Quick now

Angel Escobar’s awareness of motion is one of the many elements that make his poems undeniably powerful. To me, as I translate his poems, there is no doubt that Escobar (1957-1997) created multivalent, energetic work, and that a quick reading of one or two poems at least hints at his range. Other writers, at the very least other poets, must recognize the surety of his movements.

Then in moments of pause I wonder about whether the quickness of published pieces – those introductory yet central experiences of encounter with loose poems here and there, or a translator’s commentary in a journal – truly gets so much sensation across. The quickness of Escobar’s mind and life are out there, in his writing. Will readers find them?

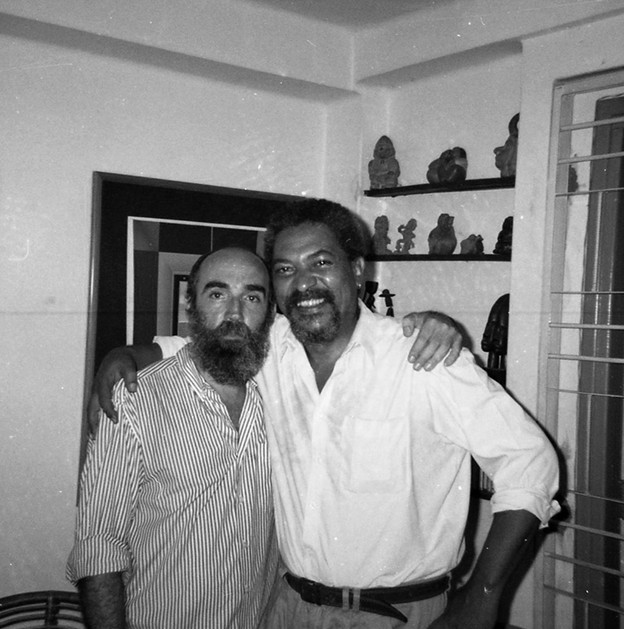

Beyond the bounds of the poems themselves come the contexts, offering guidance to new readers. Angel Escobar’s widow, Ana María Jiménez, has pointed out that existing Spanish-language commentaries around his life and death tend to flatten his representation in their repetitions of certain themes.[1] For example, these themes don't tend to include the happiness we see in the 1987 photograph above.

It’s a good reminder to translators – and in parallel fashion, scholars writing critical studies – to periodically pause and take the measure of all these things we create. Our renditions of literature and their paratexts (all those ubiquitous bio notes, plus the commentaries, blurbs, translations of essays by other poets on the relevance of the person or work, the scholarship and so forth that serve as companions to literature) travel in fragmented forms through the worlds of publishing. Where these write-ups successfully pursue some theme with great determination, that very pattern of emphasis causes other possibilities to fade.

Below I ask Angel Escobar’s friend who appears in the photo above, artist Nelson Villalobo / Villalobos, to share reflections expanding on ideas that are available in English to date; I also reprint a poem in which Escobar draws on their friendship. In the picture above, the friends appear in Nelson's home and studio in Havana, San Miguel del Padrón; and that setting seems quite relevant to the poem, "Collection / Colección."

Escobar’s book Abuso de confianza, or Breach of Trust, is forthcoming from the University of Alabama Press in 2016. Escobar has other strong books; I chose to bring this one into English first because of the impassioned recommendations I heard from many island poets with diverse approaches to writing. Breach of Trust delivers an existential, resistant NO!, paired with a fragile assertion of the right kind of yes, a balance deeply important to many readers of the Spanish. Meanwhile, commentators regularly comment on the painful and tragic strengths of this book in tandem with Escobar’s 1997 suicide. And so proceeds Escobar's canonization.

The pattern follows a powerful tradition in island poetry of linking literature with death, one that transcends the individual and speaks to a community. José Martí is the most famous precursor in this recirculating canon, so in a sense, it’s quite an honor for Escobar to be perceived and described within a similarly powerful cultural dynamic.

Escobar dialogues beautifully, and significantly, with the Cuban canon in Breach of Trust and other books. An extraordinary combination of literature and death is perfect for comprehending the appeal of his resistance through poetry: Escobar spans centuries and skewers the 20th century in particular, his own terrain in time, in Breach of Trust.

But even a kaleidoscopic appreciation of his NO can obscure dimensions of his yes that should not be lost, particularly if there's any hope of comprehending his poetry in relation to the everyday -- first the importance of how anyone gets through the mundane time in everyday life, and then the importance of a different everyday involving illness and Escobar's extended daily battles for survival. As a result, I think that his widow has a point.

A canon, in the end, is only a tool. A usable mythology enabling some useful conversations, regardless of how mystical and sacred the tool may come to seem. Moments arrive again and again for breaking away from it to pick up another tool, to speak to an audience with other priorities. Anita, Escobar's widow, has spoken of her sense that his need and love for music and art have been muted topics in the conversation emerging to date.

Villalobos, Escobar’s friend who presently lives and works in Spain, has kindly agreed to share a photograph and memory for this entry. Escobar refers to him in this poem invoking visual art and quickness in tandem with the existential meditation:

Collection

Rapid lines: pain, pardon; revelry, life.

Villalobo: longings for integration, a pinch of salt,

the sky black above, tautological blue, only uproar.

The pen, ink, and paper for compassionate improvisation

among tables and padlocks; cruel too, everything teems.

A reference appears, the jazz inquisitive, probing the unknown

portion of light. Contrite one returns, the hand, the eye, the feints,

style that self-parodies and seeks its own shelter.

Lam, Matisse, Picasso, Villalobo, the street—

an angel in a test tube, distant cities,

and the countryside, the branch that branches out,

escapes, conceals itself. We’ll see those figures again.

We’ve paused in our nostalgia for perfection.

Something lies ahead of us, faint – quick and mad;

everyone confines the fools, attempts sidewise

to make them positive; in the middle, cruel affliction.

The motifs have been observed. The light returns in silken lines.

You close your hand and see the gesture appear,

not furious, no, quiet and circumspect; you open your hand

and so everything comes to be: like the wave’s ludic mishap,

the line that knows disaster, that returns,

sparks with light and recollection, auscultates.

Colección

Líneas rápidas: dolor, perdón; jolgorio, vida.

Villalobo: ansias de integración, un poquito de sal,

el cielo arriba negro, azul tautológico, sólo una bulla.

El lápiz, la tinta y el papel para la improvisación tierna

entre mesas y candados; cruel también, todo se arremolina.

Aparece la cita, el jazz curioso, ese hurgar en lo desconocido

de la luz. Vuelve el contrito, la mano, el ojo, fintas,

estilo que se remeda y busca su cuidado.

Lam, Matisse, Picasso, Villalobo, la calle—

un ángel en una probeta, las ciudades lejanas,

y el campo, la rama que vuelve a ser la rama,

que se escapa, se esconde. Volveremos a ver esas figuras.

Nos hemos detenido en la nostalgia de perfección.

Algo nos aguarda, tenue –rápido y loco;

a los insensatos todos los encierran, buscan de lado

hacerlos positivos; en medio el quebranto cruel.

Ya se acataron los motivos. Vuelve la luz con sus caireles.

Usted cierra la mano y ve que aparece el ademán,

furioso no, callado y circunspecto; la abre

y se da todo así: lúdicro percance de la ola,

la línea que conoce el fiasco, que vuelve,

que enciende y rememora, ausculta.

Translated by Kristin Dykstra with the permission of Ana María Jiménez de Escobar (heirs of Ángel Escobar). Spanish originally published in Cuando salí de la Habana (1996). This poem and an earlier version of its translation appeared in a dossier dedicated to Escobar in Sirena: Poesía, arte y crítica in 2010.

For a time I wasn’t sure why Escobar dropped the “s” at the end of his friend’s surname in this and other writings. It’s the the kind of minor detail that I mentally red flag – a misinterpretation at this level can lead to errors of thematic association, and then to escalating errors in the notes or essays I might write about the poem and more. This absence of the “s” didn’t seem to be a mere typo, since Escobar repeated it in various places.

Now Villalobos has clarified that this poem does mark an explicit dialogue with his art. The lack of the “s” is a variant in the family name that goes back to his own father’s generation, and perhaps before. Here he segues from that explanation into remarks on the merging of poetry with art, poet with artist:

The missing "s" in Angel’s poems is no typo. In my artwork, and as an artist, I use a signature without the “s.” I myself only realized that my surname has an “s” when I arrived in Spain. Everyone in Cuba called me Villalobo and still does, so that’s how I’m named in my country. It was my father’s error when he recorded our names, because he too used the last name without the “s,” and I think that came from even earlier. Haha. But anyway it has always been that way in my artistic signature; in my work I’m Villalobo, and this Villalobo created the Villalobismo to which Angel refers in the last poem he wrote and left in the typewriter before his suicide, it’s dedicated to me, a small and at the same time great biography of me and my work and of Angel himself. We would always say that our work was that of a single artist, that I was the painter he was not, and he was the poet I was not. [email 3 October 2015, my translation]

La "s" que falta en los poemas de Ángel no es una errata, yo en mi obra y como artista firmo sin la "s". yo incluso me enteré de que mi apellido tenía "s" cuando llegué a españa. Todo el mundo en Cuba me llamó y me llama Villalobo, y así es como estoy inscrito en mi país. Fue un error de mi padre al inscribirnos porque él también tenía el apellido sin la "s" y me parece que incluso venía de más atrás. jaja Pero de todas maneras ya se ha convertido desde siempre en mi firma artística, yo en mi obra soy Villalobo y este Villalobo ha creado el Villalobismo al que se refiere Ángel en su último poema que escribió y dejó en su máquina de escribir antes de suicidarse que está dedicado a mi, que es una pequeña y a la vez gran biografía de mi y mi obra y del propio Ángel. Nosotros siempre nos decíamos que nuestra obra era la de un solo artista, que yo era el pintor que el no era y que él era el poeta que yo no era. [correo 3 de octubre 2015]

I asked Nelson what artwork the poem "Collection / Colección" brings to mind for him, with its emphasis on ¨rapid lines.¨ He sent me several images, among them this one:

To see more about Villalobo/s online, you can go to his own site or to pages maintained by family: the Villalobos Cine site, maintained by Nelson's son Pablo, or here to "Todo se moja menos la lluvia" (Nelson's daughter Daisy Villalobos Leal is also a poet, who remarked over email that Escobar is a major influence).

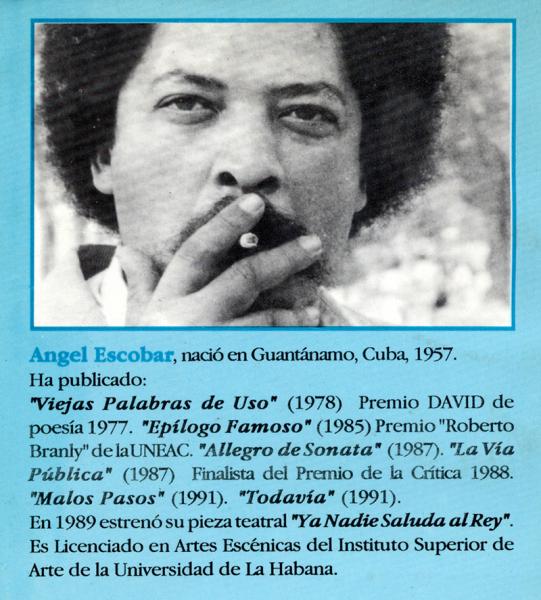

Lastly, Villalobo/s is the photographer who took this shot of Escobar, which appeared on the back of the original edition of Abuso de confianza. The book was published in Chile prior to its republication in Cuba.

[1] Jiménez has expressed concerns directly to me in the past, as we discussed permissions and translations. Juliet Lynd also interviewed Ms. Jiménez in Chile and wrote this excellent article about their conversation, touching on the dilemmas that occupy me here. See “Reflections on a Conversation with Ana María Jiménez, Wife of Ángel Escobar,” in Sirena: Poesía, arte y crítica 2010:2 (126-136).

Intermedium