'Walking out the right door'

A review of Richard Blevins's 'The Art of the Serial Poem'

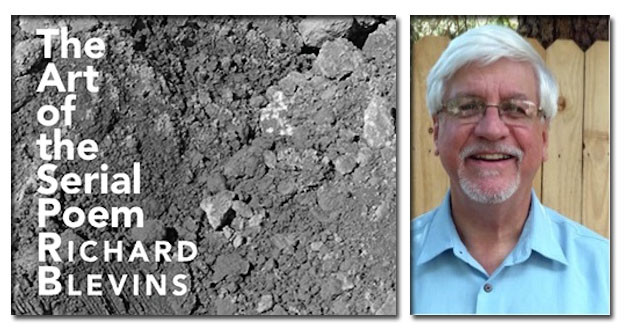

The Art of the Serial Poem

The Art of the Serial Poem

And, words, word, words

all over everything.

— Charles Olson[1]

What exactly are the demands of my art?

— Richard Blevins[2]

For nearly forty years, the poet Richard Blevins has been a fortuitous and immensely productive figure in contemporary American poetry. Blevins’s project is one securely grounded in the work of his modernist forebears: Ezra Pound, William Carlos Williams, and Charles Olson (whose compass is never far from Blevins’s map of “Amerika”). At the same time, Blevins’s project in serial poetics follows that path up through such later figures as Robert Duncan, Ken Irby, Gregory Corso, and Gerrit Lansing. Both a distinctly elegiac response to predecessors and a significant contribution to avant-garde conceptions of serial form, Blevins’s compendious The Art of the Serial Poem delineates a landscape of “ghost poets” whose company Blevins both shares and laments. At its best, this collection, one that represents this poet’s lifework, draws powerful energies from Blevins’s predecessor and companionate figures in art, literature, and music, while at the same time offering a reading of late modernism and the art that emerged in its wake.

In “d.a. levy Would Disagree: Statement for the Lakewood Session, April 10, 2012,” Blevins writes:

I write long poems because, in my experience, it is only during the act of composition, and then only sometimes, that the horrifying facts of so much history and so little life make a disorderly sense. By sense I mean that altered state, a temporary paranoia that can last over days, when everything I read or overhear fits into my composition, my text providing a context flowing into and out of my life.[3]

These lines that later appear in lineated form in Blevins’s serial composition, Rothko’s Door to Duncan’s Field (& The Trauma of Smithson’s Mudslide), serve as an apt introduction to this epic volume of work produced over a forty-year span. This is an important book for followers of descendants of the New American Poetry tree, and represents a life work that spans Blevins’s career-long effort to abide a writing practice of “a context overflowing into and out of my life.” Both visionary recital of “angelic orders” and fierce eclogue of lived experience, The Art of the Serial Poem tracks Blevins’s effort to bring the daily, reported factuality of life into conversation with this volume’s assiduous hybridity, its movement from lineated poetry to essayistic prose and back again.

The Art of the Serial Poem covers a lot of ground, providing both a context and defense for work that includes as part of its diverse company a mix of writers and artists — Robert Duncan, Roberto Bolaño, Ed Dorn, Joel Oppenheimer, Robert Smithson, d.a. levy, and Robin Blaser among them. Arranged by individual book project, The Art of the Serial Poem collects in one volume all of Blevins’s productive output through 2014, starting with Castle Tubin (2006) and ending with Rothko’s Door to Duncan’s Field (2014). Along the way, Blevins includes extended poem-works on the photographer Fred Day (Captivity Narratives,2008), Jim Morrison (The Morrison Poem,1992), and the crime novelist Raymond Chandler (The Collected Later Poems of Philip Marlowe, 1998).

Part writer’s notebook, part formalist experiment in the long poem, part scrapbook, and part extended meditation on avant-garde practice in the wake of modernism, Blevins’s work in The Art of the Serial Poem refuses any singular style in favor of an eclectic mix of open form, field composition, and traditional forms for work that moves at a fast clip in its exhaustive movement through different periods, formal concerns, and disciplinary areas. A casebook in serial form, Blevins’s account is one of the more generous and varied we have, both bildung and record of an inquiry into “the experience of America … to look / up from Donne, into MISSOURI, MISSOURI” (201). A student of Ed Dorn’s at Kent State University while an undergraduate, and editor of the last two volumes of the Olson/Creeley correspondence following the death of George Butterick, Blevins dates his beginnings as a serious poet to his participation in a seminar Robert Duncan gave at Kent State in the fall of 1971. As Blevins writes to Lisa Jarnot in 1997, “I was one of Robert Duncan’s students in his seminar on The Imagination … I date my birth as a poet from that time and place.”[4] Duncan’s presence in The Art of the Serial Poem gets registered most notably in the documents and photographs that appear throughout this volume, including a photocopy of Duncan’s syllabus for his Kent State seminar (145), undated photographs of Duncan and Blevins standing outside of Duncan’s San Francisco home (662–63), and a typescript of an essay by Duncan first published in Io, “Reading Rich Blevins’ essay ‘The Moment of Vision’ and, Thinking of Pound’s Cantos” (671).

Blevins’s recognition of Duncan’s important place in his own evolving life poem is forcefully restated in the book’s closing poem, which serves as both a coda to the many books collected here and a précis on contemporary poetics via the Berkeley Renaissance and Black Mountain:

The Pisan Cantos Paterson Jubilate Agno Jerusalem II

and IV required texts on Studies on Ideas

of the Poetic Imagination syllabus Robert Duncan sent

from San Francisco to Kent State First thing

I do that impresses my instructor is immediately

see his assignment (“Make a constellation of poets

who influence you” done with Spicer and Helen

in the famous magic workshop) makes a door

shape A version was published in Io following

Duncan’s introduction “Reading Rich Blevins’ ‘The Moment of

Vision’ And Thinking About Pound’s Cantos’ so I’d

opened the door and couldn’t write a line

for two years defenestrated […] (672)

Blevins’s wry humor and wit come into full view here, as does the career-making meeting that, arguably, sets Blevins on his course. That’s not an understatement in a collection that has serious business to do with these instigator male presences (Olson, Duncan, Butterick, to name just a few). Blevins’s project is, in part, a statement on his participation in helping forge linkages between his own evolving understanding of himself as an American poet within a tradition of avant-garde expression that extends from tutelary moments such as this.

While Duncan’s Passages series bears little resemblance to Blevins’s serial constructions, the animation of form that Duncan sets forth finds its way into much of what’s here. That’s not to say that women writers are not important to this project (notably Helen Adam, Emily Dickinson, HD, and Sharon Doubiago, who appear as talismanic figures of poetic process and creation), but it is to recognize that, for Blevins, the site of initial self-authorization as a writer goes back to initial encounters with male influence and models. Duncan’s early impact gets restaged in the long poem that serves as culmination and apogee of poetic statement for the work that’s led us here:

[…] Floor’d Duncan say one

day, “Draw a self-portrait” So I went home

and drew a dollar as accurately as I

could but instead of George Washington’s it was

my face He fancied it immediately swapped me

for his self-portrait, “A Drawing of Someone Else

Appearing in Avoiding My face in the Mirror”

fading ink on laundry cardboard frame on my

walls in every apartment and house these years (672)

Interestingly, this poem also brings in another important member of Duncan’s community, John Taggart, whose “Rothko Chapel Poem” Blevins would here seem to be alluding to. Insofar as Blevins’s project charts a particular moment in postwar American poetry dominated by white male figures, it’s worth noting that his reading of US history in Taz Alago (1983), dedicated to the screenwriter and novelist Will Henry, complicates the formations of whiteness — if not maleness — that otherwise dominate Blevins’s account. In poems that meditate on the position of “white history / white noise” (177) and Montana’s contemporary status as “vacation buffalo grounds” (176) for white tourists, Blevins laments the cultural position of “warriors without buffalo” (176). While Blevins doesn’t significantly revise our historical understanding of the systemic genocide of Native Americans in the West, his work in Taz Alago gestures toward an awareness of the complicity between constructs of whiteness and the reinscriptions of cultural supremacy and political violence that Blevins recognizes as inseparable from “white history.”

While The Art of the Serial Poem travels in part under the sign of Duncan, it does so by means of its own individualized and relentless investigation of seriality as practice over time, of “duration” as a singular feature of poetic production. The poems attest to Blevins’s conscious effort to craft a poetry that is porous in its stance to the world outside the poem. As Blevins frames matters in a recent interview with Tod Thilleman: “The writer of a serial poem is actually engaged daily for long periods of time. Over the duration of my work on a serial poem, when I compose I am aware that my mind dwells upon the emerging section even as I am permitted to dwell — live again — in the ongoing poem.”[5] Unlike Duncan’s conception of the serial poem as a response to and furtherance of cosmological and mythopoetic certainties or Creeley’s formal conception of seriality as one in which poems develop through an understanding of “one thing / done, the / rest follows,”[6] Blevins’s poems seek to talk their way through textuality in poetry that is not so much a container of thought as recognition of a state of becoming vis-à-vis language. The project can never be completed, a recognition that The Art of the Serial Poem puts forward repeatedly; the work can as a result have an obsessive feel to it, as the need to dwell within the poem’s compositional serial time takes precedence over other forms of experience.

This Heideggerian articulation of the poem’s driving force as a practice of “in-dwelling” leads to much of The Art of the Serial Poem’s most distinctive and rewarding riffs, as in the following lines from “Night Paving,” included in Castle Tubin:

finally we arrive

at a place only

because our travel

toward it must

eliminate arriving

at any other place

That is, we drive in a tradition of arrivals.

For the river must ever forget its source.

For the river will change its course.

Drove all day back across Pennsylvania,

day unto night in Enterprise’s car, knowing

the nail was There in their Tire,

too tired to figure our chances.

The philosopher and the poet

shared the driving, therein

happy a man

cannot know

the day of his exit. (68)

Later, in “Preludes and Fugues,” also from Castle Tubin, Blevins incorporates prose and musical notation to create a layered autopoetic biography:

“D Flat major, no 42”

Wolf Kahn calendar

For February

An old barn sags

Inward, upon itself

The tree beside it

Branches up and out.

Arms would not hands

Could not reach him.

I had always wanted to be an artist, thot of myself as an artist, looked at the world with an adolescent’s artist-in-training eye. I turned out on request charcoal portraits of friends of the family, drawn from photographs. Norman Rockwell wrote back to my 5th grade teacher, “Thank you for the drawings by your student … If Richard applies himself and works hard …” By 16, I realized my limits … When I first read poetry, about then, I mean the poems they did not mention in school or seem to have read — some pages of Pound, then the Donald Allen anthology that starts with Olson and Duncan — I hoped I could learn to work in language. (102)

Beginning with a reference to Shostakovich’s “Preludes and Fugues,” Blevins moves to a brief depiction of a scene from a calendar featuring the paintings of the twentieth-century German-born American painter, Wolf Kahn. Isolating a figure whose “Arms would not hands / Could not reach him,” Blevins works his way from this closely observed, compacted scene to a meditation on his own connection to the visual arts that gave way to a lifelong absorption in poetry. Like so much of The Art of the Serial Poem, the ambition documented here is to forge poetry capacious and thought-full enough to move quickly, adeptly from musical composition to painting to poetry, and to do so in a way that forms a tissue of references and theoretical propositions, the interconnections among which Blevins wants his readers to understand are fundamental to the experience of seriality both as composition and, to cite Olson, a “stance toward reality.”[7]

As in the case of Roland Barthes’s ideal reader seeking and giving pleasure to the ongoing flow of language, a state without clear beginning or end,[8] Blevins moves us to consider the position of reader/writer in language that is always already anticipating the poem’s appearance:

Bunting chose prison. Rilke went to war too quickly. Celine. No one escaped it.

This is not a poem you can keep in your head all day, taking notes, taking time. I find I can start it up again for two-hour writing session by reading Celan. Other times, Neruda instead. When I save the poems to file, this is what the program makes the title. “Not a painting to hang on someone.” From the couplet at the start of the first draft pages that read: “Not a painting to hang on someone’s wall finally / But the public act of painting on wall and ceiling.” (126)

Indeed, Blevins’s writerly reader occupies a space of associative jouissance and readerly pleasure, as he both claims a space of poetic making for himself and those he would become and shares this process with extraordinary openness with whoever is willing to take the journey with him. As Blevins writes in a segment from Fogbow Bridge: Selected Poems (2000):

(The taxi’s headlights

at night idling

in the (idle) trees

winter stands by

the falser folds

of our youth:

madness free

love

intoxication

This is the triumph

of life, this is

the unfinished page

newly

disc

-overed in the

drowned sun’s

pockets

at the bottom

of the sea

(304)

Coming two pages after reproduced handwritten notes related to “things I’ve done on mescaline” (300), these lines move imagistically down the right-side margin, demarcating that realm given over to “the unfinished page” of poetic making. Like Paul Blackburn, who, as Robert Kelly put it, “sought and found in the happenstance of experience a mysterious beauty called music,”[9] Blevins deploys the notational and quickly observed detail here and throughout the serial works that fill out The Art of the Serial Poem to articulate a lifelong poem of omnivorous intellect and inner need.

“I write to kill time […] I write to be alone for part of each day” (209), Blevins writes in Three Sleeps: A Historomance (1992). It’s a serious wager placed against unknowable odds, as the poet brings in everyone and anything he can remember, everything he can write down on napkins, stray pieces of paper, index cards, to connect himself to a world indebted to Melville and Dickinson, Crane and Rimbaud, Joel Oppenheimer and Gerrit Lansing, among many others. “It is never a question of finding forms / big enuf to include everything It is ever / a matter of walking out the right door” (676). Or, as Blevins puts it elsewhere in The Art of the Serial Poem:

I come to poetry

Precisely because.

[It] has taught me

To live with the feeling

You’ve left something essential behind. (206)

In ways similar to Robin Blaser’s The Holy Forest, Blevins’s The Art of the Serial Poem intentionally explores both the limits and possibilities of seriality, while at the same time using his poems to document the art and artists who influenced his own life and art-making. It is a poetry as much about the preservation of cultural memory as about artistic ambition; as much about poetic language as a bridge between world and self as about the potentiality of human consciousness to bear witness to a world that is at each instant appearing and disappearing. The “something essential left behind” serves, then, as both recognition of Blevins’s ongoing belief in “the inspired Word / on every page” (597) and his certitude in the necessity of providing a record in poetry equal to the life.

1. Charles Olson, The Maximus Poems (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983), 17.

2. Richard Blevins, The Art of the Serial Poem (New York City: Spuyten Duyvil Press, 2017), 686.

3. Richard Blevins, “d.a. levy Would Disagree: Statement for the Lakewood Session, April 10, 2012,” manuscript copy emailed to author, June 14, 2017.

4. Lisa Jarnot, Robert Duncan: The Ambassador from Venus (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012), 511.

5. Richard Blevins, “The Tradition of Arrivals: The Serial Poem in Context,” interview with Tod Thilleman (unpublished manuscript), 1.

6. Robert Creeley, The Collected Poems of Robert Creeley (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982), 388.

7. Charles Olson, “Projective Verse,” in Collected Prose, ed. Donald Allen and Benjamin Friedlander (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 239.

8. See Roland Barthes, The Pleasure of the Text, trans. Richard Miller (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1975).

9. Robert Kelly, introduction to The Journals by Paul Blackburn, ed. Robert Kelly (Los Angeles: Black Sparrow Press, 1975).