Living Dada

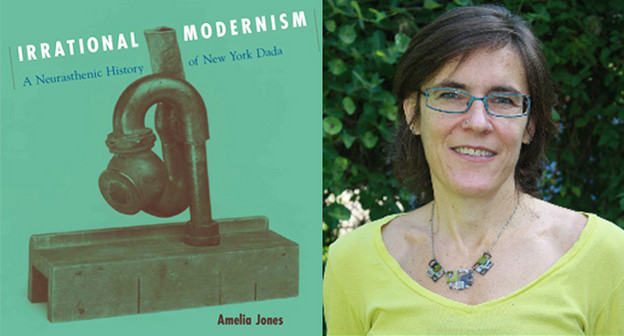

A review of 'Irrational Modernism: A Neurasthenic History of New York Dada'

Irrational Modernism: A Neurasthenic History of New York Dada

Irrational Modernism: A Neurasthenic History of New York Dada

“Why should I — proud engineer — be ashamed of my machinery?”

In her poem “The Modest Woman,” published in the modernist literary magazine The Little Review in 1920, the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven derides the prude and celebrates the female body and modern form. A German immigrant, artist, and poet, the Baroness was a vibrantly disruptive figure in New York City’s avant-garde. A living, breathing vehicle of avant-gardism — since called the Village’s Tristan Tzara — she embodied the spirit and aesthetic of Dada. Parading through the streets in outrageous found-object costumes — tomato-can brassiere, postage-stamp beauty mark, spoon-and-feather hat, with her giant penis sculpture in hand — she constructed her poetry, sculpture, and self from the detritus of the modern city. American art historian Amelia Jones observes that the Baroness wore “modernity and its violent effects in and as her body” (29). The aggressive fervor with which the Baroness lived and created her work unsettled even the avant-garde and is the driving force of Jones’s Irrational Modernisms: A Neurasthenic History of New York Dada, an art historical book on this early-twentieth-century avant-garde.[1]

So when poet Eileen Myles enters a conversation about conceptual art and subjectivity in her May 2013 essay “Painted Clear, Painted Black,”[2] she pulls on the threads of a conversation long under way. She enters by way of a comment made by Marjorie Perloff about her writing: that it is an example of “transparency or feigned transparency” in poetry. Myles deliberates on the meaning of “transparency,” and why it seems to be an objectionable thing. She wonders: is the rejection of an embodied subject behind the work a rejection of conflating author and art, of the lyric speaker, of an authentic self?

Myles also wonders if the call for an end of transparency is actually code for discomfort with identity politics, the feminine, the speech or bodies of women, queers, or people of color. In making the case that subjectivity and conceptualism are not incompatible, Myles reminds us that postmodern play is not necessarily at odds with the feeling (of) bodies of artists and audiences, and that subjectivity need not be simple or singular; nor is all conceptualist art disembodied. She understands the avant-garde to be “composed of a shaky grid holding a multiple of approaches” and notes in the “theory world outside of poetry, feeling is hot stuff.” I would add that not only has “feeling” been hot stuff in critical theory and literary studies for decades (what’s been called the “affective turn” happened around 2000), but visual and performance arts have a long history of interest in the body, feelings, and questions about reception. Myles identifies contemporary poets doing “unabashedly postmodern work that is free wheeling and exacting in its deployment of emotion” and reminds us that sound poetry is a bodily performance and that appropriation has served to mourn or mark a moment. Troubled by the misogyny in a conceptual writing process in which “womanly transparent feelings are now successfully marshaled into order,” Myles reminds us that in art there is feeling — “Feeling is an inside and outside gong. It’s history.”

I begin this review with Myles’s piece because I am struck by how much it resonates with Jones’s 2005 interdisciplinary art historical book, which revisits the early-twentieth-century New York City avant-garde by way of the recently rediscovered Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, whose biography and art illuminate this history of feelings and bodies working with and against cultural forces and aesthetic constraints. Because the life, body, and art of the Baroness were one and the same. Strangely and spectacularly ornamented and overflowing with what she scavenged from her street wanderings, she might, in the words of Jones, “help us understand how the messy, personal, and subjective have — in waves, beginning at least with the rise of identity politics in art world discourse in the late 1960s — begun to reemerge with increasing force to challenge the repressive boundaries of the restrictive patrilineal model of art practice and art history” (27). In Jones’s compelling alternative history of New York Dada, the Baroness is not simply an overlooked colorful character; nor is she a marginalized artist to be inserted into a preexisting narrative. She influenced avant-garde culture, inspiring, enacting, and creating innovative Dadaist art. Documenting her sharp wit and the sensual pleasure she took in interacting with the materials of her world, her exciting body of work includes and combines assemblage sculpture, sound poetry, visual poetry, painting, diagrams, fashion, and performance. As Dada embodied, the Baroness is a form of what Jones calls irrational modernism, and as such is representative of a new approach to understanding the historical avant-garde, one that “revises our current conception of radical artistic practice” (24).

In 1922, Jane Heap and Margaret Anderson, editors of the American literary magazine The Little Review, saw the Baroness as representative of American Dada and featured her in their modernist magazine — along with Mina Loy — as the face of Dada, declaring her “the first American dada”: “she is the only one living anywhere who dresses dada, loves dada, lives dada” (5). When one encountered the Baroness, one came into contact with a disorienting mélange of seemingly incongruous landscapes and materials: she was known to carry around canaries in a cage; wear gilded carrots and beets, a readymade shovel earring, and a gold curtain tassel belt; and model outfits she made out of maritime flags and machine parts. She subverts what Jones identifies as the dominant model of avant-gardism, one that “is predicated on the erasure of the subjectivity of the artist — the messy and potentially compromising aspects of her or his sexuality and other biographical vicissitudes — from the artistic encounter” (21).

For Jones, the Baroness, “in her inimitably fluid and destabilizing way, thread[s] her way through the book, just as she insinuated herself into the circles of artists and writers now associated with New York’s World War I-era artistic avant-gardes” (10). Her itinerant movements and art-play in the city brought her into contact with its avant-gardists, with whom she had both accord and discord. She collaborated with them and critiqued their art, including that of her good friend Marcel Duchamp, with whom she shared an affinity for found-object art assemblages and plumbing sculpture. (Who first had this found-object affinity is a question that Jones takes up; following the lead of Baroness biographers, she suggests Duchamp’s Fountain came from the Baroness.) Given her involvement in and contributions to the American Dada aesthetic, the dearth of attention given her in modernism’s histories is shocking and dismaying. Jones takes the Baroness seriously, intricately reweaving her back into place in New York City’s early avant-garde; her presence provides new and different lenses with which to see and understand these artists and their art. In this role, she is a productive irritant for Jones, who seeks to examine and highlight what she calls artistic subjectivity: “by attending to the lived avant-gardism of the Baroness, I want to revise our current understanding of New York Dada as a group of visual objects and images whose meaning and political significance has remained more or less static over time and, thus, interrogate our understanding of avant-gardism and even of art history and modernism themselves” (13).

The Baroness’s “lived avant-gardism” inspires the richly textured art-historical narrative of Irrational Modernism, which details the cultural and social dynamics of New York City avant-gardists as they worked, wrangled, and collaborated with one another before and during World War I. Jones highlights correspondences between the lives and art of the Dadaists and the dislocations that modernity and the war had set in motion: specifically, how the war, immigration, Fordism, Taylorism, and the city’s shocks of modernity were reconfiguring borders, bodies, and psyches, as well as shoring up social and gender norms. Of particular interest to this book is the impact these unsettling forces had on Marcel Duchamp, Frances Picabia, Man Ray, and the Baroness. The Baroness was unique to the group in that she “enacted the violent dislocations in personal and national identity put into play in the period” (36). As Jones explains: “the Baroness is a figure whose boundary-breaking performances rearticulated gendered and national identity to an extent far beyond that to which most of the male avant-gardists, their anti-bourgeois proclamations aside, were ever willing to go” (36). Thrown in jail many times — for wearing a man’s suit, stealing an umbrella, assaulting poet William Carlos Williams, being suspected as a German spy — the foreign, androgynous, sexually aggressive Baroness failed to fit into even the avant-garde’s categories, “flowing threateningly forth across the boundaries of respectable avant-garde behavior” (10).

It is the queer figure of the Baroness, threatening in her challenge to gender identity and to norms of social behavior, who enables Jones to write what she sees as a needed alternative view of New York Dada, one which the Baroness facilitates by “reenacting the very irrational effects that she so dramatically stood for at the time, performing the seedy and seamy underside of modernism that discourses of high art and architecture have labored to contain through their dominant models of rational practices” (10). For Jones, the Baroness offers an alternative way of negotiating the “mad rationality” of industrialism. In her flâneurial immersion in the spaces of urban industrialism — as “an androgynous German woman with a voracious sexual appetite, dressed in urban detritus like a mentally ill ‘bag lady’” (9) —she enacts what Jones sees as a radical art practice. Unlike the Dada men, whose work Jones argues never fully embraces irrationality, the Baroness does not sublimate or repress the body’s response to the shocks of modernity. Instead, she revels in the modern city, appropriating and fabricating shape-shifting identities and transgressive art forms in and through a disordering of its language and objects. As an embodied sign of what is grotesque and carnivalesque in the modern city, she points to irrationality and incoherence as a way of negotiating its machinelike forms and forces. The Baroness exhibits the nervous condition of neurasthenia, a “complex network of bodily/psychic symptoms that rupture the subject’s smooth functioning” (28). Thus, for Jones, the Baroness and her “mad” form of Dadaism serve as a critique of modernity’s forces that work to regulate, control, and contain the body; she resists and confounds the discourses of rationalism, nationalism, and masculinity that occupied her time and place.

Jones offers a book about “doing art history,” what she labels an “overtly neurasthenic art history — disorderly, irrational, and highly self-invested” (28). In the first chapter, “The Baroness and Neurasthenic Art History,” Jones explains the role of the Baroness in this history by plunging into all of the book’s key concerns and concepts — neurasthenia, rational modernism, rational postmodernism, irrational modernism, readymades, and the avant-garde. Given the enormous ground Jones wants to cover, her narrative is quite dense, and at times disorienting, as she utilizes myriad lenses to examine and illuminate this group — psychoanalytic, historical, biographical, formalist and feminist — combining these approaches and sometimes switching gears abruptly. While this approach makes some sense, given the multifaceted nature of this project, at times it feels like too much too fast. Jones wants to do justice to her subject matter, and thus she comes at it from every angle, attempting in one book to take all possible paths of inquiry — now that the Baroness is on the scene.

Leaving Germany in 1913, Elsa Plotz arrived in America the year of New York’s revolutionary Armory Show. She brought with her the aesthetic and cultural sensibilities of the avant-garde communities of Berlin and Munich, where she had been living and circulating since the age of nineteen, when she left a difficult middle-class family situation — an abusive father and what she described as a stepmother’s “bourgeois harness of respectability” (7). In these cities, Elsa worked as a chorus girl, model, actress, and artist, and had a number of lovers and a couple of husbands. Not too long after her arrival in America at the age of thirty-nine, she married a disinherited German Baron — acquiring a title but no wealth — and shortly after their marriage, he went to war and died. It was in New York City that she began making, writing, and wearing her art. Embraced by some and scorned by others in its art and literary circles, Elsa in many ways remained an outsider: she was a German woman (arrested and imprisoned during the war), androgynous, and uninhibited about her sexual desires. Her art was mostly ephemeral, public, so not easily incorporated and placed in a exhibit, museum or institution. As a poor peripatetic flâneuse, she wandered the city streets, sometimes wearing a car taillight bustle, so as to, in her words, not “collide with anyone.” Yet, given her electric energy, she had collisions — with the bourgeois of the modern city and with some of the more buttoned-up modernists, including William Carlos Williams, who, as the story goes, first found her intriguing and pursued her, then felt such trepidation about her aggressive ardor for him that he took up boxing lessons to defend himself against her amorous assaults — calling her “a dirty old bitch.”

The Baroness challenged the period’s gendered and national discourses more radically and more overtly, Jones argues, than did the avant-garde men in the face of their fraught relationships with the war. Jones begins her history of the New York Dada with the impact of the war on “the best-known representative of the visual arts component of the New York Dada movement, the triumvirate Man Ray, Duchamp, and Picabia” (30), focusing on their distance from the war and their lives in America. She frames the second chapter, “War/Equivocal Masculinities,” with a quote from Freud’s “Thoughts on War and Death” (1915) about the “noncombatant individual” whose response to the disorientation of being a “wheel in the gigantic machinery of war” is an inhibition of “his powers and activities” (34). This is followed by a quote from a letter to The Little Review (1920): “The Baroness … [claws] aside the veils and rush[es] forth howling, vomiting and leaping nakedly … It is a blessing to come upon an unconscious volcano now and again” (34). If the Baroness unreservedly erupts and spews forth feelings about modernity in the form of bodily fluids, as noncombatant men in a modern city far from the war in Europe, Man Ray, Duchamp, and Picabia respond differently. In close formal analysis of their art, Jones sees anxieties about masculinity at play in the abstraction and destruction of the body, dysfunctional machines, voids, and “obsessive heroic enactments of male power” (133). Their work illustrates what she calls the “mad rationality” of modernity: feeling is sublimated and the body is broken, alienated, and dismembered, appearing as fleshless machines, glass, diagrams, and shadows.

In contrast, the lived art practices of the Baroness elude modernity’s appropriative logic, which would contain and rationalize that which is excessive, confusing, and other. The Baroness’s strange outfits, found objects, and readymade poetry cull the materials of her everyday, reveling in ecstatic and confused fleshy combinations of body, city, and world. Irrational Modernism might have spent more time on the Baroness’s radically innovative writing, which she herself called “readymades in poetry,” but as an art historian Jones focuses on the Baroness’s found-plumbing sculpture and assembled objects to make the case that her work serves as an explicit challenge to modernity’s oppressive forces of rationalism. Jones does not paint her as a complete anomaly of the time, however; nor does she set up a strict male/female artist dichotomy. She pairs her with the also historically marginalized Arthur Craven, who like the Baroness embodied the spirit of Dada in absurd costumes and performative bodily play that undermined the period’s militaristic mechanical masculinity. Jones notes Craven “lived his life and practiced his art (the two processes being identical in this case) in such a manner as to embody the male subject of urban modernity during the early twentieth century” (173). What seems most compelling and convincing — both to Jones and to me — is the way in which the Baroness’s body “became a kind of ‘readymade in action,’” an embodied “sign of the ruptures in the social (and gender) fabric during this highly charged period — of the uncontainable, violent, feminizing, debased, and debasing effects of modernity” (9). Jones turns to Chaplain’s broken feeding machine in the film Modern Times as a related image in her second chapter, “Dysfunctional Machines/Dysfunctional Subjects,” in which she investigates and rethinks works of the Dada canon with attention to the Dadaist men’s “feminized and broken machines” alongside discussion of the Baroness’s art objects and her writing on machine culture.

While the Baroness was terrorizing Williams, she was inspiring her friend Duchamp. Not only was she a living readymade, her art — much like his — appropriated material from the modern world: its streets, signs, stores, and newspapers. (In a painter’s studio on Broadway, the Baroness once recited her poem, “Marcel, Marcel, I love you like Hell, Marcel,” as she rubbed down her naked body with a copy of his Nude Descending the Staircase.) In focusing on her sculpture, Jones puts forth a proposition made by the Baroness’s biographer, Irene Gammel, that she very well might have given the famous Fountain (1917) to Duchamp to submit to the Armory Show. Not only does he mention in a letter that it was given to him by one of his women friends; it fit into her oeuvre of found-object sculptures, which explicitly cite female body holes and phallic parts. Her sculpture God, from the same year, is an iron plumbing tube mounted atop a wood miter box. Jones points out their shared appreciation for readymades that reference the fraught dynamics of man and machine, and of the body and industrial capitalism; Jones also deliberates on the Baroness’s art as excessive and playful critique in contrast to Duchamp’s art, in which the body is trace or an absence. Jones argues that “by circling around, rather than enacting, the compromised bodies of modernity, Duchamp kept his practice radical to a degree — but safe (and fully disembodied) [and] ultimately retained control and thus artistic mastery by choosing, contextualizing, and directing the display of each readymade” (141). In discussing the lives of Duchamp, Man Ray, and Picabia, Jones exposes what she sees as personal, psychological, and aesthetic negotiations of masculinity in response to the war. She is overt about her intention to provide more complex and more contradictory narratives than art history narratives in which these men are reduced to radical or genius artists heroically battling forces of industrial capitalism and normative masculinity.

Breaking down what she characterizes as the formalized rationalized logic of art history, Jones makes explicit her own personal interest in the Baroness and neurasthenia. Of her fourth chapter, “The City/Wandering, Neurasthenic Subjects,” she writes, “I increasingly overtly identify with — and project onto — the Baroness as a radical urban wanderer performing a fragmented narrative that itself is flâneurial,” and she characterizes art history as neurasthenic and as a mode of historical wandering (32). She is an art historian who has experienced neurasthenia in the form of a panic disorder, she admits, relating her emotional excesses to the excesses of the Baroness.

In the middle of this chapter, Jones includes a creative piece of writing in which she assumes the voice of the wandering Baroness. While this journal entry fails to capture what is formally innovative about the Baroness’s own language and poetics, it conveys the presence of the storyteller, conflating author and subject, which is clearly Jones’s intent. In the opening chapter, she states, “Anxiety is my mode of being. Sometimes reading about Francis Picabia or the Baroness, […] I feel attached to them by a hot, electrified wire of neurosis across the decades” (28). In these instances, and throughout Irrational Modernism, Jones is deliberate about her desire to dispense with the illusion of objectivity or neutrality in writing; she makes transparent her personal identification with the Baroness as a way of acknowledging the body and feelings of the/a writer in what is a sound scholarly examination of New York Dada. This is her boundary-crossing, a intervention of feeling in staid institutional art historical writing. While I imagine some readers might feel uncomfortable with this — which might be the point — I appreciate her intent. In making explicit her interest in the Baroness, Jones calls attention to what compels her writing, her art-history-making — and to how one feels her way into and is present in art.

Irrational Modernism is a compelling contribution to the recent (and belated) attention to the Baroness and her radical form of lived avant-gardism,[3] one in which she “performed a kind of unhinged subjectivity that most of the other artists of her day only examined or illustrated in their work and that many, in spite of their aspirations to thwart bourgeois norms and define themselves as avant-garde, assiduously avoided” (5). In her avant-garde community, the Baroness “shone a raking light on the limits of radical practice, galvanizing debates” that dismissed her as “beyond the pale of avant-gardism” (209). This same raking light illuminates our current debates about avant-gardism and feeling, given that the exciting body of the Baroness, her felt and feeling art, anticipated and informed future avant-gardes, performance art, feminist and queer art, and conceptualism. In her poem “Constitution,” the Baroness “Still / Shape distinct — / Resist / I / Automatonguts / Rotating Appetite — / Upbear against / Insensate systems.”[4]

1. Amelia Jones, Irrational Modernism: A Neurasthenic History of New York Dada (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2005).

2. Eileen Myles, “Painted Clear, Painted Black,” Evening Will Come: A Monthly Journal of Poetics, no. 29 (May 2013).

3. In the opening pages of Irrational Modernism, Jones declares her indebtedness to a number of feminist art historians whom she admires and upon whose work she is building and extending; this includes Naomi Sawelson-Gorse’s anthology Women in Dada and Irene Gammel’s Baroness Elsa: Gender, Dada, and Everyday Modernity — A Cultural Biography. Published in 2002, Gammel’s biography paints a fascinating, multifaceted picture of the Baroness’s role in the early-twentieth-century avant-gardes. Gammel’s biography served to rediscover the Baroness, and soon after a small collection of her poetry came out: Subjoyride, titled after her readymade poems from 1919 to 1920. In 2011, a comprehensive collection of her writing, Body Sweats: The Uncensored Writings of Elsa von Freytag Loringhoven, was published by MIT Press. A beautiful book of all her writing, it includes her published and unpublished poems, and handwritten manuscripts covered with intricate drawings and diagrams.

4. Body Sweats: The Uncensored Writings of Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, ed. Irene Gammel and Suzanne Zelazo, (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2011), 171.