Twenty-two on ‘Tender Buttons’

Tender Buttons: The Corrected Centennial Edition

Tender Buttons: The Corrected Centennial Edition

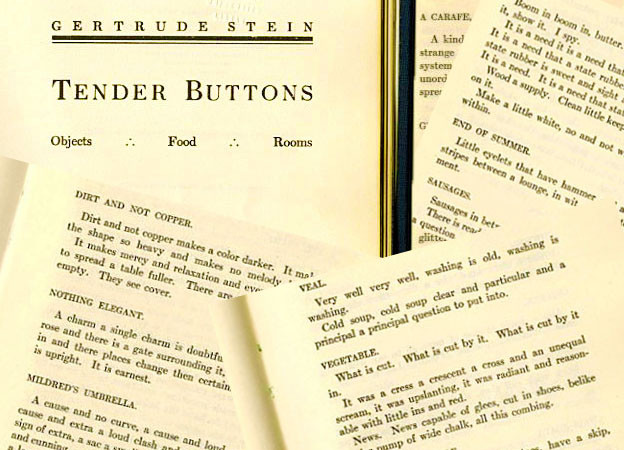

For the 100th anniversary of Gertrude Stein’s Tender Buttons, published in a corrected centennial edition by City Lights Books in 2014, Jacket2 invited a number of writers to pen “microreviews” — short, impressionistic, discursive, or momentary reflections on the book which first appeared in 1914 in a print run of 1,000 by Claire Marie and has been republished since by Green Integer, Gordon, Sun and Moon, and others. Tender Buttons has come to be understood as one of the most important and challenging texts of twentieth-century literary modernism, what Charles Bernstein has called “the fullest realization of the turn to language and the most perfect realization of ‘wordness,’ where word and object are merged.”