The new face of Chinese poetry

It is impossible to convey the baffling complexity of the Chinese poetry scene, or rather scenes, for China is a huge and fragmented country with thousands of poets spread across millions of square miles. Further, China is but one of several countries or “renegade states” (as some Chinese politicians refer to Taiwan) in which poetry is composed in the Chinese language. It is nonetheless possible to observe some general trends, of which the most salient, in my view, is the impact of the Internet. While many scholars have described the Internet’s influence on the publishing and consumption of Chinese poetry, I have yet to see anyone discuss the profound influence that it has had on the form and content of Chinese poetry.

At the risk of sounding cynical, most poems written in China today aspire to the condition of an elevated blog entry. The poster child for this trend is Yin Lichuan, the most prominent and influential member of the still controversial (but no longer active) Beijing-based Lower Body Movement, which was the first poetic movement to write about sex, adultery, drugs, crime, bar life, lowlifes, and other unsightly blemishes on the grimy underbelly of China’s new urban culture. Now, however, she is but one of hundreds and possibly thousands of Chinese poets who write in a similar vein.

Interestingly, although the Internet and Internet culture have also had a profound effect upon poetry’s presence and prestige in Taiwan, poets in Taiwan have responded rather differently to this new media landscape, embracing print publication and book arts, although they too now seem to be moving in the same direction.

But China first.

The late nineties and early years of our new millennium — when Chinese poets began going online — saw online poetry forums, bulletin boards, and journals spring up like mushrooms across the Chinese Internet. Although many of these ventures were relatively short-lived and had few readers to speak of, others became hugely popular alternatives to print publication. These included the Shanghai-based Under the Banyan Tree; the women’s poetry journal Wings, operated out of Beijing; and Poetry Vagabonds, whose servers and moderators were located in the Guangdong area. Although these sites typically relied upon a visually unattractive HTML format, they allowed readers to instantly post comments and exchange messages with authors and other readers, which created extraordinarily active online communities, at least for a time.[1]

For many readers, or “net-friends,” to borrow the Chinese term for Internet users, interest in poetry was fueled by the opportunities it provided for social networking, particularly for those living outside major urban areas who enjoyed little if any access to poetry books or poetry-related events. However virtual and fugitive these communities may have been, they allowed scores of “outsider poets,” Yin Lichuan among them, to cultivate a devoted following. Even once software for creating personal blogs became easier to use and poets abandoned these collective platforms, their followings tended to remain. While a few of these online forums and journals persist, the quality of the poetry and the quantity of the posts have fallen off dramatically, and many of the more prominent avant-garde venues, such as Poetry Vagabonds, have been inactive for years.

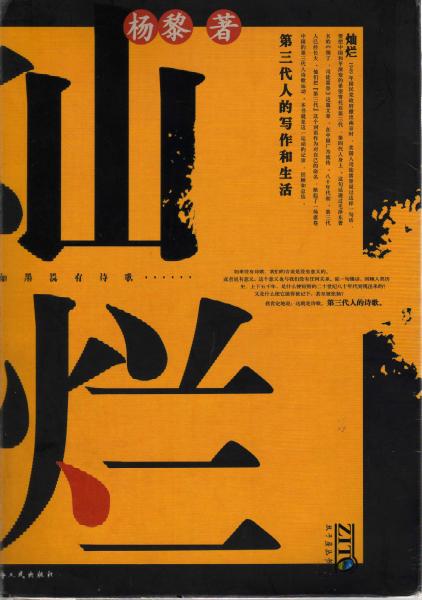

The alpha male of this vast tribe of virtual “escribitionists” is probably Yang Li, a “third-generation” poet who rose to prominence in the eighties, long before most people in China had heard of computers, much less the Internet. The fifty-six-year-old Sichuan-based poet learned how to go online only in 2000, but he took to the new medium readily. Yang Li’s poetry is, to put it mildly, an acquired taste, for much of it consists of tell-all confessions on provocative topics such as the rights of sperm or why he has lost interest in giving oral sex as opposed to receiving it. Indeed, his most famous poem is an epic-length meditation on “The Big Cannon,” a Chinese euphemism for masturbation.

Yang Li's Glorious

Yang Li’s obsession with sex can be read as an example of the return of the repressed. Like other poets who grew up during the Cultural Revolution, when nearly all books without the party stamp, including collections of classical poetry, were routinely seized from private homes and destroyed on the spot, Yang Li had little exposure to poetry besides some then-banned classical poems a neighbor would recite to him and the poems of Mao Zedong, in an irony that makes me wonder about the Chairman’s commitment to socialist realism and the proletarian revolution, were written in a classical form dating back to the Song Dynasty.[2]

There is, of course, the much simpler explanation that sex sells or at least prompts hits. But this should not be reason to write this poet off. As his first English translator Simon Patton has noted, Yang Li’s poems are all the more engaging for their apparent lack of craftsmanship.[3] For instance, “Albania,” which was inspired by a socialist propaganda film the poet was forced to watch in his youth, is a most engaging depiction of life during the Chinese Cultural Revolution. Even his more provocative efforts, such as “Spring Days” and “When We Eat We Never Talk about Sex,” have unexpected depths. Written in Beijing some five or six years ago, they bear witness to the massive transformations that city underwent in order to become the symbol of China’s emergence as a major world power.

As urban historian Hanru has aptly observed, “the traditional substance of the Chinese city is the hutong — a mat of courtyards impressive for its intimacy and versatility, but often casual in its construction.”[4] Beijing in particular was once a perfect warren of close courtyards and narrow lanes, but these have been swept away to clear the ground for parking lots, skyscrapers, and huge, multistory condominiums such as the one Yang Li describes in “Spring Days.” Seen in the light of this new urban reality that isolates people even as it forces them together, the poet’s account of the deterioration of his relationship with “Ms. Chrysanthemum Wang” and “Xiao Yang” can be read as both symptom and critique of the general loss of intimacy and community that have followed China’s efforts to reinvent itself as a modern urban society.

Virtually every major city in China has experienced a similarly traumatic makeover over the past two decades, and the infusion of global capital and commodity culture has done much to diminish the presence and prestige of poetry in a nation that, for more than two thousand years, regarded the writing of poetry as its most revered cultural practice. In the eighties and early nineties, when even outsider poets enjoyed an almost heroic status, poetry readings were major events, in part because there was so little else for people to do during their leisure hours. Unlike in post-Maoist China, where “to be rich is glorious,” poets did not have to compete with the likes of cable television and tabloid news, pirated videogames and DVDs, porn, shopping, or those most alluring and addictive practices of eating out and playing the stock market, as Zhang Er describes in her prose piece “The Husband of a Younger Cousin on My Father’s Side.” Moreover, as tea houses have been gradually replaced by Starbucks-style coffeehouses, fast food restaurants, karaoke bars, malls, and other urban spaces where muzak, video streaming, and the endless chatter of cell phone and laptop conversations make it all but impossible for anyone to read aloud, there are fewer and fewer places where poets can present their work in public, assuming of course that anyone would want to hear them. As Yu Jian’s “Executing Saddam” suggests, with the invasion of cable television and American-style news programming, even the private home has become subject to the intrusions of an aggressive visual and consumer culture that has little room for poets or poetry. Small wonder that China’s poets have turned to the blog and in their effort to reach out to readers have reshaped their work to fit this more intimate format.

Zhai Yongming (in red) at White Nights

The “blogification” of contemporary poetry in China has had a tremendous leveling effect on individual style even among poets who came into their own before the Internet. Take the work of Zhai Yongming and Yu Jian, for example. In the nineties, the breakout decade for both, their poetry had little in common in terms of form or content. Zhai, who runs “White Nights,” a wine bar in Chengdu, and used to write elegant free verse that is deftly captured in this translation by Andrea Lingenfelter:

For Women Poets

They say:

Don’t worry your pretty little heads over poetry

Their desks piled high with

Ink cartridges, CD-ROMs, blank paper

But we

want it all:

an iBook Estee Lauder

a printer paint and powder

When I stand beneath a concrete ceiling

Its geometric structure abstracts into a heart

I even fancy I could snatch that cube

for my own personal compact

Some years ago from an airplane

I looked down and saw those carbon dark strata

They’d passed through prehistory acquired significance

How long ago was that?

Before there were women or men[5]

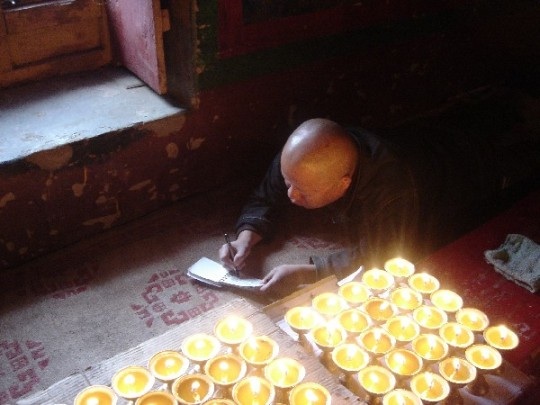

Yu Jian, on the other hand, is regarded as one of the founding fathers of post-Soviet Chinese poetry and lives in the relatively remote province of Yunnan, where he has spent much of the last decade documenting the natural and cultural life now threatened by rampant development. Yu Jian established his reputation as the author of Whitmanesque inventories comprised of telegraphically short phrases sprawled across the page. His signature work and magnum opus, File 0, is a twelve-part prose poem modeled on the personal dossiers the state once compiled for virtually every citizen in the country, covering the whole lifespan, from elementary school until death:

5 thought report

(brought to light and compiled on the basis of conjectures and suspicions of comrades with

a grasp of the particulars)

he wants to bellow reactionary slogans he wants to violate the law and public discipline

he wants to go into a frenzy he wants to be degenerate

he wants to rape and defile he wants to strip naked he wants to go on a killing spree he

wants to rob a bank

he wants to be a billionaire a big landlord a big capitalist wants to be king president

he wants to lead a life of debauchery dissolute to the nth degree be a local despot act

the tyrant ride roughshod over the people

he wants to surrender he wants to betray he wants to give himself up he wants to make

a political recantation he wants to turn against his own side

he wants to riot take frequent action rampage rebel overthrow a class[6]

Both poets, however, now write colloquial confessional verse that is not all that different in style and register from that of Yin Lichuan, Yang Li, and company. Although there are important differences in their work, the distinctions have much less to do with form than with content, tone and degree of irony or confessional disclosure.

To be sure, there are a number of important Chinese poets whose work has remained relatively immune to the trend I have just described — Bei Dao, Duo Duo, Han Dong, Xi Chuan, Zhang Er, and the late Zhang Zao, who passed away earlier this year, come readily to mind. However, most of these poets either live outside China or are employed by Chinese literature or foreign language departments that reward or require them to publish their work in books or print journals. There are also many performance poets who write with a view to public recitation, but the vast majority of these poets are salesmen (or saleswomen) for commercial ventures or the Communist Party, or rank amateurs with naïve dreams of being snatched from obscurity.[7] Among the exceptions worth mentioning is the rocker poet Cui Jian, whose songs and lyrics are almost as famous in China as Bob Dylan’s and Leonard Cohen’s are in the English-speaking world. Yan Jun, whom I had the pleasure of seeing perform a few years ago in Taipei, combines computer-generated soundscapes and video clips with a recitative style that simultaneously evokes religious incantation and the iconoclastic antics of the edgier sound poets. His Dutch translator Maghiel van Crevel astutely observes that Yan Jun’s poetry “qualifies as nothing less than theater,” but very few poets in China have followed his lead in exploring the possibilities of multi-media.[8]

I suspect the trend toward “blogification” will continue until something more alluring replaces the blog, but it is hard to imagine what that might be, as most of the other Internet services and technologies that could conceivably provide an alternative platform and template for poetic composition and social networking, such as Facebook, Myspace, Twitter, and YouTube, are more often than not blocked by the Chinese authorities. For better or for worse, the personal blog seems destined to remain, for the immediate future, the platform of preference for the lion’s share of poets in China.

If the blog entry is the current default setting for poetry in China, this is not yet the case in Taiwan. Here, too, the rise of the Internet and the proliferation of blogs, coffee houses, videos and other forms and forces of commodity culture and globalization have had a drastic impact on both the readership for poetry and the genre’s presence and prestige in the society at large. Poets on this side of the Formosa Strait, however, have been much less willing to abandon the book for the blog. There are several reasons for their persistent investment in print culture. For one thing, during the martial law period of the Nationalist government or Kuomingtang (KMT), which lasted from shortly after World War II until 1987 — the longest martial law reign in modern history — poetry enjoyed an enviable currency and centrality thanks to the prevalence of coterie journals, newspaper literary supplements and state-sponsored poetry competitions that actively sought interesting lyric poetry and paid contributors a respectable fee for the privilege of publishing it as a distraction from divisive political and social issues.

For the same reason, the island’s major poets, most of whom were former soldiers who had fled to Taiwan after the “fall of China,” turned to surrealism and other Western modernist movements so as to avoid state discourses of “anticommunism” and “moral reconstruction” without prompting the ire of the army of censors employed to keep a lid on public criticism of state policies.[9] Many of these “second-generation modernists” who came up in the late fifties, sixties and early seventies, such as Guan Guan, Ji Xian, Zheng Chouyu, and the late, great Shang Qin, who passed away last June, became household names during the martial law period. Even after this period ended, their reputations were so firmly established that they felt little need to alter their poetics or to turn to the Internet as an alternative to print publication. Quite a few of them are contributing editors to the literary journals and newspaper literary supplements that continue to publish poetry, or serve as judges in the highly-publicized poetry competitions these publications regularly sponsor, which has helped to keep the genre alive.

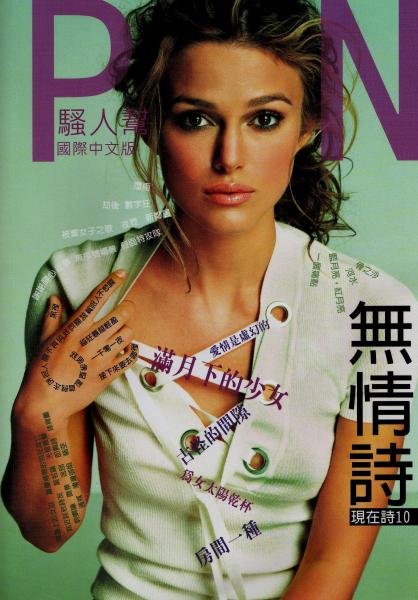

Although Taiwan has had its share of Internet poetry forums, bulletin boards and blogs, even avid Internet users still prefer to publish their verse in print form. Indeed, the triumph of the Internet in other spheres of life seems to have intensified the desire for print publication. This may have something to do with the island’s relatively small size and the concentration of its population in the greater Taipei area, which diminishes the difficulties of distribution, promotion and public recitation. Another possible reason is the growth of specialty bookstores and upscale bookstore chains such as Eslite that rely upon poetry and poetry-related events to advertise their cultural sophistication and are always on the lookout for novelty publications that can be used for book displays and point of purchase items. But the biggest reason for this persistent investment in print culture is the publication of the avant-garde journal Poetry Now, which since 2002 (as I have written in Jacket) has “served up more interesting verse in more interesting formats than the rest of the island’s journals combined.”[10] Their newest “Heartless Poetry” issue, for example, is designed along the lines of a glossy fashion magazine sans stories, with each page containing one or two poems set against a backdrop of digitally retooled, full-color ads stolen from the pages of the journals it imitates.

The pioneer here was Hsia Yü, who was one of the founding members of the journal and the driving force behind its emphasis on rethinking the possibilities of the codex book and enlarging the notion of the poetic text. Hsia Yü was the first poet in Taiwan to insist on designing her own books, which she fills with poems that draw attention to the book as a material object and to reading as a visceral and sensual practice.[11] Her innovations in poetic form, content, composition, and book design, which rival those of Johanna Drucker and Keith Smith, had a tremendously liberating influence on the island’s younger poets, many of whom subsequently joined the Poetry Now coalition or contributed to its publications. In particular, poets such as Hung Hung, Amang and Ye Mimi, have followed Hsia Yü’s example by designing their own books or hiring someone to do so. Their publications have helped to prompt a renewed interest in book design that has included such innovative formats as “big character” wall posters, accordion books, poetry calendars, “Poetry in an Egg,” “Poetry in a Matchbox,” “Poetry in a Sleeve,” and other novelty items. These innovations have encouraged concomitant experimentation in poetic style and content. While the poetry that has been published in Taiwan these last seven or eight years is not necessarily better than what has appeared in China, it is certainly more stylistically diverse and lends itself to more diverse forms of engagement: as aesthetic object, as gift or intimate possession, as script for recitation or browsing.

But there are downsides to this investment in novelty. Not only are many of these publications difficult to come by and relatively expensive, many of the best poems lose something in translation when they are reprinted in anthologies or posted on the Internet by the growing number of readers who prefer to read poetry on a computer screen. Hsia Yü’s “Tied Up and Waiting” and Ye Mimi’s “Sunlight’s Dotted Line,” for example, both have a flirtatiousness and musicality that make them a pleasure to read in almost any presentational format, but their closing lines make little sense outside the pages of a book. What is lost in the translation to the screen is fairly obvious in the case of Ye Mimi’s poem, but I should probably point out that the volume for which “Tied Up and Waiting” was originally published had a sewn binding and uncut, untrimmed pages, and was comprised of poems that play off the various ways in which authors attempt to ensnare readers and how readers, in turn, accept, resist, or ignore these enticements.

The other downside to this investment in novelty is that it eventually runs up against the law of diminishing returns. Here, too, Internet culture has become increasingly hard to resist as attention spans shrink and more and more people spend less and less time reading and tend to browse even when they do read, which helps explain why the new Poetry Now was designed to look like a glossy magazine. The oft-quoted paradox that there are more people writing poetry than reading it is not that far from the truth in Taiwan. Most poetry collections and anthologies published in the past few years have had few if any readers and simply molder on dusty shelves in the remote corners of bookstores if they manage to get into the stores at all. Moreover, the institutions that once generously supported poetry readings have not been unaware of this diminishing interest. Last year was the first time in almost a decade that the city of Taipei failed to host the Taipei International Poetry Festival, which was cancelled in order to free up funds for the International Flower Show. Several of the more established newspapers and journals continue to consider poetry submissions for their literary supplements, but the poems they publish tend to be but a few lines in length and read more like jokes than poetry, which has prompted some literary critics to predict the triumph of the “Twitter poem.”

This is a depressing trend, so much so that I sometimes wish I were in China rather than in Taiwan. But then again, when I’m online, I often am.

1. There are many articles in English on Internet poetry communities in China, of which the most informative I have read is Michel Hockx’s “Virtual Chinese Literature: A Comparative Study of Online Poetry Communities,” in The China Quarterly 183 (2005): 670–691.

2. The source for this information is an interview of Yang Li, forthcoming in Full Tilt: A Journal of Poetry, Translation and the Arts 5.

3. Simon Patton, “Yang Li,” in the Chinese section of the online archive Poetry International Web.

4. Hou Hanru, “Beijing Preservation,” in Content, ed. Rem Koolhaas (London: Taschen 2004), 454–465.

5. This translation originally appeared in Full Tilt 3 together with an interview by Andrea Lingenfelter, whose collection of Zhai Yongming translations, The Changing Room, is forthcoming from Zephyr Press.

6. My translation of this section of Yu Jian’s “File 0” is indebted to Maghiel van Crevel’s version, which was originally published in its entirety in Renditions 56 (2001): 19–23 and subsequently reprinted in Maghiel van Crevel’s Chinese Poetry in Times of Mind, Mayhem and Money (Leiden: Brill, 2008), together with the Chinese and an extensive commentary (223–280). Readers are also directed to Robert Hass’s “Two Poets: A Generation after the ‘Misty School,’ Chinese Poetry Has Come Alive,” in the online journal The Believer (June 2010).

7. John A. Crespi has several articles and interviews on performance poetry, most of which are available online.

8. Chinese Poetry in Times of Mind, Mayhem and Money 471. The last and, to my lights, most interesting, chapter of van Crevel’s monograph is devoted to Yan Jun.

9. See Michelle Yeh’s “‘On Our Destitute Dinner Table’: Modern Poetry Quarterly in the 1950s,” in Writing Taiwan: A New Literary History, ed. David Der Wei Wang and Carlos Rojas (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006), 113–139.

10. “Is This the End of Poetry Now?,” in Jacket 35 (2008).

11. The best study of Hsia Yü’s poetry and agenda in any language is Zona Yi-ping Tsou’s MA thesis, “The Pleasure of the Work: Making Senses of Hsia Yü’s Poetry,” which I had the immense pleasure of directing.