Playing Stein

Tender Buttons is the future. Neither cipher nor code, the grammar of Tender Buttons forces the reader to play Stein. Stein’s obsession with perspective, her collection of objects, food, rooms, produces a scene of constraints (the rules of the game): a discrete spatial field where coordinates shift as the text’s gravity swerves. A game board. No, a bored game.

The myth of impenetrability widely ascribed to Tender Buttons is undone by the text’s clever earnestness. Description in Tender Buttons is direct, user-friendly. The game’s logic revolves around the question of who gets it (who gets how). We play Stein and make moves forward.

Kate Huh, “Portrait of Gertrude Stein and Joe Dallesandro,” 2014.

Kate Huh, “Portrait of Gertrude Stein and Joe Dallesandro,” 2014.

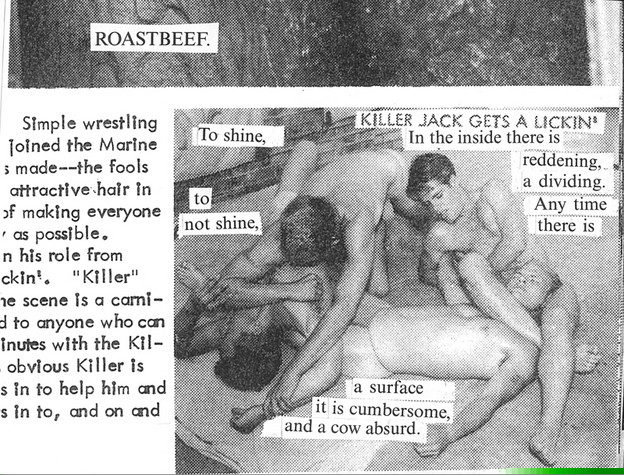

In “Roastbeef,” Stein informs, “it is so easy to exchange meaning, it is so easy to see the difference” (35). Stein’s proclamation may act as ethos for contemporary artist and activist Kate Huh’s collage work drawn from Tender Buttons. In this piece, Huh trick-steers those who “don’t get it” into the supposedly perverse lure of Steinian grammar. What a relief to look at beef, as beef.

In our histories, looking is queer action. Cruising animates desirable objects to the unfolding possibilities of queer futures. Homo echo: Stein’s way of seeing in Tender Buttons animates desirable objects into unfolding possibilities. Cruising is queer seeing, all means and no end: a way to get lost, a game without a goal.

In Cruising Utopia, José Esteban Muñoz describes his methodology as “a kind of politicized cruising” that approaches the queer “from a renewed and reanimated sense of the social.”[1] It’s my sense that Stein, Muñoz, readers — all of us over time playing this game Tender Buttons — are “carefully cruising for varied potentialities that may abound.” When we play Stein, we find new strategies for seeing over the horizon.

Myriam Gurba, "Chilaquiles." Excerpt from Tender Birria.

Myriam Gurba, "Chilaquiles." Excerpt from Tender Birria.

Stein’s queer way of looking in Tender Buttons is an observational strategy that deflects not just center, but self. As she looks over the still lifes of Tender Buttons, she cruises, investing and losing interest in real objects through flat affect. Disinterested interest. Like Warhol, a heartfelt ambivalence underlies this queer obsession with looking. When the artist flattens what is being seen (cubism, dada, pop), the art of looking means to look without being seen.Where are we?

Tender Buttons is the catalyzing force for queer lines of sight in the twentieth century.

Andy Warhol, “Gertrude Stein,” 1980.

One legacy is hope. Queers inherit a twisted revolutionary poetics from Tender Buttons. The game gets replayed again, again in lesbian adaptations because Tender Buttons helps us look the way we already look, see the way we already see. We “see the way the kinds are best seen from the rest.” We see the same in futures: “Hope, what is a spectacle, a spectacle is the resemblance” (20).

Muñoz saw it: “[I]f queerness is to have any value whatsoever, it must be viewed as being visible only in the horizon” (11). At 100, Tender Buttons tilts forward, futuristically, and we get it. We still get to get it privately, in public.

Eve Fowler, from the “it is so, so it is” series, Manifest Destiny Billboard Project presented by LAND (Los Angeles Nomadic Division), 2014.

Eve Fowler, from the “it is so, so it is” series, Manifest Destiny Billboard Project presented by LAND (Los Angeles Nomadic Division), 2014.

1. José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (New York: NYU Press, 2009), 18.