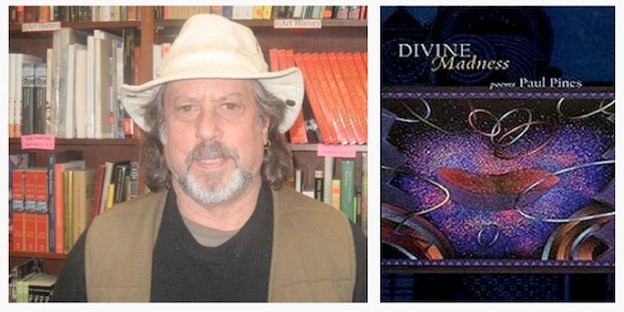

Divinest sense: On Paul Pines

Divine Madness

Divine Madness

Paul Pines begins Divine Madness, his remarkable new volume of poetry, with an epigraph from Plato’s Phaedrus: “if any man come to the gates of poetry without the madness of the Muses, persuaded that skill alone will make him a good poet, then shall he and his works of sanity with him be brought to naught by the poetry of madness. …” Thinking about the title, many readers will also be reminded of Emily Dickinson’s “Much Madness is divinest Sense — / To a discerning Eye —” For Plato, as for the ancient world in general, poetic skill is never sufficient; divine inspiration, or madness, must bring the poetic act to completion. But for Dickinson, living at a time and in a culture where such inspiration was more suspect, the poet possessed of this “divinest sense” risked being seen as dangerous, to be “handled with a Chain —” This volatile dialectic of sense (or sanity) and madness is at the center of Pines’s poetry: not only does it determine the act of writing and the poem’s coming into form, but it is also to be regarded as fundamental to the way in which we think about the world. Thus, in the first poem, we find:

divine madness

encrypting our sleep

like Puritans sniffing out

God’s fingerprints

messages born again

and again from the rubble

of our assumptions

what we listen for

as if decoding

the depth

of a diamond (5)

Such is the task of the poet and his readers: in the modern “rubble / of our assumptions,” we listen and decode the messages inspired by divine madness. The poem is both the message and its interpretation.

Pines’s metonymic reference to the Puritans “sniffing out / God’s fingerprints” proves to be an emblem for his entire enterprise here. The book is filled with figures of seekers and interpreters who, in the course of their quests, challenge the equilibrium of the world around them and find themselves variously cloaked in the mantle of prophecy. As Pines declares early in the book in a poem about Thomas Paine, “we never know what to do / with one who appears from nowhere / to change our hearts” (7). This introduces a crucial theme that will be reiterated throughout the book in various historical, theological, and mythic registers. Divine Madness thus may be read as a serial poem. Allusions, archetypes, historical references, and verbal patterns resonate with each other, gathering force and meaning as the work unfolds. The book consists of forty-seven poems, numbered sequentially and divided into three sections. Each poem is no more than a page or two long. The lines are short, clipped, restrained, set into variously indented stanzas: a projective style but intensely measured, as if the poet is testing each verse as it is inscribed. If this is divine madness, it is being suffered and heeded with the utmost care.

Pines’s fascination with explorers, revolutionaries, and visionaries in nearly all fields of human endeavor — among the figures he invokes (in no particular order) are Columbus, Giordano Bruno, Audubon, Heisenberg, Einstein, and Hermes Trismegistus — may be understood in relation to his view of our struggle for knowledge of both the natural and supernatural orders. This becomes increasingly clear as the book progresses, and is articulated directly in poem 42, quoted here in its entirety:

We create our world

but hide the knowledge of it

from ourselves

for whom

it is meant

a secret

whispered by the Absent One

who holds us together

and apart

the ungatherable

breasts of

desire

veiled by cloud

of unknowing

the living water

of an uncharted land

Columbus

in his madness

mistakes for

Eden (58)

Pines’s trope for divinity throughout much of the work is “the Absent One,” who appears in this instance as a power of unity and division, finitude and infinitude. In the hands of the Absent One, we know and we remain ignorant, hiding our knowledge and creativity from ourselves. In uncharted territory, Columbus suffers a kind of “madness,” believing himself to have discovered Eden. In this regard, all of us are like this paradigmatic explorer in our search for self-knowledge, mistaking our very real discoveries for a mythic Eden to which we may never return.

The Absent One is the God who hides in the “cloud / of unknowing” (Pines refers here to the medieval mystical tract that posits that we cannot attain the hidden God through mere knowledge or intellection) — but the Absent One is also, more simply, the absent human father. In one beautiful poem, Telemachus longing for the lost Odysseus is reinvented as a boy

on a bicycle

hugging his radio

through the late autumn streets

of a mill town

in search of

an absent father

the son of a man

in search of himself

both of them wanderers

in the male mystery (26)

This “male mystery” — the question of masculinity, of how to be a man, a father, a son, and by extension, of how men are to treat women — serves as a psychological and social counterpoint to the philosophical and hermetical explorations that preoccupy most of the poems in this volume. When these concerns come together, the resulting poetry becomes especially profound:

What men enshrine in women

is their own pleasure

no wonder

women resent

what seems homage

to those who

mistaking their impact

and intent

expect gratitude

Men worship in the pink church

of their beloved’s nipples

which they set above

all philosophy

what they need to know

to redeem

the intelligence

that makes sense

of impotence (36)

The “impotence” to which Pines refers is not (or not only) sexual impotence, but the impotence of (male) intelligence in its quest to penetrate both psychological and spiritual mysteries. Pines himself ranges far and wide in this quest; his allusions testify to the way that intelligence propels itself forward throughout history, continually meeting, and sometimes transcending, the boundaries of our unknowing. Thus we encounter

Giordano Bruno

who tried to ingest

the Zodiac

make his mind

a pyramid reaching all the way

to god

burned

at the stake

before achieving the fixed stars (44)

Yet having invoked this saint of intellectual freedom, the poet immediately follows by noting that

Most

alchemists

of the every-day heart

its coagulatio et separatio

punch a clock

drive kids to school

support the weight

of a routine

in which it’s impossible

to understand an emotion

without destroying it (44)

These lines are close to the heart — the “every-day heart” — of Pines’s vision. To accept one’s mundane responsibilities and remain fully in touch with one’s capacity to feel is a challenge every bit as great as the alchemist’s search for the philosopher’s stone. There is a wonderful intimacy in many of these poems, emerging from Pines’s desire “to understand an emotion / without destroying it.” Despite the occasional references to various hermetic traditions, Divine Madness is not an esoteric book. There are many moments here when I am reminded of the lucidity and directness that one associates with the Objectivists, especially Williams, and perhaps to an even greater extent, Oppen, as in these thoughtfully rendered lines:

We ask

our children’s

blessing

require

that they heal us

but all

will fall

on deaf ears

our

words

will be

as leaves

clogging

sewers

until

we learn

to hear them

whisper

in our dreams

in the arms

of lovers

their unspoken

terror of our fear (38)

As a practicing psychotherapist, Pines certainly understands the ways in which we may “ask / our children’s / blessing” and “require / that they heal us”; likewise, it makes sense that he would stress the attention we must pay to our words as they “whisper // in our dreams.” And it is at this point that we come to one of the most important aspects of Divine Madness. The spiritual experiences to which Pines alludes throughout this volume have their roots in the ecstatic performances of the shaman. In his essay on shamanism in Structural Anthropology, Claude Levi-Strauss observes how a shaman treats a patient: “The shaman provides the sick woman with a language, by means of which unexpressed, and otherwise inexpressible, psychic states can be immediately expressed. … In this respect, the shamanistic cure lies on the borderline between our contemporary physical medicine and such psychological therapies as psychoanalysis. Its originality stems from the application to an organic condition of a method related to psychotherapy.”[1] Yet as is well known, shamanic performance is also closely linked to the origins of poetry. As Mircea Eliade notes in Shamanism, “The purest poetic act seems to re-create language from an inner experience that, like the ecstasy or the religious inspiration of ‘primitives,’ reveals the essence of things.”[2] The shaman, the therapist, and the poet all recreate language so that we may again have words for what ails us, and thereby seek a cure. What strikes me as particularly admirable about Pines’s poetry is that his words attain this condition while maintaining the utmost clarity and the most poised lyricism. At age seventy-two, Pines has distilled a lifetime of reading, thinking, caring, and writing into Divine Madness. It is indeed divinest sense.

1. Claude Levi-Strauss, Structural Anthropology,trans. Claire Jacobson and Brooke Grundfest Schoepf (New York: Basic Books, 1963), 198.

2. Mircea Eliade, Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy, trans. Willard R. Trask (Princeton: Princeton University Press), 510.