A literary walking uphill

A review of 'Not Blessed'

Not Blessed

Not Blessed

1.

So Delilah cuts Samson’s hair and the Philistines gouge out his eyes. Captive, his hair grows back, his strength returns, he is summoned to the temple to provide amusement, and then the business with the pillars. How, specifically, does Samson, eyeless in Gaza, make his way to his appointment?

Parallel translations of Judges 16:26 in whole or in part:

“Samson told the young man” (GOD’S WORD ® Translation, 1995)

“Samson said to the servant” (New International Version, 1984)

“Samson said to the young servant” (New Living Translation, 2007)

“Samson said to the young man” (English Standard Version, 2001)

“Samson said to the boy” (New American Standard Bible, 1995)

“And Samson said unto the lad” (King James)

“And he said to the lad that guided his steps: Suffer me to touch the pillars which support the whole house, and let me lean upon them, and rest a little” (Douay-Rheims Bible)

“And Samson said to the lad who held him by the hand, Suffer me that I may feel the pillars whereupon the house resteth” (Darby Bible Translation)

What is the effect of reading the various translations of the verse in succession? — Who or what rests? Who suffers? What does the servant, young man, lad, boy, look like? What does he feel for Samson, how does he hold his hand, and what does Samson feel for him, being held by the hand, being led, his steps guided, again and again?

Though he never finished it, Ralph Ellison accumulated at least 2000 pages of a second novel. Posthumously edited, condensed, and published as Juneteenth, the publication obscures what its editor describes as the revisions, reconceptions, entirely rewritten and reworked scenes surrounding a black preacher and his light-skinned protégé turned race-baiting senator. Such inclusion of the repeatedly written and rewritten scenes might have loaned more weight to a scene in which the protégé recalls and cannot let go of, can no longer push away the question — “do you think that little boy got killed? …. What I mean is, do you think old Samson forgot to tell that boy what he was fixing to do?”

2.

Jorge Luis Borges perhaps understates the case in a prologue to Kierkegaard’s Fear and Trembling: “He was unusually preoccupied with Abraham’s sacrifice.”

3.

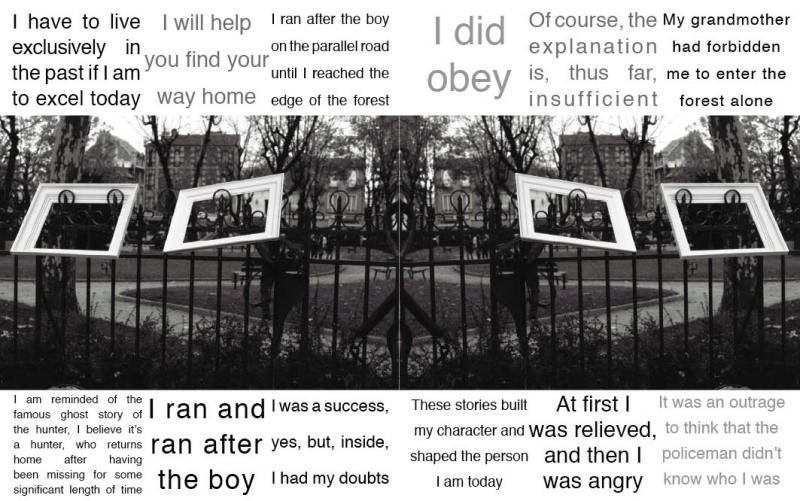

excerpt from Not Blessed, via Les Figues Press

Harold Abramowitz’s Not Blessed is an eighty-one-page preoccupation with an uphill scene in twenty-eight parts, one for each day of February. There is a boy and some kind of doppelganger on a parallel trail, a grandmother, a hunter, a police officer, a hint of scandal, notoriety, fame, resentment, a future, and a sense of mistranslation. It is an ambiguously worrying story. Where Kierkegaard’s Johannes’s initial difficulty in reconciling the story of Abraham, beginning with four attempts to tell it at the beginning of Fear and Trembling, leads to something of a rich affirmation of the knight of faith, Abramowitz’s story, also a literary walking uphill, grows in its repetition ever more ponderous as we come to suspect we will never arrive. At eighty-one short, clear pages, it should be, but is not, a quick read.

4.

William James reminds us how the memory of an insult often hurts us more than it did when first delivered. It grows heavy with us. This is about the obsession with a story. Pondering, like essaying, if traced to its material root, denotes weighing, and also deliberation — ponder the path. The walk of Not Blessed is, generically, a ponderance.

5.

Its preponderant effect is not one of juxtaposition but of accumulation. It seems less to be about repetition, or even repetition with variation, than an overlaying tramp of a sort. Visually, it is less a Warhol silkscreen, an Elvis (Eleven Times), than something like Corinne Vionnet’s superimposition of hundreds of tourist photographs of world landmarks, providing an effect of vague and ghostly margins over a deepening but now supernatural subject.

6.

Walking the same road, part of it well worn, but on this day he walks further than he has ever walked. We get a few constant and sure returns. We will always be walking away, and we will never get too far, we will vary a bit, we might see the other boy. We might understand this dispute with the policeman, the nature of our notoriety and our scandal, our fineness and prominence, but such answers cease to matter — that they’re there becomes somehow comforting and sure.

The book is a constitutional. It has a discipline and it’s good for you; it’s done once a day on the cleanest month that gives us a perfect moon cycle. It has the language of asceticism, detached and appearing to lack vanity — “exercise kept him healthy, trim, and fit,”

There is a correlative to what is called muscle memory in the approach to paths, a habitual understanding of steps, of where to go, where to step, where to dip the leg, feel for a click. You walk from bed to bathroom every night in the dark, and while you cannot recount it now, you’ve never counted the steps, you don’t quite know or can’t tell me what all gets in the way, why you slow down and where, what you’ve stubbed a toe on, what side the light switch is on, whether it’s inside our outside the bathroom door, but you actually know it well enough habitually.

Abramowitz repeats the walk but confuses the muscle in his pronouns, his historical placement, his degree of formality, his verb tenses.

7.

Consider some of the tellings of one recurring incident in a selection of chapters:

1. I came across a policeman who did not recognize me. But I am my grandmother’s grandson and I have lived in the village my whole life, I told the policeman. The question I should have asked was, who are you?

2. […] a policeman suddenly appeared. The policeman, seeing a young boy alone, was immediately concerned for my well-being. The policeman took me by the hand and asked me my name and where I’d come from. I’d grown up in the village, and this exchange with the policeman came as an almost complete surprise. After all, I was one of the sons of the village, later to become a relatively prominent figure.

3. Suddenly a policeman emerged from the forest. The policeman approached the boy. The policeman asked the boy if he was lost. The policeman asked the boy his name and where he’d come from. At first the boy was relieved, and then he was angry. His grandmother was one of the finest people the village had ever known. He himself would grow up and become a relatively prominent figure. He would, in fact, give the village its first measure of notoriety. How could the policeman not know who he would grow up to become.

7. He was almost to the edge of the forest when he suddenly saw a policeman standing in the middle of the road. The policeman gathered the boy in his arms. The policeman spoke gently to the boy. He asked the boy his name where he’d come from. At first, the boy was very angry that the policeman pretended not to know who he was. His grandmother had lived in the village her whole life. The boy would grow up to become a famous and well-respected figure. The policeman gathered the boy in his arms. He spoke to him quite gently.

13. I then remember hearing leaves crack and heavy footsteps behind me. I turned around and saw a tall policeman. The policeman asked me my name and where I’d come from. At first I was relieved, and then I was angry. My grandmother had lived in and around the village her whole life, and I could not believe that I should be taken for a stranger by this tall policeman. Surely he must have lived to regret his mistake. The policeman would have to lie over and over again to avoid telling the true story of our meeting that day by the lake. I would, in fact, grow up and become a relatively famous man. I would, in fact, bring the village its first measure of notoriety.

21. The policeman slung the boy over his shoulder, in the manner of a sack, and carried him home. At first the boy was relieved, and then he was angry.

24. Suddenly, a policeman emerged from the forest with freshly killed game slung over his shoulder, in the manner of a sack. The policeman approached the boy from the opposite end of the road. At first the boy was relieved, and then he was angry. The policeman asked the boy his name and where he’d come from. At first the boy was relieved, and then he was angry. The policeman gathered the boy in his arms. At first the boy was relieved, and then he was angry. How could the policeman not have recognized him. He would grow up to give the village its first measure of notoriety. His grandmother had lived in the village her whole life. The policeman would eventually pay for what he’d done. He would have to lie to his friends at the tavern, he would have to lie to his family. One day the policeman would have to change his story. He would have to lie about what had happened that day in the forest.

8.

In A. K. Ramanujan’s essay, “Three Hundred Ramayanas: Five Examples and Three Thoughts on Translation,” about the tellings of the story of Rama, their transposition and reflexivity of one translation upon another, the way that later Ramayanas play on the knowledge of previous tellings, Ramanujan provides a favorite example from the sixteenth century.

[In this telling,] when Rama is exiled, he does not want Sita to go with him into the forest. Sita argues with him. At first she uses the usual arguments: she is his wife, she should share his sufferings, exile herself in his exile and so on. When he still resists the idea, she is furious. She bursts out: “Countless Ramayanas have been composed before this. Do you know of one where Sita doesn’t go with Rama to the forest?” That clinches the argument and she goes with him.

9.

“There is a version of events that will haunt us even in our darkest hours.” Not Blessed seems also about the utter untestability of recalling a story, an incident, how we saw it, what we felt of it, what it did to us, what we remembered at the time, what memory was like before such a dream, such an incident — the impossibility of verifying a dream.

Maya Deren wrote of her film, Meshes of the Afternoon that it was “concerned with the interior experiences of an individual. It does not record an event which could be witnessed by other persons.” The subconscious, she writes, “will develop, interpret, and elaborate an apparently simple and casual incident into a critical emotional experience.” In this way, Not Blessed attempts to elaborate the formality of the eulogy.

The iterations are also an accumulation of threats. Deren’s Meshes — a curved road, a telephone, a breadknife, oblique disfigured reflections in the knife and mirrored face of the hooded figure, exhausting disorientations in what is really a short piece even when considering all its variants — tires us. The accumulating Mayas, asleep, at the window, translucent in the window’s reflection, watching out the window yet another Maya chase the elusive figure, the last Maya then climbing the stairs to join the others and we await the next iteration — knife, stairs, key, path, stairway to the left. Abramowitz’s Not Blessed gives us a kindred exhaustion.

10.

Iteration is dangerous in literature. It suggests that prophecy is not ingenuous. It suggests lifelessness — “the lifeless iteration of misunderstood doctrines and rites, which kill the soul” as Sarah Austin translates Leopold Ranke’s History of the Reformation of Germany. The ingeminate tale of a boy walking from his grandmother’s house feels scandalous because of its rehearsal and search for the right words that don’t exist because it must all be a lie.

This unusual preoccupation with what we can recognize as a scandal is at the heart of Not Blessed — also an unusual attention to the minor and marginal small triggers of a scandal that emerge prominently because of the form Abramowitz’s book takes. Whatever is new in each piece catches us. Abramowitz takes his book’s title and epigram from Jeremiah’s complaint, where, lamenting that he was born, he curses not his father, not God, not his mother, but the man who brought his father the news that he was born — the unusual preoccupation of a prophet with a newsman. Jeremiah is accused for a false prophet bringing the bad news of Israel’s impeding enslavement, and bitterly walks the streets with a yoke on his neck to mock his own people who will not hear him.

The repetition of Not Blessed, in its mix of mythic languages — old fishing village and the wisest of women coupled with a dishonest boyhood in the backseat of a car — makes us attend ever more vaguely to the nonrecurrences in each telling, and these will not leave us alone.

A series of reviews of walking projects

Edited byLouis Bury Corey Frost