Writing between

A review of 'Writing Surfaces: Selected Fiction of John Riddell'

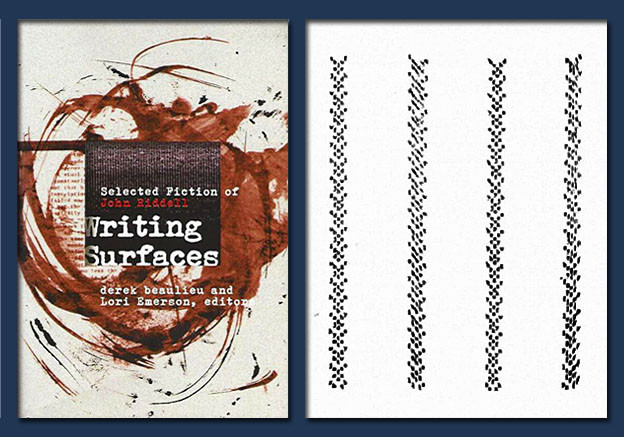

Writing Surfaces: Selected Fiction of John Riddell

Writing Surfaces: Selected Fiction of John Riddell

Writing Surfaces: Selected Fiction of John Riddell presents a sampling of the Canadian poet’s work from 1969 through 1994. Though some of Riddell’s works can be found online, including at UbuWeb, most of his work is difficult to find in print. Writing Surfaces is a concise and accessible introduction to Riddell’s writings, one which hopefully will serve to raise Riddell’s profile among a new generation of readers.

Riddell began publishing work in the 1960s and was a contemporary of — and often cohort with — bpNichol and Steve McCaffery. Like much of the work of Nichol and McCaffery, Riddell’s work probes the interaction between language’s material embodiment and semantic function, the representation of this interaction in and through media, and the effects of this interaction on composition itself. Riddell’s poetics come out of the concrete poetry tradition, refracted through his experiments with the process of composition and through his highly ludic sensibility.

Characteristic of Riddell’s works presented in this collection is the emphasis on fissures, joints, and seams. Most easily recognizable are the visual seams, such as the drawn lines separating and joining text and non-text in “à deux,” the rigid boundaries between neighboring texts/spaces in “letters” and more generally, the boundaries between the legible and the illegible in many of the works in the book. But one also finds thematic seams: juxtapositions of sense and nonsense, fiction and documentary, abstraction and particularity. And Riddell employs seams on the verbal level, perhaps the most literal and obvious example being the word “we” in the poem “we,” which acts as interstitial mortar in the alphabetical series of verbs out of which the poem is built.

In “a note on form” introducing his book Criss-Cross: A Textbook of Modern Composition, Riddell couches his practice in terms of a wider poetic syncretism:

a synthesis may not be desired / is certainly not effected

by displaying both schools under the same roof still

when brot together the prospect of marriage does not

seem as remote as may have been supposed[1]

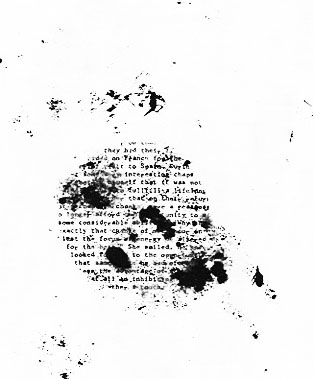

By the term “schools” in the quotation above, Riddell is referring to what he characterizes as traditional and avant-garde approaches to composition. Many of the pieces in Writing Surfaces are exercises in combinations of traditional genres with nontraditional/avant/experimental structures and processes. “Pope Leo, El ELoPE: A Tragedy in Four Letters,” one of Riddell’s more well-known works, is a story told in comic book form using text composed only with the letters “e,” “l,” “o,” and “p.” Another story, “à deux,” is a story of relationships (including perhaps one between two characters named Mark and Katherine) which is disrupted, blotched, and framed by stains and doodles on the page:

(43)

(43)

Some of the marks are reminiscent of rings left by a wet glass, of spills, and of smudges, a simulation of the way the accidents of life shape memory and perception, and consequently, narrative. Another example is “5 ways,” which is also a story of relationships involving multiple couples. The text is printed in long linear fragments of a few lines (sometimes just a single line) that are positioned facing in various directions on the page. The amount of these fragments per page increases through the piece, and the lines increasingly overlap so that the visual interference builds. The reader is forced to try and disentangle the text and piece together the narrative, echoing the storyline of characters trying to understand their own feelings and make sense of their relationships.

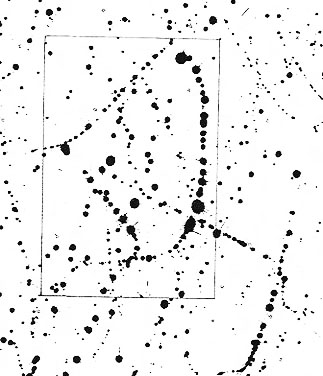

Riddell’s “writing surface” is a heterogeneous one. His model of the poem is a set of language attached to a set of nonlinguistic elements, gathered and held together, producing interior borders that the reader is meant to cross and recross, effecting seams, affecting reading. Riddell’s joining of linguistic to nonlinguistic elements can be read as the contemporaneous reverse of the visual art world’s strategy to incorporate language, which had gathered steam in the 1960s.[2] Riddell recognizes and revels in the fact that language is not a closed system but is part of wider cultural activity. His poems play along with the boundaries between writing and other visual phenomena. In “Pope Leo,” words and line drawings intertwine in and through cartoon panels, drawn characters, and text torqued by and through the lines of the frames. In both “surveys” (excerpted below) and “glass,” bits of language occupy space alongside drops of ink (or is it paint?).

(87)

(87)

In “morox,” a text in a barred-spiral shape (but in a predominately prose-like format in terms of line vis-à-vis margin) spread across five panels, language fades into and out of various forms of illegibility (words turn from the lexical to the nonlexical, type blurs into blackness, letters break free from the bonds holding them to words and float about the page).

Given the prevalence of boundaries and joints, it’s not surprising that the central figure operating throughout Writing Surfaces is the interface. An interface is a threshold permitting a multilateral (often simply bilateral) exchange of information, the seam for negotiation between different assemblages (and often different media). Here interfaces even make appearances in the subject matter of the poems. For example, the window, the architectural interface between the interior and the exterior, dominates the cartoon poem, “Pope Leo,” dotting the facades behind which the action takes place and echoing the panel frames of the cartoon layout. “Criss-Cross” is a narrative constructed out of interfaces: Riddell presents a series of concrete-poetic reproductions of the encounters with language throughout a day in the life of a fictional everyman, Jim. Verbal units within “Criss-Cross” include the face of a clock, the label on a vitamin bottle, and a subway token. Lyrics to the Kinks’ song, “Well Respected Man,” serve as the “text-track” to the piece, running like a film soundtrack along the right side of the page, both accentuating the filmic surfaceness of the page and reinforcing the narrative thread. By taking the language encountered in the world, removing the graphic pizzazz and contextual flavor, and mapping it onto a two-dimensional page in simple courier type — that is, by changing media — Riddell demonstrates the banality of the message and emphasizes the monotony of the working life of the character, Jim.

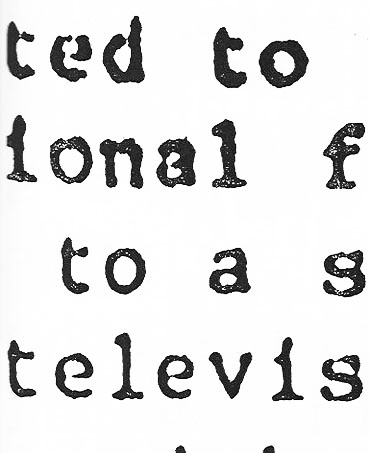

derek beaulieu and Lori Emerson, the editors of Writing Surfaces, describe Riddell’s writing in their introduction as a study in the “writing of writing” (2) — writing taking writing itself as the subject. And their selection emphasizes this aspect of Riddell. For example, a high percentage of the lexicon in the poem “we” is language related: “we demur we denote we deny.” “Criss-Cross” is a piece of writing about how the writing we encounter is presented to us in our everyday experience, estranged both by its translation into a different typography and 2-D space and by its situation within a narrative framework. The pieces “watching” and “in take” both offer ironic takes on the notion of “close reading,” employing xerography and the photocopier’s zoom function. “Watching” (excerpted below) is perhaps the more interesting of the two, a series of snapshots zooming out from a text, so that the letters which at first are mere black figures on a white space come to situate themselves within a text that has to do with television.

(111)

(111)

The piece emulates the experience both of the camera and of the TV viewer on the other side of the interface; the poem is a gesture in which watching and reading are joined in a continuum. Riddell writes with the interface as model of writing, then: the poems often resemble APIs, or application program interfaces, a type of writing about writing (namely writing about the code that a person, the programmer, wants to interact with). His writing, focusing mostly on writing as a visual phenomenon, is often a demonstration of how writing and reading are both forms of the overwriting of the perceiving subject.

Ultimately what Riddell reminds us about writing (and the flipside of the interface, reading) is that they are not independent from other, traditionally “non-writing” activities, whether it’s watching, gesturing, or drawing. While Riddell’s writing is by no means the only to make these points, it is Riddell’s playfulness and craft, on evidence in Writing Surfaces, that make the experience more than just an intellectual exercise.

1. John Riddell, Criss-Cross: A Textbook of Modern Composition (Toronto: Coach House Press, 1977), 7–8. Reissued by ubu editions, 2013.

2. An excellent resource on the turn toward language in the visual arts in the ’60s can be found in Liz Kotz, Words to Be Looked At: Language in 1960s Art (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2007).