R.U. Sirius

It is not every day that after your science-oriented literary reading that you, the other writers who read, and the audience climb through a dog door into a small, astronomical observatory that was constructed in the art gallery where the reading took place to see a live-feed projection of the dog star Sirius — the brightest star in the night sky and so nicknamed due to its containment in the constellation, Canis Major — from a telescope mounted on the roof of a nearby science education center. This event, which to my mind represents an example of what Alfred Jarry calls an "imaginary solution" where exceptions are the rule, happened a few nights ago in Philadelphia at The Print Center, where I read with Jena Osman and Allison Cobb in conjunction with Demetrius Oliver’s minimalist, meta-spacefaring exhibition, Canicular.

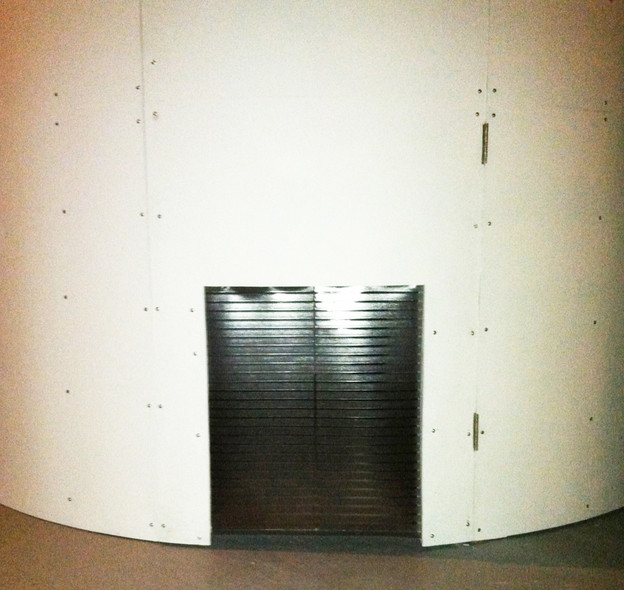

Messier by Demetrius Oliver, courtesy of The Print Center

After the reading and before we were led through the dog door by John Caperton, The Print Center’s Jensen Bryan Curator, Caperton gave us a tour of the rest of Oliver’s exhibit, which includes a sign outside the gallery depicting an image of dog fur created by Oliver, an audio component of Oliver on a dog whistle (inaudible to human ears) broadcast from the front of the building, and video monitors depicting a sculpture by Oliver of a mechanical model of our solar system. During the tour, as Caperton talked about the dog star Sirius and its role as a symbol in belief systems, creation myths, and occultisms across cultures and times, I was thinking about the cosmology of the Dogon people of Mali in Western Africa. The Dogon, according to some researchers, had advanced astronomical knowledge by understanding that Sirius is part of a binary star system whose second star is an invisible white dwarf. I also thought about Nathaniel Mackey’s Andoumboulou poems, which invoke a Dogon funeral song. And who can forget cyberculture provocateur and transhumanist R.U. Sirius, co-founder of Mondo 2000—

Three photographs I took of the live-feed projection of Sirius showing the projector (the smaller light above) inside the observatory

Bringing installation art, photography, astroscience, and cross-genre forms of poetry and prose informed by the natural sciences into conversation, the literary reading, curated by Jena Osman, enacted the increasingly collaborative and transdisciplinary shifts occuring in the way that practitioners across the arts and sciences are presenting their work to more diverse audiences. Osman read excerpts from her project, Popular Science, a visual-textual work on neuroscience and the nineteenth-century “quack-science” phrenology in which Walt Whitman, Margaret Fuller, and others participated. Osman also presented her interactive digital poem, “The Periodic Table of Elements According to Dr. Zhivago, Occulist,” which I have adored since it first went online in the late 1990s. Allison Cobb, who works for the Environmental Defense Fund, presented from her project, Plastic: an Autobiography, an investigative, documentary work addressing the destructive and ever-present role of plastics in the Anthropocene, a geological term, she explained, given to mark the impact of human activities on the Earth’s ecosystems. I read the chapters, “WMAP,” named after a NASA space probe, and “Shared Axiom,” a ’pataphysical sex scene, as well as a poem, “Eleven Asteroids (Dimensions),” from my book, Starlight in Two Million: A Neo-Scientific Novella, which explores the fourth dimension in physics, where space meets time in relation to “4th person narration,” a concept introduced in Shanxing Wang’s book, Mad Science in Imperial City (Futurepoem, 2005).

Out of all the material read that evening, it was Cobb’s project that got closest to referencing Oliver’s dog star muse for his exhibit with this image that she presented of her dog Quincy with a plastic car part that turned up in her front yard, which has come to form the core of her literary investigation into the biological and environmental sciences:

Quincy the dog with car part from Plastic, an Autobiography, courtesy of Allison Cobb

I.M. Sirius

Quantum poetics