Nostos — returning home to the self

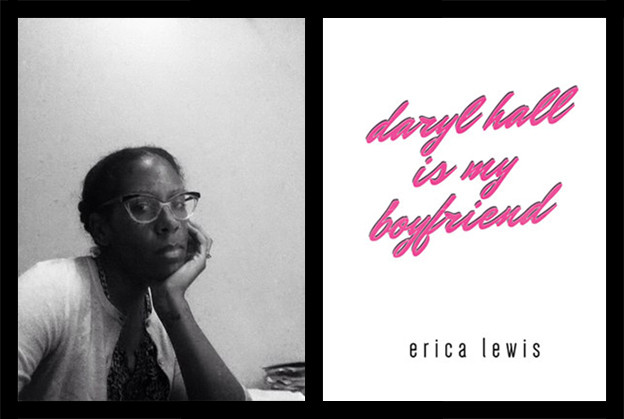

A review of erica lewis's 'daryl hall is my boyfriend'

daryl hall is my boyfriend

daryl hall is my boyfriend

After reading erica lewis’s latest poetry collection daryl hall is my boyfriend, a collaboration that later became the first book in a box set trilogy, I felt as if I’d returned an epic hero who found a way back home to selfhood/personhood via a sea of layered memories, triggered by songs that change “even in the remembering.”[1] Stirring up an accessible feeling of Odyssean nostos, or the journey home, lewis prefaces her collection with “this is an album about re-ordering the past”; anyone with room for nostalgia is invited to join the poet on memory’s dance floor. “It’s about having to grow up. What it means to grow up and let go of the past and childish things,” lewis offers in her “process note.” Constrained by 1980s Daryl Hall and John Oates pop song lyrics, the poet engages memory and spins it through her contemporary confessional.

Memory is a beehive

Organized into three sections, “somehow, you can dance to it,” “instrumentation,” and “rarities and b sides,” the poem titles in the collection all take their names from various Hall & Oates songs, with the actual song title appearing as an asterisked note at the end of each poem. While the poems aren’t about the songs, the songs “trigger” and incite the contents of the poems. Other musical stars from yesteryear also make appearances: Pink Floyd, Paul Young, Lionel Richie, Michael Stipe, the Rolling Stones, Paul McCartney, Etta James, and Patti Smith are included. Songs, and the “stars” who sing them, provide the fluidity that memory thrives on; and as we know, memory never stays in one place, nor does it flow from only one stream. Childhood handclap songs — “apples on the table / peaches on the floor” (7) — interrupt the collection throughout, claiming their position inside memory’s “dresser of small regrets” (7):

we roam in search of a language that can grapple with our multiple

realties including

the delusional one

down down baby down by the roller coaster/sweet sweet baby i’ll never

let you go. (3)

Memory is a “mouthful of bees” (18) buzzing through the mind at thunderclap speed; “childhood glitters” (55) — in which “childhood meant the world was piling up” (54) — and young adult recollection collide with present adult perspective. lewis shows us how the mind operates, moving from past to present, fine-tuning the “white noise” (39) static of time, “and once you admit time past is [actually] infinite / being a child gradually fades away” (5). In the poem, “all the days i’ve lost hoping and pretending*,” the poet begins, “there is a blur between personhood / sitting in this building staring out of a window,” making the path to a whole self a murky one steeped in self-conscious adult mistrust (doubt):

and it was like, forgive me

the logic of childhood is not genuine

i shouldn’t talk about myself that way

in mid-air we forget our feet

we are too old to have this dance party. (65)

In “the stampede / of things that aren’t relevant anymore” (21) there rests an inner assurance that “the heart creates its own history” (30), and included in the pulsating memory stream are both personal and historical wounds, where memory becomes a form of sickness:

or that being alive is a burden inside of you

so memory is just a form of getting sick

the conventional way of saying this suffocates. (65)

Personal wound, and meeting it head on with the hope of healing oneself one day, is confessed in the poem “my bark is much worse than my bite*”:

i know that i’m dealing with some kind of wound

that’s not about losing youth as much as it’s about losing the willingness

i hope one day i will be able to be completely myself. (30)

Sifting through the “anxiety, hope, love” (30) of yesterday and recasting it into a present point-of-view is emotionally arduous; lewis not only brings personal wounds to the forefront to collude with her present, but allows historical wounds to also come into focus. In “i don’t need a reminder of the love that went away*,” the poet shows the receptive (vulnerable?) mind at work, addressing “love” by interjecting the Jefferson-Hemings controversy into the poem as a backdrop, a memory-wound:

love it ain’t for the weak of heart

who writes about a central happiness anyway

there is a new real in my life

and this is like being baptized again

when i think of you and me i’m always worried

graveyards and now the whole

thomas jefferson sally hemmings of it all

you don’t want to think about where you’re from

you want to think about where you’re going. (74)

Yielding to a flash of history, the poet moves forward without blinders “in the process of healing from things in the past” (47). While not directly addressing Thomas Jefferson’s long-term relationship with his purported slave-concubine, Sally Hemings (lewis alters her spelling), a tense historical knot — “what the songs trigger”[2] — surfaces beneath the skin of the poem. The ghostly human wound enmeshes with the poet’s personal history because “we react to pulses without even knowing it” (14) in a constant dance with history’s grand rhythm. And we (readers) aren’t alone; we have an “autopilot” (74) in our poet, an “indian princess” (75) at our sides “coasting down the hill listening to juicy” (74) in a kaleidoscopic return to an understanding of what it means to be a self, a star among many. The intimate hue of lewis’s confessional, in “mid-80’s neon glitz” (28), reaches out to you now, responsive reader: “this is who you are this is where you’re going here we are” (50).

Silence is tuning into static

In tuning into memory, “reordering the past,” lewis turns up her radio dial, having “fallen in love with the idea / of static” (73), and changes channels, entering the static — “i’m a radio” (45) — all to arrive at a meditation on silence. Throughout daryl hall is my boyfriend lewis creates exquisite (present) moments of reflection, as introduced on the first page of her collection:

not realistic but real

the fleeting pressures of

one creating silence [listening closely to the silence]

there’s nothing graceful about

always wanting. (1)

The busy bee mind is at work, disallowing a peace of mind in the present:

so there is no refuge in listening to your own silence

whenever you’re ready to head home and remain indoors “forever”

you still can’t. (1)

“trying to love myself” (30) becomes a lifelong destination, a long-term path of growth in which “you’re going to need all your happiness to grow up” (73). It’s inside the static-like “waves crashing” that the poet restores moments of self-contemplation. Self-love? In the poem, “some strings are better left undone*,” lewis reflects:

a lot of the time you can’t really tell

— like that static sound that sounds like the waves crashing

“i’m reaching the point where i’m wondering if that feeling is just life”

wanting things to be different than they really are

but we’re like aliens, a part of everything

and nothing at all. (43)

Tuning into the static of memory’s many siloes to arrive at self-observation, lewis unifies us in our alien-ness: we all are a part of “everything / and nothing at all.” A Zen-like state is enacted on the page through blank space, “white noise” (39), balancing energies between the poet’s sculpted lines. Quietude, that pathway to self-gnosis, recovering “[what might have been lost]” (9) in a “what we didn’t get then we get now” (38) triumph, serves as salve in the collection, comforting in the background on a field of “white sparks” (62), interrupting the “song” to embalm the poem:

the hinterlands of what we used to know

drums on the rooftop

[so] quiet, so awesome in the quietude

i can hear my heart beating

i can hear everyone’s heart. (76)

Time = “now is forever”

Perched on her “timeline of trees” (53), singing from a present perspective in which “now is forever” (19), lewis composes (engages) “whole stretches of time” (49) in a performance that renders “memory as current / perception not nostalgia” (53) and does so in a way that could make this a collection on the treatment of time travel. In “don’t you leave me sitting here in atlanta*,” a poem dedicated to Dan Thomas-Glass, who previously collaborated with lewis, the poet makes known her “plan to slow time, stash it in inescapable” (53). What does it mean to “slow time” and to “tend to our memories instead of the present” (54)? It means “to air the past” (74), to re-sort, to reorder. It means to go there by traveling through the mind. The poet emboldens in “i don’t need a reminder of the love that went away*”:

i’m writing to you from 1977

i’m writing to you from 1991

paper trails on a mountain

opening your lungs

and only you will understand why

to air the past

today is a day for someone else. (74)

Thoughts about time appear repeatedly metaphorized as origami, which holds the collection together in one powerful recurring image: “so the thinking was like origami / everyone folded neatly into [tiny/little] / birds” (1). The poet witnesses and, in “there’s so much more than promises*,” negates:

i want to love you in real life

but am mixed up with you in an anxiety way

a head full of paper shredded nothing like origami. (55)

The many folds of time are in forward motion within the collection:

“oh time, it’s leaving, i have to remember that”

just falls over itself, like origami

whiplash style. (14)

lewis pressure cooks time and lets her reader digest and absorb her results. In “i’m only joking but you better be right*,” time’s distortion is focused on — in a negative light:

you’re right

this is the end of something

here is the entire circular façade

i have no trumpet

distance distorts one’s sense of duration

time here doesn’t alter anything

where are you

i’m sitting in the grass

i’m at this place in my life

this is what holds the world together. (81–82)

The grandiosity of time, and “thinking about how large the galaxies are” (67), overwhelms. As readers of poetry, we often feel “like the most distant point” (66) outside the work, attempting to commune with the poet’s thoughts. And we are, in direct address, reminded of our “point” and proximity to vast thoughts, such as contemplating time and the universe and our position in it. lewis sums it up in the opening poem to the second section of the book, “instrumentation”:

the truth is

i remind you of smaller things/inform you of your smallness

and this is pouring this is pouring out [ /this is terror]

[it is very temporary]. (43)

Truth — or confess!

A preoccupation with the “truth,” what is “real,” what is “fake,” and the “series of lies” (34) we tell ourselves — “some memories you’ll make up to fill the gaps” (49) — permeates the poems. The poet demands in “you know i can’t imagine you were the magic*”:

tell me again who i am …

tell me anything as long as it’s true

you have wrecked me into my real shape. (64)

Shaped by her beehive confessional, the poet affirms “this is the truth / this is fiction / what happened what hurt this new game” (45); and “i need you more than anything else in the world*” maintains “we fake the sound / of living in lives lived messily” (76). The poet, who’s “not going to lie” (66) and who likes “people who are honest about their lives” (66), wonders if she’s fooling herself (65) and relates that “we’re not so / different in that we prefer being lied to” (64). Is memory then a trickster of the mind; “memory is [as] fiction” (10)? In “if you’re in it for love you ain’t gonna get too far*,” the poet laments that she wishes she had more interesting memories to share and likens them to “nostalgia or paralysis” (26). There is also the problem with “the act of remembering wrongly” (53). Since memory is subjective, who would question another’s with the assuredness of having an absolutely accurate and truthful one intact? After all, we are told that “the relation to the past has nothing to do with memory” (67). What may be the most authentic or “real” are the feelings — wound and wonder — circulating about the past, even though our “autopilot” (74) reveals, “i think i’m perpetually going to be in that wounded / faux-wounded position / the white noise the background music” (39). We feel them in our present “not by the accuracy of our memories but by our willingness to question / them” (38), honest in the fact that we are “no longer missing actual intimacies but imagined ones” (26). lewis questions in “we keep on missing each other*”: “or is it about interrogating what / something could be, or / might be, or is capable of becoming” (49)? “yes yes this is the true true,” the poet sings, “i don’t have real relationships with people” (54). Declaration or deliverance? What is “real” is “true” and what isn’t, is “just fake” (24) like “your fake name” (63). lewis ponders in “there’s so much more than promises*”:

i know you’re never going to understand

sometimes we are all here with the lights out

perpetually young

making bad fake decisions

we burst for need and thinking wrongly. (55)

We are constrained by the human condition, in our “disguises” (63), and with “blunt physical truths around us” (69), reworking and remaking our pasts in which “we all want to be the hero of our own story” (61). To narrate along the way is to be human. To tell our “stories” (our songs) — however made up or “fake” — is distinctly human. We need to relate, even if we “pretend that words can make a humanness between us” (43).

Humans, horses, stars: Otherness inside us

Whether it’s returning home to Ohio in fragmented conversations with a sick mother or returning to ’80s pop songs to discover oneself a grown adult, lewis masters the use of the collective “we” in a layered confessional to the self, exploring what it means to be “human” in a shared experience of our humanity. It doesn’t matter either if the memory isn’t “real”; as readers we sympathize with the poet’s intentions, growing up with family memories in “the ways and means are the parts subject to change*”:

these are the things that were beautiful in my life

my aunts told wonderful stories we had a very strong family my

mother’s sisters loved each other intensely the uncles loved each other

intensely those were

the days when it meant something. (38)

In “everytime you go away you take a piece of me with you*,” lewis revs up in philosophic mode:

i can only begin this once

if i possess only distances

we are the we we were not

i.e.

the problem with the past

the code we punch into our lives

understanding has everything to do with instability. (56)

Our inability to comprehend everything in our past is our shared humility. This admission and awareness is a key entry point into lewis’s collection; we discover how the mind is “running in circles / coming back as we are / objects of our imperfect human devotion / the sound of things we know” (70). And that we ought to “stop pretending / we’re ever going to make anything of ourselves / … it’s ones and zeroes, it’s not personal” (71), because “what we’re nostalgic for is an intensity / here, god” (37), i.e. to be present. Imparting a sense of oneness with her audience, the poet continues to relate in “i’m sorry i said i’m sorry*”:

we count ourselves

as having other people’s

refractory feelings

we never hold ourselves up

when you think of gravity [it is] this way

in haunting slow motion. (67)

We’re all included, for “everyone is a heartbreaker everybody is the one that got away / all you know is you need more / in this almost human refrain” (67). Later the song curves into a resigned bitterness: “because we don’t know anything / what became of / the fucking rain / the fucking snow / this long sense of human experience” (77). Another moment in which the poet synthesizes with her reader opens the poem “you must be thinking something but you ain’t saying nothing*”:

hearing my way into yr words, my own, these songs

and we are so many pieces

and this feels like us trying to

figure out the way to move on from it

not to abandon it but to keep it in its place and figure out what’s next. (15)

Empathy and human otherness found in ourselves is displayed markedly in “what’s this thing all about true blue*”:

you can’t be turning me on and off again

it’s hard not to notice

how you wear the feelings of one person modified by another

in the feelings of one person modified by another

i feel peculiar noticing this

the moment is important to me now though as something special to put

away. (24)

How our behavior of modifying others with our feelings is universal might need another collection to fully explore, but here in this one lewis beckons, “and what do you sing to one another when you’re still evolving” (52). We are also reminded that “you don’t accept your weaknesses the same way that you love / the weaknesses of others” (45) next to the fact that we all come from a mother, another body “outside” ourselves. The poet’s mother, in addition to aunts and the “father curiously absent” (82), makes regular appearances throughout. Early in the collection we learn that “my mother used to / say a penny for your thoughts” (5) and by the end of the collection the poet feels that “maybe mothers should know the ends of the stories they tell” (73). In the collection’s final poem, “the silver leaves the drones of clever talk*,” the return home to mother is reflected upon in “conversations again / artifact by artifact”:

i remember now

i am my mother’s age

doin my best patti smith. (85)

The collection then might be called a return to origins — back to the womb — to a “real” self; lewis assures “we will become ourselves” (3). While “mother” is a familiar motif that surfaces as a returning source (home) in the collection, another powerful image riding alongside her is the horse. If each poetry collection can have its own “spirit animal” (lewis suggests) then the wild horse is a good choice for daryl hall is my boyfriend. In the collection’s final section, “rarities and b sides,” horses mesmerize in several poems. In “i’m just looking at you through crazy eyes*,” we are likened to horses:

the way we look like horses

chewing through the narrative

smashing face-first into the mortality

in the old sense of awe

standing over the expanses. (77)

The unassuming and unattached intuition of horses is revered in “have i been away too long*”:

horses always know something

they don’t want to love you

they just want to hold you

that slow motion vibe

we have the same truth. (79)

Other poems follow in the collection noting that “it is the year of dark horses” (81), and in “words of comfort too*” the need is “to seize those wild horses / and ride them / the needs those scatter lines we took / home after the new year’s eve party / it’s weird to see your life in other people” (84). We arrive at the end of the book in the “year of the horse” (85), when “your mouth looked [so] cool in the light / a choir of echoes” (85).

Above the horses are “stars,” and they are sprinkled all over the pages of the collection. There are far too many to cite them all (as in a starlit sky), and by the end of the book we’re feeling like stars ourselves, having sung along with the poems and having recognized that we too are a “distant point” (66) in the universe. Our autopilot poet remarks “[the shift of stars without feeling them fade]” (15). We learn that “slits are stars” (9), then once again that“stars are slits” (61), and that it’s possible to “cut and paste the stars across your face” (61). In the poem “there ain’t no right or wrong way just a play from the heart*,” we discover that “statistics tell us we’ll see the stars again” (11), and sometimes literal stars become conflated with pop-rock stars. In “people have a tragic habit of letting love get in the way*,” lewis writes:

“my heart is beating in a different way”

and now i’m your favorite star

distancing in one long movement

working backwards piecing together the scraps

i want to get so close it blurs. (51)

We’re left perplexed in the complex cosmology of the poet’s serial song. Meandering through lyric, refracting our light and being refracted (modified by others’ feelings) by our own light, we mix with the poet’s light until we’re riding our “own altitude,” feeling “like the most distant point / all lit up” (66).

Form/process

Most of the poems in daryl hall is my boyfriend move down the page in an open form lyric, enacting memory’s many fragmented streams, complete with spatial gaps (silences) as witnessed in “i can’t go for just repeating the same old lines*”:

— or that feeling is

a prompt to return

a laugh to shake the dreams out of my head

(girl’s name) and (boy’s name) sitting in a tree

[still an essence in the other’s memory]. (22)

No capitalization and very little punctuation are employed; the use of quotes (where noted as interviews, appropriated text, or conversations) and slashes and brackets pepper lewis’s poems. The free form movement of the poems allows the reader to enter the songs — feeling at times right in the middle of them — and feel tuned in. The forward slash both moves forward in time and stops (in beat with time) acting as an aesthetic placeholder on the page — visually creating a pause in the poet’s breath/meter. Brackets also feel like inner whispers — more than asides — and are intrinsic parts of the poems’ structures vibrating their own energy (voice). Toward the end of “you must be thinking something but you ain’t saying nothing*,” the poet shares her process (“constraints”) directly. Here, process, content, and form (the use of “/” and “[ ]”) all synchronize to come into play:

dear abstraction inherent in these constraints, i want to document

the inaccessible and uncomfortable to hold/ the little fictions

we tell ourselves

[that suitcase of something with something inside

recorded from far away]. (15)

Willingness to offer up one’s writing process, embedded within the work, is helpful for readers, and lewis does so in her collection, letting on that she’s “switching my ideas into a pop format” (34) — that is, song. She also notes how being in love with everyone she grew up with has “helped [her] think about seriality and transition” (66). Is love inside the body, trying to come out through song, or is it outside ourselves, “like two different songs” (9), trying to come in? Maybe it’s a little of both, magnetism? Witness, confessor, singer, the poet — who realizes “god, i should sing” (19) — takes song and spins it on its toes, imploding her past to reload her present in finely crafted lines with occasional breakouts of repetition: “and the north / and the north” (82), “and sing my love / and sing my love” (69), “enough to weep over it / enough to weep over it” (78), “turn it into magic magic” (73), and “make it rain / make it rain” (79). Repetition rocks us gently into the field of song, affirming that these poems need to be read aloud.

In her generous note at the end of the collection, the reader is treated to a postscript, which lists other artists (aside from Hall & Oates) who have helped instigate (“trigger”) collaboration with the poet through use of their appropriated texts. We hear Lionel Richie’s “Hello” and find Jean Genet, LeRoi Jones, Melissa Eleftherion Carr, and lines from various Pitchfork interviews (mostly Ryan Dombal’s) collaged into the poems. Conversations with the poet’s ill mother “up to my arms in the cancer” (73) haunt the work, especially in the collection’s final poem, where close readers feel the arrival home to Mother, who opens the last poem with “you look like one of those moon girls” (85). We are left in wonder to wonder.

The project: trilogy

daryl hall is my boyfriend is the first of a box set trilogy promising further continuity and sequence. The cover artwork (by Mark Stephen Finein), in pink-crimson neon ITC Serif Gothic, gives the appearance of a handwritten journal, whose title (feeling sure of itself) looks like it may have been scrawled by a teenager during Hall & Oates’s prime, wearing an “80’s reference point” (83) in a kind of Miami Vice-skin. lewis’s attention to process allows even the poem titles, when read together, to read like a complete poem. On the contents page for the section “rarities and b sides,” several song lyric titles, when read back-to-back, transform into an individual stanza of loss:

day to day, to day… today 61

the dreams you want to be either stay or get away 63

you know i can’t imagine you were the magic 64

all the days i’ve lost hoping and pretending 65

maybe we’ve been alone too long 66

i’m sorry i said i’m sorry 67

Memory is a wondrous connective tissue, and lewis succeeds in stirring ours through her own, offering her reader a shared intimate experience in the lyric of You and I. And our poet, seasoned by time that enfolds like origami, knows that song is the vehicle to enable such a lyrical relationship. Using these Hall & Oates songs, these poems manifest as memory’s modified appliqué to rouse the feet that once danced to them, leading us to the poet’s confessional, where she reproduces herself “endlessly in these lines / suture identity to memory / scar to art” (26). She is “not going to lie” (66) and knows she’s (we’re) dealing with old wounds that only an “old version of the song” (45) might remedy — and “you me us them” (61), we’re all in it, drenched. In a versified memoir to the self, in “re-ordering the past,” how much does it matter whether how we remember is the correct way, that our stories (our songs) are “real,” “fantasy,” or “fake,” or whether our “true” home is in Ohio or here or there? What is recalled and what is appropriated is marked by time and distance. lewis, who knows the awesome space (and terror) that silence brings, awakens our smallness and lights it up, making us “stars” in the game of resinging, resigning, and reassigning memory. The poet’s epic is our epic, since “we all want to be the hero of our own story” (61). At the end of daryl hall is my boyfriend, I felt a little more aware of my wounds (my own humanity) and refreshed by the healing property that writing and reading can bring. Home in the awareness of “how life shapes and re-shapes us” (32), I trust that the “songs outside of people” (29) are also within me awaiting their trigger; and I’ll be on the dance floor with them (mid-’80s style) till lewis releases her forthcoming follow-up collection, mary wants to be a superwoman.