Sound I polypoetry

Maja Jantar in conversation with Oana Avasilichioaei

Editorial Note: This interview is part of a feature curated by a.rawlings; entitled “Sound, Poetry,” it began with a request for material on sound poetry as it is currently being practiced in northern Europe. “Sound, Poetry,” however, accomplishes so much more than reportage. Poets from Iceland, Belgium, Finland, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom converse with a broad array of Canadian interlocutors; some have even created new work together specifically for this feature. Here, a.rawlings explains the project:

A term like “sound poetry” may no longer adequately contextualize or clarify what it is intended to represent. It seems a useful moment in the history of this term to reflect on what it means, conjures, describes, encapsulates, and wishes to hold within its reach. It seems personally useful to reflect on the relationship between gender and sound poetry. It feels politically responsible to consider this term in relation to geography.

The wealth of text, audio, and video recordings assembled for this feature is astounding in its range and richness. Accordingly, the five interviews will be published individually in Jacket2 over the coming months. — Sarah Dowling

Maja Jantar [left] and Oana Avasilichioaei [right].

Maja Jantar is a multilingual and polysonic voice artist living in Ghent, Belgium, whose work spans the fields of performance, music theatre, poetry and visual arts. A cofounder of the group Krikri, she has been performing individually and collaboratively throughout Europe, and has been experimenting with poetic sound works since 1995. Jantar often collaborates with Crew, a theater company operating on the border between art and science, performance and new technology, as well as with actor and director Ewout d’Hoore. She regularly performs with Belgian poet Vincent Tholomé, with whom she has also given workshops on language and sound. Jantar recently performed with Vincent Tholomé and Sebastien Dicenaire at the Centre Pompidou in Paris for the Bruits de Bouche Festival.

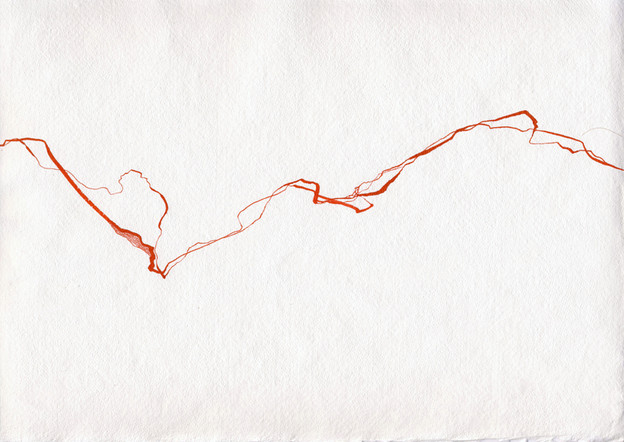

Jantar has directed ten operas, including Monteverdi’s classic Incoronatione di Poppea and Sciarrino’s contemporary Infinito Nero. Her visual poetry has appeared in publications such as Zieteratuur (the Netherlands), and her visual artwork has been shown in several exhibits. An ink-and-paper selection from her “Lilith” series was recently exhibited at Kunsttempel Kassel (Germany). Jantar continues to collaborate with Canadian poet and interdisciplinarian a.rawlings, and the Berlin-based Hybriden Verlag will soon publish a CD and a book of her visual and audio work.

Oana Avasilichioaei’s work forages into geography, public space, textual architecture, multilingualism, translation, and collaborative performance. In 2009, BookThug published her Expeditions of a Chimæra, a collaborative work with Erín Moure that performs the book and translates its authors. Avasilichioaei’s feria: a poempark was the inspiration for and subject of a short film by Montreal artist Thierry Collins (2008). Avasilichioaei’s recent projects include The Islands, a translation of Les Îles by Quebecoise poet Louise Cotnoir (Wolsak & Wynn, forthcoming 2011), as well as transformations of some of her texts into performative aural works. Though she typically lives in Montreal, Avasilichioaei was the Markin-Flanagan Writer in Residence at the University of Calgary for 2010–2011.

This interview was conducted in October 2010 via email and audio — “Interdeff, Interview for Jacket2,” June 1, 2011 (7:51): MP3

Oana Avasilichioaei: You refer to some of the work you do as “polypoetry,” so perhaps you could begin by discussing how you would define this concept vis-à-vis your work. Perhaps you could also discuss how you define “sound poetry” and what evolution or process might exist between “sound poetry” and “polypoetry.”

Maja Jantar: Polypoetry for me, and for how we in the group Krikri are using it, is a way to define many different styles and kinds of poetry — polypoetry — so we intend the word very literally. Whereas sound poetry would be more directed towards the sound element of poetry, polypoetry could also mean visual poetry, electronic poetry, installations, anything poetic.

What I do is poetic; it’s not always poetry in the traditional sense, but I work with the matter of something that is poetic. And I think poetic is something that is in your mind, something that you see, perceive, a way of looking at things. So it’s trying to find that way of looking or listening and trying to bring that out in a work.

Avasilichioaei: I am interested in your relationship to language and translation within your poetic/sonic practice. Many of your performances/songs/videos are polyphonic as well as multilingual. In moving between sounds of various qualities and lexicons of varied languages, what is the function of translation? Are lexicons from different languages used for their sonic or denotative qualities, or both? Is there a translational process at work as sound morphs into language or language morphs into sound? If so, how would you describe this process?

Jantar: I am really interested in language and translation. This is something that comes out in some of the collaborations that I have done. For instance, in working with Vincent Tholomé we made one piece called “Traduc” (“Translation”) where he reads a French text and I improvise on it by translating it simultaneously into English, German, Italian and Polish, which results in a lot of funny twists of meaning. He works with meaning and its different layers, writing mainly in French and using a lot of repetition. In this way, his work evokes an oral tradition, and it’s very easy to simultaneously translate because it repeats.

In my own work, I don’t really work with translation as much. I am more interested in the specific sounds of different languages and their distinctive emotional charges. Of course we all know that certain things can only be said in a certain language in a way. But the sound of your voice also changes from language to language and that is very interesting to me, especially in performance, where the sound of your voice is what actually communicates. It’s not what you say, because you can say the exact same words in many different ways; rather, it is the way you say the words that communicates. So in using a specific language, even if the audience doesn’t understand the words, they do understand a specific meaning — not the sense of the words, but the sense of the voice.

As for language morphing into sound, I like that game. I like the game of breaking language down into something else, making it dissolve or making it go into something more primal.

Avasilichioaei: So what are some of the techniques you use to “dissolve language”? How do you make it more “primal”?

Jantar: One of the things would be to take the material of the words and treat them as sound components, break them up into syllables, work with the syllables, or focus on the consonants or the vowels, stretching, shortening, repeating, depending a bit on what atmosphere or on what meaning they need to have in the performance. For instance, the “KIRKJUBAEJARKLAUSTUR” performance that I did with Vincent Tholomé and Sebastien Dicenaire [see below] starts by breaking up the word kirkjubæjarklaustur, playing with the fact that it’s something not easily pronounced in itself.[1] We chose to mainly work on the consonants, creating an explosive cloud of sounds that actually gives birth to this word. In contrast, later in the performance we use the vowels to create the illusion of flying over a landscape or a city, using the vowels to create this aspect of planer in French, of hovering, using overtones as well to create an atmospheric element.

Another possibility in visual work and electronic compositions would be to layer words on top of each other, use them as building blocks and as matter for their sound, their textures, somewhat for their emotional connotation but mostly as sound material.

Avasilichioaei: Do you think there is a connection between your multilingual approach and the European context in which you live and work, and if so, what is that connection?

Jantar: I have never thought about this before, but I think you have a point. The fact that there are so many different languages in such a small geographic area does make it very easy for me to use different languages. As a child I traveled a lot. I was born in Poland and spent a couple of years in Holland, a couple of years in Austria, some time in England, and ended up in Belgium. My mom worked in the cultural realm and we had friends from everywhere: in America, places in Europe such as Italy and Germany, so all those languages were spoken in my vicinity and I had to switch languages all the time. It became something very natural and logical. And there is an emotional connotation to a language, so when I talk about my family in Poland, like my grandmother, it’s easier to do that in Polish. When I talk about something emotional in my personal life, strangely, it’s easier to say it in English than in Dutch, partly because Dutch has a very matter of fact way of being and sounding.

Avasilichioaei: Do these varying kinds of relationships to the different languages that you speak affect which language you choose to work with in a piece, or which language you choose to break down into something else? And have you ever created a piece using non-denotative sounds as way of creating a new type of language?

Jantar: The emotional resonance definitely impacts my choices in language but it’s not only that. Sometimes, when you work with particular material, the language is already part of it. There is this transcript of an oral judgment that I used in my piece “paralipomena” [see below] — I found the transcript in English, so that determined the language. I would not translate it into another language because of the emotional charge that the other language would give the English transcript.

Using non-denotative sounds to create a new language is definitely something that I have done and love doing in instant improvisations and performances, because it’s something that is very natural. This speaks on a different level than words and meaning, but it definitely conveys something. I have, for instance, a piece that uses only the play between “rz”, “sz” and “cz”, which are Polish sounds, to create a rhythm, playing around with dynamics and speed, in essence, working with them musically.

Avasilichioaei: I am also very interested in your compositional process and in the relationship that you see between composition, improvisation and performance. How do you negotiate these states?

Jantar: It’s an exchange between the three elements. Performance and composition go together because the performance itself is composed, not just the text. Lately, I have begun using the term instant composition for a series of performances that I have been giving, meaning that I use a set structure and improvise within it. For instance, I’ve been working with the concept of “weiß” [white] [MP3], using three different states of whiteness: bone, milk and salt. I then use each of these elements to create an improvisation, and within each element I have texts that I can use if I need or want them. On the other hand, I can let the performance itself decide for me whether or not I use them. I decide beforehand that I will sit on the floor, that I will have some visual aid or score before me that I can use or not use, as well as my book with the texts that I will probably use. The idea of the instant composition rests on the fact that those things are preset. Within that frame I am completely free to improvise, but I don’t feel the panic that I have to improvise for the entire half hour or hour. I have my structure to be free within and I have my visual score, so if I run out of breath or things to express I can go back to the score for inspiration or stimuli. So at this time, that is my relationship with composition, improvisation and performance, but in the past, I have used those three elements in many different ways.

Avasilichioaei: You have worked a great deal in collaboration with other artists/performers. One of the things that collaborative work does so well is it disturbs the idea of intentionality and single-authorship. The work can no longer be located within any one body but instead exists across bodies and localities. Can you discuss some of the significance you see in doing collaborative work and how such work impacts your own practice? And do you think that collaborative work has some necessary relationship to the contemporary moment? Do you think that it has the potential to respond in a crucial way to the contemporary moment?

Jantar: Yes, absolutely, I think that it has. If you look into the past at the romantic idea of an artist creating from himself, from his tortured self, that all inspiration has to come from this one person, this one tortured soul that spills out over the work, then I think we really need to get out of that idea. Other cultures have different perspectives, luckily. So collaborating might definitely be a key to that.

As for my own collaborations, I have always found them extremely inspirational. What I have always liked about them is the fact that it is not me. Together with somebody else, you do something you would not normally do, in the best sense. You get something out of yourself that you would not be able to get if you were alone. You also get to lock onto the energy of somebody else, get into a different stream that can lead you someplace you have never been. As for the authorship element, it’s tricky. It’s not tricky simply because of the ego of artists; actually the people I have worked with have no problem whatsoever with coauthorship, but it is the outside world that does. People somehow always need to have one name behind a project. I worked with theatre actor Ewout d’Hoore on a performance called “Eden,” and because it was in a theatre context and he came from a theatre school, it was very hard to promote the concept that this was a duo performance, that we had thought of it and made it together. And the problem was not between us but coming from the organizers, the newspapers, people around us. The question of collaboration doesn’t even arise; it’s simply assumed that one person should be the author/creator/generator of the concept, which is ludicrous. This is just one example, but I have seen this happen quite a lot and I wonder how it is possible to break that pattern, to make it more acceptable. I guess artists will have to lead the way on that one.

Avasilichioaei: Perhaps the group Krikri might lead part of the way. Can you talk more about your involvement with this group? How did it begin? Who is involved? What are you exploring as a group?

Jantar: Krikri is a group that has a very flexible way of being. The core is formed of three people, Jelle Meander, Helen White, and myself. Then there are a lot of satellites around it, people who perform with us or help out with different aspects when we organize our festival. For instance, we usually work with a visual artist who will create site-specific work to bind all the different locations where the performances are held.

In terms of collaboration, we all have strengths in different fields, which makes it very interesting to work together. All three of us write solo work but we also write work specifically for the group, or to be performed as a duo or trio. So we explore all kinds of possibilities within collaboration, sometimes it’s just somebody imposing something, written out as a score, and sometimes it’s just a thread, a thought, something that develops and takes us to places where both collaborators have never been.

Avasilichioaei: As someone who has worked collaboratively, I am aware of the exquisite risk and productive joy involved in it, though this may not be so obvious to those who have not had the opportunity to work in such a way. So can you also talk more specifically about what is involved when you work collaboratively? How do you take a work from the initial idea to performance? What are some of the allowances that you make? Some of the risks that you take?

Jantar: I think the risk lies at a very human level. You start to work with somebody because there is a personal interest in exploring what that person is doing and a curiosity to see what will happen. It’s a bit like alchemy for me and the risk is that you never know in advance where this will lead you: if you have an explosion, will you end up completely blackened in soot, or will you have created gold? In the process of collaboration you work very closely and this can create tensions and those tensions can be very good to push each other further, to stimulate the relationship, but it can also end up in disaster. This hasn’t happened to me yet, but it is possible.

As for the risk within the work, when you collaborate you create within a bubble of perception and you can live in a kind of illusion. Sometimes it is only when you have a real audience that you realize what you have been making. So it’s very useful to have small viewings and to have other people come in and listen or see the work in progress, because when you work closely together it’s very possible to be misled as well. But I think that’s exciting too; it’s exciting to create this kind of new world even if it only lives for a short while.

Avasilichioaei: What is your take on the sound poetry scene in Europe? What are some of the concerns or stakes for those artists currently working within this area?

Jantar: I find it very difficult to answer this question because I think it is very hard to grasp the sound poetry scene in total. It feels very diverse and while there is an international element, there are also many local colors; for instance, the French scene is very much based on text itself, there is also a Spanish scene that is based more on the performance, and the German scene would be very intellectual. I’m oversimplifying here but it’s interesting how language, once again, does kind of dictate the style of the sound poetry that you are in.

Avasilichioaei: Well then can you talk about the sound poetry scene in Belgium? Or to put it another way, if you were to think of yourself as being a node in a rhizome of polypoetic artists, who or what are some of the other rhyzomatic strands you feel most engaged with at this time and what engages you about them?

Jantar: As far as the sound poetic scene in Belgium, there isn’t really one. Because of the creation of Krikri there are a lot of poets who have started breaking open the text a bit more, but they don’t really go into what could be called sound poetry. However, there is a new generation of poets who try to incorporate the element of sound or the oral tradition in their poetry: Philip Meersman, Xavier Roelens, Olaf Risee.

As for poets with whom I feel connected, I would definitely link to Jaap Blonk, who works extensively with voice and has recorded and performed the Ursonate by Kurt Schwiters. This is a tradition that I feel very connected to because he also goes back to the classics and explores what the voice can do. David Moss would be someone as well who goes into extensive vocal techniques and expressive use of voice, as does Maja Ratkje, whom I respect a lot as a composer and as a performer and who adds electronics to the mix of voice.

Avasilichioaei: What are some of the projects you are currently working on?

Jantar: One is my first CD release, a compilation of pieces I have made over the last few years that will come out in Hybriden Verlag in Berlin. There are two performances that I am trying to create. One is called “weiß” (white), an exploration of white in different forms: a performance element, an installation element, as well as a book publication. The second is a performance with glass domes suspended in space. I want to create an installation that makes the whole space vibrate and be filled with sound. In using all the different pitches of the glass it is possible to create a room of sound, something quite physical. And I would like to make a performance with this installation: one person in a room filled with suspended glass domes, telling a text or story, one person interacting with this space and the audience would be lying on the floor or walking around. I will also continue collaborating intensively with angela rawlings, Ewout d’Hoore, Vincent Tholomé and Sebastien Dicenaire.

1. Kirkjubæjarklaustur is the name of a small town in southern Iceland. This is a compound of three Icelandic words, translated into English as church, town or farm, and monastery. In this form, a rough translation could be the monastery (klaustur) that belongs to the town (bær) that is governed by the church (kirkja). In other words, the church’s (kirkju) town’s (bæjar) monastery (klaustur). Lore has it that the first person to live in this town was a Christian. Wikipedia talks about the town here.

Edited by a.rawlings