Proto/types

Proto es principio y ‘previo,’ lo anterior al efecto, al typo, que es error y tejido, texto. Hacer protos es hacer poemas en proceso, el preámbulo de la conciencia que como robopoeta es cyborg. Crear prototipos es unir lo real con lo ideal, lo irreal con lo posible. En palabra y objeto poético, en texto y vértigo lírico. Todo y posibilidad.

[Proto is beginning and ‘preliminary,’ the thing preceding the effect, the typo, which is error and textile, text. Making protos is making poems in process, the preamble to the cyborg awareness of the robopoet. Creating prototypes is uniting the real with the ideal, the irreal with the potential. In word and poetic object, in text and lyric vertigo. The whole and possibility.]

--Tina Escaja, 2015

Based in Burlington, Vermont, Tina Escaja has been exploring languages associated with new media and technology in her writing for many years. Some past projects appeared under the name of her Alm@ Pérez, a riff on a character from Miguel de Unamuno's Niebla. In that novel, Augusto Pérez becomes conscious that he exists only as a fictional character. Escaja considers Alm@ Pérez to be her avatar.

The avatar signs off on part of Escaja's latest project, the Robopoems. To date Escaja has initiated seven Robopoems as primarily Spanish-language texts, artifacts that look and work like poems. Because she works with Spanish as her first and literary language, I created English-dominant translations of her artifacts. [1]

Eventually Escaja hopes to see all of the poems translated into prototypes, and then into functional three-dimensional robots, each with the capability to move while speaking its designated poem.

Robopoema 1 [Originating Spanish-language poem for Robot 1]

Habitad@ de códigos

Code

Coding

Circuits

Algoritmo que infiere

mi entidad

sin ponderar

situación o efecto

mera respuesta

a tu número y tecla, diodos, sintaxis digital

el Verbo que me in/forma

y proyecta

Robopoem I [+English-language translation for Robot 1 prototyping]

Inh@bited by ciphers

Code

Código

Circuits

Algorithm infers

my entity

without weighing

position or effect

pure response

to your number and keyboard, diode, digital syntax

the Word that un/informs and

designs me

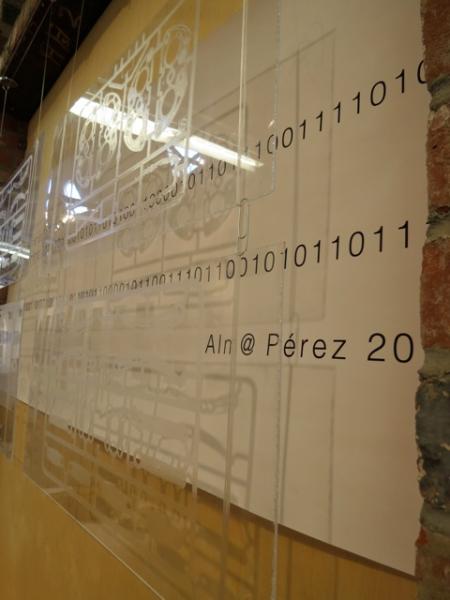

Another one of the seven segments of the Robopoem, VII, debuted in various modes in the setting of a South Burlington gallery, FlynnDog, in July 2015.[2]

The prototyped components of VII correspond to Escaja’s vision for spiderlike creatures that will not move smoothly or feature the latest slick cyberdesigns. Instead they will lurch around awkwardly. Their design, now in progress, incorporates non-robotlike materials such as the inappropriately organic material of wood. Escaja is launching Robopoems to front anxieties that crystallize around various binary oppositions in human relationships to robots, such as organic v. artificial, creator v. created, created v. creature, presence v. absence of intelligence, power v. powerlessness, and so on.

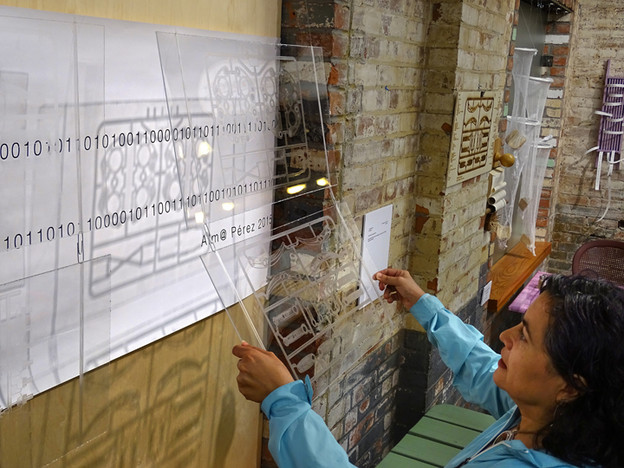

Poem-Robot VII will intone in biblical fashion: “A tu semejanza / mi Imagen” (“ According to your likeness / my Image”). The South Burlington show features some of Robot VII's body parts, its "protos." One item is a laser engraving on wood, which corresponds to one of the robot’s future legs. This version of the "proto"-leg is framed by all seven of the Robopoems in Spanish and English.

Other pieces displayed included four plexiglass panels engraved with Robot VII’s personal poem translated into binary code. Escaja positioned lights to shine through layers of the display, aiming to complicate the surface appearances of prototyped components with shadowy and residual effects.

Even as their body parts begin to materialize, the Robopoems will remain prototypes for some period of time as Escaja moves the project forward; that movement may be facilitated by a residency that has been awarded to Escaja by Burlington's Generator makerspace for September/October 2015.

My translations into English therefore function as components in the earlier moments of the robot project, as seen in the gallery display, surrounded by other kinds of translation through coding language and into three-dimensional existence. When the poem texts are recycled in their future robotics contexts, the Spanish-English linguistic balance within the prototypes may shift. Robotics engineers in Vermont are less likely to base design work on the Spanish-language texts than on the English translations, a point of which Escaja is already well aware. Despite this slide in weight, the Spanish Robopoems will still be programmed into the robots.

[1] In the larger context of Escaja’s work, as I have translated poems from a variety of projects, we decided to retain some Spanish-English switches. Flashes of bilingualism are relevant to the poet’s lived experience in Vermont. Because Vermont is an extremely low-density Latin@ state, however, Escaja’s bilingualism does not emerge out of residence within a large community of fellow bilingual or Spanish-dominant speakers. Therefore in my occasional use of Spanish in the translations, I have taken Escaja’s individual reflections and preferences on language into account, rather than attempting to project codeswitching patterns recognizable to other bilingual people. A related point: in the original Spanish of her opening quotation, Escaja decided to spell "cyborg" in English because she feels that's how she relates to this term, even though the Real Academia offers an alternate spelling for Spanish.

[2] The exhibition, “Works Both Ways,” was curated by Sharon Webster.

Intermedium