The Baroness in little magazine history

The Little Review magazine published Dadaist Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven’s poetry during the height of a dialectic phase in little magazine culture when conversations about the nature of literature and “the literary” were ubiquitous. In particular, readers contested the value of Dada poetry and “the Baroness” became coterminous with what some considered the worst of this experimental movement. In January 1922, for example, Harriet Monroe wrote in Poetry that “the Little Review […] is headed straight for Dada; but we could forgive even that if it would drop Else von Freytag-Loringhoven on the way.”[1]Jane Heap, editor of The Little Review, responded in a brief piece entitled “Dada” that “[w]e do intend to drop the baroness — right into the middle of the history of American poetry,” for the very reason that “the Baroness,” whom Heap calls “the first American dada,” represents lived art: she is “the only one living anywhere who dresses dada, loves dada, lives dada.”[2]

The Baroness has been the focus of much cultural study in the last decade by art historians and feminist scholars who wish to reclaim her place as an influential member of the New York Dada scene, but discussions about her poetry are few.[3] With this Jacket2 feature, we further the work done by the editors and readers of The Little Review in the 1920s who sought to locate the Baroness’s poetry within experimental trends, but we also critique the narrative of American poetry history out of which the Baroness’s poetry has often been dropped. We locate and situate her poetry in previous and current literary trends by introducing three previously unpublished poems, new and groundbreaking biographical facts concerning the Baroness’s German poetry, a rereading of her Dadaist poetry that situates it within the frame of feminist performance art, and a contemporary poetic response to her work.

Gender, Politics and Play: The Baroness and The Little Review

True to Dada form, the Baroness’s poems sparked debate by representing and performing scandalous literary performances. For example, the January 1919 issue of The Little Review features the “Letrygonians” episode of James Joyce’s Ulysses, the first episode to be officially censored by the postal authorities in New York because of passages that mock the King of England and detail Leopold Bloom’s memories of an amorous meeting with Molly. Published just a short time later, in May 1919, the Baroness’s poem “King Adam” contains a lacuna masking a bawdy reference to cunnilingus alongside the warning “donated to the censor”.[4] In the context in which “King Adam” is written, the danger of censorship is more than potential: it is actual. The Baroness’s poem calls for censorship by being “vulgar,” enacts it by incorporating lacunae, and comments upon it by directly addressing the censor. The poem engenders the scenario but it also enacts it.

By including provocative pieces by the Baroness, the editors of The Little Review, Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap, placed their little magazine in the center of literary debate. “Holy Skirts,” which discusses sexuality in terms of the Catholic church, was printed in the July–August 1920 issue and represents a poem with an increasingly irreverent sense of play and obvious criticism for more traditional cultural institutions.[5] It is also a poem that alludes to the most talked-about literary court case in history since the same issue also contains a section from the “Nausicaa” episode of Ulysses in which Leopold Bloom has an orgasm while looking up a young woman’s skirt as she leans back to look at a fireworks display. This was the last section of Ulysses to be printed by The Little Review before Heap and Anderson were taken to court and sued over the excerpts. Specifically, the presences of this irreverent poem as well as a photograph of a seminude Baroness on the frontispiece of the same issue in which Heap’s article “Art and the Law”[6] appeared, helped foreground the editors’ belief that the Ulysses censorship trial was about “women’s issues” and “claiming sexual pleasure and agency for American women.”[7] In thinking back on to why she started The Little Review, Margaret Anderson sees dialogue as central: “It was the moment. The epoch needed it. The thing I wanted — would die without — was conversation.”[8] “King Adam” (May 1919) and “Holy Skirts” (July–August 1920) ask general, provocative questions about the role — the value — of women and sex in modernist society, but their presence also creates a space in the magazine in which Heap and Anderson could employ the Baroness’s poetry and presence to encourage, enact, and comment on the controversy surrounding excerpts of James Joyce’s Ulysses published in The Little Review in the 1920s.

Certainly, with Dadaism, the act of art is intricately tied with the artist’s ability to provoke a response from fellow Dadaists and the bourgeois culture. Heap addresses this aspect of the Baroness’s poetry in her 1922 piece “Dada” when she suggests that perhaps Monroe’s critique of the Baroness (described above) is really a defensive comment meant to uphold the more traditional notion of literature to which the magazine Poetry ascribes. Heap asserts that Monroe does not like the Baroness’s poetry because “dada laughs, jeers, grimaces, gibbers, denounces, explodes, introduces ridicule into a too churchly game.”[9] By publishing poems that were, despite Heap’s comments, rejected by the magazine’s editors in the 1920s and by including more recent criticism in this collection, we are employing the Baroness’s poetics to critique the narrative of American poetry history from which the Baroness has often been dropped. The following provides a brief introduction to the three poems that are published here.

“Aphrodite to Mars”

Though the Baroness had written other poems meant to provoke the magazine’s readers, Anderson and Heap began to reject the Baroness’s poetry after the Ulysses trial. For instance, the editors rejected the Baroness’s poem “Aphrodite to Mars” (also called “Aphrodite Chants to Mars” in other versions). “Aphrodite” represents a period of the Baroness’s creative development in which she was deeply interested in gender politics but also interested in what she regarded as the false art of high modernists such as William Carlos Williams. as well as in the modernist trend to employ Greek and Roman mythologies. This poem points to the popular story of Aphrodite and Ares (or Venus and Mars) in which Aphrodite, the goddess of love who was born from the sea foam created by her father Uranus’s cast-off genitals, has an affair with Ares (Mars). Aphrodite and Ares are eventually trapped by Aphrodite’s husband Hephaestus, who creates a web around their bed (one possible reading of the “Flexible tenderness web” in “Aphrodite”) and keeps them ensnared in order to expose and disgrace them before all the gods. Zeus finally lets Mars go at the urging of Poseidon, and Aphrodite is, according to Homer’s Iliad, sent to the island of Kypros, where she is bathed by the Graces.

Though the gods play a significant role in “Aphrodite,” a more humanist perspective on gender and sexuality is emphasized over serious consideration for the myth. Signifying the poem’s irreverence for the myth’s origins as well as high Modernist literary culture, the Greek name “Aphrodite” is erroneously coupled with the Roman “Mars.” In addition, popular slang, including repeated references to Mars’s “blade” and its reception into the “Artistocratic fit” and the “elastic” “Suckdisks” associated with Aphrodite, emphasizes the sexual imagery that was, in the original telling, the plot of serious life-and-death drama. In contrast to the mythological telling, “Aphrodite” reads more as a baudy comedy, a humorous battle of the sexes (or genitals), with the strong “arm” of weapons that Mars brandishes pitted against the “receptive keenness” and “ecstatic elasticity” with which Aphrodite envelops him on the humorously described battle site or “Tournament dale” the “Mattress.” One may easily read Aphrodite’s stance as a recuperative “feminine” elasticity victorious over the pseudonymous “Victor” (Mars) just before the fast pace of this frolicking poem pauses and takes a breath in a beautiful stanza describing the calm seas of azure and the postcoital glow in which Mars lies asleep. Then, quite abruptly, the poetic voice announces “Aphrodite I hail!” as if she had taken both the reader and Mars unawares in this moment of peace. Here we see Aphrodite as victor in her gendered role as “Mistress — mother — / Master — mistress / To / Man” over Mars in his capacity as “Son / Father / Lover / Mate” and, ultimately, in his capacity as “Victor.” Even though its themes of irreverent play and literary commentary would have been familiar to readers who sought out the Baroness’s poetry, the explicit nature of this poem’s sexual metaphors in a time of increasing censorship were quite possibly too extreme for Heap and Anderson. Additionally, the poem’s irreverent take on Greek and Roman mythologies may have been too critical of what had become a deep-seated regard for the antiquities in the increasingly high culture represented by the magazine’s readership.

Dada, the Act of Nonsense, and “Astride”

Tension within the 1920s literary community around the value of Dada art is never more apparent than in the discourse that followed the 1919 publication of the Baroness’s poem “Mineself——Minesoul——and——Mine——Cast-Iron Lover.”[10] The discussion ensued in The Little Review in December 1919 and January 1920 under the title “The Art of Madness” and included Heap, Maxwell Bodenheim, Evelyn Scott, and the Baroness, among others. It was sparked by Heap’s response in “The Reader Critic” — the section of the magazine reserved for reader comments — to readers who thought “Cast-Iron Lover” was written by someone who was in “a condition of disease and mania”.[11] In response, Heap argues that the Baroness is merely “unhampered by sanity” and able to “work” insanity “to produce Art.” Heap calls her work “the Art of Madness,” asserting: “It wouldn’t be the art of madness if it were merely an insanity”: in fact, Heap writes, “Madness is her chosen state of consciousness.”[12] In other words, Heap believed that there was method to and thoughtful craft behind the chaos of the Baroness’s Dada poems. Heap appreciated early what David Escoffery today calls the “rhetoric” of the Baroness’s poems. Escoffery argues that in Dada the “rhetoric of nonsense” is the “key factor determining the character of a performance event,” since it describes that which may be perceived as random or chaotic, as a tactic that persuades audiences to participate and collaborate in the Dada performance.[13] By not making sense, Dada performance breaks through the “fourth wall” of theater, the “wall” that separates the play from the reality or the actors from the audience. By not making sense, Dada poetry and art requires audience participation.

In “Mineself——Minesoul——and——Mine——Cast-Iron Lover,” for example, the Baroness achieves what may be considered a “simultaneous poem” that evokes aspects of tonal poetry by synchronizing the multiple voices of “the self,” “the soul,” and “the body.” A Dada technique used frequently by Huelsenbeck, Tzara, Marcel Janco, Hans Arp and others, the simultaneous poem was traditionally a simultaneous recitation by multiple poets of multiple poems to a live audience. The goal was to create a bizarre effect that appeared nonsensical but ultimately made sense. As such, the simultaneous poem proved the fact “that an organic work of art has a will of its own, and also illustrates the decisive role played by accompaniment,” which represents the conscious will of the artists to structure and make meaningful the combined recitations.[14]

Appearing in a prose-like format that comprises nine full pages of The Little Review, the overall, chaotic effect of “Cast-Iron Lover” is due in large part to its confusion of voices. For example, two of the voices are recognizable in the following lines as “mine soul” (who “touches” through the body’s eyes) and “mine body” (whose “sensual” eyes provide for the soul’s song):

MINE SOUL—MINE SOUL—thou maketh me shiver—thus it can it not be! dost thou

remember that song of his hair which made mine eyes thine fingers?

Thine eyes made mine song—mine body—thine eyes. TOUCH! guard thine eyes—mine

body—guard thine sensual eyes!

Sing thine sensual song—mine soul—thus it ran:

“HIS HAIR IS MOLTEN GOLD AND A RED PELT— […]”

Tonal poetry — which may be defined as three or more voices speaking at once to create a cacophony of bizarre or funny sounds — often employs words that when mixed sound nonsensical. As this poem progresses, the Baroness achieves the same tonal affect on an ontological level by blurring the differences between the “soul” voice and that of the “body” voice, thus creating an intermingled voice that represents an intermingled identity. The body cries “I am tired of wisdom!” The body thinks and is philosophical. The soul speaks and sings and has a “sensual” song and “fingers.” While these two voices are not overlaid on the page, their identities are certainly overlapping. The Baroness further mingles their voices and therefore their identities by punctuating each speech with referents to the direct object of the speech or the “listening” character, set off from the speech by dashes: “—mine soul—” or “mine body—”. While this structure functions to demarcate the speaker, it does not make the cacophony of second person references — “thou” — any less confusing; in fact it adds a ludicrous dimension of emphasis on the listener as the subject of each speech. Making the “you” the primary subject of each “I” statement emphasizes the overlay of identities. In order to understand who is speaking, the reader must pay particular attention to the subject and referent or object of each line:

Mine body—thou maketh me sad—thou VERILY hast made sad—thine soul—! Mine

body—alas!—I bid theee—GO!

THOU—mine soul?!

I—mine body.

Because the reader is forced to pay closer attention, to be an active reader who must order the subject and object of each speech, she becomes immersed in the intermingled identities and voices, thus experiencing the tonal aspect of the poetry.

Finally, though the piece is titled “MINESELF—MINESOUL,” “mineself” is never mentioned in the poem until the poem’s conclusion: “Upright we stand—slander we flare—thine body and thou—mine soul—hissing!— / thus—mine soul—is mine song to thee—thus its end!!” Here, “We” is the third voice — “mineself” — speaking to the referent of the speech “minesoul” and talking about “thine body” (the “minebody” that has been the referent of “minesoul” throughout the poem thus far). All become “We” as the speaker (the “self”) confirms that the poem has been the self’s song to the soul about its codependence with the body. Its form necessitates a performance or reading of the poem since understanding who is speaking is impossible without experiencing the pauses (the dashes and line breaks) that help to impose some order with which the reader may make sense of the chaos. Consequently, the performance of the poem, which relies on splitting the “self,” the “soul,” and the “body,” introduces a tension on the page and the work becomes a simultaneous poem that embodies the reconnection of these forces.

While “Mineself——Minesoul——and——Mine——Cast-Iron Lover” employs the rhetoric of nonsense through multiple, nonsensical voices, the poem “Astride” employs a rhetoric of nonsense through optophonetics. Optophonetic poetry provided a written form for the very popular “sound poetry” that Dadaists Tristan Tzara, Huelsenbeck, Janco, and others performed at the Cabaret Voltaire. In his desire to emphasize the abstract nature of language, Dadaist Raoul Hausman created optophonetics with annotations that used typographic variations to signal certain sound effects, much like musical notation. Kurt Schwitters followed behind, creating what he called Merz, a multigenre, multimedia poem that incorporated optophonetics with pictures, nails, and even sentences, often cut from the newspaper or a pamphlet. The Baroness (who was much enraged by Schwitters’s rising popularity with the editors of The Little Review during the years of her decline from their favor)[15] nevertheless incorporates optophonetics into her own work in the Schwitters fashion. In “A Dozen Cocktails – Please,” she writes: “Serpentine aircurrents -- -- -- / Hhhhhphssssssss! The very word penetrates.” The word, with its low-slung “p” in the middle and its swerving queue of “s,” evokes the penetrating snake it mimics. In “Astride,” the Baroness similarly attempts the sound of a “Straddling/Neighing/Stallion”:

HUEESSUE SSUEESSSOOO

HUEEEEEE PRUSH/

HEE HEE HEEEEEEAAA

OCHKZPN|RPRRRR

HÜ

/ \

HÜÜ HÜÜÜÜÜÜ

HÜ-HÜ!

The “straddling” appears to happen at the end of this section where the HÜ “bucks” from the line. Before this point, the “neighing” begins with softer “s” sounds, and, though the poem is written primarily in English, it includes German umlauts here as if the guttural sound of the “ü” were more precisely the sound she seeks to represent during the act of straddling. The poem concludes with the “shill” crickets indicating that a warning is spreading through the forest. The “HARK!” demands that the reader listen with some care to the stallion’s whinny but the fact that the whinny is in “thickets” invites the reader to revisit those characters on the page that represent the stallion’s neigh, those characters which can be found in a veritable “thicket” of letters — one cannot understand the poem without taking its visual manifestation into account. The poem employs the rhetoric of nonsense and draws in its audience much the same way that “Mineself——Minesoul——and——Mine——Cast-Iron Lover” does. That is, in order to navigate the potential meanings intended by the textual markings and their corresponding sounds, a reader must negotiate both the presentation of the text and the sounds these letters make together by performing these utterances.

Versioning, Transtextual Reading, and “Hell’s Wisdom”

Different versions of the Baroness’s manuscript poems reflect different moments in time rather than a sequence that points to the teleological evolution of a poem. Djuna Barnes once wrote that the Baroness’s manuscripts “are al [sic] sixes and sevens. She wrote very unevenly,”[16] but Hans Richter calls this process of revision Dadaist and describes it as more dreamlike than fancy. “What is important,” he writes, “is the poem-work, the way in which the latent content of the poem undergoes transformation according to concealed mechanisms,” transformations “that work the way dream-work strategies operate — through condensation, displacement, and the submission of the whole of the text to secondary revision.”[17] Certainly the different forms within her poetry and between versions were meaningful to the Baroness. “Hell’s Wisdom,” for instance, exists within alternatively titled versions of the unpublished poems “Purgatory Lilt” and “Statements on Circumstanced Me,” each comprising multiple versions written either as prose in paragraphs or structured into more traditional stanza-and-line formats. The Baroness writes in a note on a version of “Purgatory Lilt” she has included in a letter to Barnes that “This is not a poem but an essay-statement. Maybe — it were better not to print it in this cut form — perpendicular but in usual sentence line — horizontal?”[18] On another occasion, the Baroness writes to Barnes about combining different versions of a poem into one reading by printing her poems “Firstling” and “He” on one printed page: “What is interesting about the 2 together,” she writes, “is their vast difference of emotion — time knowledge — pain. That is why they should be printed together. For they are 1 + 2 the same poem — person sentiment life stretch between one — divided — assembled — dissembled.”[19] As these comments show, versioning for the Baroness was more than a method to arrive at some final, perfect poem. The process of creating different versions and the transtextual dialog that resulted between poems and versions of poems engaged the Baroness and became a method for expression that incorporated significant elements of time.

As a result, reading different poems such as “Mineself——Minesoul——and——Mine—— Cast-Iron Lover” or “Astride” or versions of the same poem in comparison is a useful method for entering into the poetic conversation of a Baroness poem. For instance, one can read the first lines of “Hell’s Wisdom” (“My ‘Derangement’ dwells in absence — as — under circumstances existing — normally — it should be present”) as a reflection of her opinion of Germany by noting that the first line of “Hell’s Wisdom” appears in the second half of “Statements by Circumstanced Me,” after what appears to be a version of “Purgatory Lilt.” This comparison is significant because “Purgatory Lilt” begins with Germany: “Germany’s remain is permeated by decay reek throughout. / Effect of brainstorming backslide —” and proceeds to describe the Baroness’s despondency or the cause of her “derangement” in terms of Germany’s postwar ruin.

Of equal importance is the fact that “Purgatory Lilt” concludes with the Baroness’s more hopeful perspective on America, which she has at the time of its writing left behind forever. Living in late 1920s Berlin, the Baroness often reflected on what she saw as her happier times in the States. Writing to Barnes about a collection she assumes Barnes will be editing, the Baroness encourages her to include “Hell’s Wisdom” because it is “just precisely printing out where I stand in the universe — and why — so precariously!”[20] In her letter to Barnes, the Baroness explains her derangement as the result of her conflicting experience within German and American culture: while “Hell’s Wisdom” speaks of her derangement, “Purgatory Lilt” is “proving my devotion to America — and the rotting — you see — I am deranged — Djuna — temporarily.”[21] Both the devotion and the sense of rotting are present in the concluding lines of “Purgatory Lilt,” which discuss the stifling air (“wheeze I”) the Baroness perceives in the atmosphere of postwar Germany. While Germany’s architecture and its “ghosts” or culture is decaying, the Baroness might take root and conceivably flourish in the “sweet soil” of America. In an undated letter to Barnes from Germany she writes of her love for America:

It is pluck! It is life! The German is not even capable of it! He is in tradition rotten

shrunken dignity a dapper grave — exhausted fool — who dies of “conviction” without

to know what about — he has become too comfortably dull — has forgotten to move —

fight — except in that mechanical war fashion with weapons[22]

Reflecting the Dadaist contempt for stale tradition, the Baroness loves this idea of the United States as a culture that is not so mired in what she sees reflected in the destroyed Germany around her where “dull” and “rotten” traditions have lost their meaning. She perceives America as a culture of action, a trait she admires and to which she aspires. While “Purgatory Lilt” uses America as a trope for a hopeful future, “Hell’s Wisdom” points to the bittersweet hope that retrospective “wisdom” affords. It is ultimately between these two poles (and between these two versions) where the poem is located.

Reading different versions or entirely different poems helps us read a poem like “Hell’s Wisdom,” because in the Baroness’s poetry, a text is often a manifestation of experiments on a theme. This mode of experimentation means that one version’s relationship to another represents an instance of alternative choices rather than a system of rough drafts leading to final versions. For instance, for Dadaists and modernists alike, science and technology functions in opposition to the elements of chance that were associated with creative impulse and everyday lived life. Tristan Tzara writes that “Dada was born of a moral need, an implacable will to achieve a moral absolute, of a profound sentiment that man, at the center of all creations of the spirit, must affirm his primacy over notions emptied of all human substance, over dead objects and ill-gotten gains.”[xxiii]

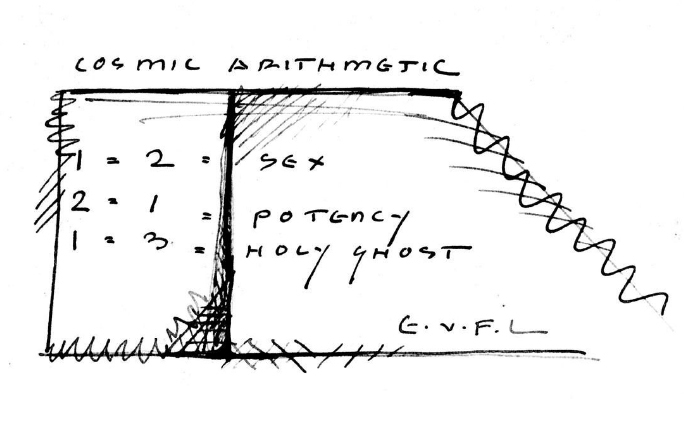

The interplay among historical, personal, scientific, and creative forces in “Hell’s Wisdom” points to themes inspired by the Baroness’s fellow Dadaists, but it is difficult to decipher the abstract logic that the arithmetic in a poem like “Hell’s Wisdom” represents unless one also reads the Baroness’s short unpublished poem “Cosmic Arithmetic”:[24]

Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, Cosmic Arithmetic, 1927. Djuna Barnes Papers, Special Collections, University of Maryland Libraries.

Cosmic Arithmetic

1 = 2 = sex

2 = 1 = potency

1 = 3 = Holy Ghost

E.V.F.L

In both poems, antiteleological perspectives are coupled with traditional uses of science and technology to create striking contrasts. In “Cosmic Arithmetic,” we see some of the same elements that appear in “Hell’s Wisdom,” such as religion (“damnation” and “blood sacrificial”), the sexual potency of “star-shaped” female sexuality (“Lone I — enhanced shrouded earth — by own atmosphere mine self’s own self — out-of circumstance cosmic star - volve revolve — evolve — I do — by starshaped pride”), and the celestial elements of the cosmos (“star,” “moon,” and “sun”). In “Cosmic Arithmetic,” however, the moral absolute of the Trinity is represented in the conciseness that a number can convey—the number three. For instance, in “Hell’s Wisdom,” the same entity is engaged by the three interlaced x’s and the association with X-ray crystallography (“Matter at ever higher level put / Until cristal state —”), a scientific methodology that was discussed by artists in the nineteen-teens since “both cubism and X-ray crystallography rely on the analysis and juxtaposition of two-dimensional slices in order to examine the three-dimensional structure of common objects.”[25] Numbers are similarly abstract representations, and by equating the same numerical combinations (2 + 1 = 3) with terms such as “sex” and “potency,” the Baroness interrogates the “absolute” morality that the Trinity (the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost) represents, given the way the “father” and “son” relationship reflects religious patriarchal institutions in which cultural negotiations between power and gender are played out. In its mathematical articulation of culturally significant words such as “sex,” “potency,” and “Holy Ghost,” “Cosmic Arithmetic” reflects the Baroness’s desire to appeal to the modernist and Dadaist need to express abstract truths with concision. Reading the two-dimensional slices provided by “Cosmic Arithmetic” alongside the more fleshed out response in “Hell’s Wisdom” allows us perspective into the poem’s method for making meaning through abstract variables.

Conclusion

“Ostentatious; Westward:; Eastward:; Agog” (published in transition, June 1929) marks the last poem by the Baroness printed in a little magazine; it also marks a change in the philosophy that governed 1920s notions of experimental poetry.[26] “In 1929 in Paris,” Margaret Anderson writes, “I decided that the time had come to end The Little Review. Our mission was accomplished; contemporary art had arrived; for a hundred years, perhaps, the literary world would produce only repetition.”[27] Indeed the more provocative, informal, and public conversation about poetry between artists had been fading for years, and criticism was becoming formalized in magazine culture just as it would soon become formalized in the academy. Longer arguments about art in The Dial and The Egoist took the place of more conversation-like letters that comprised sections like “The Reader Critic” in The Little Review. In fact, the spring 1925 issue of The Little Review, which featured its last poem by the Baroness, was also the last issue that contained “The Reader Critic” section, the center point for discussion, debate, and responses from readers, editors, and artists. After The Little Review stopped publishing her work, the Baroness concluded that she was not appreciated in New York. She wrote to Barnes, “I have not become ‘known enough’ and so I am forgotten,” because “I had fame that kept me admired, jeered at, feared, and poor.”[28] Finally, with a loan from William Carlos Williams, the Baroness returned to Germany only to discover that her father had disinherited her. Until 1926, she was despondent, selling newspapers on the street in Berlin until Barnes and others raised enough money to send her to Paris, where she subsequently died, in 1927, allegedly by suicide. This collection represents a reappraisal of the appreciation and thought and art that the poetry of the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven inspired and inspires.

1. Harriet Monroe, “New International Magazines,” Poetry 19, no. 4 (January 1922), 227.

2. Jane Heap, “Dada,” The Little Review 6, no. 6 (1919): 46.

3. This scholarly trajectory begins with Robert Reiss’s “‘My Baroness’: Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven,” Dada surrealism 14 (1985): 81–101; Amelia Jones’s Irrational Modernism: A Neurasthenic History of New York Dada (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2004); and a handful of articles written by her biographer Irene Gammel: “The Baroness Elsa and the Politics of Transgressive Body Talk,” in American Modernism Across the Arts, ed. Jay Bochner and Justin Edwards (New York: Peter Lang, 1999), 73–96; “Breaking the Bonds of Discretion: Baroness Elsa and the Female Confession,” Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature 14, no. 1 (Spring 1995): 149–66; “Limbswishing Dada in New York: Baroness Elsa’s Gender Performance,” Canadian Review of Comparative Literature/Revue Canadienne de Littérature Comparée 29, no. 1 (2002): 3–24; and “‘No Woman Lover’: Baroness Elsa’s Intimate Biography,” Canadian Review of Comparative Literature (1994): 1–17. In addition, an exhibition titled Making Mischief: Dada Invades New York, curated by Francis Naumann with Beth Venn, was put up at the Whitney Museum of Art in New York in 1997. The Baroness’s poetry is examined somewhat in Gammel’s Baroness Elsa: Gender, Dada, and Everyday Modernity—a Cultural Biography Cambridge: MIT Press, 2002) and more specifically in Gammel’s “She Strips Naked: The Poetry of Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven,” The Literary Review 46, no. 3 (Spring 2003): 468–80.

4. Freytag-Loringhoven, “King Adam,” The Little Review 6, no. 1 (May 1919): 73.

5. Freytag-Loringhoven, “Holy Skirts,” The Little Review 7, no. 2 (July–August 1920): 28–29.

6. Heap, “Art and the Law,” The Little Review 7, no. 3 (September–December 1920): 8–16.

7. Gammel, “German Extravagance Confronts American Modernism: The Poetics of Baroness Else,” in Pioneering North America: Mediators of European Culture and Literature, ed. Klaus Martens (Würzburg: Königshausen and Neumann, 2000), 65.

8. The Little Review Anthology, ed. Margaret Anderson (New York: Horizon Press, 1970), 351.

10. Freytag-Loringhoven, “Mineself——Minesoul——and——Mine——Cast-Iron Lover,” The Little Review 6, no. 5 (September 1919): 3–11.

11. Quoted in Anderson, Thirty Years War, 322.

12. Heap, “The Reader Critic,” The Little Review 6, no. 6 (October 1919): 56.

13. David Escoffery, “Dada Performance and the Rhetoric of Nonsense: Tearing Down the Wall at the Cabaret Voltaire,” in Images and Imagery: Frames, Borders, Limits: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, ed. Corrado Federici, Leslie Anne Boldt-Irons, and Ernesto Virgulti (New York: Peter Lang, 2005), 3.

14. Hugo Ball quoted in Hans Richter, Dada: Art and Anti-Art (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1965), 30.

15. It is evident from a letter from the Baroness to Djuna Barnes that she saw some of Schwitters’s collages in an exhibition held in New York at the Little Review Gallery. For no apparent reason other than jealousy, she calls his work “utterly mediocre” and “undistinguished vulgar bohemianism” (Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven papers, Special Collections, University of Maryland Libraries, emphasis in original).

17. Richter, Dada: Art and Anti-Art, 80.

18. Freytag-Loringhoven papers, UMD.

19. Ibid., emphasis in original.

23. Tristan Tzara, “An Introduction to Dada,” in The Dada Painters and Poets: An Anthology, 2nd ed., ed. Robert Motherwell (Boston: G. K. Hall, 1981), 394.

24. Freytag-Loringhoven, “Cosmic Arithmetic,” in In Transition: Selected Poems by the Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, ed. Tanya Clement (College Park: University of Maryland Libraries, 2008).

25. Suzanne Black, “Domesticating the Crystal: Sir Lawrence Bragg and the Aesthetics of ‘X-ray Analysis,’” Configurations 13, no. 2 (Spring 2005): 257.

26. Freytag-Loringhoven, “Ostentatious; Westward:; Eastward:; Agog,” transition 16–17 (1929): 24.

27. Anderson, The Little Review Anthology, 349.

28. Freytag-Loringhoven, “Selections from the Letters of Elsa Baroness Von Freytag-Loringhoven,” ed. Djuna Barnes, transition 11 (1928): 25, 26.

Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, Dada dressing, German Arts, and poetry today

Edited by Tanya Clement