mag City received a grant, we didn’t spend the money on a party but immediately tried to upgrade the quality of production. When we could afford it, we used color video instead of black and white. We weren’t being sentimental or nostalgic. We were working within the financial constraints of people with forty-hour jobs at substandard pay. Danny, who worked in the post office, and I, who worked as a recording engineer for the Foundation for the Blind, probably had the most money.

Olin: Was the relational fabric of the East Village an important catalyst to the poetry scene depicted on Public Access Poetry? How important was mutual geographic proximity?

Lenhart: Every one of the main producers of Public Access Poetry (Greg, Danny, David, Bob and Shelley, myself) lived between Seventh and Twelfth Streets, east of First Avenue. To see each other only once a week was rare. We were neighbors as well as collaborators. That seems important for understanding the casual nature of the productions and gatherings. You didn’t need a newspaper to advertise an event — or a TV show. News moved by word of mouth.[10]

Olin: It’s interesting that television (literally “vision at a distance”) is generally thought of as a medium with which to bridge distance and create a sense of proximity, and yet here you have a very localized and close-knit collection of poets who chose to broadcast themselves. Did you have any specific (wider) audience in mind that you wanted to reach?

Lenhart: I’m not sure that we understood the implications of distance. We were close to each other and to others from Chicago, Iowa City, or San Francisco who were involved in similar explorations. It would have been nice to show those tapes in any of those places. And then maybe we all had the dream of that kid alone somewhere, as I had been when I first saw poetry on TV, and hoped to reach her.

Olin: I was wondering if you had any thoughts about Public Access Poetry recently becoming available online? Now people can effectively tune in at any given time and from any location. Obviously this is wonderful in terms of facilitating access to the archive, but it also means that the temporal synchronicity of a live broadcast gets lost. Do you regard this as a drawback?

Lenhart: Despite the communal nature of its production, and perhaps contrary to the evidence of many of my responses, I don’t think temporal synchronicity is vital. I saw the showings at Anthology Film Archives last spring, and though the audience consisted largely of people who were not even alive when the tapes were made, I had the impression that viewers could appreciate and distinguish performative and poetic values. Or maybe that’s my own sense of the poem being transmitted person to person.

Olin: PAP had a relatively short run. How and why did the show end?

Lenhart: I can’t remember how things fell apart. It took commitment from all six of us to keep it afloat for as long as we did. Maybe we tired of each other or of squabbling about whom to schedule. Maybe some wanted to use their money to pay the rent. About the time of Public Access Poetry’s demise, I started spending more time with the woman who would become my wife. Shelley and Bob’s first child, Aliyah, was born. Maybe Greg or I changed jobs, which we did often and not always for more money. It wasn’t like we could hire someone else to take our place. But I don’t think we wanted to continue either.

1. This group of writers came after the better-known “first generation” New York School poets, such as Frank O’Hara, John Ashbery, Kenneth Koch, and Barbara Guest. On “second generation” New York School poetry, see Daniel Kane, ed., Don’t Ever Get Famous: Essays on New York Writing after the New York School (Normal, IL: Dalkey Archive Press, 2007); Maggie Nelson, Women, The New York School, and Other True Abstractions (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2007); Steven Clay and Rodney Phillips, eds., A Secret Location on the Lower East Side: Adventures in Writing, 1960–1980 (New York: Granary Books, 1998); and Brandon Stosuy, ed., Up is Up, But So Is Down: New York’s Downtown Literary Scene 1974–1992 (New York: New York University Press, 2006).

2. Greg Masters, telephone conversation with the author, January 4, 2012. Masters discusses Public Access Poetry in a 2011 interview on WKCR-FM.

3. Mag City was launched in 1977 by Gary Lenhart, Greg Masters, and Michael Scholnik, and featured many of the same poets who appeared on the show. Masters provides the following summary: “Mag City was a party in print. It was started to give form to a literary scene that existed in the East Village. The work [...] is decidedly unacademic, meaning the poems’ emphasis is content, not form, leaving rough edges, all the more for impact. [...] The poems were often chatty and attempted to be accessible and entertaining by discoursing in common speech. They celebrated the common, the daily, the immediate.” Greg Masters, qtd. in Steven Clay and Rodney Phillips, eds., A Secret Location on the Lower East Side: Adventures in Writing, 1960–1980 (New York: Granary Books, 1998), 233.

4. This sense of broadcasting to a speculative, future audience was shared by many of the poets involved with the show. As Bob Rosenthal recalled, “... it was like sending time capsules into space.” (Bob Rosenthal, telephone conversation with the author, December 18, 2011). For Eileen Myles, “The communication was with the future, in the most radical way — there was a whole tradition of New York poets slightly older than us writing poems that were addressed to ‘Poets of the Future!’ It was kind of a joke, but then I think everybody meant it, too. And then we also felt that we were the poets of the future.” (Eileen Myles, telephone conversation with the author, January 18, 2013).

5. ETC studio was located at 110 East Twenty-Third Street. The studio was opened in September 1974 by Jim Chladek, a public access enthusiast, who persuaded Time Warner — whose offices were located next door — to throw a live TV cable over their roof and in through his fire escape. On ETC studio, see Jim Chladek and Michael McClard, “The Writing on the Wall,” in BOMB 3, 1982: 16–18.

6. See, for example, Michael Shamberg, Guerilla Television (New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1971); Deirdre Boyle, Subject to Change: Guerrilla Television Revisited (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997).

7. These poetry films were produced by Richard O. Moore, a poet and documentary filmmaker. (Gary Lenhart, email message to the author, August 19, 2016).

8. Ron Padgett, for example, recalled how, “I remember being very aware of the fact that there was a camera there. You had to kind of read into the abyss, but at least there were bodies out there in the darkness, and they would chuckle occasionally.” (Ron Padgett, telephone conversation with the author, December 11, 2011.)

9. See Alice Notley, Coming After: Essays on Poetry (University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, 2005). On Eileen Myles’s poetry magazine Dodgems (1977–79), see Clay and Phillips (1998): 222–23.

10. At the time, many of the poets involved with Public Access Poetry lived in the same building on East Twelfth Street. As Greg Masters recalled: “We were mostly living up on Twelfth Street. Someone referred to that building once as the ‘Boys’ Dorm’ and that name kind of stuck. Bob Rosenthal and Shelley [Kraut] were the first to move in, and then Allen Ginsberg moved in, and that attracted the rest of us. Gary [Lenhart] and Michael [Scholnick] moved in, and then I moved in, and then John Godfrey, Larry Fagin, Jim Brodey. Many musicians lived there, too. Richard Hell lived there — still does, right next to me. It was a fun building. Our rent was very cheap — we had no heat or hot water, but that mattered less to us than being in the East Village.” (Greg Masters, telephone conversation with the author, January 4, 2012.)