The infinity in language

“Poiesis, in the deepest sense, is cosmology.” —Adam Cornford

In addition to poets using science as a source for metaphor, claiming science as a type of poetry, and conducting science as poetry, there are poets who are making science a determining element of their worldview. One such poet, Adam Cornford, whose poetry and critical works intersect with evolutionary biology, physics, cosmology, and more, and who Andrew Joron has called a “cosmo-surrealist,” has said in our recent conversations that his aim is to discursively imagine science as a way to “(re)imagine that which we know, especially that which we know indirectly, that is, by way of instrumentalities and mathematical schemata.”Like scientists detecting a planet not ordinarily visible by measuring a nearby wobbling star, poets commonly access indirect knowledge, but Cornford’s emphasis is unique in that he seeks these alternative forms of knowledge from questions specific to both poetry and science. As such, Cornford is the kind of poet who I see as crucial to extending transdisciplinary conversations by contending with ideas too often ignored by poets and scientists, ideas that can be addressed by way of both scientific and poetic reasoning.

Cornford works from this worldview not only in his writing but in his pedagogy, having taught courses on poetry and science in the Poetics Program at New College in San Francisco, courses that I see as precursors to the poetry and science course currently being co-taught by Rae Armantrout and Brian Keating at the University of California at San Diego.

Cornford’s lyric poems encompass not only scientific and rational modes but modes situated in Surrealism, mythology, mysticism, and Romanticism. The tension in his work finds ground between the real and surreal, rational inquiry and the imagination, waking experience and dream states, and the history of science and poetry as they relate to pragmatic and theoretical questions about reality and what he has called, in relation to the multiverse, “the infinity in language.” For Cornford, science and poetry “are metaphorical attempts to express the previously unperceived (or, in cases like gravitation or electrons, unperceivable directly) in terms of the perceived. But in poetry, the way in which the elements of the perceived are combined through language may itself create new ‘impossible’ entities that are nevertheless perceivable by what Blake calls the eye of imagination.”

Among Cornford’s literary works is a poem that invokes surrealist Leonora Carrington while operating like a topological Klein bottle, poems that investigate technologically mediated experience by working from Donna Harraway’s A Cyborg Manifesto, and a science fiction novel that provides a multiversal explanation of dark matter, conceived of as the gravity of other galactic-scale masses in the quantum multiverse. The following poem, from a recent manuscript, “LALIA,” shows the meeting of scientific inquiry, Greek mythology, and lyricism in his poetry:

Initial Singularity (for Samuel Delany)

Before even silence is uttered

Zeus is a point particle

Of infinite energy, infinite mass

Until his will’s widthless rod

Of lightning defines direction

And Aphrodite slides out of him,

Flat as her shield, endless as π

From her, then, ingenuity

Unfolds like a bronze rose

Whose petals razor the hand

In “Nowhere Wind Mask,” a new long poem, Cornford addresses the many-worlds theory in theoretical physics while investigating human consciousness and Planck time, which is how time is measured in quantum mechanics:

...the wind

between the worlds not

the wind that in dreams blows out of the hairline

fissure between our world and the adjoining world open at the horizon at the instant of sunset

not the wind

that brings questions our world has not known how to ask

like molecules of fragrances impossible to describe carried and drifted from the other shores

like regions that have fled over the light horizon beyond what we will ever observe

No this wind flows between this world

and this world

its nowhere in this world as it was a Planck time ago which is now

nowhere noworld only information carried forward on the wind to Mask

but its macrostate evolves slowly like an unfurling universe of smoke a wave function so vast

that all the waveforms of the whole planetary ocean over four billion years could not describe it

And so more masks are made:

In the afterword to his poem, “The Exquisite Corpse and the New Wine: A Theogeny,” a work that considers quantum uncertainty and evolutionary systems, he says that the poem is an address to the making of myth in a scientifically based culture:

…the poem, then, also like Blake’s later poetry, is an address to the problem of mythopoiesis, the making of myth, in a scientifically based culture in which truth, and therefore meaning, is contingent and approximate, not “eternal.” (Fundamentalisms are another, and profoundly wrong, kind of answer to this mythopoetic quest for cosmic meaning.) That said, my poetic goal, like Blake’s, is not to preach doctrine or system but to “rouse the faculties to act,” to engender new visions in the reader that surpass my own, and to open the gates of eternity in that reader as in myself.

In our discussions, Cornford has talked about reading George Steiner’s After Babel in which Steiner uses the concept of alterity to discuss the “Borgesian library of counterfactuals made possible by language” and how he misread the word “alterity” as “alternity,” “the infinite ensemble of the possible-real.” From that and his studies of the many-worlds theory, Cornford derived the word “plureality” to mean the ensemble of realities that form the multiverse, seeing poetry as an aspect of this ensemble. He writes:

We begin to understand that language itself, all the dense, branching interconnectedness of human sign-systems with their metaphors and metonymies, their subjunctives and conditionals, is a working model of Plureality. Yes. We mayfly-lived, mayfly-fragile, utterly fallible creatures in this backwater of happenstance are linked in the deep structure of our very brains and means of thought to the architecture of the Real.

This quality of Cornford’s thinking, to ricochet between the Blakean gates of eternity and the multiverse, making the architecture of the “Real” more variable than often imagined—like the surrealists as well as the physics of nearly a hundred years ago—represents an important branch of thinkers who are not only reimagining poetry and science by considering them in union but, in doing so, reconstituting reality itself.

* * *

To scale deeper into Adam Cornford’s thinking on poetry and science, see this excerpt from his essay, “Cosmology: Intelligence And Infinity In Language,” originally published in 1996 by the Toronto e-zine, The Alterran Poetry Assemblage:

A conundrum in contemporary cosmology is the fact that the universe we inhabit actually supports the organization of matter/energy into atoms, molecules, stars, planets, and finally, life—even intelligent, language-using life. Our universe supports this organization by virtue of quite specific and delicate balances of fundamental physical forces. The odds against winding up with such a universe following the Big Bang are very considerable. Far more likely, if the constants of the nuclear forces had emerged in only slightly different relation to one another in those first few hot fractions of a nanosecond, there would have been no universe—a collapse back into a spaceless, timeless, pinpoint of potential—or a completely entropic universe of dispersed subatomic particles spreading away from each other for ever. Or there might have been a universe whose highest level of organization was huge thin veils of dust and gas, or a great burst of black holes of various sizes cannoning out across expanding nothingness. In none of these universes would there be planets, especially not blue-green ones hosting viruses, plankton, palm trees, lightning bugs, larks, and philosophers.

Modern cosmology looks to quantum mechanics in attempting to resolve this conundrum. Specifically, explanations for the existence of an improbable, intelligence-generating universe center on interpretations of a core issue in quantum physics, the “quantum wave function.” The wave function describes the probabilities that a given subatomic particle (quantum), whose origin is known, will behave in one way or another when observed at a later point in time and space. Once the observation takes places the wave function is said to “collapse,” because out of all the probabilities, only one is “real” in the sense that it has been observed. The standard (Copenhagen) interpretation of the quantum wave function is that the particle’s “actual” behavior does not become real until it is observed and the wave function collapses; until that instant, all that is “real” is the wave function, the mathematical set of probabilities. The observer makes the specific quantum event real by observing it.

In keeping with this notorious but widely accepted bit of weirdness, one school of thought attempts to resolve the improbable-universe conundrum by proposing that the improbable universe we inhabit exists precisely because we are here to observe it. This a version of what is called the Anthropic (human-centered) Principle. Another, somewhat less popular view, the “many worlds” or Everett interpretation of the quantum wave function, says that all the universes possible at any given moment actually exist, some parallel to one another, others branching in and out of each other as quantum events occur—as wave functions collapse one way in one universe and another in another. Many of these universes, of course, have only infinitesimally brief existences, since they differ from their nearest “sister” universe only by one quantum’s-worth, and may simply become identical with this sister again in the next instant. But other “sisters” branch away, becoming more and more different from the “mother”; and still others branch away from these in turn. By this interpretation the continuity of “our” universe is no more real than that of a film, in which apparent continuous movement is produced by the rapid succession of individual still images, each differing only slightly from the ones preceding and following it. Just so, we “surf” the continual appearance, divergence, and disappearance of timelines, in others of which different events happened than the ones we remember, and in still others of which we (or our parents, or our culture, or life on earth) died in the next moment or never existed at all. We are, according to this theory, surrounded by an infinity of universes, all originating in the Big Bang—and in most of which, according to the laws of probability, nothing of any great coherence or interest exists.

I suspect that the same is true of the infinity of language. The possibilities are, in a mathematical sense, limitless; but most of them are pretty dead. It’s quite easy to write a software program to compose sentences, building from a dictionary and sets of grammatical rules. But even if the dictionary has attractive and resonant words in it, even if one programs in a few tropes—simile, alliteration, anaphora, assonance and rhyme—the result gets quite monotonous after a while. Occasional lines gleam with vivid meaning or mysterious beauty like fool’s gold in a stream, but they become genuinely meaningful or beautiful only when lifted out of the flow of routine-generated sentences and linked to some human context—when “observed.” We don’t need the chimps with typewriters now—computers can do the random “typing” a lot faster—but it would still take an awful lot of very powerful processors a very long time, using the most scholarly programming based on Shakespeare’s stylistic and narrative repertoire, to compose anything even remotely as good as the most mediocre Jacobean play. And randomly, it would still take forever.

The astute reader will object at this point that the analogy breaks down because language is a human artifact. That is, unlike the potential range of relations of physical constants in possible (or parallel) universes, all the elements of language are parts of a semiotic system and always have some meaning in relation to one another, even if only in the faintest connotative way. When Chomsky, famously, proposed the sentence “Colorless green ideas sleep furiously” as an example of the way grammatical rules can generate “meaningless” sentences, poets took this as a challenge and based poems on it. (Arguably, it was the very strenuousness of Chomsky’s evident effort to be meaningless that made the sentence interesting, because he gave it at least two oxymorons—“colorless green” and “sleep furiously”—that are suggestive to the poetic mind. As a theoretical grammarian, Chomsky lacks a good grasp of connotative processes, which are not grammatical. For really low levels of meaning, try mid-level butt-covering bureaucratese or sub-Lacanian academic theory-babble.) There’s still a problem, though. This is like saying that language can generate an infinity of universes with, say, stars in them. However, only a minority of these stars will acquire planets; and only a minority of these planets will engender living ecosystems; and only a minority of these ecosystems will produce self-aware intelligence. Combinations of words appear to give off a sparkle of “meaning,” no matter how vague or tantalizing, because our brains have evolved in tandem with language. The semiotic impulse hardwired into the human neocortex and triggered by early language experience perpetually strives to assign meaning to any potential sign-system. But where the average density of meaning is thin, the mind tires after a while of seeking it (and, arguably, creating it), and turns to richer, more organized zones of signification—ones where the rifts, as Keats put it, are “loaded with ore.”

To shift analogical ground: the language, with its dense web of connotative links, is itself like a vast virtual brain, to a version of which each of us has access. In this virtual brain, connotation forms the “axons” and “dendrites,” the connective fibers, of word-neurons, while syntax makes up the coherent paths burned along these connections. Within patterns of connection in the language-brain, as in the biological brain, memories are stored. Since this virtual brain is very largely a copy or clone of the same one used by all other speaker-writers, the vast bulk of the memories held in the language-brain are not our own, but are the shared experience of countless people through generations, growing less specific and less consciously available the further back in time one reaches toward etymonic roots and grammatical origins. What’s more, all these personal copies of the language-brain are in continual communication with many other current copies through daily social interaction as well as via the mass media—and in communication with earlier “editions” via reading, viewing old films, listening to old recordings, and so forth. Yet crucially shaping the personalization of each copy of the language-brain is its possessor’s actual material and emotional life. This life, no matter how much it is shaped, like the language, by historical and social forces, is also unique and, however infinitesimally, is itself part of these forces and shapes the social and physical as well as the linguistic world. To paraphrase Marx: “People make their own meanings, but not with a language of their own choosing, rather, with a language given and transmitted from the past.” Finally, it is the experiencing biological brain, the living body in the social timescape, that brings this virtual brain to life, maintains it moment to moment, thinks it and thinks with it.

In this thinking, when we write poetry, there is a necessary suspension, a “float,” whereby we make space for the new and appropriate word or phrase to appear. This suspension is analogous, in my quantum-cosmological model, to the moment before the collapse of the wave function, when the photon goes one way or another as I observe it doing so. For purposes of the analogy, it doesn’t matter whether I somehow unconsciously “choose” for the photon to go one way rather than another—or whether one “I” chooses to inhabit the universe in which the photon goes that way, while another “I,” brought into being that moment, “chooses” the universe in which it goes the other way. Or—if we are loyal followers of Einstein, who hated to think that God plays dice—we could say that the universe chooses for me which way the photon will go. And it is a truism that in writing well, we often have the sensation of receiving words from a mysteriously familiar “elsewhere.” This source may also feel like an “elsewhom,” a power beyond our conscious control, but one with which we have entered, momentarily, into a covenant like the ones the Greeks often made between themselves and the gods. The basis of this covenant was the similarity between humans and gods, their common ancestry as children of Earth and Sky, Time and Space.

What, then, is the “universe,” the bigger, smarter source that chooses the words for us? I would argue that it is a state of the language-brain conditioned by my consciousness, existing only in interaction with it. This is the covenant. So that what writes is neither “I,” nor “language,” but I-in-language, the self-process of experience and desire mapped onto the language-web, physical brain and virtual brain acting together. In this moment, biology fuses with society, history with Now, the many with the one. Because this is so, the writing has meaning. And the more closely my experiences and desires, perhaps unrecognized until this instant, are mapped by my attention onto the language-web, the more sharply my imagination reveals huge patterns of protosyntactic paths in that web lit up by those experiences and desires. The synapses, the spark-gaps, in these paths are the differences between my unique experiences and desires and the similar yet different experiences and desires, conditioned by the same large historical and biological forces but varying by circumstance, of many others. The more of these I perceive, the more meaning I-in-language make, reaching asymptotically toward infinite density. Connotative links at this point are not merely nonlinear; they achieve a complexity and infoldedness like that of the seven-dimensional space around the nucleus of an atom. If I have trained myself well, so that I can maintain that suspended, neutral, yet passionate focus, I can release at least some of those path-patterns via the nerves of my arm and hand onto the paper. “The clock ticks, the page is printed.” (Ted Hughes, “The Thought-Fox.”)

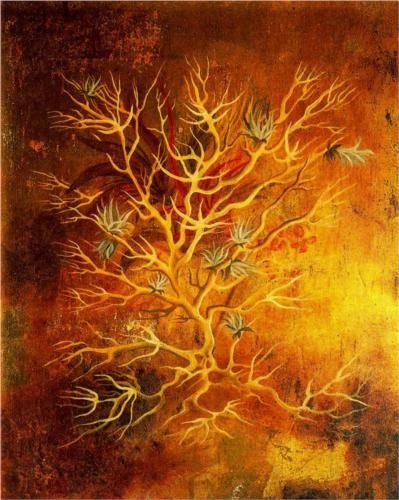

Attention is the key to this process, but imagination is the door[….]Poiesis, in the deepest sense, is cosmology. Moment to moment, we imagine our way across the branching and joining of universes, telling the story of ourselves in the Language behind languages that Heidegger says is the same as Being. Poetry enacts this forest of journeys in the words we have. It is this poetic process, not raw combinative potential alone, that gives language its savor of the infinite, as it is we, living and finite in space and time, who animate its immensity into intelligence.

Quantum poetics