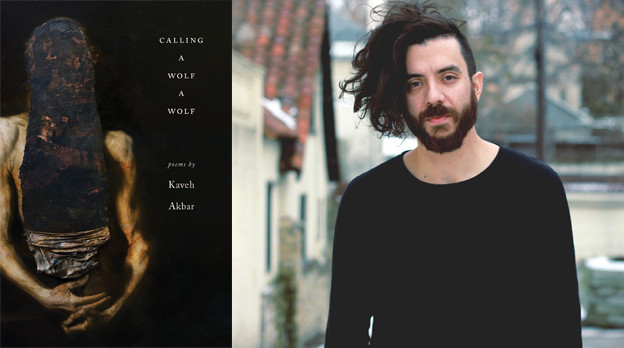

On Kaveh Akbar's 'Calling a Wolf a Wolf'

Calling a Wolf a Wolf

Calling a Wolf a Wolf

In A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man James Joyce writes, “When the soul of a man is born in this country there are nets flung at it to hold it back from flight. You talk to me of nationality, language, religion. I shall try to fly by those nets.”[1] Kaveh Akbar’s Calling a Wolf a Wolf offers various artist portraits of its own, exploring this ground with candor and lyricism, traversing time, culture, and language to create a poetic topography that is both familiar and unexpected.

This long-awaited debut collection by Akbar fulfills the promise of his earlier chapbook Portrait of the Alcoholic, from which several of these poems were culled, and seeds the ground for poems and collections to come, with portraits that are ever-shifting, yet always compelling.

“SOOT” acts as a prologue, a subtle pencil drawing of the collection’s recurring themes: self-destruction, revelation, and renewal.

I keep dreaming I’m a creature pulling out my claws

one by one to sell in a market stall next to stacks

of pomegranates and garden tools.

[…]

[…] Long ago I lived in Heaven

because I wanted to. When I fell to earth

I knew the way — through the soot, into the leaves.[2]

In this poem and the ones to follow, Akbar’s speaker acknowledges accountability as one who has harmed self and others; and graphically describes the intent — “pulling out the claws” — to end such behavior. But the poem also signals the enormous vulnerability of this action: an animal declawed is at the mercy of the world. The imagery of pomegranates resonates on a cultural level — their ruby seedlings play a notable role in a variety of Persian holidays and foods — and also harkens back to the myth of Persephone, marking a life that embraces both darkness and light.

Calling a Wolf a Wolf is divided into three sections — “Terminal,” “Hunger,” and “Irons” — with a denary of poems whose titles begin with the phrase “Portrait of the Alcoholic” dispersed throughout. There’s a suggestion of a reversal of Dante’s Inferno whereby Akbar starts with the dismantling of the self, through a rebirth of mortal desires and delights and, ultimately, a nascent grace. Yet ruminations on the experience of and emergence from addiction are only one layer of these poems. The book strips the self of its protective covering and in so doing gets to the core of what it is to love, grieve, embrace joy, inflict pain, and seek redemption.

The title of the collection is taken from “CALLING A WOLF A WOLF (INPATIENT),” which appears early in “Terminal.” Here the speaker, ostensibly in a rehab center, sits “patiently until invited to leave” while an overactive brain jumps from thought to thought without punctuation, without pause. The structure of this poem, a block paragraph in which phrases are set apart by a single breath of white space, has the effect of equating each fragment with the other, no matter how long or short, comical or somber, excusatory or painfully sharp. After a number of memorable images, the speaker’s final thoughts arrive as hard and jarring as the steady repetitions of a sledgehammer:

[…] I’ve never set a house on fire never thrown a firstborn off a bridge still my whole life I answered every cry for help with a pour with a turning away I’ve given this coldness many names thinking if I called a wolf a wolf I might dull its fangs I carried the coldness like a diamond for years holding it close near as blood until one day I woke and it was fully inside me both of us ruined and unrecognizable two coins on a train track the train crushed into one (14)

It’s no surprise that in dreams, the image of a wolf represents a confrontation with what we fear, perhaps an exhortation to leave the lair of our subconscious and in so doing reclaim individual power. Akbar’s poems question the very nature of a self-portrait: can it ever impartially reflect its creator? Akbar’s depictions of identity often appear like Monet’s multiple iterations of Giverny — perhaps a grittier version of paradise — in dusk and sunlight, through changing seasons and landscapes. Anyone who has woven a shifting identity through sometimes contradictory cultural, geographic, and personal experiences will recognize the road that Akbar navigates:

[…] The lesson:

it’s never too late to become

a new thing, to rip the fur

from your face and dive

dimplefirst into the strange. (21)

These interrelated poems, depicting alcoholism and recovery, suggest that despite a core image, portraiture only scratches at the surface of our countless potentialities. Sometimes we are changed without choice by circumstance; other times we jump headlong into it purposefully. But always, such a portrait is incomplete. Identity — like portraiture — is ephemeral. It can be preserved as a moment in time like amber but never repeats exactly. So, too, self-portraiture is by its nature tainted by the artist’s bias, and no less by the vagaries of memory. Yet these are not soft-focused, filtered selfies that present the subject only in the best light. At times, one has the sense that Akbar displays his viscera under blinking fluorescent lights, ripping up all the images of his former self, a physical and spiritual reformation:

[…] there is

a moment of startle when a thing really sees itself for the first time

a shock of hey me it’s you (43)

Reading this poetic congregation, one considers how a fall from grace is also the first step toward humanity and how the creative act restores us back to divinity. These multiple portraits are also reminiscent of the repetitions one makes in a spiritual life, in mantras, in prayers, to soothe and express devotion:

[…] in Islam there are prayers to return almost anything even

prayers to return faith I have been going through book after book pushing

the sounds through my teeth I will keep making these noises

as long as deemed necessary until there is nothing left of me to forgive (71)

Poets who are bicultural often touch on displacement and exile, but language — and its limitations — is at the heart of many of these poems. What language do we employ when we are speechless with loss? How do we reconcile our heritage, our desires and shames, the disparate pieces that make up an individual? Akbar’s response is to employ a lasered inward eye to refine and strengthen the foundation of the outward I:

I am insatiable every grievance levied against me

amounts to ingratitude I need to be broken like an unruly mustang (23)

In the third poem of the collection, “DO YOU SPEAK PERSIAN?,” Akbar uses the Persian language to underscore how one language, even our native language, can fall short. This is a poet who knows the power of language to obfuscate as well as to connect, and wields that sharp pen with an unsparing self-regard. Here Akbar explores the expanse between content and intent, definition and meaning, intimacy and distance:

I don’t remember how to say home

in my first language, or lonely, or light.

I remember only

delam barat tang shodeh, I miss you,

and shab bekheir, goodnight.

Akbar’s decision to Anglicize Persian words rather than print the phrases in the original Persian alphabet has the effect of drawing the reader in, suggesting that you too can speak Persian, rather than closing us out completely with an unintelligible calligraphy. But much in the same way that the speaker’s automatic responses don’t answer the questions asked by a parent, we can mouth the sounds, perhaps even employ the proper accent, yet still not speak the language with authenticity:

How is school going, Kaveh-joon?

Delam barat tang shodeh.

Are you still drinking?

Shab bekheir.

As a native speaker of Persian, I found this poem particularly meaningful, as I use these same phrases almost daily, and toggle repeatedly between languages in conversation, especially with my parents. How Akbar structures the switch between Persian and English is most intriguing: the parent speaks the language that’s alien to her, and the speaker responds back in the only Persian he has left. Both do their best to communicate over a chasm that’s less linguistic than emotional and employ historically connecting rituals that now separate them further.

I still find that there are many words and emotions that aren’t easily translatable from Persian to English and vice versa. I’ve been told that depending upon which language I am speaking, how I vocalize, even my mannerisms, shift. Bicultural people have the benefit of more flexible citizenship but are also more easily subject to rootlessness. There are times when I feel that, despite the number of languages I speak, I’m still unable to express myself exactly as I want to, as I need to, and Akbar’s poems are particularly adept at describing these nuances.

Do we forget the words we don’t use? Or distance ourselves from the ones that hurt us even to utter, to the people who call to the deepest parts of our hearts? The qualitative difference between communication and connection parallels the gulf between parent and child in this poem — between Earth and Venus, as far as the stars light-years away. We don’t have a direct connection with the stars we see; their immediate reality is lost to us given the astral delay. Akbar’s use of Persian also makes the reader complicit in the push-pull of speaking versus comprehension. The nonnative speaker can sound out and mimic the narrator’s words, but is that really speaking a language? The poet pulls back the veil on the illusion that his words are always illuminating or truthful. Ironically, with the turn of that curtain — both poetically and personally — Akbar the poet offers an intimacy the speaker is incapable of:

I have been so careless with the words I already have

[…]

For so long every step I’ve taken

has been from one tongue to another. (6)

Akbar uses language as both entreaty and absolution. What connects us to ourselves, to each other, to the universe, how delicate is that clasp, how long is the fall, and how do we gain the absolution within the grasp of these portraits?

1. James Joyce, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (New York: Penguin Books, 1999), 174.

2. Kaveh Akbar, Calling a Wolf a Wolf (Farmington, ME: Alice James Books, 2017), 1.