Infrastructure writing

A review of David Buuck's 'Site Cite City'

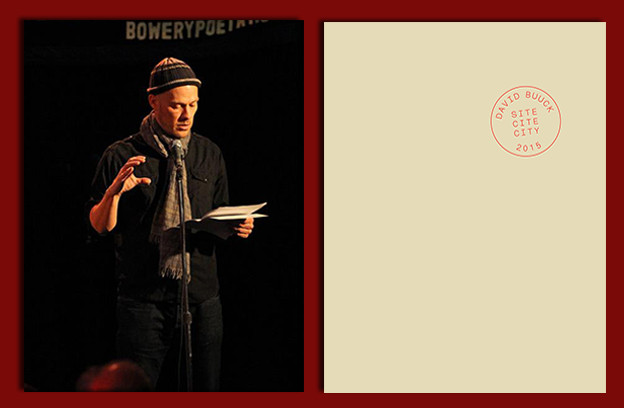

Site Cite City

Site Cite City

“[I]t is precisely a special way of writing that realism requires,” writes Lyn Hejinian in her essay, “Two Stein Talks.”[1] Site Cite City is a book of realism, in the sense Hejinian uses it: realism is the product of a method, of a “special way of writing.” The realism of Site Cite City is directed less at the “pure products of America” than at the infrastructure in which they interact: streets, streetcars, docks, containers, freeways, airport terminals, public buildings, and networks fill Site Cite City. In the book’s centerpiece, “Buried Treasure Island,” Buuck posits that the truth is found “between site and non-site”[2]; infrastructure — precisely what lies “between” the two Smithson concepts mentioned here — is the locus of the real. And not only does infrastructure furnish the subject matter for Site Cite City, it serves as the compositional model for much of Buuck’s work here as well.

Keller Easterling writes in his book Extrastatecraft that “infrastructure space is a form, but not like a building is a form; it is an updating platform unfolding in time to handle new circumstances, encoding the relationships between buildings, or dictating logistics.”[3] Infrastructure is not simply a matter of engineering; it is the new medium of the polity, the place where action and information meet, a “site of multiple, overlapping or nested forms of sovereignty” that behaves like “spatial software.”[4] Infrastructure space is the zone in which the various forces of extrastatecraft — a mix of corporate, NGO, and state actors who compete and cooperate for control — shape the global economic, social, environmental, and even aesthetic contours of everyday life. Site Cite City is a compilation of seven works, each of which reflects strategies to probe infrastructure space and contest the prevailing stories spun by these actors.

“Buried Treasure Island” seeks to remedy the lack of there there on Treasure Island, a manufactured island that sits in San Francisco Bay. Buuck declares his intention to “unearth the secret histories” of the location, mixing journalism, historical essay, song lyrics, photographic documentation, lists, manifestos, and performance notes. “Buried Treasure Island” is an exercise in “tactical magic,”[5] an attempt to rewrite the island itself and transform an existing site into a cite (and possibly a new site). Buuck, an avowed practitioner of tactical magic in the Bay Area, advocates for its use directly in Site Cite City: “Tactical magic will have become the method by which such futural gambits might be flung into the not-yet horizon, chance-chants against the ever-constricted lung capacity and fault lines of other possible tomorrows” (61). In the hands of Buuck, tactical magic is employed to recode the island, extending in a literary direction the projects of environmental artists like Smithson, de Maria, and Matta-Clark — all of whom feature in the book and are “cited” in various ways in “Buried Treasure Island” and even on Treasure Island itself (in the form of signs and marks left on the island). In a triangle-shaped homage to Smithson’s A Heap of Language, Buuck even piles on the page words and phrases found on Treasure Island’s signs. Smithson’s A Heap of Language is a high-concept pun; Buuck’s is a commentary on the use of language to control infrastructure space: the warnings and “no trespassing” verbiage found on Treasure Island emphasize the barriers that serve to prevent a present-day Smithson from effectively transforming it physically and aesthetically.

Tactical magic belongs to a greater “alternative activist repertoire,” a term Easterling uses to describe indirect methods of opposing the authoritarian forces that emerge in infrastructure space via extrastatecraft.[6] An alternative activist repertoire is a means for producing realism, employing a variety of strategies that don’t always enact a binary opposition to authority, but instead work obliquely, highlighting the discrepancies between the stories that the actors of extrastatecraft spin and the real actions they perform. Such strategies include overcompliance, humor, gift giving, doubling, mimicry, and distraction.

“The Alibi” proffers a lyric for the Surveillance Age and is an example of a couple of these alternative activist strategies. The work is (I’m making the assumption that the book’s endnotes are truthful) the transcription of a report by a detective whom Buuck had hired to follow him. The result is an inverse of the lyric poem — “outsourced confessionalism” as Buuck describes it — but not a simple flip from “I do this, I do that” to “he does this, he does that.” “Alibi” actually sits as the third leg in the tripod of which the first-person lyric and Stein’s Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas form the first two legs. Whereas Stein plays the ventriloquist in her autobiography, Buuck narrates indirectly by performing daily activities that the detective transcribes, and then Buuck edits the final transcript (formatting, redacting, arranging, correcting). Buuck, referred to in “Alibi” simply as “Subject,” acts as a conductor, and his hired PI is the player.

The language in “The Alibi” is entirely superficial; most notable are a couple passages in which the detective clearly desires to provide insight into the inner workings of the surveillance subject, only to stop at bland conjecture: “Subject appears to stare off across café as if in thought” (30). “The Alibi” can be roughly divided into three sections. The first and last sections are descriptions of Buuck as he moves around town. However, in the middle section Buuck doesn’t come out of his house, instead standing up the detective for their surveillance “date” so that the detective ends surveillance after a couple hours with nothing to report. The result is a kind of caesura between the other two episodes, emphasizing the emptiness of the lyrical subject and the fact that this detective story is a “nodunnit.”

As a piece of alternative activist strategy, “The Alibi” uses both overcompliance and doubling. In doubling, a double is employed as an imposter, proxy, or alibi in order to ironize a particular situation or relationship. Here, in “The Alibi,” Buuck engages in autoimpersonation: Buuck the surveillance subject poses as a cardboard stand-in for the real subject, and the text acts as a verbal chiaroscuro. Likewise, Buuck’s surveillance subject is a compliant one (there is no equivalent to a “chase scene” or indications of an attempt by Buuck to lose his tail), and it is the act of complicity that adds to the satire. With its ultradocumentary format (the piece is even rendered in Courier font), “The Alibi” is ultimately a performance of caricature — in both the objective and subjective prepositional constructions. It provides a double comment on the presence of surveillance infrastructure and the shallowness of the data that surveillance is actually able to collect about individual subjectivity.

In extending the projects of the Situationists and environmental artists, Buuck makes overt use of autobiography and narrative. In “Market Street Detours,” “The Side Effect,” “The Treatment,” and the already mentioned “The Alibi,” Buuck mixes narrative and autobiography as a means to explore the interface between the individual subject and public space. Often, as in “The Side Effect,” autobiography emerges directly as subject matter. “The Side Effect” is a set of prose stanzas, one to a page, in which phrasal figures ostinato through the stanzas. In the thread of meditations on autobiography that runs through “The Side Effect,” autobiography is described as a negative and passive space, which somewhat tempers the agency of the negative space proposed in “The Alibi”: “Autobiography is that which only gives one the illusion of control” (21); “Autobiography is what happens between the sentences” (18); “Autobiography is what’s left out of the public record” (19); “Autobiography is the space between us” (20); “Autobiography is never about what actually happened, but the muscle memory in the mouth-work of the telling of it” (24).

Narrative as a means to explore the interaction of the individual with infrastructure space occurs most visibly in “The Treatment,” which serves as a sprawling finale to the book — a mix of genres, rife with callbacks to other pieces in Site Cite City, and multisectional. The piece begins, “The containers pile up” (103), and goes on to alternate between narrative episodes, content lists, and reports, divided up into three large sections, which are themselves subdivided. “The Treatment” is a loose first-person dystopian detective story that reads like a Philip K. Dick book mired in bureaucratic red tape. “So — narrative doesn’t arc; it aches” (104), Buuck writes, and the story here doesn’t so much progress as meander in and through various kinds of containers (shipping containers, stores, boxes), the means by which “landscapes process us” (149). Containers even echo in the piece’s format of rectangular paragraphs and stanzas. “No things but in Ikeas,” Buuck quips in “Market Street Detours” (85). The story doesn’t matter here, nor ultimately does the character, because the infrastructure is the story. And the infrastructure space is the narrator, himself a node of communications and containers, watching and watched. Buuck’s writing acts as infrastructure: modular, moving between fact, fiction, writing, and performance.

The interface between individual and infrastructure space is the subject of the writing even as it is explored through formalized strategies of the public practice of writing itself. Buuck composed “Converted Storefront” through accretive performances. The published text consists of Buuck’s transcription of his performance of yet an earlier transcription of an improvised recording of his walk outside of the Oakland gallery, where he then gave the performance. The improvisation that served as the basis of the recording drew both on bits from a review of a cris cheek book (including citations from cheek himself) and Buuck’s impressions of the cityscape as he strolled through the streets (a fairly neat literalization of site, cite, and city). The piece is reminiscent of many of Steve Benson’s iterative and performance-based writing projects, in which composition is enacted as a means to affect the composition itself, often employing types of feedback in order to fold in the environment, the medium, or both back into the text. Recalling the Easterling description of infrastructure space above, the parallels with Buuck’s writing practice come into focus: iterative and collaborative, writing is kept fluid and off-center in order to effectively respond to the occasion.

Site Cite City functions as one of many nodes in Buuck’s network of poetic practice, along with his website, videos, and sound recordings (many of which are “sited” in the book via their URLs) and performances themselves. Buuck’s approach argues for performance as an integral part of composition, and likewise that language art is (or should be) a part of an expanded activist repertoire. “Buried Treasure Island,” as noted earlier, is foremost an activist project, of which the text in Site Cite City is only a part, and describes itself as only one of several “overlapping platforms: installation, guidebook, tour and detour, audio podcast, staged actions, and here in the writing and mapping” (34). Site Cite City’s realism requires an engagement with infrastructure space, just as the “special writing” producing such realism requires that it be part of a larger sphere of activity that encompasses composition, performance, and activism.

1. Lyn Hejinian, “Two Stein Talks,” in The Language of Inquiry (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000),89.

2. David Buuck, Site Cite City (Futurepoem Books, 2015), 34.

3. Keller Easterling, Extrastatecraft: The Power of Infrastructure Space (London: Verso Books, 2014),13.

5. For more on tactical magic see the Center for Tactical Magic’s website.