'Black W/Holes: A History of Brief Time,' part 1 of 2

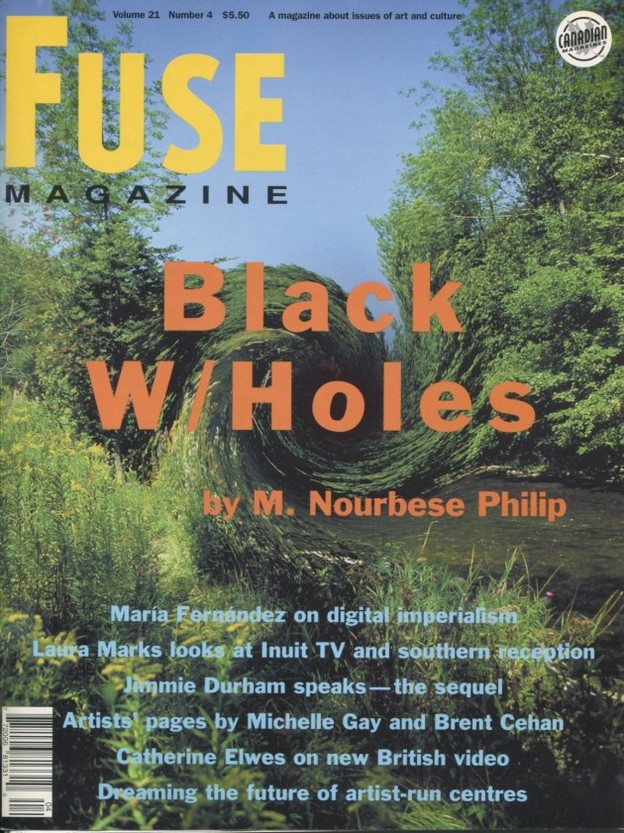

What follows is Part 1 of 2 of M. NourbeSe Philip’s essay, “Black W/Holes: A History Of Brief Time,” which combines definitions from Stephen Hawking’s A Brief History of Time with an urgent discussion about race relations in Canada and beyond in the late 1990s. This essay was originally published in Toronto’s FUSE Magazine in 1998. After sending Philip my commentary, “Physics of the Impossible,” which speculatively discusses her book-length poem Zong! (Wesleyan University Press, 2008) in relation to Albert Einstein’s theories of relativity, she sent me this essay. Since it only appears in the back issue of FUSE, I am presenting it here with her permission.

Part 2 of 2 can be found here.

***

Black W/Holes: A History Of Brief Time (1998)

By M. NourbeSe Philip

Part 1 of 2

event: A point in space-time, specified by its time and place.

Immersed in a recently bought newspaper, I exit a variety store and almost collide with a man walking west along St. Clair Ave West. I am immediately apologetic. His response is swift. And contemptuous. “You fucking people are all over the place!”

I suggest he do something to himself which is anatomically impossible I am angry—very angry. I am also afraid. He is white. He is male. In a big city interactions like these can easily become fatal. I quickly duck into a another store. Some minutes later I emerge and am relieved to see his figure a block or so ahead of me.

Quark: A (charged) elementary particle that feels the strong force.

“You fucking people are all over the place!” The white man’s words remain with me for a long time. They reverberate within—“all over the place...,” “all over the place...” If nothing else, it was clear that he felt I ought not to be on St. Clair Avenue West. The further implication of his statement was that my being on that street in Toronto was evidence that we—African people, I suppose—were “all over the place.” The corollary being that we ought not to be. I could easily dismiss that man’s statement, were it not for the fact that the notion of illegitimacy contained in his words is carefully nourished, cultivated and brought to splendid fruition in the white-supremacist immigration practices of all the western, so-called democracies. The main job of these countries—formerly the Group of Seven, now the Club of Eight—appears to be figuring out how best to club the rest of the world into submission, while keeping darker-skinned peoples physically corralled. Meantime capital, which is in fact our capital, wielded by multinationals, runs rampant and rough-shod all over the world. Indeed, all over the place!

big Bang: The singularity at the beginning of the universe

for five hundred years the essence of being black is that you can be transported. anywhere. anytime. anyhow. for five hundred years a black skin is a passport. to a lifetime of slavery. a guarantee that the european can carry out terrorist acts against the african with impunity. for five hundred years the european moves the african “all over the place.” at his behest and whim. and then one bright summer's morning, he looks me in the eye and tells me: “you fucking people are all over the place.”

ever since the holds of the slave ship, the european attempts to curtail the every moving of the african:

the moving in time

the moving in space

the moving into their own spirituality

the european forbids the african language; forbids her her spirituality; forbids her her gods; forbids her her singing and drumming; forbids her the natural impulse to cling to mother, father, child, sister and brother—forbids her family. leaves her no space. but that of the body. and the mind. which in any event they deny. cut off from their own histories and History, the african moves into a history that both deracinates and imprisons her. in the primitive. in the ever-living present absent a past or a future.

uncertainty principle: One can never be exactly sure of both the position and the velocity of a particle; the more accurately one knows the one, the less accurately one can know the other.

I live in a starter home. On a starter street. For two decades I have lived in a starter home. The street remains a starter street for many who buy their first home there—a starter home—then move on. There are a few like me and my family, however, who defy the very meaning of start which intends always to lead to somewhere else. We remain. Stay put. In a starter home. Away from home. Defying the wanderer, the lost, the unbelonging in Black. The spore at the root of Africa.

today—the black skin is not so much a passport as an active signifier to those manning borders of the brave new world order of everything that must not be allowed in. crime, drugs, AIDS, sex, ebola,... into these self same western democracies whose spawn—the metastasizing multinational—is all over the place.

Robina, Winona, Alberta. Three women's names. And the names of three streets in the neighbourhood in which I live. The same one with the starter home. The story is that at one time—in the past—is there such a thing?—a Black man owned the land on which these streets are now located. That man had three daughters whose names were Robina, Winona and Alberta. I have never verified this story, maybe fearing its inaccuracy. Somehow I feel more connected to this area, knowing? believing? that a long time ago Robina (I had an aunt called Rubina), Winona and Alberta, three Black women, grew up here. In this neighbourhood. And that their father once owned this land.

Which in turn begs the question. How did he own it? How do you, as a blackman—an African man, or woman ‘own’ land in a space e/raced of its native peoples, bounded “from sea to shining sea” by the ligaments of white supremacy? A space. Our home and native land—our stolen, native land. A space. Still being warred over by the descendants of two European powers. How do you own land, a house, even a starter home in a space and place where a minor encounter with an/other gives rise to the challenge of your legitimacy in this space. A space of massive interruptions. And disruptions. Mostly fatal for the First Nations people. That is the new world. That is the space we call canada.

magnetic field: The field responsible for magnetic forces, now incorporated, along with the electric field, into the electromagnetic field.

Goethe was of the view that the negative space around which leaves develop influenced the shape of a plant as much as their genes. Something in the surrounding emptiness, he believed, gave shape to the leaf.

What is the space—the negative space—that is Canada, around which I grow? Around which African people—Black people—grow. How does that negative space shape us? And do we, in turn, shape that space—moulding it to fit our specificities?

in this space we call canada, blackness serves as a cypher. a tool. the means by which the larger, white space shapes and ritually purifies itself. blackness becomes the most effective way in which the essence of canadianness—is there such a thing?—is articulated and the purity of canadian space is ensured. so that the refrain—“you fucking people are all over the place” is modified—parsed into “you people will not be allowed to be all over this place called canada. except and in so far as we allow you to be.”

spin: An internal property of elementary particles, related to, but not identical to, the everyday concept of spin.

Time and again in the media, the involvement of African men and women in crime becomes the excuse to question the effectiveness of the immigration act. As if white men and women do not commit crimes. As if the very space that is canada is not founded on profound and unforgivable crimes against First Nations people. Against humanity.

“Why are we letting these kinds of people into our country?” the editorials question. Deportation becomes the most favoured tool to deal with that speciality, “black crime.” Despite the fact that many, if not most, of these people convicted of crimes may have spent their most formative years here. in this space called canada.

At least once a year white Canadians ritually define and purify themselves and their space by going through this public process—ably assisted by their media handmaidens—of ensuring that indeed “you fucking people are not all over the place.

Every two or three years these rituals culminate in the high mass of a commission of inquiry into the state of immigration. The recommendations of these commissions invariably narrow the manoeuvrable space allowed Africans and other peoples of colour. Head taxes, extended waiting periods for refugees, genetic testing of family members—the list of punishments for those who have sinned by desiring to enter the space called canada is long and exquisitely tortuous.

1973 was just such a year: Canadians would examine how immigration practices were affecting the country. In a country built primarily on white immigration, it is significant that in the 1974 Green Paper on Immigration, all the worst case scenarios used examples of African peoples: for instance, how would parents feels about the “fate of their offspring if their children were to marry a black person.” All material showing the potential effect of demographic changes resulting from immigration used examples of domestic migrations of Black Americans within the United States—a country convulsing in response to challenges to its governing ideology of white supremacy. The black body becomes the measurement—the point at which absolute difference is established.

acceleration: The rate at which the speed of an object is changing.

an emptiness—an absence

shapes me shaping it

as the space around

the leaf serrates

the oak

fringes the willow

needles the larch

you may be born here—your mother’s mother and father’s father—you will still get asked where you’re from. if your skin is black. you answer here. which is where? but if the minister of immigration gets her way—even being born here, in the space called canada, will be no guarantee that you can claim Canadian citizenship.

the white that is snow

shapes itself around the silence

of cree and ojibwa—a hardness

in the face of something new

strange

primordial black hole: A black hole created in the very early universe.

“all over the place!” is there anywhere in this world—this brave and newly ordered world—to which a white skin does not become an automatic passport? all over the place, indeed! from the fifteenth century on, columbus, pizarro, hawkins, drake and others of that ilk—robber barons all supported by their robber—baron monarchs—run around the world terrorising africans and other peoples of colour. this is how they repay the hospitality of their hosts wherever they land. their most effective weapon is the company. there is a plethora of companies: the dutch east india company, the company of royal adventurers, the french east india company, the royal african company and on and on. and they deal in bodies. black bodies. what they call pieces of black ivory. today the ceo sons of these same robber barons and buccaneers sit atop multinational corporations whose work has not changed in five hundred years. they still deal in bodies. yours and mine. “you fucking people are all over the place!” talk about role reversal and projection.

Take the Ossington bus north—say at Dundas. Ride north on it to Eglinton. Observe how the bus goes through a chromatic shift from light to dark as you enter the space of Blackness. That ‘exotic’ space of Blackness as rendered by Atom Egoyam. Up on Eglinton. Heartland of exotica. Exotic from whose perspective? (No review or critique of this film challenges the use of Blackness as nothing more than a signifier. For the exotic.) Then take a walk down Bay. Not so much heartland as engine of the capitalist machine. Observe how monochromatic that space is. Its beat that of a metronome.

rhythm is simply space divided by time. “up on eglinton” at oakwood is rhythmed in the same time as port of spain, trinidad; as accra, ghana; as scarborough, tobago; as kingston, jamaica; as harlem, new york.

event horizon: The boundary of a black hole

Canada is the clichéd land of wilderness. Like all clichés it is also founded on truth—the space that is canada contains 20% of the world’s wilderness. And yet in such vastness Africans and other peoples of colour are to be found by and large only in urban areas. Forty minutes outside of Toronto African peoples are invisible. Not present. Despite some four hundred years on this continent—in this land called canada. Cottage country remains a white enterprise in every sense of that word. Complete with power boats, jet skis and luxury cottages. It is, indeed, a strange way to be “all over the place” when African and other children of colour are noticeably absent from “wilderness” camps outside of the urban areas.

What is it about this experience of “wilderness”—this very Canadian experience—which Africans and other peoples of colour who have come here as immigrants do not participate in. Do our African brothers and sisters who have been here far longer than we fresh water Canadians have, engage in a different relationship with this twenty percent wilderness?

There appears to be some sort of psychic border which prohibits or limits our entry, as “Others,” into this particularly Canadian aspect of life. Considering that most immigrants are at most one generation away from the land, their lack of engagement with it in Canada is significant. For many peoples from Africa and Asia, the land remains integrally linked to their life: not only is it the source of food, but also of healing and spirituality. With European settlement in Canada, however, the “wilderness” has developed a language which we cannot penetrate, unless we enter the world of whiteness—possess a cottage and boat. With the e/racing of the First Nations presence and their removal to reservations, their wisdoms, their languages, their manner of relating to the land have all been unavailable to us. The “wilderness” has indeed been racialized.

Safety lies in numbers. This is why we African peoples coalesce in cities. We know we will find others like ourselves there, we will find foods we’re used to. We can hear our languages spoken. There is an immediate sense of connectedness which cannot be underestimated. It recreates the illusion of home and belonging.

imaginary time: Time measure using imaginary numbers.

I am a child, sitting in a darkened movie theatre. This is our regular Saturday treat. A matinee. The cowboys and white settlers are on the lookout for Indians. The beautiful scenic river becomes ominous: Indian savages may be hiding in the bushes just waiting to scalp white men, women and children. Several years later I paddle a canoe along a quiet lake in north Ontario, round a bend and for a split second am afraid, expecting a canoe of tomahawk—brandishing Indians. Maybe Tarzan will come and rescue me.

Long before I am aware of it the “wilderness” is racialized. In movies, books—fiction and non-fiction, and comic books. I am not from the American South, but as an African person the American South is in my psyche. Somewhere.

Walking up a back road in Southwestern Ontario the sound of an engine behind me tenses my body; my thoughts—and fears—turn to rape, lynching and racist rednecks. Nor can I forget, while vacationing in Minden, Ontario, deep in the Haliburton Highlands, that white supremacists held a rally in that very town not that long before.

When you put an African person in the woods, in the “wilderness”, one of the first images that comes to mind is that of being hunted. By dogs. By white men with shotguns.

The immediate and individual power of the redneck cannot be underestimated—one only has to think of the recent lynching in Texas of an African American by three white men who tied his body to a truck and dragged him to his death. As the most powerful purveyor of popular culture, however, the movies have played a significant role in representing the “wilderness” and rural areas as the heartland of the redneck. They also let the urban redneck off the hook. One of the strongest screen images of the ur-racist is that of poor, white trash riding shotgun in an old beat—up pickup truck. Seldom do we ever see those three—pieced, pinstriped business men and women (members of the Club of Eight) riding shotgun, hunting Black people. But they are, indeed, the ones with the resources and commitment to the policies and practices which have carefully nurtured and sustained the belief system of white supremacy.

Meantime Africans are literally scared off the land, which the European purchases and enjoys relatively free of any contact with African people.

It is winter. I am standing on a frozen lake some two hours north of Toronto. There is a still whiteness all around me. In this moment I recognize something about the way in which First Nations people relate to the land. As a living, breathing force which one needs to interact with. Not to conquer, but to be in relationship with. Several hours later I hear the First Nations scholar, Georges Sioui, speaking eloquently about the need for the newcomer—the european—to learn the concept of Americity. Americity, he argues, encapsulates an approach to the land which all the first peoples of the Americas share.

Note: All definitions appear in Stephen Hawking’s A Brief History of Time.

Quantum poetics