A provisional map of who/what/where we are

A review of 'Inciting Poetics: Thinking and Writing Poetry'

Inciting Poetics: Thinking and Writing Poetry

Inciting Poetics: Thinking and Writing Poetry

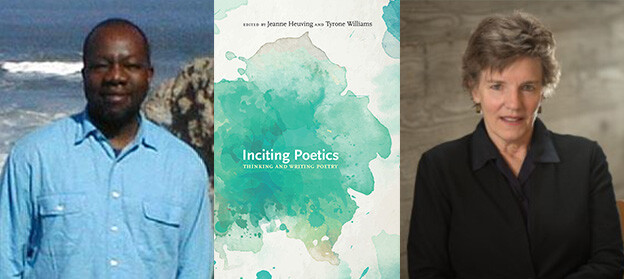

When I first learned that the University of New Mexico Press was publishing Inciting Poetics, a collection of essays edited by Jeanne Heuving and Tyrone Williams, I was excited for a number of reasons. A big fan of both Heuving’s and Williams’s work in poetry and criticism and of the Recencies series University of New Mexico has been publishing over the last several years (notable volumes include the republication of Robert Creeley’s Presences: A Text for Marisol; Robert Bertholf and Dale Smith’s coedited collection, An Open Map: The Correspondence of Robert Duncan and Charles Olson; and Dennis Tedlock’s The Olson Codex: Projective Verse and the Problem of Mayan Glyphs), I was intrigued to learn what the writers collected in Inciting Poetics had to tell us about different angles on the subject of, as the book’s subtitle has it, “thinking and writing poetry.” With its critique of the current moment in poetry and poetics and its call to rethink how we do what we do as writers and thinkers of poetry, Inciting Poetics organizes itself around one powerful question: What are poetics now? These essays, which originated as talks delivered at the 2012 Convergence on Poetics that inaugurated the MFA in Creative Writing and Poetics at the University of Washington Bothell, go forward to explore different responses to this question through four discrete sections, “Part 1. What Is Poetics?”; “Part 2. Critical Interventions”; “Part 3. Cross-Cultural Imperatives”; and “Part 4. Digital, Capital, and Institutional Frames.” The fourteen essays that tell this story of contemporary poetics are, to be sure, a provisional map of who/what/where we are. For readers new to the conversation, they’re an informative, if, arguably, incomplete, view of the landscape. For others (readers of Jacket2, e.g.) who’ve been keeping up with the “new” in contemporary poetry and poetics in the US over the last several decades, the essays individually work out useful, if not always groundbreaking, responses to the volume’s central concerns. Collectively these essays frame out for us important strands of an ongoing inquiry into the ethical and political values at stake in poetry today from a group of poet/critics and scholars whose own impact on poetry and poetics continues to be decisive.

On one level at least, Inciting Poetics would seem to be in dialogue with Donald Allen’s 1960 iconoclastic anthology of poetry and poetics, The New American Poetry. With the majority of this volume’s contributors having come of age in the 1960s and 1970s and now in their sixties and seventies, the essays collected here tell a particular narrative, one that seems acutely linked to the political upheavals and cultural shifts of those formative decades. While a key difference between The American Poetry and Inciting Poetics remains the former’s focus on poetry with a supplemental end section featuring statements on poetics (a companion volume, The Poetics of the New American Poetry, would be published in 1973), Inciting Poetics nonethelessreverberates with and even echoes some of the consequential debates about poetries’ necessities, adequacies, audiences, and purposes that have been part of the cultural conversation in the US at least since the 1950s.[1]

In an orienting move that has consequences for how we’re meant to read this collection, Heuving and Williams represent this collection as building on the important work accomplished in the previous century’s magazines and journals, such as Bruce Andrews’s and Charles Bernstein’s L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E (1978–1982), Kathleen Fraser’s How(ever) (1983–1991), and Nathaniel Mackey’s Hambone (1974–present), and monographs and essay collections such as Charles Bernstein’s Content’s Dream (1986), Aldon Nielsen’s Black Chant: Languages of African American Postmodernism (1997), and Kathleen Fraser’s Translating the Unspeakable: Poetry and the Innovative Necessity (2000), all of which set the stage for the “turn to language” that Heuving and Williams argue has become absorbed into the bloodstream of contemporary poetry and poetics. While these publications serve as the contextual bridgework for the project undertaken by Inciting Poetics, the editors importantly also separate their work here from Cole Swenson and David St. John’s coedited American Hybrid: A Norton Anthology of New Poetry (2009). In so doing, Heuving and Williams draw attention to what they suggest is that anthology’s false proposition that “the experimental and the traditional … have now found a happy medium.”[2] It’s their contention here that nothing could be further from the truth; they argue that “our epoch differs from the preceding century in that the turn to language has so permeated the understanding and practice of poetry and poetics as well as other fields of endeavor that it no longer serves as an urgent impetus or an organizing question.”[3]

This binary is in certain respects a false one, since the project that Swenson and St. John put together in American Hybrid is at a distant remove from the aims and collective sensibility of Inciting Poetics. More importantly, though, Inciting Poetics celebrates and reinvigorates the materialist and sociopolitical agendas of poetry promulgated by the Language writers of the 1970s and ’80s through talks, essays, and statements that originally appeared in the L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E newsletters and other pubs of the era. In so doing this collection accepts as axiomatic that Language writing’s various critiques of the connections between social realities and poetry’s “turn to language” no longer need to be redrawn since such critiques have become an organizing aspect of poetic production in the US since the 1970s. What’s important for this collection is that it travels with this kit in its travel bag, so to speak, and lays out a trajectory that proceeds from the premise that the attention Inciting Poetics pays to the validity of poetics wouldn’t have been possible without the interventions of Language writings and their particular critiques of poetic form and value.[4]

Without belaboring the point, in casting the Norton anthology up against their own work in Inciting Poetics (and it should be pointed out that the former collection seeks a decidedly heterodox mix of mainstream and experimental writing), Heuving and Williams situate their own work here in conversation with and among a set of poets who travel in a cultural and literary landscape of opposition and resistance to any single dominant narrative of literary production and value. That is to say, the orienting argument of Inciting Poetics vis-à-vis Language writing and its ongoing relevance to the questions this collection takes up doesn’t necessarily hold true for all, or even the majority, of the contributors included here. But this volume’s push to situate its critique in a present of “radical social and cultural change with respect to identity movements and their evolution [that] continue as well as an accelerated technological and media revolution”[5] remains a notable and important one. And it leads to a recasting of responses to questions that are central to this volume’s revisionist agenda: “What is a poet? What is poetry? What is poetics? What does poetry do? What might it accomplish?”[6]

To answer these questions, Inciting Poetics invokes a genealogy that surprises to the extent that it remains fairly focused on poets who were writing or had their greatest impact in the mid-to-late twentieth century. That’s to say, this collection wants its readers situated firmly in the present era of poetic production, while the writers under study in the essays gathered here tell another story. An abbreviated listing would include, moving in order of their appearance in the book: Robin Blaser, Louis Zukofsky, George Oppen, Charles Olson, Rosemarie Waldrop, Frank O’Hara, John Ashbery, Ezra Pound, Robert Duncan, Nathaniel Mackey, Jennifer Bartlett, Mark Nowak, Denise Levertov, Gwendolyn Brooks, William Carlos Williams, Cathy Park Hong, Garry Thomas Morse, Guillermo Gómez-Peña, Stanley Kunitz, Wallace Stevens, Gershom Scholem, Taha Muhammed Ali, Mahmoud Darwish, Jorie Graham, Kenneth Goldsmith, and Craig Dworkin. While such a listing isn’t conclusive in its representation of the work that gets done here in the individual essays, it does provide a glimpse of this collection’s heavily retrospective cast and the ways in which Inciting Poetics remains firmly anchored in writers from the last century. In short, this book’s call to revisit earlier practitioners for a new understanding of where we are now vis-à-vis poetics is an admirable one, at the same time that this goal isn’t entirely realized in the context of the subjects under study in this collection.

Even as Inciting Poetics seeks to redefine different portions of the cultural territory transected by each of its sectional divisions, it fails to do such in one key way: an absence in this collection of work directly responsive to Black innovative poetries and poetics. With the exception of Nathaniel Mackey’s excerpted contribution from Late Arcade, a volume in his ongoing epistolary fiction, From a Broken Bottle Traces of Perfume Still Emanate, Inciting Poetics turns away from innovative poetry and poetics by Black writers such as Harryette Mullen, Fred Moten, Ed Roberson, Dawn Lundy Martin, and M. NourbeSe Philip and seeks instead to show the dynamics of “multiple cultures, races and ethnicities in relation to each other.”[7] In so doing, Heuving and Williams argue that the writers considered in the section titled “Cross Cultural Imperatives” “draw attention to difficulties inherent in liberal solutions of diversity and tolerance, given the indelibleness and complexity of culture itself, especially within already racialized and racist societies.”[8] The value of this approach potentially lies in its alertness to the different presentations of cultural power and the ways in which white privilege can mask efforts at sublimation and co-optation. However, I’m mindful of C. S. Giscombe’s pointed question from Aldon Nielsen’s introduction to What I Say: Innovative Poetry by Black Writers in America, “What does race do in anthologies?”[9] Race, like other identity categories, can find its way into an anthology on primarily inclusivity-for-inclusivity’s sake, which is partly Nielsen’s point. In the case of Inciting Poetics, however, the problem isn’t about inclusivity, per se, but about a gap in coverage of necessary voicings that would deliver on the collection’s promissory claim to be answering “What is poetics now?” The important contributions of Black innovative writing, particularly in the area of poetics, are not taken up here in the section where they arguably could and should be or in the collection as a whole. That’s a curious lacuna in a volume that incorporates otherwise pertinent and diverse critiques to establish greater clarity on the role of poetics in contemporary poetic practice and cultural thought.

*

The book’s opening section includes three very different responses to the question “What is poetics?” from Lyn Hejinian, Rachel Blau DuPlessis, and Nathaniel Mackey, poets in different stages of late career whose work continues to play a vital role in the shaping of conversations staged by this collection. Their responses to this question mark both a generational stance and each poet’s cumulative understanding of the continuing relevance of considerations of poetics to their practices and ongoing productivity. Hejinian comes at the question through the lens of social constructivism, and addresses the connections between a thirteenth-century Icelandic poem by Snorri Edda and contemporary formations of poetics and the social, a move that allows Hejinian to forward her own engagement in poetics as a space of socially legible practice “without ambiguity.”[10] Following from Hejinian’s emphasis on the political as inherently part of the social practice of poetry, Rachel Blau DuPlessis forwards a conception of poetics that is saturated in the polyvocal and ludic qualities of poetic making, the situatedness of writing as both material practice and an erotic play of pleasure, intellection, and ethical inquiry. DuPlessis usefully points out the slippage that occurs between poetry and poetics, the ways in which each can exist in tension with the other in the course of any one poem or essay: “It is necessary to query whether the essay in your hands now is ‘about’ or ‘on’ poetics in general, or whether it is ‘of’ or ‘inside’ a specific poetics.”[11] Mackey’s contribution takes a more allusive approach to the problem, situating poetics in the realm of community formation and the “legibility” of any artistic production. In the case of Mackey’s fictive jazz band whose performance results in a form of “illegibility” and proposes a kind of segmenting of audience, performance, and response, the legibility of the performance (its poetics) gestures toward the boundaries of outsider/insider.

While the social exists for each of these essays as connecting tissue, the approaches taken in this first section also document resistance and nonuniformity of approach. The stakes of the work involved, as DuPlessis reminds us, in this conversation, this weaving into and out of different states of praxis and meditative concern, are high, and form themselves around a singular and deeply modulated understanding of poetic practice: “One wants a truth but not the law.”[12] It’s a précis that fuses together disparate strands of this book’s approach to poetics and the multiple agendas that drive Inciting Poetics forward.

Having staged the anthology’s central question, Part 2, “Critical Interventions,” proposes a series of strategic rereadings and rethinkings of the present-day, based on work gathered from the prior century. There’s a salient logic to this, as Charles Altieri focuses his attentions on the work of Frank O’Hara and John Ashbery, at the same time that he qualifies the attention to language as the site of operations and calls for attending more rigorously to poems as “purposive actions” that allow us to move beyond considerations of language-qua-language to the “rhetorical domain” that provides us an important window into “the ways that language performs the task of helping audiences see in to the imaginative states the works make present.”[13] In so doing, Altieri seeks to bridge two important critical interventions by the poet Charles Bernstein in his A Poetics (1992)and Content’s Dream (1986). The compensatory gesture toward O’Hara and Ashbery and action painting of the 1950s is then linked to more recent work by Joshua Clover, a move that allows Altieri to pitch his aim all the higher in the recognition that “poets must make visible their love of something.”[14] Heuving and Elisabeth A. Frost create still other interventionist strategies for answering where we are or need to be now. For Heuving, resolution of the form/content split comes from recognizing the mediumistic qualities of language or the ways in which language is always moving through the poet. Her argument, then, moves away from solely materialist aspects of language (a nuanced shift notable for its qualifying of Language writing’s theorizing of the centrality of language as such) and allows her to incorporate the “diverse entities formed by language, namely myths, genres, tropes, thoughts.”[15] Frost isn’t far from this line of thinking, as she proposes a contextualization of poetic form vis-à-vis its methods and means of approach, the subjectivities incorporated into the work, and the latent transformational record the work produces among communities of readers. The move is a reflexive one that calls for renewed attention to the lyric “I” that, Frost reminds us, “still holds transformative potential and political efficacy.”[16]

Cynthia Hogue’s essay on the Robert Duncan/Denise Levertov rift over their different and deeply opposed responses to the Vietnam War, “To Make from Outrage Islands of Compassion,” concludes Part 2. Offering here a new reading of this important moment in 1960s American poetry, Hogue provides a sympathetic lens through which to view Levertov’s effort to “create an alternative subjectivity, which could bridge the divide between the eyewitness and the one bearing witness.”[17] The focus on “compassion” as a controlling vector of poetic making is notable here, in that Hogue would have us understand how, beyond the imaged anger that Levertov recounts in poems such as “Staying Alive,” from which the title of this essay is quoted, the poem forms a bridge to the real that is dependent on “the act of not looking away, of eye-witnessing.”[18] In Hogue’s reading of it, the dissolution of subjectivities that Levertov instantiated in the poem’s own refusal to look away forces up a critical awareness of both the limitation of representation and the urgent need for ethical positioning of the witnessing/experiencing subject.

The three essays that form Part 3 push at questions of race and ethnicity under the title of “Cross-Cultural Imperatives.” In so doing, the three contributors to this section cast a wide net that includes ethnographic writing and its relation to the discourses of “observation, performance, power, and consent” that have spurred on much innovative writing across the last several decades (Sarah Dowling, “Ethnos and Graphos”); the markers of race in contemporary localities and the work of one of the chief practitioners of High Modernism, Wallace Stevens (Aldon Nielsen, “White Mischief: Language, Life, Logic, Luck, and White People”); and the connective seams between Middle Eastern poetry and “transcendental lyric” in the contemporary US (Leonard Schwartz, “Transcendental Tabby”). Dowling interrogates the ways in which the nonliterary forms of ethnographic inquiry and poetics meet in work by Gwendolyn Brooks, Cathy Park Hong, and Garry Thomas Morse and provide an important challenge to models of power and privilege that Dowling argues perpetuate modes of oppression and silencing, cultural formations that can be addressed if not entirely dismantled through the conjoined activities of poetry and poetics. Leonard Schwartz, on the other hand, pursues a course of study that has us consider the ways in which the “transcendental mobility” of language (in this case Arabic) reconceives poetry as a form of subversion through its pursuit of “a language within a language” that thereby alerts us to other formations of the social and the transnational, thereby mobilizing poetry’s unique ability to both challenge and better comprehend cultural difference.[19]

Of these three, perhaps the most provocative is Nielsen’s essay that focuses on Wallace Stevens’s blatant racism in a poem such as “Like Decorations in a Nigger Cemetery” (this poem has received little critical attention across the years, at least insofar as a search on JSTOR suggests). Nielsen opens and closes his essay with anecdotes that usefully highlight both “white mischief” (a form of social reality that demonstrates its racism in covert or under-seen ways) and the rhetoric of white privilege that undergirds it. In so doing, he provides a useful corrective to any reading of Stevens that would have us look past the racist ideology explicit in “Like Decorations in a Nigger Cemetery.” Nielsen’s repositioning of perspective, one that focuses particularly on the work of Jacqueline Brogan and her defense of Stevens in The Violence Within/The Violence Without: Wallace Stevens and the Emergence of a Revolutionary Poetics, carefully unpacks the ways in which Brogan’s reading, meant to rescue Stevens from charges of racism, only reinscribes the same racist discourses and becomes a concomitant erasure of “the actual black people in an actual America.”[20] While Stevens’s racism, like that of Pound’s anti-Semitism, may not come as a surprise to many readers, Nielsen’s proscriptive reading of Stevens provides a sharp reminder of the racist ideologies at work in poetry produced by any number of white writers otherwise shielded by their perceived canonicity and the ways in which such racism continues to exert its “mischief” in all sectors of the culture, including but hardly limited to academia.

The essays that close this volume fall under the title, “Digital, Capital, and Institutional Frames.” As such, they query what the editors term the “large-scale inhuman forces that exercise their powers somewhat indiscriminately of the people and societies they affect.”[21] Capitalism and its effects, vis-à-vis technological reproduction, consumption, and market force realities, bring forward responses by Ron Silliman (“The Codex Is Broken”), Vanessa Place (“Empire Aesthetics: It’s Not the Point, It’s the Platform — Detroit Model”), and Brian Reed (“Now That’s a Poem: Vito Acconci, Conceptual Writing, and Poetic Nominalism”). The interventions here vary from Silliman’s argument that we need to have a more nuanced understanding of the shifting publics for online and other electronic platforms that deliver poetic content today; to Place’s deployment of multimodal formations of popular culture and conceptual artworks that begin from the idea that “all art is now site-contingent”[22]; to Reed’s inquiry into conceptual poetries that stand apart from normative considerations of the poem and the ways in which we need to think differently about how and why we confer upon some literary artifacts the descriptor of poem but not others. Reed includes in his analysis work such as Craig Dworkin’s Parse (2008), whose effort is to deploy the syntax of a grammar textbook as the basis of a poetic text, Kenneth Goldsmith’s Day (2003) and The Weather (2005), the latter consisting of radio weather forecasts written down with minimal changes across a year. In so doing, Reed argues that conceptual work such as Goldsmith’s and Dworkin’s extends the ongoing conversation in the language arts communities about forms and models of agency and production that challenge preconceptions of what a “real poem” is, looks like, and does.

This closing essay of Inciting Poetics, with its emphasis on conceptual responses to the poem and poetic practice, also highlights one of this volume’s key omissions already discussed: extended treatment of and responses to and by writers in the Black innovative tradition. Reed’s focus on Goldsmith in particular raises troubling questions about the position this volume takes (and doesn’t) on work like Goldsmith’s characterized by a refusal to acknowledge its own white privilege. Goldsmith’s 2015 performance at Brown University of “The Body of Michael Brown” is notably absent from Reed’s take on the conceptual platform Goldsmith occupies (even taking into account the time lapse that may have occurred between Reed’s writing of this essay and its publication in this volume). Goldsmith’s reading from the St. Louis autopsy report of Michael Brown, a teenager whose killing by a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, helped galvanize the Black Lives Matter movement, arguably co-opts and objectifies the Black body and the experience of Blackness from a position of white privilege to a predominantly white audience. The controversy surrounding Goldsmith’s reading is quite rightly something that should have been addressed in this closing essay that considers what Goldsmith’s poetry incites and for whom.[23]

If this collection isn’t conclusive in its findings or always clear on the cohesion of its vision (arguably, it sets out to be neither conclusive nor cohesive), Inciting Poetics seeks to bring us closer to different strands of contemporaneous thinking about poetics in twenty-first century contexts and the value we place on such work. In this respect, this volume largely succeeds, falling short in ways already noted here. In creating a forum for something other than aesthetic reactivity and localized disputes between and among factionalized poetic communities, Inciting Poetics scans the disparateness of our present with a strong foothold in antecedent models and provides variegated evidence about poetries and the poetics that remain in conversation with that work. As Tyrone Williams points out in the coda to this collection, “The United Divisions of Poetry,” our very conceptions of what constitutes mainstream, what constitutes marginal, have become intricately wed to an evolving landscape of “media, libraries, bookstores (online and ground), mythologies, and historiographies that constitute, transmit, and reinforce the very concept of poetry.”[24] Williams argues that we have moved from any settled lines of demarcation to a territory marked by Occupy Everywhere, as poetries have functionally inserted themselves into all facets of the culture as former categorizations such as center/periphery, mainstream/experimental have effectively lost their meaning. The result is a cultural context in which we are witnessing “a blurring, if not erasure, of the private and public, an existence out in the ‘street,’ inhaling fresh air among the ‘people.’”[25] For Williams, the salient element here is the dialectical process whereby poetry stays new through its continued rejection of institutional co-optation. In this way, Williams argues, poetries of the twenty-first century borrow from tactics and strategies of prior eras, but do so in ways that transect an ever-more open social space that has become “a mode of street theater.”[26] And, as Williams goes on to observe, while we may not be able to gauge the effectiveness of any one aesthetic strategy or response to cultural pressures placed upon poetic production, this tenuous contingent space remains our “ground of responsibility.”[27] In this sense, George Oppen’s equating of poetry with a “test of truth,” cited by DuPlessis in her “Statement on Poetics,” has never been more contested nor more important to consider in the shifting historical, political, and cultural landscape where the poets featured in Inciting Poetics must do their work.

1. The New American Poetry, ed. Donald Allen (New York: Grove Press, 1960). Allen’s anthology, itself a product of profound cultural shifts and rethinking of what constituted poetry ca. 1960, has become in the decades since its publication a canonical text of innovative poetry and poetics in the US, notable for its publication of a diverse range of poets otherwise off the radar of New York trade presses and universities dominated by the New Criticism. Among the poets brought to the attention of a wider reading public through Allen’s anthology were Robert Duncan, Charles Olson, Robin Blaser, Jack Spicer, Madeline Gleason, Helen Adam, Philip Lamantia, LeRoi Jones/Amiri Baraka, and Larry Eigner. As Alan Golding remarked in 1998 on of this anthology, initially intended to last a few years before another came along to take its place, “it retains enough staying power as an anthological touchstone for alternative poetries that editors of avant-garde anthologies continue to invoke it as a model over thirty years after its publication.” Alan Golding, “The New American Poetry Revisited, Again,” Contemporary Literature 39, no. 2 (Summer 1998): 181.

2. Jeanne Heuving and Tyrone Williams, introduction to Inciting Poetics: Thinking and Writing Poetry, ed. Jeanne Heuving and Tyrone Williams (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Pess, 2019), x.

3. Heuving and Williams, introduction to Inciting Poetics, x.

4. It’s interesting to read Ron Silliman’s comments to Bruce Andrews in a letter from 1971 in light of the focus Heuving and Williams give to the influence of Language writing in the framing of the essays included in their collection: “All this (whatever this is) is at the experimental fringe of Caterpillar and Paris Review areas. Altho the fact of it disturbs me. The dichotomy itself is silly, but real because imposed not only externally (like the Allen anthology), but by internal elitists: Eshleman & Padgett & Shapiro are the best examples.” THE L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E LETTERS: Selected 1970s Correspondence of Bruce Andrews, Charles Bernstein, and Ron Silliman, eds. Matthew Hoder and Michael Golston (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2019), 32.

5. Heuving and Williams, introduction to Inciting Poetics, xi.

6. Heuving and Williams, introduction to Inciting Poetics, xi.

7. Heuving and Williams, introduction to Inciting Poetics, xvi.

8. Heuving and Williams, introduction to Inciting Poetics, xvi.

9. C.S. Giscombe, quoted in Aldon Nielsen, What I Say: Innovative Poetry by Black Writers in America (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2015): 2.

10. Lyn Hejinian, “An Art of Addition, An Eddic Return,” Inciting Poetics: Thinking and Writing Poetry, ed. Jeanne Heuving and Tyrone Williams (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2019), 8.

11. Rachel Blau DuPlessis, “Statement on Poetics: Pleasures, Polemics, Practices, Stakes,” in Heuving and Williams, Inciting Poetics,13.

13. Charles Altieri, “Poetics Today,” in Heuving and Williams, Inciting Poetics,54.

15. Jeanne Heuving, “The Material and Medium of Language,” in Heuving and Williams, Inciting Poetics, 66.

16. Elisabeth A. Frost, “Toward Transformation,” in Heuving and Williams, Inciting Poetics, 85.

17. Cynthia Hogue, “‘To Make from Outrage Islands of Compassion,” in Heuving and Williams, Inciting Poetics, 107.

19. Leonard Schwartz, “Transcendental Tabby,” in Heuving and Williams, Inciting Poetics, 159.

20. Aldon Nielsen, “White Mischief,” in Heuving and Williams, Inciting Poetics,145.

21. Heuving and Williams, introduction to Inciting Poetics,xviii.

22. Vanessa Place, “Empire Aesthetics,” in Heuving and Williams, Inciting Poetics, 193.

23. For responses by numerous writers in the US literary community to Goldsmith’s reading, see CAConrad, “Kenneth Goldsmith Says He Is an Outlaw.” See also Jen Hofer’s lucid response to Marjorie Perloff’s Q&A at the ArtWriting Festival in Aarhus, Denmark on December 6, 2015, during which Perloff describes the public reactions to the death of Michael Brown as “romanticization” based on “pictures you saw [in which] he looks like a little kid, [whereas] he was a three-hundred-pound huge man. Scary.” Finally, for an excellent gloss on representations of race in the avant-garde, see Cathy Park Hong’s “Delusions of Whiteness in the Avant-Garde,” Lana Turner 7 (November 2014).

24. Tyrone Williams, “Coda. The United Divisions of Poetry,” in Heuving and Williams, Inciting Poetics, 228–29.