Allowing oneself to 'be the city'

A review of 'The City Real & Imagined'

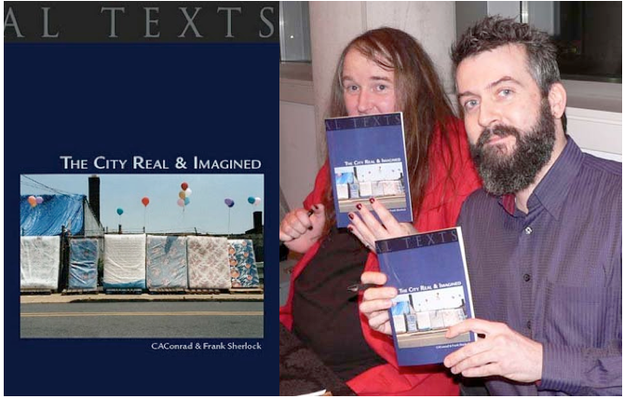

The City Real & Imagined

The City Real & Imagined

(Soma)tic Procedure: Every morning for six days read fifteen pages of The City Real & Imagined as a new and crucial part of your morning routine — whether this be a walking commute, a subway ride cross borough, a bus ride, etc. This addition should feel natural, necessary. Do not be afraid to read while walking — it is morning, the sun is out, people can see you, the streets are watching. Do not read more than sixteen pages — savor the text, do not try to figure out who is speaking, instead, place yourself inside the conversation, imagine your city is the city of Conrad and Sherlock, because it is. Mark the pages you fall in love with — use hot pink flags to help you remember this. At the end of your day, meaning post-dinner, post-work, post, revisit the pages and passages you’ve flagged. Respond to each of these pages or passages in six words. Revisit these words and see where they travel. Compose an “essay” in six parts, using one outside source per part.

***

I. city. shadow. radio. please. working. street.

I can’t help but think about Williams’s author’s note to Paterson —

a man in himself is a city, beginning, seeking, achieving and concluding his life in ways which the various aspects of a city may embody — if imaginatively conceived — any city, all the details of which may be made to voice his most intimate convictions. (xiv)

I think the reason why this book’s opening takes me back to Williams is not necessarily the connection between Conrad and Sherlock’s commitment to place and space, but rather the humanizing and humanist impulse to own and therefore empower the urban landscape by allowing oneself to “be the city.” On the very first page of The City Real & Imagined, we encounter: “dear / impatient / city I / Love?” (7) — an epistolary moment that traverses urban sprawl/spew, with a nod to the chaos we all live amidst, and somehow manage to Love (with a capital “L”). “We are told in many ways that song / is / not enough” (18). The “song / is / not enough” because the song is only one form, one mode of interaction with language and audience. Rob Halpern addresses this move beyond the singular (in terms of author/form/poem/art/space/etc.) as “investigat[ing] strategies for interrupting the reproduction and smooth maintenance of social spaces in and around which lived bodies organize themselves.” The importance of the work that Conrad and Sherlock do, and the idea that they collaborate and move through Philadelphia as two separate bodies, is that more bodies need to be less concerned with “smooth maintenance” and more interested in “interruptions.”

II. decontrol. language. theism. shop. insects. planet.

Too often we forget about the “human” in human geography. This book reminds us that every city is a peopled space. As Carl Sauer writes in his “Foreword to Historical Geography,” “We know that habitat must be referred to habit, that habit is the activated learning common to a group, and that it may be endlessly subject to change.” What Conrad and Sherlock really enliven in their book is this sense of “activated” or “active learning” that is (and should) be “endlessly subject to change.” Cities change. Places change. “Oh bondage up / yours. We echo this in different languages” (25).

These “different languages” might be our bodies, the way these bodies and languages occupy and engage or challenge space. And, these “different languages” might also take into account the many ways that culture is always in flux — even if a culture becomes an accepted part of a city, “these are processes involving time and not simply chronologic time, but especially those moments of cultural history when the group possesses the energy of invention or the receptivity to acquire new ways” (Sauer). We see through this book of collaboration and conversation that invention does originate in the voice of people/the people. We see that we can write our own “cultural history” by engaging physically with our city our planets. “A chocolate ear is sold as The Mike / Tyson Special. A chocolate man I / think is Teddy Roosevelt is nobody / really, but somebody really. / I’m seeing Masons everywhere” (37)

III. station. woman. lollipop. emblem. half-life. queer. (40–56)

By titling this collection, The City Real & and Imagined, it is evident that Conrad and Sherlock are presenting the reader with a simultaneous construction of real physical and social space, while at the same time inviting readers to collaborate in their imaginative re-visioning of that same locale. As Maya Deren writes in “Cinema as an Independent Art Form,” “A truly creative work of art creates a new reality and itself constitutes an experience, in contrast to the merely descriptive effort which produces an existent reality or adventure” (245). Although Deren is writing about film and cinematography, Conrad and Sherlock’s work of investigation and visualization speaks directly to how she constructs the difference between creativity and reality. If a “truly creative work of art creates a new reality,” then lines like “this man this statue keeps me company on a Locust” (44) and “working Elvis into / everything is easy” (47) envelop the reader into the experience of [This] City Real & Imagined. Conrad and Sherlock alternate through the open field of the page, creating a collusion of description so real it can and can’t possibly be so. This book presents a variant and variable experience, offering readers tangibles like “the paint chips that rust / between these fingers / reveal a structural half-life” (49) and “how many poems / did I write on / South Street Bridge / feeling a current / enter our city?” (54).

IV. powder. gurney. milk. polarity. curbline. personally.

Aren’t we all just tourists in our own minds? Aren’t we all just tourists of our own right? Rights? “We meet it simply/by entering an unlocked gate” (59). In an interview that touches on the composition of this book, Frank Sherlock mentions, “the city was a place for [Conrad] to escape to, while this work was a chance for me to re-imagine the city I grew up in.” So, while the two are walking through Philadelphia, the text becomes the walk and the walk becomes the collaboration. Here I’m reminded of Michel de Certeau’s investigation of “walking in the city,” where he writes, “Its present invents itself, from hour to hour, in the act of throwing away its previous accomplishments and challenging the future” (91). Although de Certeau is writing about New York City, he presents us with a description that invokes the amount of movement any given cityscape creates. Because “everyone’s good / old days smells / of a purer state / of tyranny” (60), we know and walk through the changes that surround us, via line breaks, gentrification, the time the sun sets on any given day. De Certeau continues “walking in the city” by taking a closer look at the connection between “power” and “urbanization,” ultimately positing, “walking affirms, suspects, tries out, transgresses, respects, etc., the trajectories it speaks” (99). So, when encountering lines like, “each Philadelphian / makes these streets / by seeing them/with our lives” (69), I can’t help but be overcome by the notion that the civic statement of walking enables the public rewriting of even the most familiar streets. This is activism, activeness, and the repossession of the necessity that we all occupy and embrace a certain public seat. Remember, “Beliefs / even false ones / aren’t mistakes” (63–4).

V. tavern. banjo. housewife. conjurers. relics. earmark.

Thom Donovan writes,

In The City Real and Imagined a polyphony of voices speak through Conrad’s and Frank’s exchanges. Or, to be more specific, Conrad and Frank speak with these voices; such voices are not just ethnographic curiosities but come from people the poets see around, talk with, and with whom they share a conversation. Through this conversation with Philadelphia’s neglected, Conrad and Frank argue for an open public discourse against American hermeticism.

So, when “I can’t help but recite the first / weather and breaking news” (74), the sense the reader gets is that one needs to be committed to the public, as well as to the political. One needs the line break after “first,” emphasizing the power of the recitation, and isolating the too often absurdities of the “weather and breaking news.” It is also important to remember that the location of this text, these walks, lines, is indeed Philadelphia, the “City of Brotherly Love,” the place William Penn promised would bring the rarity of both religious freedom and economic opportunity. Almost 330 years later, Conrad and Sherlock’s words are imperative — “I’m bored with / dissatisfaction / but fear its / dull foe / complacency.” (76–7) And, that they echo Benjamin Franklin’s assertion that “nothing is certain but death and taxes,” indicating that complacency should never be an option because “does the skyline really change?” (88). And, if activism takes place in physical acts of walking and documenting the streets, we must keep in mind David Harvey’s idea that, “the body can then be viewed as a nexus through which the possibilities for an emancipatory politics can be approached” (130). So, power is human, proletariat, “building is built from bone / Skin steams away in no time / but the relics stay around much longer” (86).

VI. stilts. attempt. seductive. purchase. translates. new.

Because the City Real & Imagined is such a testament to the importance of urban landscapes and the way the cities we walk through walk through more than we realize. Because the City Real & Imagined is a text of heretics, hermeneutics, heroicism, as well a daybook of conversation, rare real friendship in action in dialogue. Paul Thek says, “We accept our thingness intellectually but the emotional acceptance of it can be a joy.” This book asks readers to accept the “thingness” of our human bodies, and to let them walk through space and place. Yet, this book also asks that we remember that all bodies matter. That, “it’s chaos / who gets the / earmark / never the / Daily Beauties” (89) or “I am here to be new to / the city that birthed me & new to / this case that has carried me through” (91). The City Real & Imagined is a volume that belongs in every hand on every street in every city. It speaks to us and says, “I will live / with you like / war has finally / ended please / meet me / there.” (31–2)

Works Cited

De Certeau, Michel. “Walking in the City.” In The Practice of Everyday Life. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984.

Deren, Maya. “Cinema as an Independent Art Form.” In Essential Deren: Collected Writings on Film. Kingston, NY: McPherson, 2005.

Harvey, David. Spaces of Hope. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

Sauer, Carl O. “Foreword to Historical Geography.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 31 (1941): 1–24.

Swenson, Gene R. “Beneath the Skin: Interview with Paul Thek.” Artnews 65, no. 2 (April 1966): 35.

Williams, William Carlos. “A Statement by William Carlos Williams About the Poem Paterson.” In Paterson, xiv. New York: New Directions, 1995.

A series of reviews of walking projects

Edited byLouis Bury Corey Frost