Transitionary framings, a case

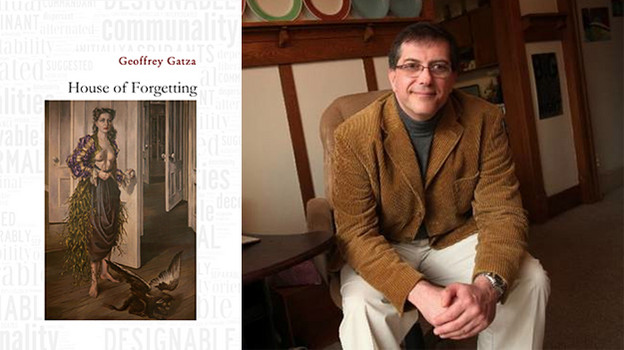

A review of Geoffrey Gatza's 'House of Forgetting'

House of Forgetting

House of Forgetting

For readers of Gatza who have already come to expect the unexpected; for those fascinated with emerging innovation in book-structured polygraphies, then House of Forgetting is yet another contribution to what is becoming a prodigious oeuvre. For those who have come recently to poetry and poetics, or desire a greater understanding of Intermedia poetry, House of Forgetting offers an attractive entrée.

While there is a “heart” to House of Forgetting (human figures with human concerns) and an ekphrastic narrative (the death of a beautiful woman/gifted revenant), there are also elements of language-image that transform temporal and human identity. Such transformations themselves form book “frames”; generate a hypertextuality, (“of moving frame to frame”) as Charles Bernstein notes; an alternative to the perceptual limitations of “frame fixation” and “frame lock.” Such transformations seem to invite the display of “an art of transition through and among [interpretative] frames.”[1]

The idea of elastic, transitionary frames in which material assumes the provisional form of the book is as true of this collection as it is of Gatza’s other work: the five seasons of rewoven myth in Black Diamond Golden Boy Takes Bull By Horns; the hagiography of saints and celebs among word images (coinages consisting of gray-scale mutations and other unique treatments), seemingly aleatory and unrelated, found in Secrets of my Prison House, and the most notable of these may be Kenmore: Poem Unlimited, that four-volume satire on American suburbia, a pataphoric world risen on a foundation of assumptions, fantastic as they are amusing, revealing angles of cultural significance.

House of Forgetting consists of two temporal frames: each interacts with the other in transfiguring human form and identity. The first is “The Twelve-Hour Transformation of Clare,” a woman who morphs into words, and the second section, “Recipe for Water,” is that of an artist who is drawing his wife’s portrait while she is in her deathbed, beginning “Now,” going into the past (“17 Days Ago,” “Last Saturday,” and fragments with similar titles) to conclude with “Five Years From Now” told in the voice of cultural assumption: a radio announcer. The “artist” becomes a reported figure; the “subject,” a fictional image no less real than the figure it re-presents. These are not pairs, but multiples. Their reappearance in alternative contexts suggests, rather strongly, an operative multeity of figures, an ongoing dance with interchangeable partners.

Clare (“after Clare of Assisi,” 26) is, at noon, the “last day of January twenty twelve … staring in her v[s]anity mirror” (12), and the other face she sees becomes, six hours later, the notable American painter and poet Dorothea Tanning,[2] who died on the day the poem begins. Clare is transformed by newsprint, by Tanning’s obituary, and the features attributed to Tanning are hers also:

Her dark hair is a tangled thicket of possibility (20)

This thicket may be seen not only in her hair, but the folds of her dress, like roots, primal, exposed, and tangled, the cover image equivalent of what we find of “her” in

music peace, words, and resistance (26–27).

By “Midnight” (the concluding poem to the first section), Clare has morphed into Tanning, but leaves, in the last line, this disclosure:

Your face was an illusion that lingers still, bless you my darling angle (28)

The subject of the sacred angel of perspective occurs again in the recollection of the artist-announcer’s wife in “Recipe of Water.” On “Our third date” his wife claims that “When I dance for them they see an angle” (32). By this association, the three women — Clare, Tanning, and the artist’s wife — speak for the presentation of their own emergence as shapes of sense; art is technique.

The cluster of surreal images that morph into others, changing perspective in a continual pattern throughout House of Forgetting, absorbs the factorialization of time as it appears (often comically and ironically) in the fragment titles; assumes the space occupied by predication, the syntax of tense, and the insanity of grief derived from thinking in linear time.

Perspective is both subject and result of the surreal shuffle; images that float, collide, attach themselves to others until we experience the reality of continual interchangeability in an atmosphere of the metatemporal, a supra-reality:

… Forgetting

We are all the same, we are one (27)

All human identity may be derived from the same letters of an alphabet. The same may be said of titles, chronological time, even texts. Art has no owner.

There are Dada echoes in the house, the surreal (as seen in the only word collage),

and in the Flarf-like assembly of words,

thanking thankless thanklessly thanks thanksgiving

triggered triggerhappy troubleshooting troublesome

troublesomeness troubling trite trounce triumphalism

zigzag zippy zips zither zithers zombi zombie zombies

zonal zone zoned zones zoology zoom (23)

may easily lead to an incomplete reading, if these word ensembles were regarded as Da-Daesque, or Flarfist alone.

The cluster of words (15) approximate an oval, as might be found in the shape of a mirror, Clare’s mirror, and re-present her transformation into words, the ultimate “Birthday” portrait of her noetic ontogeny. Other clusters (23) convey the frenzy and meaning of her revenant nature; how it is that similarity (their alphabetic closeness) disperses in new morphemic graftings, like those root-tentacles in the cover portrait, the differentiations in her seemingly endless extensions of experience. The displacement of meaning may be seen clearly over six stanzas, and thirty lines, arranged in a similar manner, beginning with Latin and Spanish, moving into French, and concluding in Latvian which suggests the isolation of the subject beyond itself, and thus the frustration of the subject-language, and subsequently, its/her freedom. There remains, among and through the chains of innovation, if not truly original word ensembles (which beg for new classifications), the glimpse of hysteria, and the place it plays in establishing an equilibrium, the way laughter bursts out during the worst of our tragedies, a neurological compulsion, a survival. The last entry:

Ohmigodohmigodohmigod! No, you do not understand, I lived

those moments they are my memories. Not this false vision. It

was Tuesday and hot, and she was cold and we were late. … It

would be painfully banal if it were not her last moments on earth (36)

Among all this, there emerges with some frequency what the formalist might understand, if not accept — dare it be said — as a kind of wisdom, that is with the provision that such wisdom is often irony itself and uttered by the poem’s personae:

… black speckles, words upon words metastasize her body (13)

… the eyes of the living are as clear as the eyes of the dead (30)

The trees are infected and the leaves are turning orange and falling,

[and] To be a great poet, one would have to keep

One’s mouth shut (36)

In the poetry of art perspective, House of Forgetting is itself “an object of pure conception” (11) and extends language in a visual art substance whose dimensions create ongoing multiples of sensory experience, expanding as they do so, and it is in this context that Gatza’s book-“frame” polygraphies continue to absorb, intrigue, and proliferate.

1. Charles Bernstein, My Way, Speeches and Poems (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999), 44.

2. Dorothea Tanning, 1910–2012, had not given a title to her painting, a self-portrait created for her thirtieth birthday and the cover image of Gatza’s collection. When Max Ernst saw the painting in Tanning’s New York studio in 1942, he gave it the title “Birthday.” Tanning and the surrealist became lovers shortly thereafter.