Jump

Note: Photograph is from the collaborative project Cuerpo del Poema, by Irizelma Robles and ADÁL.

Translations by Urayoán Noel, like his poetry and criticism, are deeply enjoyable. They announce the presence of a vital mind – insightful, singular and often funny. Poems bound, spitting energy. The best part is that even at their most frenetic, the writings emerge out of a long, patient, and illuminating investigation into cultural forms and traditions.

Our conversation follows.

KD: Punk translator. I imagine it as a partner to the poetry-geek persona you adopt in performances. For example, the punk comes out in the anti-establishment gusto with which you argue for the horror – and attendant fascination – of certain works. Pablo de Rokha is one of these poets with the capacity to be “awesomely bad” who becomes great, erratically so, in your rendition. How does your identity as a critic play into your ability to conceptualize a punk stance for writers, and to translate & talk about the joys of awesome badness?

UN: It's hard to call oneself a “punk” anything when one teaches for a living and is photographed doing jump kicks à la David Lee Roth. Still, I also have a performance background (working with musicians, reading at and later writing about the Nuyorican Poets Cafe), and so I'm fascinated by the incompleteness of poetry, its multiple lives across page and stage, and I'm drawn to poets whose work feels somehow uncontained, irreducible to any one experience of poetry.

Poets as diverse and as geographically dispersed as de Rokha, Stein, Pedro Pietri, and Ana Cristina César all interest me along these lines: their work is willing to be what would be considered ugly or uneven or formless in an effort to embody language in complex ways. A lot of contemporary U.S. poetry is good at what it does (whether old-school-lyric, neo-formalist, experimental or whatever), it manages its own libidinal economy. But what I like about these other poets is their unmanaged energy.

Sure, de Rokha's poems get covered by punk bands in Chile, but I'm also thinking about punk as the freedom (of course relative to and bound by one's privilege) to be all over the place, to work outside the poetry silos, so that a comparatively “quiet” poet such as César, who's typically read in confessional terms, also fits. Neruda was a much more elegant poet than de Rokha, with his love lyrics over here and his surrealism and his social epics over there, but I'm haunted by these other poetics of totalizing messiness.

A number of these poets were also renegades within their respective national literary traditions, so I'm interested in mapping their eccentric poetic geographies, as I did with Pietri and Nuyorican poetry in my critical study. The critical work is partly a way of configuring a poetic counter-archive (across languages, cultures, and forms) that can guide me in my creative explorations.

KD: The uncontainability you describe is invigorating. You always make me want to read and do more. Another unfinished conversation we’ve begun in the past is about performance as a channel, or perhaps a form, for translation. What is your experience with that possibility? Your most ideal vision for it?

UN: For years now I've been thinking of my work across and along a “performalist” continuum where form and embodied politics blur and bleed through. You mention joy; a lot of the contemporary poets that inspire me (say, Edwin Torres or LaTasha N. Nevada Diggs) allow for a cultural politics of play that ends up being dead-serious.

Given my bilingual upbringing in the non-state of Puerto Rico, I'm especially interested in translingual poetries that “irritate the state” (to use a phrase from Doris Sommer's book Bilingual Aesthetics). As those translingual explorations have become even more important to my work (e.g. my forthcoming book Buzzing Hemisphere / Rumor Hemisférico), the border between translation, performance, and poetry has become increasingly porous.

One of the reasons I find Haroldo de Campos's concept/practice of “transcreation” so valuable is precisely because it foregrounds the ideological dimension of translation while still allowing us to understand it as a creative act, as a performance. In exploring app-assisted and/or homophonic translation that relies on my rereading or rewriting of my own or others' texts (as I do in Buzzing Hemisphere and have done elsewhere), I'm partly wondering what kind of embodied politics can survive the age of GoogleTranslate.

In performance studies, it's tempting to think of the body as THE space of political contestation and resistance, but of course our bodies and our critical awareness of them are messily enmeshed with technologies of power and in a sense only fully “translatable” in and through their remediations. In that sense, we are what Daniel Borzutzky calls “data bodies” and translation operates not only across languages but also across media and across cultures and geographies.

My “living in Spanglish” (to quote Ed Morales) also involves an engagement with what Emily Apter calls “Netlish,” a language defined by the tension between its awareness of its status as a cross-media experiment and its dream of universal translatability.

KD: We’ve talked over the years about your long-term interest in a “vanguard” poetics, drawn out of the term “vanguardia.” That term can be understood not only within the boundaries of a “conceptual poetry,” or aesthetic experimentation, but also as a poetics grounded in political concept. What have you wanted, and do you want, from a vanguard? How have those desires motivated you to take up translation?

UN: I don't think I have an existential investment in the avant-garde, with all its militaristic and largely Anglo-Euro male resonances, but as a poet-critic trained in Latin American studies I need a vanguardia, if only as a heuristic tool and a historical marker that lets me read texts as diverse and powerful as César Vallejo's Trilce (1922) and Gabriela Mistral's Tala (1938) in a specific transnational poetic context.

There's no easy way to translate that vanguardia into the modernist U.S. context, even though as Octavio Paz notes in his classic Children of the Mire, there are significant similarities and points of contact.

As I see it, one problem is that self-avowed avant-garde poetics in the present-day U.S. tends to align itself with and/or get read through the art world (e.g. conceptualism), so we end up with a lot of recycled gestures and old-school debates from that world (narrow takes on appropriation and representation, oblique riffs on institutional critique etc.) that sometimes seem like parodies of the social struggles of 2015, disconnected from broader poetic histories and practices, reproducing instead a kind of whitewashed art-world formalism.

I'm not saying that the politics of vanguardia are any less contentious than those of the avant-garde, only that they're a bit more capacious from my vantage point; I'm thinking, for example of Trilce and Tala as vanguardista texts that are also informed by a radically indigenous sensibility (even if they're often not read that way), as are various works of Brazilian modernismo. Can you imagine how different recent U.S. poetryland debates might have been if we had a way of talking about race/ethnicity and the avant-garde the way Trilce and Tala (and various de Rokha works, I should add) let us consider the possibility of an indigenous vanguardia?

I've always loved Lorenzo Thomas's Extraordinary Measures: Afrocentric Modernism and 20th-Century American Poetry partly because it fleshes out an alternative modernism that both complements and subverts the Anglo-American one, and in that way it allows for a poetic counter-history. As a critic, I can't help but care about these poetic genealogies, about their promise and their problems, and as a translator, I'm fascinated by how vanguardia and avant-garde function as false cognates. Mistranslation has its own energies, synergies, and genealogies.

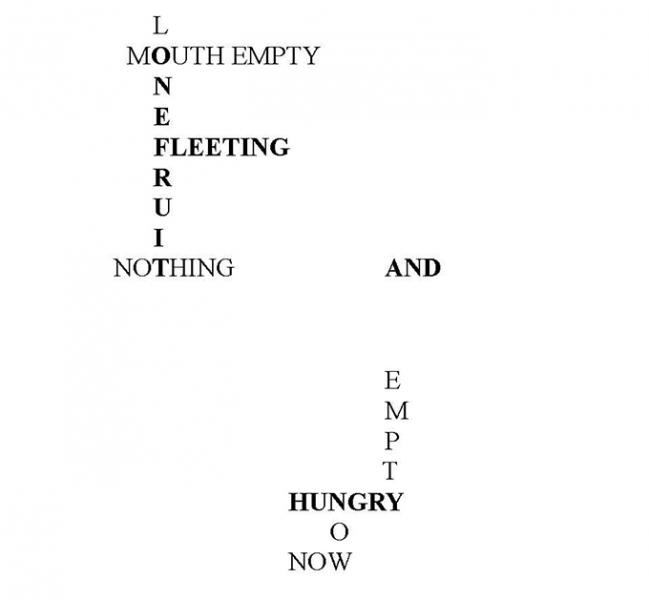

KD: You recently translated poems by Amanda Berenguer that play off concrete poetry traditions as well as concept. Some were originally published in her 1976 collection, Composición de Lugar (1976), while others ran in magazines. Here I’m including the first and third pages from her sequentially unfolding poem, “Sea-sunset from Saturday 26 February 1972.” What questions and observations occurred to you during the translation process?

[The important visual alignment on the lower segment is imperfect coming from my hands; a properly formatted version will be printed by Ugly Duckling Presse.]

Sea-sunset from Saturday 26 February 1972

A lone fleeting fruit

disproportionate.

Nobody reaches her.

She is swallowed skillfully

by the horizon.

Space is a mouth

stained with blood

now empty.

And we are hungry.

[. . . ]

Complete poem forthcoming in Materia Prima, a bilingual anthology

of poetry by Amanda Berenguer, from Ugly Duckling Presse.

UN: I was struck by her tone and her mood. Berenguer's concrete poetry is far removed from the sleek, mid-century international modernism of the Brazilian concretistas (even though concretismo did not shy away from a political critique of modernity's import-export logic). Still, Berenguer's concrete works are often dark and violent in ways that illuminate the rise of the dictatorship in 1970s Uruguay.

Hunger is key in the poem included here, and it's clearly a personal-social-spiritual hunger. Let's not forget that concretismo is also, as Haroldo de Campos famously put it, “poesia em tempo de fome” (poetry in a time of hunger), even as it anticipated many of the moves of contemporary Anglo conceptualists (the move away from reading text, the turn toward visual art and institutional critique/complicity). In Berenguer's case, I was intrigued by the idea that the move toward concrete poetry was a way of saying what couldn't be said given censorship and persecution, of speaking truth to power in the context of dictatorship and Cold-war militarization while remaining strategically illegible.

As befits its title, Composición de Lugar seems to be about composing an alternative spatial politics in and against the spatial politics of an emerging neoliberal order that, as Borzutzky reminds us, operated largely through U.S.-backed dictatorships (see Operation Condor). It would be fascinating to compare what Berenguer is doing here to the meditation on the status of racialized and policed bodies in Claudia Rankine's Citizen, if only to reflect on how and why the conceptual and the avant-garde as institutionally visible in the U.S. mostly define themselves in opposition to such critical engagements.

KD: Reflecting on various interdisciplinary moments in the arts where translation is a sometime presence or mode: Your photograph for this page was taken by Adál Maldonado, and I’m thrilled to have his contribution. You’ve published scholarship referencing his artwork, which ranges in handling from more iconic and subdued imagery into different registers of the avant. What does it mean to you to become a subject of his photography?

UN: Adál's work is important to me on multiple levels. Along with Pietri, he invited me to read and encouraged me early on, and his work remains an essential reference. In my book on Nuyorican poetry I touch upon the experimental and even conceptual turn in Pietri's work in the 1970s, and Adál is in many ways the pioneer of that turn.

His “out-of-focus” take on the problematics of diasporic Puerto Rican representation in the El Puerto Rican Embassy website (a collaboration with Pietri) works as a series of conceptual jokes and as a brilliant meditation on deterritorialized Puerto Rican identity. Inspired by the Royal Chicano Air Force, Adál realized that the problem of Latina/o political representation is the problem of representation in art, or at least that the latter could illuminate the former through works that challenged the terms of visibility and representation. (If this sounds a bit academic, it's because I'm writing an article about it.)

At the same time, Adál's work is (like Pietri's) very funny in a profound way, and its promise of a potentially disruptive political humor, as dada as it is decolonial, is one that animates my own creative work.

It's a thrill to be photographed for his Cuerpo del Poema (a collaboration with poet Irizelma Robles) alongside so many wonderful poets spanning the island and the diaspora. It's also moving, because, as conceptually charged as Adál's work is, it's also building bridges and doing the crucial, old-school work of documenting histories and communities. It's making visible even as it questions what we see. I guess you could call it vanguardia.

Intermedium