A vacancy one knew

Or: shallows of content; or: casuistry

A Worldly Country

A Worldly Country

The paradox of the poetic sign is that the more densely textured it becomes, the more it expands its referential power; but this density also turns it into a phenomenon in its own right, throwing its autonomy into relief and thus loosening up its bond with the real world. — Terry Eagleton, The Event of Literature

I have chosen this book / simply because I happen to have come upon a copy of it / but I’m taking it to be fairly representative of Ashbery’s later poetry / by which I would indicate the books that have appeared since Flow Chart (published in 1991 / and succeeded by a new book of lyric poetry every couple of years).

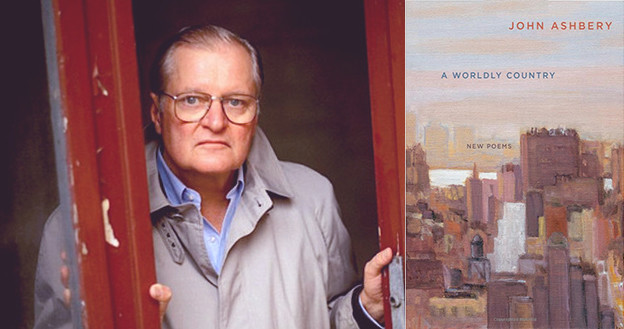

That said / the title of the book — A Worldly Country — stands out as remarkably odd. The only context I have for an interpretation would come from fundamentalist Christian religions / which are wont to refer to the times in which we live / and to the behavior of that time’s inhabitants / as worldly / as opposed to godly. The use of a Jane Freilicher painting on the cover (and against which the title stands) / underscores this intended meaning — for it is a painting looking out over the rooftops of the sky-high buildings of the city / the buildings somewhat indistinct / the probable reason being the seeming pollution that mounts the sky in the background. When apart from the book itself / its title stands for it — for example in a list of books by the author / or (should the book become well-known) in the memoried imaginations of generations of readers — a book’s title is of some considerable import.

The book is dedicated to Barbara Epstein / born a year after Ashbery / died the year before A Worldly Country was published / a founding and longtime editor of The New York Review of Books. Did she / too / live in a worldly country? / Has she now left a worldly country behind? Certainly / the dedication would seem to slant the intention (the focus) of the book at least slightly (or perhaps it merely turns that attention down) / toward the literary world / which can only be seen to inhabit (a very small part of) the larger city / and the worldly country in which all these reside. The title frames the book — its dedication focuses it.

“If it occurred / in real time, it was OK, and if it was time in a novel / that was OK too.”[1] I’ve chosen these lines from the first (the title) poem of the book / because they bear a passable relation to what I have already found the title and dedication to (begin to) suggest. The rest of this first poem would seem to describe nothing so much as an armistice after long war — although it is described (in rhyming couplets) in terms more suitable to the tunes of a child’s merry-go-round in a friendly park — everything is rather buoyant and puffy (cotton candy / perhaps) — there is little to prepare us for the final “And just as waves are anchored to the bottom of the sea / we must reach the shallows before God cuts us free” (1). This denouement of the page-long poem / is almost frothy in its acceptance of whatever has gone before (what were those horrors / anyway?) / which are themselves only mildly undercut by that before God cuts us free. Another way of getting at this (or trying to / anyway) would be by way of noting that the images in the whole of the poem do not cohere — we could not with accuracy say that they are incoherent / because they are not — they hang in relation to each other / like what? — I can’t with deliberateness say — perhaps like that “crescent moon / hung in the sky like a parrot on its perch” (1). The items of information / as they progress / from and through the poem / are here almost all images — images to which the language then attaches as a tone. The images do not mount up to be things (like things do) — they stand each in at least somewhat tangential relation to all the rest — they are nowhere grounded / or purposeful / so that those last lines of the poem with God in them / come upon us unexpectedly / and (if the tone is to be believed as inference [ as I believe it must ]) with at least as much unexpectedness as upon that God.

The meaning (then) is not feasible. It is offered up / leftover bonbons thrown to the chickens and geese / for our brief notice — it offers us (us [ it offers us ]) nothing (save that brief notice?) in return. The language is fluid — it nowhere adheres to the page — it is something that happens (almost without our noticing it) / and (but for the poem) would go unnoticed / unresolved / of no help. It is (finally) as if the poem had not managed to notice itself occurring.

To make such a stance possible / the language has to be contrived to hang very loosely in relation to the world (The world is all that is the case.[2]). Whatever the poem might be saying / by using language of this sort with which to say it / it leaves it said / or unsaid (it little matters) / before it dips with its slight bit of negativity and is gone. The whole thing — a sort of bashful / but unabashed / curtsy — in the face of whatever it is that contrives to come to pass.

The poet (here) stands in some relation to the world (that seems to be what the poems are saying) / but his poems do not. They are faded to be devoid of reference (or very nearly so) — so that they leave the poet (their [ their ] poet) standing alone / somewhere off there in the corner / without the solace of the poems that he thought he came in with (I’m already resorting to Ashberyesque imagery! [ the referred-to arabesque is intention / an exact mention of how these poems manage to resort ]).

What does it mean to be in a room full or signifiers (in a city full of them? / in a worldly country redolent with their abstractedness?) / but with not a referent to be seen? / or with some seeming referents seemingly somewhere nearby / but with no connection between the two (the many)? It means that there is no necessity. There is nothing there (not really) / nothing that we might find needs putting in its place / and there is (anyway) nothing very much like a place either — so (you see) the ambient lack of need. Perhaps this is being done so that there is no loss (so that there will be no loss) — after all / if no meaning is being committed / there is (apparently at least) nothing much of anything to be lost — but neither is there a commitment / neither is there a single act of discernment / neither is there anyone (not really) saying this is thus and so / and we could think about it this way / and (if we were to get up off our nonexistent sofas) we might find that in order to make things be some other way (for the good of some others [ say ]) / we would have to begin to write so. We would have to turn wording into doing (of other sorts / as well) — but / we are a long way off from anything like that here — here we are inhabited by a kind of haze / one that surrounds us even as it fills us / such that there is not really any tangible difference between our insides and our outsides / and (then) there is nowhere any median to be bridged / no need for language really (not here / where there is nothing (left) to say). It is so passive / so inexorably not (not) committed (so inexorably not committed) / that it seems to be saying — really / no / not / nothing / really / nothing / but no / I didn’t mean to say that / it was nothing / really / really nothing.

This kind of dead end in discourse found an eloquent spokesperson in Beckett — its effect was shown to us with forceful clarity in the images made by Giacometti. What is unsayable / finally / is what has (has [ what has ]) to be said — to not (not [ to not ]) say it / is to die — is to kill (really). “What we couldn’t see was / delightful” (2) — really? / are you buying that? The questions that he asks are not even redundant / are not even not (not [ are not even not ]) intended for answer — neither do they stand in relation to anything else / least of all to anything else in the rest of the poem (in which they [ would have to be said to ] occur) / where they seem rather like just a slightly different sort of line stretched somewhat differently between two nonexistent (but somehow adjoining) points. This language does not support this language — it everywhere lets it down. It’s pretty.

Little Wedgewood figurines / slowly revolving / without regard to even relationship / certainly out of all regard for revolution (of either sort) — or / perhaps they’re not revolving / perhaps they’re not revolving after all — and it is (rather) just a trick of the language / a trick of the language having been made to itself revolve / such that other things would seem (would seem) to be. A slow turn in a drawing room / absent and absented — and then / gone / or. Very polite.

This writing turns down the future. It has nothing to do with it whatsoever. The word / the concept / doesn’t come up. There’s no communion — there’s nothing that people do together / nothing they might argue about / nothing they might find it better to do something other than — there is no possibility / because there is nowhere anything like a ground upon which such a time (a time to come) would stand (would occur). There’s nothing to worry about / not even the slight bit of worry that seems to be constantly haunting us (in these poems) — that little bit of worry that is used to give the words and their eventual turnings just that little edge / that as-if (as if [ that as if ]). But / how can there be even that? / how can there be an as-if / without an is? — There can’t / or / there just doesn’t seem to need to be — not for now / anyway — not here / where there is no now / nor ever will be. It is abjection without position / or passion. Abjection / alone / unto itself / itself alone. The words don’t count.

*

We could speak of Ashbery’s later works in this way — using music as a metaphor / we would say that tone is much more apparent than melody — using painting as a metaphor / we would say that hue is much more important than color.

I admit that the work is not without the linguistic equivalent of melody and color / to some extent — there are at times intimations of melody behind tone / and there are at time hints of color behind hue — but those occurrences are far from being the norm. The poetry is soft / evened out — lost in itself. One notices the considerable extent to which it is redolent with a plethora of affect. The ratio of surface to content is extremely high.

*

There is a great deal of reticence in this writing. There is a reticence to speak / to say (to say) something (to say something) — there is a reticence to use (use [ to use ]) words.

It’s almost as if he’s been pushing the words around the page to see what kind of trail (what kind of trace) they might leave behind.

*

Ashbery’s poetry is inherently lackadaisical / lax. The same or similar words in a different order (they would be in a different order) in a poem by say O’Hara would have an essential thrust forward (in whatever direction) — they would remind us of life / and to live. In Ashbery’s hands the words form poems that are essentially desultory when even at their most bright.

The lines move with a kind of mellifluous gentility (there is no denying that) — but that mellifluousness is almost solipsistic / almost as if each line is flowing back over itself / rather than going on — there is no quest.

*

A mellifluous sonority — it’s not that that’s what inhabits these poems — it’s more than that — it’s what they’re made of / it’s what they are (are [ it’s what they are ]).

An almost de-evolutionary amount of listlessness! It’s as if the language is being unwound — unused (un-used).

His lines are liquid — they’re made of water / sometimes turning itself slowly into vapor — there’s never anything sold / never any fire.

*

There’s a lack of discernment that determines the extent of these. They are primarily moody.

When I say that there’s a lack of discernment / I say that there’s nothing much here about the world at large — about how it’s made / how it operates / who makes it run / who suffers and who doesn’t / who will survive and who will not. There is not here the kind of information that we need to keep us alive. There is a docility / a lot of docility.

[ I won’t say that I don’t enjoy reading the poems. In a way / and to an extent / I do — I enjoy reading them rather the way I enjoy watching a windshield wiper clean the rain off the windshield (not for long / for limited effect). ]

Occasionally a line rises to the occasion (and to say that is to say rather a lot) — but then the next one or few sloughs off into a kind of diffuse surrealism / soft images brushing up against one another — the original impulse (to say something [ if it was that ]) now long gone. They do express something — the lines express a kind of a feeling — but always something at one remove / and then at several / from what might have been said / had saying anything been the intent (or even close to it).

What if we are all ignorant of all that has happened to us,

the song starting up at midnight,

the dream later, of lamb’s lettuce and moss

near where Acheron used to flow. (5)

Here / even the Acheron / instead of being a proper noun / and used as such (i.e. / something solid put in place / and made to be there) / is used instead to let the original impulse (if that it was) flow on and off (but / to nowhere). Perhaps it is / in some way / rather blissfully consistent with the Via Negativa (that occurs earlier in the poem) / but it is a kind of consistency (if it is a kind of consistency) that washes itself clean — a self-negating non-negation (as it were).

The poems provide rather a nice place in which to go to sleep. Critics of this work have sort of moved in / and furnished the walls of the poem (soft and deep as dream itself) with their own ideas — and then (and only then) / taken those ideas to be the ideas of the poems themselves — it is not difficult to see to what an extent / or in what ways / this activity is bound to be boundlessly pleasing to the critics thus engaged (what self-affirmation! / at the expense of the little that was really there [ if it was ]).

There are / as it turns out / lines that appear to have the metaphysical about them (if not to be actually about [ about ] the metaphysical) — but the metaphysical / even the metaphysical / is rather long-gone from the scene — what we are experiencing is (instead) its echo / or the echo of its aura / or the scratching it made on the sides of nothing as it went. And always this evasiveness — this massive evasiveness.

Can we say that it is about what can’t be said? — can we say that? No — we can’t say that. It is about / if it is about anything / itself — it is round and about itself (but most often / not even quite that / not even quite there).

Much will be forgiven those

on whom nothing has dawned. (8)

At least there’s nothing here to stir anyone up / or to get them to do anything (!). It’s all rather more like a massage (if that) / a massage for some phantom pain (if that).

We could ignore the warning signs,

but should we? Should we all? Perhaps we should. (9)

In the interstices / things do get said — mostly about the interstices / as if only the gaps between what matters matter. This offers a kind of comfort / particularly to those who don’t know / to those who don’t want to know / and particularly to those of them who are satisfied with that. There’s even a kind of encouragement — seems to be a kind of encouragement to not exist / so as not to bother anyone else (who has already been encouraged in their nonexistence / and have [ apparently ] stuck with it).

The dominant mode is irony — a soft irony / being ironic about itself. That mode / that gesture / is repeated in Ashbery’s poems again / and again and again — and that’s all / or almost all (we’re no longer sure which / and [ we’re being told ] we don’t need [ or want ] to be).

I guess what I’m saying is

don’t be more passive-aggressive

or purposely vague than you have to

to clinch the argument. (16)

So there is / here / occasionally / (at least) a kind of self-awareness. That’s what irony is / after all / isn’t it? — the language’s rather embarrassed self-awareness. Of course it can be used for more than that / irony can — but here it is content to just be itself / to just be (rather apathetic / rather sad / totally irresolute / out to do nothing / contented [ in that sad way already mentioned ]). It’s as if nothing is going on in the world (really) / nothing at all. Even the sadness isn’t real sadness — it’s just the sadness that the sadness is suggesting to itself (kind of) — much more a whimper than a fact (an act) / more a yawn than a whimper.

*

Perhaps it is (in part) the passivity implicit in producing primarily masses of poems that have no more reason for being in one book than in another one / that creates (or permits) Ashbery’s relatively vaporous style (tone / manner / substance). When a book is made as a book / it has internal structure / rigor / underpinning / braces / and so on — it is quite probable that having these effects, the material that is being written does also.

*

In addition to the poets one has at times been influenced by, there is also a much smaller group whom one reads habitually in order to get started; a poetic jump-start for times when the batteries have run down.[3]

Ashbery devoted his Norton lectures to a treatment of poets who have served him in this way.

I am familiar with the fact that younger poets / poets when they are fairly new / use the reading of other poets who have gone before as something to work off of / something to inspire them / something to get a new poem going. It seems odd to me that a senior poet should still be working in this way — if this fact / that his writing is (at least at times) written in relation (in response) to other writing / rather than out of other sorts of lived experience / it might account in large part (in some part?) for the rather effete nature of what Ashbery has been writing.

*

Am I being harsher in my critique than I need to be?

Yes — somewhat.

Occasionally there is a poem — one in seven? / one in nine? / a part of one here and there — with a little more cognitive material to offer — a little more meat on the bones / a few bones in amongst the meat and fat. But not more than that.

*

Ashbery’s verse stands in opposition to objectivist poetry / in at least a couple of ways.

His poems are not objects — they are rather more like a plasma / without skeletons either exo or endo. These poems are (at least relatively speaking) lacking in structure.

Objectivist poems / at least the ones that live up to that name / are objects. They’re durable. You can tell that they’re made out of words / and that the words have been set in a particular place for the particular reason only that place would satisfy. However, Objectivist poetry is not cold. As Zukofsky wrote — “Only emotion objectified endures.”

Objectivist poetry is also very clear / and very clear about having a message. Ashbery’s work is entirely subjective / to a fault. Its message / repeatedly / is the self — what the self is feeling / what the self is doing and / most often / the flow of words passing through that self. It is an efflorescent effluvium.

*

Thoughts try / here and there / to obtrude — but are given short shrift by the language that everywhere overclothes them. Why don’t they come in their own language? — they can’t (not allowed). They have to be all dressed up (you see) / to be going somewhere — which gives rise to the occasional sad / limp / (sadly limp) / joke / about there not being anywhere for them to go (really) — sardonic slyness being a dominant tone here.

Actually / waste deep in solipsism / what would a body do with wearing clothes to go about in (anyway?). “The wraparound flux we intuit // as time has other claims on our inventiveness” (79).

*

Occasionally / some kind of statement manages to arise —

Some experts believe we return twice to what intrigued or

scared us, that to stay longer is to invite the egg

of deceit back to the nest. Still others aver

we are in it for what we get out of it, that it is wrong

not to play even when the stakes are spectacularly boring,

as they surely are today. (9)

But these moments of proffered wisdom are few / and far between — and they are usually surrounded by a plethora of soft images / softly undulating.

In other words / there’s a sort of philosophical language / from time to time / and there is a language of image-infested phrases — it is just possible that the latter are allowed to rise too freely / to inhabit spaces that boredom or ennui makes available to them / that they need to be checked. But then the more ruminative language would not stand out from anything else / would (in any case) be little more than merely rather flat.

There’s also a kind of aw-gee-shucks language / that occurs as phrases —

but sometimes they get, you know, confused and

forget to stop when we do (15)

That sure was some summer. (16)

Oh well, less said the better, they all say. (60)

This sort of language serves to identify the poems as American / and I’m rather grateful for it when it does occur — they are a kind of pop moment / kind of forcing its way in. Pop art emerged in the ’50s / as did Ashbery’s poetry. However / pop art reacted to abstract expressionism — Ashbery’s poetry created it.

*

There is a kind of slight surfeit / here / of feeling. The feelings are almost all almost dangerously languid — they seem to be waiting for nothing to happen. It’s as if he is afraid to confront anything directly / and so always disenjoys the sensation of being lightly / and repeatedly / slapped in the cheek / by life (by what life proffers [ by what life has to proffer ]). There’s a kind of complaining going on / a whining (in fact) — “Wheedle on for just a little bit” (21).

And always / there is the impression being given that there is nothing to be done / nothing / nothing whatsoever / not now / not if / not when / not ever. This may even be true — I mean / one could even mount a defense for it as some kind of moral stance vis-à-vis the extant miasma — but it is not a solid ground for poetry / it is not a solid surface upon which to build with words / and it leaves us (if it is / indeed / an us) again / with nothing to say. The fact that the world doesn’t seem to offer any solutions / to anybody / of any of its problems / is not reason for silence / and (even less so) for near-silence (which can only rancor / as it is (here) seemingly / and repeatedly / intended to do).

Saying something / always makes it possible to go on saying / something else — but that’s no reason to say it.

*

Perhaps he is saying what he most exactly means / when he writes —

Nobody needs to know what is ailing me,

which is sad, but telling them would be worse. (25)

or —

The tunes here are overstuffed,

the lyrics threadbare. (30)

The lines are not even struggling.

Ashbery’s entire poetry exists to keep a certain attitude alive.

If you wish to live in an entirely noumenal world / with nary a phenomenon in sight / then you can pass some time here / for a while. But you won’t be given much / or left with much to give.

*

Ashbery writes as if it’s his way of reading himself back into the present moment.

It’s as if he could be resuscitated / or (thinks he could) resuscitate / with tone (with tone alone).

And his tone is always impeccable / very much as if it had need of nothing else. He offers tone / everywhere / in place of the actual. Admittedly / the actual is a hard thing to hang your hat on — but that is not to say that it can’t be done.

This language never takes offense — a discreet cough (perhaps) / and then that is that.

Very many turns of phrase.

Very many fine turns of phrase.

*

The poems are all rather stately. To read one is somewhat like entering an ornately appointed ballroom — there’s a considerable amount of space — the eye / and its mind can travel — but the furniture / and its surroundings / do not seem to have been made for daily use.

The fact that these poems are in some ways reassuring / is not a reassuring thing to be saying about these poems.

1. John Ashbery, A Worldly Country (New York: Ecco Press, 2007), 1.

2. See Ludwig Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus.

3. John Ashbery, Other Traditions (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000), 5.