A proliferation of differences

A review of 'Troubling the Line'

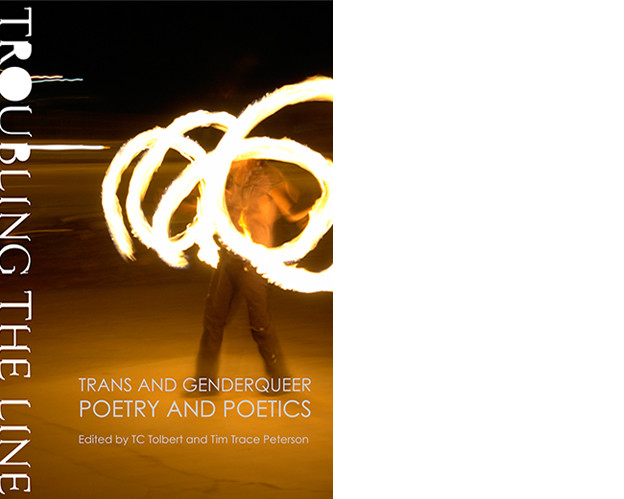

Troubling the Line: Trans and Genderqueer Poetry and Poetics

Troubling the Line: Trans and Genderqueer Poetry and Poetics

In Troubling the Line: Trans and Genderqueer Poetry and Poetics, the first anthology of its kind, editors TC Tolbert and Trace Peterson have included a wide diversity of aesthetic and social perspectives. Poems by Jake Pam Dick, Aimee Herman, kari edwards, Julian Talamantez Brolaski, the two editors, and several others exhibit the kind of strategies — disjunction, linguistic play, disruption of syntax, and derangement of narrative flux — characteristic of innovative poets who, at least to some degree, have been influenced by Language Writing, aspects of the New York School, and the most experimentally inclined American surrealists, post-Objectivists, and Black Mountain poets. The late John Wieners, directly affiliated with Black Mountain, and Eileen Myles, a major second-generation New York School poet, appear in the anthology alongside newer poets. There is a spoken-word poet, Natro, and several poets who seem to have appropriated elements of Slam poetry. Among those who employ relatively direct narrative or meditative strategies are Amir Rabiyah, Ari Banias, Cole Krawitz, Duriel E. Harris, Ely Shipley, Fabian Romero, and Kit Yan.

Many contributors focus on the connections between language and sociopolitical power in both their poetics statements and their poems. Bo Luengsuraswat perceives “languages” as “violent” and declares, “You choose what type of harm you prefer to endure at different moments” and cites as an example the choice to “gender” rather “than being gendered by someone else” (84). Some contributors to the anthology seem to perceive definition as necessary, if problematic, whereas others see resistance to definition as most crucial.

In his lightly iambic, rhymed “So Let Am Not,” the widely know poetry critic Stephen Burt presents a male speaker who wistfully imagines an alternative life as the “flirty girl” he has “never been” (448) but is held back by being “of others, of / responsibilities” and finds the prospect of transition too daunting: “I do not want / to pull up roots, to build a new / high house amid imaginary trees” (449). This individual does not make a decision to choose “reality” over dream/appearance or visa-versa; there are different kinds of “dream” without a touchstone of reality: “So let yourself be / but know who you seem. / Know the difference / between a dream and a dream” (449). Note how the colloquial meaning of “be” — don’t change yourself — allows the poet to avoid establishing a hierarchy in which “being” is worthier than “seeming.” Regardless of biological origins, “seeming” is the important choice to make, and the speaker affirms the primacy of “seeming” over a problematically reifying “being” in the poem’s closure:

Let a man and a boy and a girl whose torso is

a testament to metamorphosis

tell their own tales but as for me

I am not and I am not going to be.

Thank you for listening. Once or twice

I did come close. I was almost a flirty girl. (450)

In “Ready to Know,” a poem in which “all words” are “found in the June 2005 issue of Seventeen,” Joy Ladin imagines the commodity capitalist engine of the production of femininity casting its spell on a man transitioning into a woman and thus critiquing its advertising rhetoric:

Ready to know which girl you are?

Find out while you shave your face

and try to convince yourself

you can look great, hide tummy, enhance bust,

find the best dress for your shape,

exfoliate your past so gently

you won’t even feel

the ambivalence that rocks your body,

leshing out your future, adding curves to your shame. (303)

The ironic underside of Ladin’s uncanny tercets suggests that if the audience for this rhetoric buys the imperative to “say yes to the girl you see” (303), which offers her “up // to the goddess moving through / the guy [she has] been for years” (304), she will fall prey to what kari edwards in “a narrative of resistance” identifies as an “end-game” involving “the epiphany of late Capitalism” — that is, “to be the greatest consumer by buying one’s way into endless cycle of unexamined representations of the grand tale” (323). Even if the “‘I am this _____ (fill in the blank) and I am beautiful and sexy and fine and I am ok no matter what you say’ club” comprises a useful “first step in seeing one’s self other than a formless form situated in social shame,” it is an inadequate “stopping point” (323). Instead, edwards advocates leaning “towards deviation, migration, position shifting, slipping in and out of focus, […] try[ing] to find alliances that go in the same direction by a different track, corollaries that get lost in their own direction,” as “a tool for disruption, activism, acts of personal and public empowerment” (325).

Julian Talamantez Brolaski seconds edwards’s dicta about “disruption”: “Mimesis may be a typical response to the world, but it is the distortions that are provocative” (316), and so Brolaski “distorts” ordinary language in poems like “most honeyed” that shuffle dictions and spellings from different eras, use trans-discourse like the adjective “xir” (neither “her” nor “his”), derange syntax, put various words under erasure, vary spacing within a line, and include superscripted and subscripted parts of words. Here are the relatively “clear” concluding lines of “most honeyed”: “perhaps one does not / not want to be found unsupple in the main and unduly hided / that one ys most of all (the time) w/ oneself” (312).

For many of the poets in this volume, trans-self-identification is not determined by access to advanced medical technology that simply “corrects” the misalignment of the body into which one was born with one’s psychological identification with fixed, finite, “natural” properties of the other gender. Instead, as Peterson asserts, there is a desire for “a poetry with a connection to the biological, but a biological that relies upon neither ‘gender essentialism’ nor reproductive teleology as defining characteristics” (20). Peterson even parodies the limitations of the technology, which cannot always keep up with the vagaries of “the viewer’s perspective,” in “Trans Figures” through allusion to Genesis:

Let there be breasts! (and there were breasts)

Let there be a penis! (and there was a penis)

or at least it looked like it from the viewer’s perspective,

under these clothes. If only it were slim,

with wide hips! (and it was slim with wide hips)

Let there be taffeta, muslin, silk, velvet,

velour, or crinoline: and there were all these things,

in abundance. (467–68)

Through the ironizing of this “lo and behold” exclamatory discourse, Peterson’s speaker implies concern about whether the construction of visual appearance is actually a source of “abundance” or a new paucity. In kari edwards’s poem, “This leftover disruption thing,” being “disassembled,” rather than being reassembled within predicable constraints (“in the contours of contours”), is the demand, a prelude to the emergence of a fiery “impossibility”:

we want the freedom

to be disassembled

freedom from connotations

of the nearly possible

being intoned

in the contours of contours

[…]

we want a combination of

the impossible

dreaming substance

moving in fire

because it’s a condition

in a substance

moving in fire (321)

Citing “critical feminist theory” as being “about challenging gender norms” as arbitrary “social construct[s], D’Lo, a Tamil Srilankan Los Angelean, writes in “Growing’s Trade Off” about being “born female” and “experience[ing] life […] through a masculine-identified female body” (117). D’Lo has “a vagina,” has “not taken male hormones,” and does not “identify as woman or as man” but “as transgender” (117). As for j/j hastain in the poem “Is a mistaken carcass a place of memory?” the question “Is there ever anything new to be written of our genders and sexes as they develop us?” is to be replaced by lovers’ intention “to enshrine masteries of fusion. […] This was the last page of the diary. This more than woman or man or ______” (252). The change from passivity, being “developed” by outside forces, and active “enshrinement” of a mastery of self-styled integration, is most crucial here.

For second-generation New York School poet Eileen Myles, the power of language can challenge foundations of male domination by giving women access to the tropes of male privilege, thus permitting the satisfactions of woman-as-man and man-as-woman. In “My Boy’s Red Hat,” she asks: “Am I a man writing the poem of the woman. I was born male, that was my feeling. I looked at my body and apparently I even demanded a penis as a child. It’s what my mother reports. Do I have one now. Yes it’s language. This ropey poem […] Maybe a poem is the famous detachable penis” (176). Or as TC Tolbert puts in the poem “(ir)Retrieval,” “That the body which is my body is indeterminately” (459).

Another form of resistance to definition and advocacy for complex visibility can be found in Aimee Herman’s “Poetics Statement”:

How to define the need to not be defined. On Monday, see Poet in tie and vest. On Tuesday, feast eyes upon cleavage and whale fat lipstick. On Wednesday, Poet is packing, Poet is binding, Poet is gender concealed. […] On Saturday, Poet is the slash. On Sunday morning, Poet is M and in the evening back to F. (43)

And here is the opening prose-block of Samuel Ace’s “I met a man”:

I met a man who was a woman who was a man who was a woman who was a man who met a woman who met her genes who tic’d the toe who was a man who x’d the x and xx’d the y I met a friend who preferred to pi than to 3 or 3.2 the infinite slide through the river of identitude a boat he did not want to sink who met a god who was a tiny space who was a shot who was a god who was a son who was a girl who was a tree I met a god who was a sign who was a mold who fermented a new species on the pier beneath the ropes of coral (431).

The passages from Herman and Ace’s texts both utilize catalogs to emphasize a proliferation of differences. Herman’s catalog promotes de-definition through shifting images that each appear to encourage a (temporary) definition, except for the ambiguous “slash,” which connotes both androgyny and violence. On the other hand, Ace enacts a kind of regress that is thrown off when the reiterated verb “was” is changed to “met” (going back the verb linked with the initial “I”) and later to a trope of tic-tac-toe, then designations of chromosome patterns. When the “man” meets the “woman,” is he meeting the women inside himself who has “met her” own male “genes” or genes that code the possibility of his being female? Is the process of gender reassignment like tic-tac-toe, but with x’s and y’s rather than x’s and o’s? The nonce word “identitude,” coupled with “river,” somehow sounds more fluid, psychologically appealing, and socially enabling than the historically troublesome “identity.” “Identitude” is both a river and the “boat” on which the “I” “slides”; the fact that the “friend” whom Ace’s speaker “met” wants the boat to stay afloat seems a call for “the infinite slide” to continue indefinitely, perhaps to the point where “a new species” is “fermented.”

If the destabilizing of “identity” into a more welcoming, capacious, transgender “identitude” parallels the destabilizing of monological, wholly instrumental language into poetic discourse sliding toward a free play of signifiers, Jake Pam Dick’s “Jake’s Translit/My Transmanual” is a prime example. Taking up where Joyce, Derrida, Lacan, and other pun-happy literati, philosophers, and psychoanalysts left off, Dick exfoliates her manual of the intertextual while ringing changes on the poet’s first name:

’C ’Cos all Jake now. Except some Franz: free man or French! Jake, Jacques, Jack. Like every transman jack of them — no, like one. Truth jacking logic, speeding off with it. […] But don’t just jack off: jake off. Give a hand job to another or novella. Incestuous poetics: do brothers, sisters. A Jake in the books should be deviant, non sequitur! Transmanual vs. Immanuel. […] Expel, eject, ejaculate, I jake. Females do it also! How sex re-enters. I would enter the girl! Or the boy! Crushed-out sex with other texts: bastardizations. Translate’s not enough; translit is better. With God licks and riffs. Plus a slit. (275)

Can “some Franz” (Kafka, maybe?) — now solely in a textual realm — become a “free man,” no longer enslaved to his celebrated repression, thanks to the verbal guitar-jacking/jaking of the “I jake’s” “licks and riffs”? Notions of “truth” are said to (hi-)jack “logic,” which, otherwise, could be “translit”: “lit” (literature, illumination) across artificial boundaries, as well as the “slit” of the “tran” that can “jake off.” Such an associative logic is not “translation”; to “translate’s not enough” if it asserts itself pseudo-authentically as seamless, “pure” transition from one language to another. On the other hand, sexual intensity engendering textual “bastardizations” fulfills a “transmanual” categorical imperative for ejaculation, whether “manually” induced or otherwise. Not only the determinate male entering the determinate female in a “sequitur” eventuating in “legitimate” offspring, “sex re-enters” in numerous combinations. And “a jake” enters the “box”/“books” only to self-“eject.”

Although this review so far has focused on poets’ treatments of transgender issues, numerous poems on other subjects appear. CA Conrad in the visually subtle poem, “it’s too late for careful,” marshals a rhythmically and rhetorically intense critique of US policy in the Middle East in relation to corporate irresponsibility at home:

killing babies is less

threatening with the politically

correct militia

vices for

the vice box for

wards of

the forward state

who like different

things to kill alike

we CANNOT occupy Wall Street but

we CAN occupy Baghdad (91)

The noun “militia” suggests those to the right of the Tea Party; the term “vice box” indicates the icy doctrine of then Vice President Cheney, probable author of the Bush Doctrine. Also note the play on “wards” (those orphaned by US policy), the “forward” march of overly “forward” (imprudent and rude) military intervention, and the pairing of “like/alike” suggesting a link between a preference for violent action and multiple targets lumped into the same category. Conrad repeats the reference to the sabotage of the Occupy movement later in the poem: “we CANNOT occupy Philadelphia but / we CAN occupy Kabul” (92); “we CANNOT occupy Oakland but / the ghosts will occupy us” (93).

Various poets in the anthology address racial/ethnic transformations in language as well as LGBT approaches to “troubling the line.” Ahimsa Timoteo Bodhrán’s poem “Cycle undone” envisions a highly specific homecoming:

[…] If the Red Sea

could part once more, and Palestinians

return home. Who knows what we would do

if we owned our own lands? Perhaps live

or be free, rather than simply

on sale. If we could feel waves wash up

against us, and not be covered in sludge and salt,

hypodermic needles (we wash out with bleach, take

to the exchange), if dirt were sacred once more. And

water clean. If we were more than a preposition,

conjunction, something to bring others

together. […] (29)

In “A Queer/Trans Womanist Indigenous Colored Poetics,” Bodhrán declares: “I use writing as a tool for collective and individual healing and decolonization, a way of rescripting our lives as queer people of color, mixed-bloods, and women of color, as people who know what it means to struggle, daily, multigenerationally” (34). Bodhran perceives “the mythic and magical in the quotidian as potential antidote to our malaise” and holds that “historical trauma is revisited through the particular site of the body; and (trans)national metanarratives and discourses are negotiated through periods and zones of contact” (34).

Similarly, Micha Cárdenas, who engages in digital technology work on behalf of Mexicans seeking to cross the US border, finds “magic” in the “queer” uses of computer systems. In the poem “We are the intersections,” Cárdenas expatiates upon the late Chicana lesbian Gloria Anzaldua’s poetic/theoretical deployment of the “borderland” trope: “We are constantly navigating the violence of borders of all kinds, / skittering across earth pinging satellites that never correctly know / our exact locations, / for they never know how many kinds of thirst we feel” (395). Cárdenas insists that individuals’ and groups’ multiple subjectivity is a most powerful resistance to the erection and policing of borders: “I am the intersection, of too many coordinate systems to name. / We are the intersections, and we exceed the borders placed on us” (395).

Taken as a whole, Troubling the Line manifests numerous “intersections” that vigorously “exceed” many “borders” imposed on the categories “transgender” and “genderqueer” and those who partly or thoroughly “inhabit” those categories.