Complex orphaning

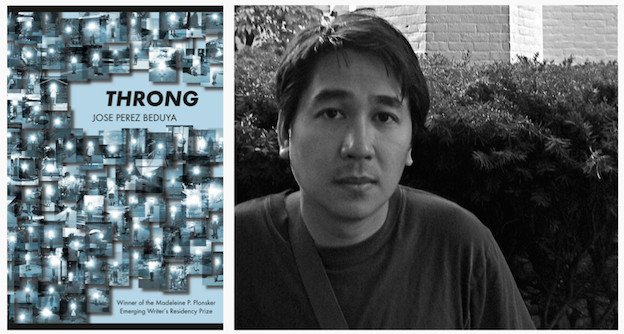

A review of Jose Perez Beduya's 'Throng'

Throng

Throng

One could write an essay placing “The Search Party,” the first poem in Jose Perez Beduya’s debut collection, Throng, in the context of other poems of landscape and complex orphaning, from Blake’s “The Little Boy Lost” to Roethke’s “The Lost Son” to the William Matthews’s poem with which Beduya’s shares a title. Matthews’s poetry, with its wry vignettes and set pieces, would strike most as differing notably from Beduya’s, whose poems more closely recall the oblique precision of Michael Palmer and the lucent spirituality of Fanny Howe, but some lines of Matthews’s poem (“Though we came with lights / and tongues thick in our heads, / the issue was a human life”) aren’t far from moments in Beduya’s “Search Party”:

Our long, stumbling days

Began and ended

With balled versions of the prayers

We were taught in different tongues

Flashes and rustling

The narrative situation in Beduya’s poem, however, is more perpetual than packaged, so rather than elaborating a scene, such lines are its chief substance; Beduya’s lost children — who are also their own search party — find nothing more dramatically significant than “debris” and “notes / with nothing to report.” They are “a people very inside ourselves” who don’t as much disappear into their surroundings as merge with them (“Hills become a part of us”). Throng often marries such atmospheric and epistemological indeterminacy with what, in concert with Beduya’s ellipticism, feels as “clear” and “realistic” as poetry of more heavy-handed dramatization. “Parts,” for instance, swirls with stunned disorientation, yet its location and urgent seeing is steady and precise:

Alone in a night garden saying

I am I am

This empire butchers choirs

Its errors

Displayed as green rooms

Later made raw

Hills in post-production

Later in the poem, the language of “post-production” echoes through snow that is “dead pixels” and a “heart playing its one red loop louder.” As in Andrew Zawacki’s reelingly techno-ecological Videotape, Beduya often approaches the natural through the digitized (“On helmet cam / The night twittering”), at times with overt references to the scripted requirements of representation (“Segue to a change / Of person but exactly / The same scenery”). By foregrounding the construction of the poems, these techniques help one move as quickly as the writing requires. “The Reunification of the Body,” for example, begins by putting us exactly where we are, arranging our posture before our understanding: “Stay down beside your confirmation number / And be someone’s garden.” In some of the poems, such as “Breathing Exercise,” a poem in which every strophe begins with “No” (“No quickness / No razor wire”), the swift alterations of these instructions feels more ritualistic, as though the poems are not only scripting representation but serving as a script for original experience.

The series of brief poems titled “Inside the Bright Wheel” contributes to this mood, offering mysteriously lucid glimpses:

We tremble and kiss

We lie down in riot films

--

Shivering you sit

At one end of a see-saw

While the vast and buzzing

Night

A factory

And all-seeing

God sit opposite

These quoted sections, as well as some of the lines quoted above (“This empire butchers choirs”), highlight Beduya’s talent for swiftly casting industrial settings in visionary terms, for showing how “Tenderized / Post-citizens” can still “keep warm.” I know few recent collections of poetry that so closely explore the ways in which lyrical experience can run through civic life, showing that “we still dream of an ethics” despite varied alienations. This interest sometimes swivels on the juxtaposition of the collective and the domestic (“Random wars while our flesh / Did household chores // The decade leapt / Through curtains of wet newsprint”) and at other times on language with a corporate tinge. Most often, though, it suggests a mythical regard for speech. “We gut our enemies / But speak softly into them,” one poem announces. Another poem, “Revolver,” resembles an origin story that begins in medias res:

Soon after the men

Of our church found trees

Of smoldering meats

In the backyards of our

Married daughters

One lambsman came

Pounding at our doors

To collect payment

We gave him statuettes

Of gold and curdled milk

This concern for ethics brings Oppen to mind, whom Jennifer Moxley mentions in her compact and capacious introduction, and one can also hear his lineage in Throng’s phrasing (e.g., “A cascade of stripes in the museum // A rip waiting to happen / Down the turn-of-the-century dress”). A longer essay on poems of a lost child might also include Oppen’s role as a kind of reverse Pied Piper in “Of Being Numerous,” when he considers younger companions (“The girl’s name is Phyllis — / Coming home from her first job”; “Strange that the youngest people I know / Live in the oldest buildings”). Beduya’s poems can similarly find distinct revelation through the ruination of singular seeing, as in the end of “Revolver”:

We found joy again

And feasted

Without remainder on the other

Side of the ruins

To be on the other side of the ruins, of course, does not eliminate the ruins: they are still right there. We might not even be past them. But we find ourselves beside them, in relation. “You believe you are in the world / Without example,” Beduya tells us in “Noir”; throughout Throng, he shows that such beliefs are themselves telling examples, which makes them no less astonishing and estranging. “Guarding against numbness / We started small fires / Everywhere we went,” Beduya writes in “The Search Party.” The poems in Throng do the same.