'Tenzone' interviews John Wieners

Note: I first discovered the poetry of John Wieners, seminal Boston poet and peripheral member of the Beat generation, during my undergraduate studies at the University of Massachusetts. As I continued my relationship with his poetry, the idea further cemented in my mind of the solitary voice, becoming clear to me that the work Wieners has amounted through associations, with Charles Olson and the Black Mountain school, with Ezra Pound in Spoleto, Ginsberg in New York and among friends in Beacon Hill, is of significant and lasting artistic achievement. Throughout his career, Wieners’s writings have been overshadowed by the more mainstream success of his old friends, creating for us, the students of the Beats, a kind of “diamond in the rough” presence on the fringe of contemporary American Literature.

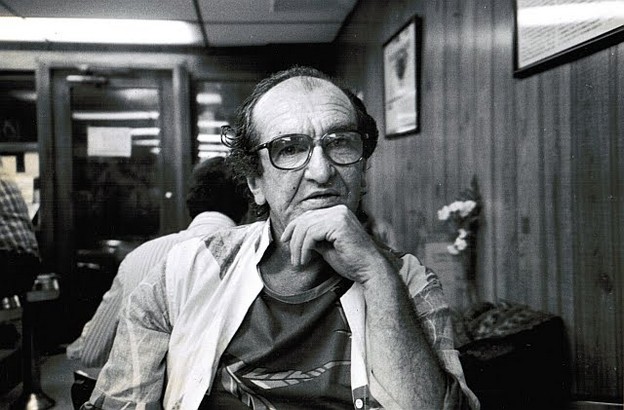

We met on Joy Street on Beacon Hill, January 1993, at the apartment of Jack Powers, a mutual friend and organizer of the Boston Stone Soup Poets Group, and took our places in the front reading room with a surplus of cigarettes, wine, notepads, and questions. We found Mr. Wieners to be comfortable, unrestrained, dressed simply in a sweatshirt, casual slacks, worn-down shoes, steadfast in mind and manner.

Steve Prygoda: Did you grow up in Boston?

John Wieners: I went to school in the South End, Boston College High, right off of the City Hospital.

Prygoda: Is it still in the same place?

Wieners: Well, no. It has moved to Dorchester. I went to Boston College in the fifties before I moved into the city as a grown-up. I was worked over a couple of times while I was still at school, coming down Commonwealth Avenue, so I’m not crazy about the place (BC).

Prygoda: What made you want to become a writer?

Wieners: Immortality, in the sense of living after one’s own time has run out. The paintings will endure; they’ve lasted for, oh, ten centuries. They bring the artist back to life; they hold the proper names of Asian into appearance.

Prygoda: It was at Black Mountain where you first began to develop your own voice and place within American poetry. Who was with you there?

Wieners: The most friendly sort that came out of that experience was Jerry Vanderwile. Do you know the name? He has since slipped from the world’s esteem. He was my sort of person.

Prygoda: How long were you associated with Charles Olson?

Wieners: For about fifteen years?

Prygoda: Did you stay with him while he lived in Gloucester?

Wieners: For suppers, breakfasts, overnight.

Prygoda: Was he doing his Maximus series then?

Wieners: Yes, he had many disciples.

Prygoda: Do you think that is harmful, the “cult of personality”?

Wieners: It is if the person has died, and become ill … that they have been hypnotized through a Danish theologian, that he wasn’t … whose work I am not too keen upon, I don’t know that he is actually aware that he wrote that book, that one anyways.

Prygoda: Do you think Olson was an important presence on the US poetry scene?

Wieners: Yes, I think he swayed thousands, the masses, to become attuned to themselves — sight, hearing, sound, lips, tongues, sort of thing. It comes down to the child, or elementary lessons.

John Wieners’s career as a poet began on the West Coast; a little-known 1957 publishing credit finds two of his early poems in the Chicago Review, an issue focused on the eclectic and vital “San Francisco Scene” including work by Kerouac, Ginsberg, McClure, and Ferlinghetti. A year later Wieners’s first book, The Hotel Wentley Poems was published — lean, personal modern verse bristling with nervous spontaneous energy and Keatsian eloquence. The young poet’s life was off and running.

Prygoda: Do you think the Beats, as they are called, were that big an influence on American writing?

Wieners: Not as big as ten centuries of classical painting. (Anyways) It was just a phrase, a title. I think we got it from the Russians … when they launched the satellite Sputnik in the late 1950s. I think that’s what really popularized the name Beatnik and then shortened by the press and others to just Beat.

Prygoda: When did you first meet Allen Ginsberg?

Wieners: Was it Finnegan’s Wake? A play very well done at the YMHA Auditorium. It was that evening, after the performance, we shared a taxicab over to one of the bars. I got to know him for a nightcap, to a hotel. I can’t remember where we stayed; the director had a car waiting, and he (Allen) made his leave.

Prygoda: If you were to contrast the differences in style between Ginsberg an Olson, in weaknesses and strengths …

Wieners: They were innovators, with style, with character. And Allen, his work will have relevance today and tomorrow.

Prygoda: And Ezra Pound …

Wieners: Ezra Pound was quite a foreboding figure. I met him during the same week we went to a play by Pinter, in Italy. He was in town for the action, to see the Swedish Ambassador, the Czechoslovak, the Russian. These were the men who intrigued him, as melodramatic figures. His world needs melodrama.

Prygoda: Why did you say he was foreboding?

Wieners: He was so small, I think, in his attitude toward reality, as if he had been blanched to an exceeded condition of intelligence. As I have thought of him frequently afterwards, shown in his makeup, do you believe poets should wear makeup? Well, I do worship him.

Wieners found little to do with the mighty forces of literary academia, and chose a life away from the scholarly advancement of his peers. Black Sparrow salvaged over thirty years of John Wieners’s poetry from the jaws of obscurity and published Selected Poems 1958–1984 in 1986. The poet settled into the cobblestones of Beacon Hill, content to live out the remaining years as a Boston poet, contributing sparingly to local literary causes while writing occasional verse, contemporania, thumbnail sketches of the oddities of life set to words, and a play is also currently in the works.

Prygoda: Last year you had a piece published in The Paris Review; am I correct? I’ve had a bit of trouble finding it …

Wieners: A few squibs about … I’m glad they take my stuff out of circulation. They realize that it is not to be discerned. You can’t look in on one’s neighbors.

Prygoda: Were you aware that The Hotel Wentley Poems (1958) would create the amount of impact they did?

Wieners: [Long pause.] I don’t think they have. I certainly don’t want them to.

Prygoda: Why?

Wieners: Well, I used to take the trolley into Boston a lot, in the evenings, go downtown and have a couple of beers. I was so nervous ever to be seen by somebody and have them raise an eyebrow against me that I … shun … having notoriety attached to that area of income. It wasn’t that much but …

Prygoda: More a collection of private thoughts to be shared among friends?

Wieners: That’s what they claimed, yes; more to counteract a bankruptcy claim, period. It’s important to know, and thank you for inquiring about it. That was main purpose and reason.

Prygoda: Well, you got some many beautiful lines, I keep coming back to “I am engaged in taking from God his sound” from “To A Record Player.” Can you tell me about that one?

Wieners: Well, I was so hopped-up. I’ll have to have another beer to answer that!

The evening came to a close and we made our goodbyes, with a smattering of camera flashes and a book to be signed, another bar to visit and begin to unravel the past few ours of conversation with, in Allen Ginsberg’s own words, “one of the ten greatest American writers living today.”

Tenzone wishes to thank Jack Powers of the Boston Stone Soup Poets, who made the evening’s transactions possible.

Edited by Steve Prygoda