Song is remedy for loss

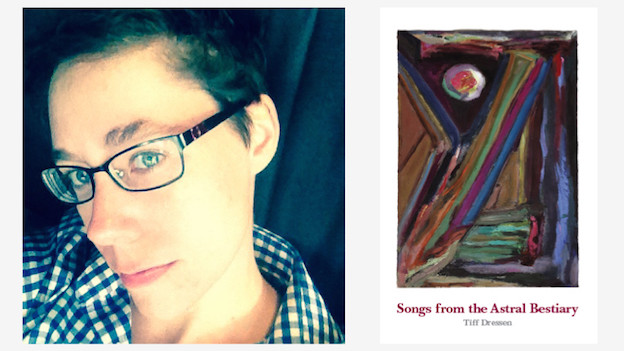

A review of Tiff Dressen's 'Songs from the Astral Bestiary'

Songs from the Astral Bestiary

Songs from the Astral Bestiary

If I were suffering from some kind of loss in the ancient Hellenic world, I could travel to an Asclepion priestess at Epidaurus and spend the night in an abaton, or sacred space, to ride out my dreams after having been given a “sleep” cure suited to my specific needs. In her first book-length collection, Songs from the Astral Bestiary, Tiff Dressen devises her own abaton made of poetry, taking her reader on a lyrical journey via the dreamscape where song is remedy for loss. Staring into the rich mulberry blue, gold, amber, green (and other colors in-between I can’t find names for) brushstrokes of Fran Herndon’s “Triangles,” the cover art, the reader is transported to a world half here, half there, and by the end of the collection realizes that s/he came to “harvest” light too as that “animal / in whom nothing is lost” (52) found in dream.

Offering twenty-three poems, the collection delivers a series of messages (“Message: O you who are” … “Message: book of debris”) and among those, interspersed, are several longer serial poems whose titles suggest propositions with their use of subordinating conjunctions: “If the air we live on,” “As deer (in aurora borealis),” and “Because Icarus-children.” Employing the medieval compendium of the bestiary which depicts animals and mythic animals in their natural history accompanied by moral lessons, Songs from the Astral Bestiary presents bees, deer, “Wapitis,” a “canadensis,” bears, a “trance- / horse,” cannibals, owls, and the hauntingly elusive half-light-half-human “Icarus-children.” The poems, projections from the dream world whose messenger “came to harvest / light” and “to hear the thousands / who signify the future” (2), are in part prayer, incantation, oracle, and their admonitory tone adds a touch of prophecy. Songs from the Astral Bestiary isn’t a first collection that strives through the cadence of language to get somewhere; this is poetry whose songstress has already been there in the “sky-trough” (14) and has returned with the goods to share with “all messengers on their way to / or returning from.” The poem “Message: astral bestiary” appears on the page in fragments as if received from an etched stone shard in antiquity:

cerulean dirigibles

egrets

falcon gestations

helicopter ignitions jamming

LIMA

MACEDONIA.(22)

Dream interpretation as therapy, when “words once were / healers of the sick temper” (27), is a possibility in the hermetic poem “Because Icarus-children,” which opens with a quote by the Danish poet Inger Christensen, “in greylight, indeed they will / exist, in- ” (24):

Because we believe in the whole helio

centric gaze in the sky as house

of the dreamer

Because of the Ionian sea and

the Ionian scar we ask the absent

body to be restored to the present heart. (26)

The poem’s rhythm is driven by the repetition of the subordinating conjunction “because,” and its continual use of the collective pronoun “we” makes us, as readers, also feel (strangely) that “we are halogens” (25), having traversed the poem and having “perceived light / the natural body can never / account for” (27). The reader senses healing at work, and in awe, entranced “under fluorescent skies,” attends to it. In another poem, “Message: a theory (song),” the poet-diviner reveals “(our common lung our / communal humming / lung)”(43), further connecting the reader with the “breath between us / we share” (45). The poem muses an array of songs (“a song of water,” “a catalytic song,” “a pathogenic song”) entering the body through “a staple in the chest / where the song / stuck it / to the song” (43) and, like neighboring poems in the book, suggests that a “song of self-repair” is what “we” have lost. Refining her lyric, Dressen tunes into the Song of Songs that confronts loss. Whether it’s felt in “the oceans’ / lost speech” (2) or clearly stated as “a loss of heart / a loss / of capacity” (43), this first book engages loss by recovering (via dream) a world in which we know “it came from the stars” to share its “harvest” of light. The reader, implicated, becomes other addressed as you who has a “myrrh fairy” (12), like it or not; for you “who are / a creature of / the signs you cannot / escape” (8) are part of the luminary landscape of Songs from the Astral Bestiary, because “finally your face arrived / to complete / the bestiary” (42).

Nomenclature, the system of assigning names to things in the physical world, is explored in several poems. In “Message: It is as we said” (40), the animals are “longing to be,” yet belong “to nomen” as if the weight of their being or desire to be is held subject to (or hostage by) their names: “It is as we said / the animals naming them / we said name them.” In “In your hypoxia dreams” (47), there is someone “learning / how to say / your name for the first time,” and in “As deer (in aurora borealis)” we, “red giant Wapitis” or “cannibals,” name us “nameless” and “name us useless and / distinct” (18). What does it mean to be nameless or anonymous, and who listens when we “CALL ALL THOSE / BELONGING BEYOND / NOMEN / CLATURE” (8)? In “Message: periodic” (9), the immediate poem that follows this “CALL,” the poet-messenger shares, “there is silence however there is / whenever you are speaking / with another,” and then within the same line in italics sings, “silence is the third / and that is me.”Interpreting “silence”beyond the dream or words (naming it) is best expressed in the forms most of the poems manifest in, some utilizing blank space on the page in fragments or stanzas that are pared down to one-word lines. Silence is “the third,” the poet-cipher avows, mediating herself in the objective third person, as witnessed in “Message: parallel myth”:

She

who

forms

the

third

(in the

intimacy of

deciphering)

offers

you

now

the

second

person

like

a small

fast

horse. (29)

The mostly single-word columnar form slows the reader down to a one-two syllable dance between “she,” the poet-dreamer, and you, “now / the / second / person.”

The poems in Songs from the Astral Bestiary are gracefully chiseled, arriving in fragments, set to an open form and sometimes seeming as if guided by the hand of Barbara Guest (“Message: amber”):

At night she went out

to let the bloodtrees

rest upon

the blue wedged

denial wheel

(collector of midnight-drift

pollen aether).(6)

The only punctuation, like all poems in the collection, is purposefully placed, such as the italics and parentheses in the above excerpt (the “third” voice?) from the poem “for Paul Celan.” Blank space accentuates words on the page, stimulating the visual aesthetic of word placement and line breaks, which heightens the enunciation of words and potentially alters or enhances the poem’s meaning. Sound-play occurs in regular lyric breakouts throughout the collection. “Message: O you who are” concludes with:

creatures

numinous incendiary

abecedary; (8)

and the word-dance continues into the next poem, “Message: periodic”:

au aurum aura

gold chromium cesium

gallium (9)

The blank page transforms into the “night sky” (24) onto which poems are projected, with each word a blinking active star — a night sky, “northward,” that we can “sing starve-white-dwarf-crater-songs!” (19) into.

A recurring motif of gestation forms a delicate membrane that encases the entire collection and is activein the images of vessels (houses, abatons, silos, cauls) or things that contain and incubate life — like the body itself. In “Because Icarus-children,” the poem, with its curious tone of admonition, unveils that “we no longer live in sensitive bodies lit up […] because of a reversed birth a reviled birth” (24), and later we are caught in a “centric gaze” stationed “in the sky” or in the “house / of the dreamer” (26). In classical times, abatons — literally buildings “not to be trodden” — were specially designed dream incubators or sacred chambers where supplicants of Asclepius (god of medicine) could sleep to cure a variety of ailments by way of dream and enkoimesis: an opium or other narcotic-induced dreamlike state. Hints of healing using dreams are riddled throughout Songs from the Astral Bestiary,and in “Message: forms,” are affirmed in a third-person narrative delivered in disjunctive song:

And once

she did really sink:

into an abaton

alba

tross silence

(bee cave) […]

(the interpreter mistook) (30)

Repeated images of a “caul,” the portion of the amniotic sac that holds the fetal head, and a storage “silo” fuse together to generate a déjà vu atmosphere in the alchemical “delphic cycle: (turns),” a poem “along the earth” (34) brewing “with iron” and “gas” that requests, if not implores, its audience to participate in a ghostly act of creation, evoking the familiar biblical spirit of word made flesh:

Someone please bury

the caul

behind the silo

as a blood / word

for the cause

of sound

sleeper earth hema. (37)

Dressen’s Songs from the Astral Bestiary not only reminds us that we, readers, are active participants in a poem’s meaning, but that poetry itself is a collaborative act. The collection opens with a supportive epigraph from Antonin Artaud’s “50 Drawings to Assassinate Magic,” setting up a “Way”(1) through which readers might enter this work, “in nature.” Two poems, “Message: amber” (6) and “Message: telepathy” (31), are dedicated to Paul Celan, proffering him “bloodtrees” and a “blueshiftchorus.” In her first collection, Dressen masters poetry that not only is in conversation with other writers and artists, but does so in a generous way: honoring their work by resurrecting it within her own. Other poems activate quotes from James Wright, “cloister … Closing around / a blossom of”(9), or appear as italicized text as in “As deer (aurora borealis)” (10), which restores parts of the obscure poem “The Wapitis” by Ebbe Borregaard. In this way, the book expands within the local and larger poetry communities byliving on through the “representative / of the other” (39)in an authentic poetics of collaboration’s sublime communion. The collection’s climactic poem, “In your hypoxia dreams,” incorporates quotes from Bay-Area poet Beverly Dahlen’s A Letter at Easter: To George Stanley and text from international poet Eléna Rivera’s Unknowne Land, eliciting the question of who is behind the “I” that speaks in poetry:

“but I want to

descend along the dense,

animate river encircling the earth.” (47)

The poet-sibyl’s arrangement with the ancient Hellenic world of mythology additionally serves as a field of collaboration in which the “lost speech” (2) of the oceans is recovered through psychic connection via the astrally traveled dream. An “Achilles angel” (12) and a “satyr-star” (14) are illuminated in “As deer (aurora borealis),” my favorite series in the collection for its peculiar tones of address: “And so the elk sing / O you and your lumbar ache” (10) and “so name us nameless” (anti-nomenclature)! She, who “tonight and forever I shall be […] your mother lode branch and valley” (12), beckons her reader to join the ride: “ankle light / whip kick open thy mouth” (15). We become Dressen’s mythical “deer” animated in a “diffusion through atmospheres” and her “interlopers” (17) on an uncanny horizon whose “Old World” (18) Christian hues, with their prayerful repetitions of “Blessed are those who breathe and Blessed is she,” commingle with the rapturous “magnetic north” (17) of the “wild iris” (11) pagan.

“Breathing” and the “breath,” as in “Bless our breath sensitive” (16), is both theme and instruction during our song odyssey, prompting us to bethink this most important bodily function, while “belly / breathing” (21) signals toward the tradition of the deep regenerative yogic breath in the “song of self-repair” — a song “we share” during “a long ago event” (20). This ambiguous “event” had me returning back for clues, “to screen / an unknown” (2), long after my first, second, third, or umpteenth readings. The “alchemy” (1) that transpires between poet (messenger) and reader (receiver) in Songs from the Astral Bestiary is aired in the powerful intimacy of the I-You lyric address, fostering “our communal lung,” but also “you begin to see / landscape through the eyes / of a bee” (46) which, by suggestion, convenes the reader with “nature” (1). Engage your dreams to heal the self, this debut collection divinely utters with “pieces of you / in my blood and / in my bones / and together we knew” (59) as synergized invitation. Then we shall dream as Bestiary animals do “in whom nothing is lost” after experiencing these poems over and over, each time taking us a new Way to“or returning from” our past or future, “high on the hips” (60) of the poet with her “10,000 horses” (50) across a wordlit sky.