Performing crip/queer survival

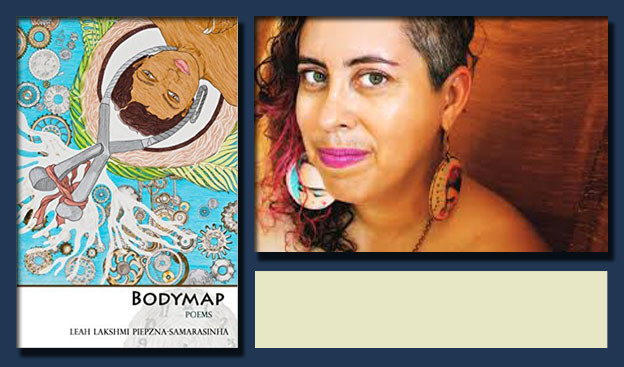

Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha's 'Bodymap'

Bodymap

Bodymap

Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s new book of poetry, Bodymap, insists we understand technology as “the practical application of knowledge.” This makes it possible for us to view survival as a set of skills and aesthetics, not as an end. Bodymap is a performance and a text, a love song to and an archive of working-class femme-of-color disabled experiences. Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha uses her hybrid poetic form and structure to center assistance and interdependency as a site of politicized cultural knowledge production, equipping oppressed individuals and communities with a multiplicity of generative “methods.” These methods are “the psychic and communal practices that arise at the margins of a marginalized community,” which exist simultaneously outside of, and within, oppressive systems.[1] These individual and communal survival technologies are what produce oppositional consciousness, praxis, and aesthetics.

In order to politicize these communities and their affective labors, Borderlands Performance Studies scholar Chela Sandoval unites these skills under a framework she calls “methodology of the oppressed.” At its core, this social circuit of survival technologies is the practice and performance of knowing the conditions of the present. These differential forms of “oppositional consciousness” are the various areas of expertise, skill sets, patterns, and knowledge productions that occur under the conditions and positions of a marginalized existence. Using this framework, artistic forms and aesthetics emerging from the borders of the oppressive hierarchies of power and control become, “an effective means of individual and collective liberation.”[2] In their book, Performing the US Latina and Latino Borderlands, Sandoval, Arturo J. Aldama, and Peter García identify these methodologies as “decolonizing performatics/antics.”[3] Designating performance as the practice of decolonial intervention provides the groundwork for establishing an affective affinity across experiences, embodiments, and theoretical disciplines. Therefore, the various processes of resituating form and meaning by “reversing, releasing, and altering an established coloniality of power” become “the components of an aesthetics of liberation.”[4] By reclaiming “prophetic love,” or “oppositional social action as a mode of ‘love’ in the postmodern world,” Sandoval politicizes the differential affect linking folks who are impacted by the consequences of oppression.[5] This linkage encourages us to think critically about the powers of cultural production through a decolonizing lens.

With differential affective survival methodologies at the heart of this movement, performance becomes an effective site of resistance. Part of this resistance is performing the struggles and strategies utilized for building support and trust within and between communities. Within the framework of Methodology of the Oppressed, performance privileges aesthetic productions based on differential embodiments, knowledges, survivorhoods, and affects. However, decolonizing performatics/antics are not confined to the stage; Bodymap’s concurrent performative, archival, and activist impulses effectively position oppositional consciousness as a political site of decolonizing knowledge production. Because of the ways Bodymap insists on performing a crip aesthetics rooted in alternative methods of relationality, assistance, pleasure, and pain as “a set of technologies for decolonizing the social imagination,”[6] Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s focus on disability theory and praxis aligns with Sandoval’s Methodology of the Oppressed to expand the developing field of intercultural performance methodologies.

According to the editors of Performing the US Latino and Latina Borderlands, “decolonial performatic/antic” methods often centralize artistic techniques such as “parodic-pastiche, hybrid, [and] bricolage aesthetics for generating myriad possibilities for expression.”[7] The structure of Bodymap itself performs a crip aesthetics by utilizing a multiplicity of poetic forms as a decolonial intervention. In fact, Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha carefully endeavors to fail at embodying these various forms. The pages are comprised of love odes to cars and discount stores, lists logging imperfect and painful sex moments, “non haikus,” and unexplained abbreviations. Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s “imperfect” or “unsuccessful” use of form manifests the differential affective experiences of being a working-class disabled queer of color. Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha often uses enjambment at the end of stanzas to express an abrupt change in time and geographic location. In the poem “sternum,” Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha connects the two stanzas by a tattoo, not by linear time:

said home? home is right here

and touched her chest light

a year later

when you drilled the needle into my chest

and tattooed home there (97)

Here, the unpunctuated passage of time is meant to express the diasporic affect of being a working-class disabled queer of color. Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s rearticulation of poetic form to represent the oppositional consciousness of having to manage multiple homes, identities, and institutions for survival functions as a decolonizing performatic/antic.

In fact, Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s emphasis on “home” throughout the book signals her insistence on mapping differential crip cultural productions. There are many moments where Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha intentionally names crip and queer spaces and assistive technologies.

Leave us crumpled in sweatpants on our beds, vibrators always plugged in for pain control, herbal infusion in big mason jars, cell phone where we text our friends when we’re too gone to call, on hold for the low-income queer clinic for sliding-scale acupuncture, again. (39)

By exposing the ways in which working-class disabled queers of color make systems that are not designed to keep them alive work for them, Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha cites crip aesthetic production as a source of resistance to ableist, hegemonic power and control. By documenting everyday moments of surviving the experience of being sick, tired, and in pain, Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha unites a community across difference through a common love for the places and things that keep them alive, and therefore the desire to resist the oppressive systems that make those technologies inaccessible.

By boldly professing her love for the people, spaces, processes, and technologies cultivating, and assisting, her community, Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha contributes to a collective working-class disabled queer-of-color blueprint.[8] However, Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha is not mapping single spaces or objects; she is pinpointing the various ways in which people are assisted by, or assist each other with, these technologies:

She fucks my pussy that’s so tight after six months of nothing, says, you are so tight little girl, open up for me, that’s right — and I don’t have to work to come. And I cry when I do cause it’s like all the pain, all the not-enough, all the worked-to-death worn-through tired crip body, is coming out of my pussy onto her hands when she gives me what I have needed for so long.

Later, she texts me, “I could tell you needed to be fucked so bad and I was so happy to be able to give that to you.”

And then there was the moment on Skype where she said, “Only the hottest girls have fibromyalgia” and I threw back my head and laughed and laughed and fell in love. (64–65)

Here, Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha insists on the indispensability of sex and technology as assistive, healing methods of survival. As she recalls this crip sex moment, the present tense and the long lines convey an intense sense of urgency. By framing interdependence and relationality as both a fleeting pleasure and a life force, Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha transforms this methodology into a technology, and in turn, a source of knowledge production. Bodymap is mapping the differential, oppositional modes of interdependency keeping her, and her community, alive. This way, acts of interrelationality and assistance are positioned as an essential component of decolonizing resistance.

While Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha is intentionally documenting this specific encounter, its poetic, performatic quality still preserves the moment’s transience. Using poetics as a method for compiling a blueprint, or an archive, of working-class disabled queer-of-color experience, she centers partiality as an essential feature of crip queer aesthetics.

Recognizing the partiality of Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s work as an essential feature of a working-class crip queer-of-color aesthetics not only shifts the readers’ expectations of what technology is, but also challenges our ideas of what an archive should look like, or work like. What qualifies as a documentable “trace,” and what exactly does a map look like? To Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha, this is a map aimed towards documenting shared experiences of survival, and these experiences do not always leave a trace, or want to leave a trace. While Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha is compelled to document or blueprint a multiplicity of survival technologies to claim and decolonize aesthetic production, her archival impulse still assumes a partial quality in order to echo the precarious realities experienced by working-class disabled queers of color. The signposts present in Bodymap’s “map” are often coded, like an informal conversation between friends. The majority of Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s poetics are written using a kind of lingo specific to working-class disabled communities of color. Therefore, Bodymap offers assistance and communality to those who understand it, and requires translational work from those who do not.

the slow/walking lane of the Berkeley Y

you on the wheelchair lift, me walking slow, slow

all of us on our low-income memberships.

The elevator of every BART station,

any elevator, anywhere

any ramp, any time

any house where we bed bound jail break time

the community acupuncture clinic waiting room

my friend’s living room

where she exquisitely tops her PCA about precisely which dish to use

and gifts me with the ability to lift her palm. (55)

The idioms, abbreviations, and unexplained locales mentioned in the poems are the necessary codes Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha and her communities have learned while “negotiating a landscape of inequality.”[9] In doing this, Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha portrays the fleeting, and oftentimes unstable, methods of survival a poor disabled queer of color may experience. She also preserves her community’s privacy, especially of those who receive “illegal” or “unconventional” medical assistance. Except, by exposing these survival technologies through performatics, Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha also legitimizes the occurrence of such events and therefore politicizes their existence.

While Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s own performatics politicize her, and her community’s oppositional modes of being, thinking, surviving, and documenting, the book lays the groundwork for future reimaginings of what oppositional social action as a mode of love should look like. By blueprinting the methodologies of a crip queer existence, Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s “differential” poetics opens up more possibilities within the framework of Methology of the Oppressed, ones that push creativity beyond the materiality of survival. Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s representations of non-normative movement, cripness, and especially crip queer sex moments, are a part of a larger project seeking to map future social relations. Performance-studies scholar Jose Muñoz argues, “queerness is also a performative because it is not simply a being but a doing for and toward the future. Queerness is essentially about the rejection of a here and now and an insistence on potentiality or concrete possibility for another world.”[10] Muñoz’s work clearly resonates with Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s contribution to decolonial love as resistance. Her various assistive relationships with her lovers, her friends, herself, and even with the various oppressive systems she must manipulate, are all oppositional, yet practical and hopeful applications of knowledge. By centering technology as crip aesthetics, and crip aesthetics as technology, Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha qualifies assistive, cathartic, and healing modes of being as intrinsically political. She does this in her writing, and by making the book itself into a kind of oppositional love anyone can perform, memorize, or use in a critical analysis. Bodymap is a text, a performance, and an archive, an assistive technology and a decolonizing performatic dreaming of oppositional affinities, interdependencies, and sledgehammers to inaccessible curbs.[11]

1. Arturo J. Aldama, Chela Sandoval, and Peter J. García, Performing the US Latina and Latino Borderlands (Indiana University Press, 2012).

2. Chela Sandoval, Methodology of The Oppressed: Theory Out of Bounds (University of Minnesota Press, 2000), 3.

3. Arturo J. Aldama et al., Performing the US, 6.

5. Chela Sandoval, Methodology of The Oppressed, 146.

7. Arturo J. Aldama et al., Performing the US, 2.

8. The grief experienced by queer communities is a pivotal source for the politicization of queer existences and is what mobilizes folks to build, maintain, and theorize assistive queer spaces across difference. Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha makes a reference to Amber Dawn’s “Where the Words End and My Body Begins,” in which queer grief is reimagined as a “blueprint.” By quoting Dawn, Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha is simultaneously contributing to and professing her love for the act of mapping queer/crip spaces and figures. See Amber Dawn, Where the Words End and My Body Begins (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2015).

9. Arturo J. Aldama et al., Performing the US, 262.

10. José Esteban Muñoz, Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity (NYU Press, 2009), 1.

11. A reference to Robert McRuer’s “Coming Out Crip: Malibu is Burning,” in Crip Theory: Cultural Signs of Queerness and Disability (NYU Press, 2006). Citing McRuer, who is an extremely influential crip/queer scholar (as well as José Muñoz) is my way of building on Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha’s crip/queer cartographic efforts. In the spirit of the crip-queer blueprint, I cite McRuer and Muñoz as a way of “professing love” for their work and thus, contributing to the crip/queer mapping process.