Richard O. Moore’s poésie-vérité documentaries

Note: The following essay grew out of a talk given at the conference Les archives sonores de la poésie: Production, conservation, utilisation/Recording in Progress: Producing, Preserving and Using Recorded Poetry, which was organized by Céline Pardo (Paris–Sorbonne), Abigail Lang (Paris–Diderot), and Michel Murat (Paris–Sorbonne) at Université Paris Sorbonne, November 25, 2016. Many thanks to Garrett Caples for his help and scholarship, and to Richard O. Moore’s daughter, Flinn Moore Rauck, for her invaluable help and generosity. — Olivier Brossard

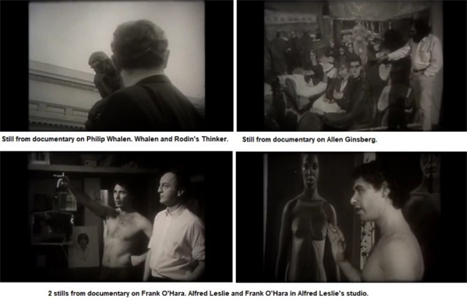

For scholars writing on the poet Frank O’Hara, one of the most fascinating documents is the National Educational Television outtakes from Richard O. Moore’s documentary series USA: Poetry (1966). The O’Hara film itself was broadcast in August 1966, shortly after Frank O’Hara’s death, offering the American public exceptional footage of the poet. In 2015, poet and essayist Garrett Caples wrote a series of essays on Moore, the first of which, “Work, or the Man Who Shot Frank O’Hara,” celebrated the publication of Moore’s first volume of poems, Writing the Silences (University of California Press, 2010). With subsequent articles published in 2015, Caples paid homage to Moore’s seminal work in the field of American letters: not only did Moore contribute to making American poetry better known to the general public from the mid-1960s onwards, but the poets he chose to shoot were, for the most part, far from being recognized at the time the documentaries were made. For a reader interested in the poetics, aesthetics, and politics of Donald Allen’s New American Poetry (1960), Moore’s tastes and choices were not only excellent but also prescient. For instance, Kenneth Koch and John Ashbery (USA: Poetry program #10) were not obvious choices for a filmmaker shooting a poetry documentary for educational television in the early 1960s.[1] Today, however, Moore’s films are considered invaluable archives of midcentury American poetry and poetics, as they documented the life and work of poets who have become some of the most influential writers of their time.

Educated at the University of California, Berkeley, Moore was part of the “circle of anarchist poets centered around Kenneth Rexroth in the 1940s — including Robert Duncan, Jack Spicer, Philip Lamantia, Madeline Gleason, William Everson, James Broughton, and Thomas Parkinson.” Moore soon stopped publishing poetry “to devote himself to a career in broadcasting, as a co-founder of the first US listener-sponsored radio station, KPFA, and later as an early member of the sixth US public TV station, KQED.”[2] It should be noted that Moore’s cinematographic work did not limit itself to the USA: Poetry series but embraced American culture and counterculture, as Caples writes:

Along the way Richard became an important cinéma vérité filmmaker, directing such works as Take This Hammer (1963), featuring James Baldwin; Louisiana Diary (1963), concerning the CORE voter registration drive; The Messenger from Violet Drive (1965), featuring Elijah Muhammad; Report from Cuba (1966), concerning Fidel Castro and the Cuban Revolution; and the ten-part series [sic] USA: Poetry (1966), which includes … films of Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Allen Ginsberg, Michael McClure, Robert Duncan, John Wieners, Anne Sexton, Denise Levertov, Charles Olson, Robert Creeley, and many others. He made two films with Dorothea Lange, Under These Trees (1965) and Closer to Me (1965), and two with Duke Ellington, Love You Madly (1967), and A Concert of Sacred Music (1967), and his later series, The Writer in America (1975), chronicled such figures as Toni Morrison, Eudora Welty, and Muriel Rukeyser.[3]

That Moore was first a poet is not a mere biographical detail: his intellectual formation and aesthetic disposition account for his cinematographic treatment of poetry. USA: Poetry program #1 on William Carlos Williams was produced by Craig Gilbert and directed by George Jacobson. Moore made the remaining thirteen episodes. At the time Caples was writing his essay, three episodes were considered lost (program #6 on Roethke, program #10 on Ashbery and Koch, and program #14 on Crane). In September 2017, program #10 was released on YouTube by poet Cody Carvell. Eleven programs are now available on PennSound.[4] The other films were kindly sent to me on a DVD by Moore’s daughter, Flinn Moore Rauck, whose help with this essay was invaluable.

To try to answer one of the questions raised by organizers of Les archives sonores de la poésie about the nature, status, and uses of poetry video documentaries,[5] I would like to argue that Moore’s films are all nourished by a tension between the archival impulse — they preserve poetry — and the “anarchic” impulse — the films go against the idea of the immutable, marble-like authority of the poet. This tension is born out of the filmmaker’s simultaneous desire to record and reluctance to immobilize his subjects, to have the last word about them, or to compose their definitive portrait. Moore’s documentaries are “anarchic archives” of the poets’ lives: resisting the canonizing impulse of literary history, Moore’s films show the poets in their natural habitat instead of sacralizing them or their work. True to the etymology of document, Moore’s documentaries never take the writers’ authority or authorship for granted: instead, they show “proof” and “evidence” of the works and lives of the poets.[6] By doing so, far from undermining the poems, Moore’s films reveal their beauty by showing that they are often hanging by a thread or a breath. The documentaries are not shrines; they’re a cup of coffee with Robert Creeley, an indescribable sermon by Brother Antoninus (William Everson), a good cry with Anne Sexton, a walk to the fishing cabin with Charles Olson: above all, the films are time spent and shared with the poets and their poems.

I would like to distinguish film from two other forms of archives: audio recordings and photography. Although films have soundtracks — they are, therefore, sound archives in their own right — they are also made of sequences of images. In Moore’s films, image and sound are equally important: the interactions between a visual sequence and an audio track often add a third intermedial dimension to the documentary. Caples calls Moore a “cinéma vérité” filmmaker, an interesting term as it raises the issue of the coincidence (or not) of sound and image. In Caples’s words, “cinéma vérité” hints at the realism with which Moore approached poetry and poets — when a conventional filmmaker would have gone for more traditional poetic decorum. Michael McClure rides his motorbike, John Wieners reads a poem in a dilapidated hotel room, Frank O’Hara explores the city among the “hum-colored cabs”: such examples show the filmmaker’s desire to go against traditional representations of poets and poetry. The genius of Moore is to have made films that are at once reportage and art: not only are they accounts of the poets’ lives and oeuvre, but their sequences of images and sounds attempt to embody the meanings of the poems, instead of merely illustrating them. Moore’s films are not about the poems; rather, they can be seen as extending and continuing them. They offer to do with sound and image what the poems say with words.

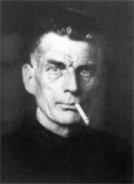

The distinction between film and photography is particularly relevant from an archival point of view. Writing on Lutfi Özlök’s portrait of Samuel Beckett (below, left; photographed a couple of years before Moore’s documentaries were made), Pierre Michon reflects:

L’année 1961. Plutôt l’automne ou le début de l’hiver. Samuel Beckett est assis. Il y a dix ans qu’il est roi — un peu moins ou un peu plus de dix ans: huit ans pour la première de Godot, onze ans pour la publication massive de grands romans par Jérôme Lindon. Rien n’existe en France pour lui faire pièce ou lui disputer ce trône sur quoi il est assis. Le roi, on le sait, a deux corps: un corps éternel, dynastique, que le texte intronise et sacre, et qu’on appelle arbitrairement Shakespeare, Joyce, Beckett, ou Bruno, Dante, Vico, Joyce, Beckett, mais qui est le même corps immortel vêtu de défroques provisoires; et il a un autre corps mortel, fonctionnel, relatif, la défroque, qui va à la charogne, qui s’appelle et s’appelle seulement Dante et porte un petit bonnet sur un nez camus, seulement Joyce et alors il a des bagues et l’œil myope, ahuri, seulement Shakespeare et c’est un bon gros rentier à fraise élisabéthaine. Ou il s’appelle seulement et carcéralement Samuel Beckett et dans la prison de ce nom il est assis en automne 1961 devant l’objectif de Lutfi Özlök, Turc, photographe — photographe esthétisant, qui a disposé derrière son modèle habillé de sombre un drap sombre pour donner au portrait qu’il va en faire un air de Titien ou de Champaigne, un grand air classique. Ce Turc a pour manie, ou métier, de photographier des écrivains, c’est-à-dire, par grand artifice, ruse et technique, de tirer le portrait de deux corps du roi, l’apparition simultanée du corps de l’Auteur et de son incarnation ponctuelle, le Verbe vivant et le saccus merdae. Sur la même image.[7]

L’année 1961. Plutôt l’automne ou le début de l’hiver. Samuel Beckett est assis. Il y a dix ans qu’il est roi — un peu moins ou un peu plus de dix ans: huit ans pour la première de Godot, onze ans pour la publication massive de grands romans par Jérôme Lindon. Rien n’existe en France pour lui faire pièce ou lui disputer ce trône sur quoi il est assis. Le roi, on le sait, a deux corps: un corps éternel, dynastique, que le texte intronise et sacre, et qu’on appelle arbitrairement Shakespeare, Joyce, Beckett, ou Bruno, Dante, Vico, Joyce, Beckett, mais qui est le même corps immortel vêtu de défroques provisoires; et il a un autre corps mortel, fonctionnel, relatif, la défroque, qui va à la charogne, qui s’appelle et s’appelle seulement Dante et porte un petit bonnet sur un nez camus, seulement Joyce et alors il a des bagues et l’œil myope, ahuri, seulement Shakespeare et c’est un bon gros rentier à fraise élisabéthaine. Ou il s’appelle seulement et carcéralement Samuel Beckett et dans la prison de ce nom il est assis en automne 1961 devant l’objectif de Lutfi Özlök, Turc, photographe — photographe esthétisant, qui a disposé derrière son modèle habillé de sombre un drap sombre pour donner au portrait qu’il va en faire un air de Titien ou de Champaigne, un grand air classique. Ce Turc a pour manie, ou métier, de photographier des écrivains, c’est-à-dire, par grand artifice, ruse et technique, de tirer le portrait de deux corps du roi, l’apparition simultanée du corps de l’Auteur et de son incarnation ponctuelle, le Verbe vivant et le saccus merdae. Sur la même image.[7]

In photography, the temporal, earthly body of the writer is likely to vanish to the benefit of the eternal body of the Author, as the portrait becomes iconic. Film, however, reintroduces time, blood, and motion into the temporal body of the writer: even if film is but a sequence of images, it is more likely to make the two bodies of the king-author coincide. A photograph is (a) still, a film, a moving sequence. When we watch the documentary about Charles Olson, we do not only see Olson, the bard of Gloucester, a myth onto himself; we also see a large man who’s impatiently trying to open a bottle of beer so that he can begin his reading with a bit of froth on his lips. Moore uses the time afforded by film to reinscribe the poets he’s shooting in our own (viewing) time. The body poetic that emerges from each documentary is the poet’s temporal one: text and poetry are but extensions of (physical) life. Moore’s documentary series is informed by democratic humility: as a director, he spent his time staging poetry as something experienced and written by his contemporaries — not everlastingly frozen in time, printed in a book. In spite of the admiration — soberly expressed by the narrator — for his subjects, Moore’s concern was to show that poems were of this world, not remote, but accessible; Moore’s manner thus went against the cultural grandeur traditionally associated with poetry (the flip side of its exclusion from the polis).

At the risk of stating the obvious, I will argue that Moore’s documentaries are metapoetic. The Greek prefix meta means “in the midst of; in common with; by means of; between; in pursuit or quest of; after, next after, behind.”[8] Moore’s films place us “in the middle” of poetry, “among” and “with” the poets, “between” words. The films are also coming and going “after” the poems. “Coming after”: I would like to see them as extensions of the poetic oeuvres they are about; not just secondary material coming after the poetic fact, but rather new manifestations and collateral benefit of the poets’ works. “Going after”: I would also like to see the films as exploratory works about poetry, not only looking backward to the works they talk about, but also looking forward to new understandings and new forms of artistic consciousness that they elicit. In their short fifteen or thirty minutes, the films do not have the pretention of coming to terms with the poets’ oeuvres. Nevertheless, because of their creative forays into poetry, Moore’s films should also be considered works of poetic research, offering leads and reading possibilities that the viewer-reader will be free to explore. The USA: Poetry films are metapoems: as works of cinematic art, they are in the middle of the poems, among and with them; but they also displace the poems onto the medium of film, not to blur the boundaries between images and words so much as to reveal what makes a poem a poem. They are metapoetic because they reveal the genericity of poetry at the same time as they reveal the specificity of the moving image. They are not vaguely about someone’s poems; they are precise explorations of the nature and life of words in poetry. In that sense, Moore’s films are works of art as well as highly sophisticated and insightful research objects. I will try to assess their metapoetic nature by first looking at them as “motion” pictures which place the viewer in the midst of the new faces and bodies of poetry; I will then look at the hybrid visual-verbal body of film and show that Moore’s documentaries are doing their own share of screen writing. Lastly, I will focus on a sometimes forgotten dimension of film: sound. Moore’s documentaries are metapoetic because they are talking pictures, conjuring all possible phonic elements (breath, voice, sounds), sometimes breaking into song.

“Do you feel it?” poet Ed Sanders asks at the end of “his” documentary. Moore’s films are invitations not only to listen to poetry, but to feel it in their incredibly rich interactions of image, sound, and text. Instead of archiving (as in filing) poetry, poems, or poets, Moore made sure to keep his subjects in print, on film, in circulation. Before being conceived as archives, recordings, or traces of the poets’ works and lives, the films were meant to be broadcast to viewers across the US. In that sense as well, the films were and are the extension and continuation of poetry.

1. “Motion pictures”: in medias res, in medias corpora

1.1 Not still(s), films

All of Moore’s documentaries provide bio-bibliographical statements — usually brief — at one moment or other. Rather than being expounded in full detail, the poet’s biography is also often hinted at in various scenes. In most of the documentaries, at least half of the film is devoted to the poet reading her or his work. The documentaries are all fifteen minutes long, except for those on Anne Sexton and Robert Creeley, which are thirty minutes each. Although they were made for educational television, the films offer little if no commentary or explanation of the poems or situations: Moore’s narration merely shows the poets in their everyday life and environment. Moore’s poised voice alternates with the voices of the poets who read their poems, or whose voices are sometimes used as an alternate form of narration (Sexton, for instance, reads her biography, and some of the poets’ voices are used as voice-overs).

Calling Moore’s films “motion pictures” may be stating the obvious again: they indeed are animated sequences of images. However, I believe that Moore was particularly sensitive to the mobility of cinematographic images, as his documentaries are all about movement, about poetry as an art of (and life in) movement. Moore uses movement as a way to steer clear of any mythologizing temptation, whether on his part or on the part of the writers he is shooting. There is something very humble in his presentations of the poets: the film director-narrator does not impose himself on his subjects; the latter are also presented in unpretentious light, as Moore brings them close to the spectator. Moore’s aesthetics of humility has to do with the way he moves his camera to record the motions of the poets. Each film presents various forms of movement, some more obvious than others.

Philip Whalen’s alert gait as he leaves his home to go for a walk contrasts with the stone solemnity of his destination, the San Francisco’s Legion of Honor courtyard with the statue of Rodin’s Thinker in its center. Gary Snyder is also constantly on the move: he is seen arriving at a reading venue on a motorbike bearing the inscription “end the war” on the gas tank. Such a theatrical entrance contrasts with the stark, minimalist setting of Snyder’s reading (empty apartment, grey background). An unsteady camera greets Anne Sexton — and us — as she descends the staircase of her home with a glass of milk in her hand. The jolts of the camera, as well as Sexton’s casual movements, give us the impression that we are watching a homemade family film: we are brought into an intimate circle. Brother Antoninus’s initial movement is that of the meditative walk, the meanderings of the mind, before he enters his monastery and paces the stage, delivering his sermon to his brothers. Even when the poets do not seem to move, the camera comes close to them and captures the flow of their lives: Creeley, for instance, does not come and go, as some of his peers do in other documentaries. His face, however, is a theater of infinite expressions captured by Moore’s camera.

Such examples could be multiplied almost indefinitely. Moore’s fascination for this incredible variety of movements, tirelessly recorded, serves one purpose: the poets’ moves and gestures bring not only them, but also poetry as a genre, to life. Moore shows poems to be the results of comings and goings, of processes and sequences. Poems, his films tell us, never just happen; they take time (and space). It’s a fragment of this time he is unfolding in front of our eyes in his documentaries, against the conceptions of poetry as a timeless genre.

No ideas but in medias res, such could be Moore’s motto as poet and director. His documentaries give the impression of placing the viewer in the thick of it all, in the middle of a discussion about poetry and poetics. Often the poet’s actions or conversation occupy the first minutes of the film before the narration introduces the poet to us. In that respect, Moore’s cinematographic art is informed by the aesthetic principles of openness claimed by 1950s and ’60s artists and writers, among whom were the poets of Donald Allen’s anthology The New American Poetry, who opposed the idea, popular with the New Critics, of the poem as autotelic text, self-sufficient and closed upon itself. Moore’s documentaries are open-ended films that give us the feeling that they have started before we started watching and that they will end long after we stop. His films overflow their beginnings and endings: as spectators, we are butting in, eavesdropping on a slice of life that continues after the end credits. The sense of continuity, the place and time the films point to beyond themselves, are just as important as what we are being shown. This may be where the educational value of Moore’s documentaries lies, far from any didactic intent: by making the lives of the poets parallel to ours, by inscribing them in a time sequence not neatly tucked in the limits of film, Moore’s art reveals the possibility of poetry. Poetry is time; “it’s the timing” which makes a poem a poem.[9] Poetry is mortal; it’s here and now, before being there, in a few moments.

1.2 “Our age bereft of nobility / How can our faces show it?”

The film on Robert Creeley begins as if we were sitting right in front of him, tête-à-tête. With no further ado or introduction, Creeley tells the viewer about his poetics:

My sense of writing is that it must be viable […] it has to be open to all that can confront it. If I wanted a sense of my life that I could offer something I actually believe in, I want to be ready to go at any moment. […] I want poetry to be as open to whatever can confront it, as something to be felt said. I want it to be free from proposals that say it must go this way it must go that way, but I want it to be as sensitive to the intimate occasion as it can possibly be.

Creeley’s statement could serve as an apt introduction to Moore’s films, which are meant to be open to all who could confront them, just as they are alert to the idea of poetry. The notion of confrontation is central to the way Moore films his subjects face-to-face.[10] Yet confrontation should not be considered in its hostile sense, but in the positive sense of facing, of looking in the face, directly: the films come into direct contact with writing. The superimposition of “NET presents” and “USA: POETRY” on Creeley’s face (in closeup) hints at Moore’s project: to show us the many faces, the incarnations of poetry.

Still from Moore’s documentary on Robert Creeley.

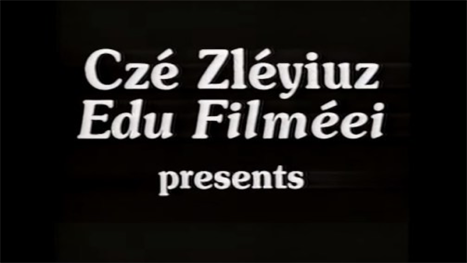

The difficulty presented by the first words appearing on the screen was twofold: in 1966, the “Educational” of NET might not have been the promise of an exciting program, as one may remember from Frank O’Hara and Alfred Leslie ironically placing the label “EDU” at the beginning of their 1964 masterpiece of cinematographic boredom, Pull My Daisy; besides, on the second screen, the word “POETRY,” spelled in a rounder typography, promised something for a genre known for its difficulty. Nevertheless, the presence of Creeley’s face, which occupies the entire screen, is a comforting promise: instead of being left with obscure acronyms (NET) and old-fashioned educational principles, we get to meet and talk to someone. The “printing” of USA: poetry on Creeley’s face is the promise that poetry is made by the people for the people, that it should be accessible to all, not reserved to a happy few.

Introductory screen to Alfred Leslie and Frank O’Hara’s The Last Clean Shirt (1964).

Introductory screen to Alfred Leslie and Frank O’Hara’s The Last Clean Shirt (1964).

Moore’s films approach faces and bodies very differently from Özlök’s mythologizing portrayal of Beckett. This is not just because the filmmaker has time and movement on his side, but also because his aesthetic choices (film setting and camera movements) go against the idea of glorification itself: Moore’s documentaries work at bringing together poet and audience, instead of separating them. One should add that most of the poets of the series were born between the 1910s and 1930s: many of them, affected by World War II, were trying to come to terms with an era of doubt and uncertainty, moving away from models of authenticity and originality. In “his” documentary, Robert Duncan explains that he considers himself as a “derivative poet,” and that unlike his predecessors Pound, Williams, and Stein, he is not looking for originality.

As he is saying this, the movement of the camera is remarkable: Moore zooms in on Duncan’s face, which reveals his thinking in progress, his hesitations and pauses. The camera allows the viewer to realize that Duncan is thinking out loud: as soon as his gaze chances upon the word “cow” on his wall, he launches into a long meditation on humanity, on the Maasai people, and on the idea of the primitive. At the end of his meditation, Duncan stops talking, as if surprised by the conclusion he’s reached; this passage, which Moore could have easily edited out, also reveals Duncan’s waiting for the director’s instructions. But above all, this short, essential moment in the film shows that even when the poet stops talking, his face speaks for him. These films are the films of faces. John Wieners, reading “A Poem for Painters” among the debris of the Hotel Wentley, states things even more explicitly as the camera zooms in on his shy face and nervous fingers: “Our age bereft of nobility / How can our faces show it?”[11]

Moore’s camera does dare to tackle “the face / and its torture” as his films tirelessly explore what surfaces on the faces, bodies, and surroundings (Duncan would say “households”) of poets. Only in film come images that reveal the interaction between textuality and physicality as the poet translates the words printed on the page back into the poet’s own body in the process of reading aloud.

1.3 In medias personas

In the chapter devoted to Gustave Flaubert in Corps du roi, Pierre Michon describes the masks of great writers as unwelcoming, imposing masks of authority. In Moore’s films, authority undergoes endless movements and changes. Even when we are meeting rather intimidating poets (Olson, for instance, or the rather highbrow Merwin and Lowell), the poets’ faces are inviting: they risk opening themselves to the camera’s gaze, showing themselves being subjected to constant fluctuations and revisions. At the beginning of the Creeley film, at the same time as the poet is making a firm statement about his poetics, he stutters, revealing his process of thinking in his hesitations, yet reaching a definite conclusion.

Writing about the mask Flaubert made by pretending he had no life outside of literature, Michon adds that it would end up sticking to his skin to such an extent he would no longer be able to lift it nor separate his body from this exclusive, invented life of literature.[12] In Moore’s films, on the contrary, poets are constantly lifting their masks (to the notable exception, perhaps, of Brother Antoninus). Even in the most theatrical performances — Olson or Ferlinghetti — Moore always shows the astounding variety of faces that poets put on for the camera’s eye. A conniving smile, an insightful glance, a questioning look, a momentary frown: Moore’s insistence on the infinite play of facial expressions underlines the theatrical dimension of the film. We are never allowed to forget that what we are watching is a performance.

When Olson reads, he points to the camera, gesturing toward the viewer as he is putting on his show. The camera zooms in on his face: it becomes our face, as if we were coming closer to Olson. The fourth wall of the film is breached, opened so that the viewer may come in: the spectator’s face becomes one among the faces of the poets; we can’t see our own face; it’s the flip side of the screen we are watching. But by looking at the camera and engaging with our gaze, the poets also invite our faces into the film. After Olson’s gestural reading comes an extraordinary moment when he is shown wiping his face like an actor: we are in the wings of Charles Olson’s personal theater.

There is, however, no distrust of acting in Moore’s documentaries; there is simply the director’s concern that everything under the eye of the camera, while being presented directly, be also shown as a form of acting. The films try to lift the mask of the actor at the same time as they allow the poet to perform with it.

Ferlinghetti puts on a mask, moves away from his typewriter, and proceeds to a rooftop as he is heard reading his poems in voice-over, thus connecting both etymologies of the word “person”: “mask” and “sounding through.” Not only is the face of the poet masked here, but his voice, asynchronous with the scene we are seeing, is at several removes: the voiceover was added to the film during the editing stage. Masked image and remote sound: everything is mediated by film. Interestingly, the poet ends up discarding his mask, and it is Ferlinghetti’s face (revealed frontally or hidden by a hat) that the film explores until the end. Instead of telling the viewers they will meet the real person, this passage insists on the infinite layers of theatricality afforded by the medium of film. The documentaries display Moore’s awareness of a paradox central to cinematographic art: film is mediated immediacy, a form of directness that withdraws its object at the same time as it presents it. Moore goes beyond this paradox by offering a direct connection not to the life of the poet qua actor but to poetry. Moore never deludes us into thinking that we will get close to the poet: this is no poetic reality TV show. The poets always escape, no matter how realistic and mundane the settings of the films. What does not escape, however, and what the spectators are left with, is poetry. This is what Moore’s films offer: direct access to poetry (itself a medium, and, as linguistic system, the reign of indirectness).

When Brother Antoninus is filmed performing what Moore describes in narration as “platform appearances, events which are the unique combination of poetry readings and direct encounters with his audience, encounters which have been described as embodying the savagery of love,” the camera is set at the back of the auditorium: we see not only the monk-poet but also his brethren in the audience.

The film therefore turns the monastery stage and auditorium into another stage for television, thus redoubling the theatricality of the performance. In this passage, the mutual insistence of the director and of the poet to show that it is but a performance is also an invitation for the viewer to accept it as such: by doing so, he or she will be able to establish a connection not with the poet (always staged at one or several removes, and not particularly welcoming in Brother Antoninus’s case) but with poetry itself. Quite paradoxically, Brother Antoninus solemnly affirms, glaring at the camera: “I don’t intend to act my way through it” after openly dismissing it: “the film is nothing, the camera is nothing.” At this particular moment whose theatricality is almost amusingly exaggerated, we are hinging on what Moore’s films dream of doing: just as Brother Antoninus is saying that he is not going to act (although he’s on a stage in front of an audience) and that he has no need for the medium of film, Moore aims at establishing direct contact not between the viewer and the poets, but between the viewer and poetry, words. To a certain extent, one could even say that there is a form of self-negation in the films (the extension of their humbleness): they are all saying “we are not what matters,” “we are nothing,” “the camera is nothing,” but “words are everything.”

1.4 The intimate theatre of poetry

Moore’s films usher the viewer into a theatre of intimacy where tension can always be felt between intimate realism and irrepressible theatricality. Creeley says that he developed a way of thinking about “writing in a way / so as to be intimate to a way of speaking.” Moore made Creeley’s method his own: his films are intimate to the poets’ ways of speaking, reading, and living; they are “sensitive to the intimate occasions” the lives and presences of the poets create in front of the camera. Moore’s documentaries are intimate (“from the Latin intimus, inmost”[13]) because they are archives of the temporal bodies of the poets, to keep in mind Michon’s distinction. I started my discussion of Moore’s films by reading the faces of the poets, but this analysis should also be extended to the precise choreography of their bodies. Moore’s films are physical archives of poetry: we meet real men and women, whose bodies stand in living contrast with various institutions and settings (Philip Whalen at the Legion of Honor in San Francisco; Gary Snyder in a zoo; Brother Antoninus in his monastery; Sexton at her home, by her swimming pool, or in the green suburban landscape of her neighborhood; Ashbery moving in Jane Freilicher’s studio). Because they move, the poets’ bodies offer the possibility of openness against closure (Snyder inside an empty room, Duncan and Wieners in a dilapidated hotel room, Koch in a telephone booth). O’Hara’s famous lines, “it is hard to believe when I’m with you that there can be anything as still / as solemn as unpleasantly definitive as statuary,”[14] could describe what the films do to our representations of writers and literature.

Moore uses film as a medium which is neither definitive nor solemn, and in this respect the poets’ bodies are his allies: Whalen’s head seems to thumb its nose at Rodin’s Thinker, for instance. On several occasions, film also reveals itself to be less definitive than painting: Ginsberg shows us a large canvas where his younger, shorthaired self is painted. Whereas the painting is fixed in time, Moore’s documentary catches the poet’s movements as he points to his own image. More strikingly, O’Hara’s tour of Leslie’s studio turns into an eerie juxtaposition of bodies, as a bare-chested Alfred Leslie shows his friend his new paintings of nudes. Against a backdrop of paintings, Leslie’s half-naked body is the image of life itself. In its ability to recreate the illusion of movement and life, film discreetly affirms its superiority over painting: the documentary is the archive of the living body of the creator (the painter) next to the inanimate body of the painted subject. Moore’s way of filming bodies through the use of close-ups and unusual angles hints at their predisposition to openness, their desire to “go onward” as Creeley used to say: the poets’ bodies become the essence of possibility.

As the poets read, Moore not only films the poet or the poem on the page: he records something altogether different that happens between the page and the poet, on the surface of the poet’s body. Moore captures the very moments when language becomes physical, an ephemeral extension of the poet’s body, when words go from page to eye to mouth, washing ashore on the poets’ lips. The documentaries stage the physical metamorphoses of poetry: the pages of Koch’s book are reflected in his glasses as his eyes read the poem and his lips shape the words. The pages are screens reflected in the screens of the glasses, mediated by the camera and the screen in front of us: what matters, however, is the direct flowing sequence of the film to show how language is going to leap from the lips of the poet. This indiscernible process (how stimuli go from eyes to brain to vocal expression made visible by mouth) is discretely staged.

Ashbery’s reading of “These Lacustrine Cities” is preceded by a sequence in which the poet blows cigarette smoke as his hand reviews a manuscript before the camera closes up on his face and lips. The activity of reading is framed by closeups: poetry is made by the body and the page is just an interface, a score for the body to translate words into air.

When Moore mentions O’Hara’s book Love Poems (Tentative Title), the film almost becomes sensuous as the camera comes and goes between O’Hara’s eyes, lips, chin, alternating side and frontal shots. Through the dexterity of his camera movements, Moore is making films about the erotic physicality of reading aloud, about the magic of taking words off a page and letting them out in the open air.

As trivial as it may sound, Moore manages to film poetry readings without making them boring, which is no mean achievement. And yet, his camera never adds to the scene or tries to illustrate the poem. Moore treads a line: he should avoid simply making a static recording of the poem or, on the contrary, heavily interpreting the poetry. His manner is subtle: by focusing on the physical economy of the poetry reading, on the theatricality of gestures, and on the face as the stage of a myriad expressions, Moore’s films become works of art unto themselves, films about filming (someone) reading writing. In that respect, the archives are not only the poets’ voices when they read; they are also their faces and physical demeanor: Moore’s documentaries are about the mutual transformation of the poet’s body and of the textual body in the process of reading aloud. Only a film can show such a transformation, make it seen and heard.

On several occasions, Moore shows us the poets in domestic situations, to the point that bodies themselves become domestic. We’re far from the majesty of the eternal body of the writer: one of Ginsberg’s friends walks around half naked in front of the camera; Ginsberg tells Orlovsky to zip up; Sexton comes down the stairs in what almost looks like a bathrobe or negligee; the name “Robert Creeley” is printed on the face of his daughter whose hair is being arranged by his wife. Such domestic scenes participate in the desire to show the poets as people of our world.

However, I would argue that, in the end, the only real intimacy achieved by the films — the only one they want to create — is one with the poems themselves. The only intimacy aimed at is the intimacy with the poets’ words as shared objects, as commonalities, something that film can pass on. We are invited into the poets’ surroundings, lives, invited to read their lips, to look at their bodies, but we can’t take that with us once the film is over. The words, however, are ours to take away, and the films our invitations to do so.

2. Screenwriting and telepoetry: film as extension of poetic content

To show and enact an intimate relationship between film and poetry: such is the ambition of Moore’s documentaries. They become extensions of the poems themselves, part of the poems’ economy and circulation.

2.1 Pen-typewriter-camera

In the middle of the Robert Duncan documentary, there is a long eight-minute sequence showing the poet at work on the poem “Passages 26.” Moore uses his camera to offer the viewer an intimate relationship not so much to the poet as to the process of poetry being written in front of the camera.

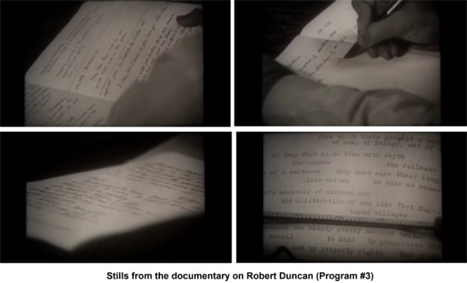

I would suggest that Moore’s montages make the process of writing and filming coincide. Such moments are most moving because these coincidences never serve a mythologizing agenda; quite the contrary. The aforementioned sequence opens on a closeup of Robert Duncan’s face while he is sitting writing. The camera dwells on his face dissimulated by his pen-holding hand, while a voice-over recording of his voice is played: “Last year when I wrote ‘The Architecture’” — he pauses before going on — “and … I wrote during that year twenty of these ‘Passages’ and numerous other poems.” This scene of the erasure of the poet’s face by the pen-holding hand, its coincidence with the evocation of poems written in the past, become significant when one realizes that Moore is interested in the here and now of writing in the here and now of the film. If the camera dwells on the concealed face, it’s because it is the face of poems past: the only thing we have access to is the writing itself, not the poet’s self. The camera moves from the concealed face to the notebook on the table: the writing is the only thing we keep from the past, our only connection to what was. In the subsequent minutes, however, Moore is going to film Duncan composing a section of “Passages 26,” always insisting on process. And film, to Moore, also a poet, is the art form capable of showing the writing process. The relationship between poetry and film is at its most intimate when the medium of film (as a sequence of images and sound) and the process of writing coincide. In this passage from the Robert Duncan documentary, there is perfect coincidence between the temporalities of film and writing as Moore shows Duncan in the process of continuing “Passages 26” in his own notebook. Duncan explains:

At the end of July I proposed “Passages 26,” and only got two lines — “They’ve to take their souls in war / as we take soul in the poem.” In this same notebook, along with this series of “Passages,” I have been working on a translation of a long poem by Victor Hugo. The opening line, “O god, whose work goes farther than our dream” drew me for my own purposes. So “Passages 26” now would now go — “‘They take their souls in war / as we take soul in the poem / O god for whom the work goes farther than our dream’ / Creator mysterious Abyss / from which there goes out a smoke / of men, of beings, and of suns!”

It’s particularly fitting that Duncan should reveal that one of the origins of this passage is a poem by Hugo, which he translates and works into his own poem. To some extent, everything in this scene is about translation understood as process and motion. What seemed arranged in a clear-cut and orderly way on the pages of the notebook with lines separating the passage written in July from La légende des siècles’s translated fragment now merges into the movement of writing: the camera shows Duncan’s translation morphing into the sequel to “Passages 26” being written right in front of us. Moore documents the moment when writing is happening in a way that insists on the dance of the intellect and of the body on the page. The same pen-holding hand, which was obliterating the face of the writer, is now seen dancing, the pen hovering over the page as Duncan stammers and hesitates as to what exactly he should write down:

“Mao’s … mountain of murdered men” — but that’s a lot of alliteration. … I can’t provide … you have to have that big mouthful of “Mao’s mountain of murdered men” — I can, at times, stare, and wonder “My God! what am I going to do with that?,” and have to do something with it. Alright … then … so … my consciousness of that must enter in here, and we … we’ll have the … [Duncan is shown writing] “the alliteration of ems like Viet Nam’s / burned villages / … irreplaceable / a hatred a the maimed (and bereft must) hold /against (the) bloody poetry America writes over Asia / (we must recall) to hold (by) property rights that / are not private (individual) or public rights (but / given properties of our common humanity).”

The fascinating three- or four-second moment — when hand and pen execute a dance above the page before writing down the words — coincides with the following sentence: “my consciousness of that must enter in here.” Hand, pen, and writing are the visible part of consciousness that film can reveal; or, rather, the only form of consciousness there is, the film seems to suggest, is that which can write itself down, after a moment of hesitation in its own limbo.

It is no coincidence that Moore goes out of his way not to shoot Duncan frontally in this entire passage — Duncan’s face either concealed or only partially shown, as the camera only reveals his profile or the back of his head. Here, intimacy is not so much about the poet as a person as about the direct encounter with writing happening. Writing is the only thing that matters, the film seems to say, and the only thing we can hold onto. The movements of the camera are to be understood as another layer of writing, the extension of the sequence hand-pen-typewriter-camera, which allows poet and filmmaker to show what is usually private, i.e., the poet in the very process of working. The documentary offers to be an extension of the poems by translating written text, marked and defined by separation (words as discrete entities on the page, passages separated by lines in the notebook, the mechanical clatter of the typewriter typing each letter, the typed-out poem crossed out by the metallic bar of the typewriter), into the flow of the poet’s reading out loud.

When Moore films Duncan reading aloud the section he has just written, the camera moves away from the page of the notebook to show Duncan in profile, slightly from behind, focusing on his hands now punctuating the reading in the air as a conductor would, the pen becoming Duncan’s baton. During this sequence, the camera moves as well, writes its own cinematic poem as it follows the handwriting from left to right on the diagonally placed notebook, but also the mechanical movement of the typewriter displacing text from right to left, to end on Duncan reading the poem he has finished typing: the camera moves downward slightly to follow his reading on the page, and the typewriter bar has to be lifted (a symbol of what the flow of film and voice does to separation, as they animate the text) so that the poet can read until the end of the printed page. Duncan tells us:

I had to develop a poetry where I could shift rapidly because I was not thinking and then writing it down but I was trying to, from many levels and many directions, and upstairs-is and downstairs-is, but, more than any duality, from all sorts of things, the flowing into a form of the things that belong to it.

Moore developed a film technique that also shifts rapidly, a way of shooting his subjects “from many levels and many directions,” up and down, sideways, trying to do with his camera what he thought the poetry was about. The intimate relationship between his films and poetry has to do with the ways in which his cinematic form responds to the poetic forms of the poets he chooses. In his hands-on approach to Duncan’s poetry, trying to get as close as possible to the writing itself, not in its mythology but in its practicality (Duncan talking about mistakes and the metaphor of the carpenter), Moore could be seen as a forerunner of YouTubers who make tutorials for their peers: in its movement from past text to present text being handwritten, then read aloud to be tested out, then typed, then read aloud in its final version, Moore’s documentary has an air of a step-by-step-DIY poetry tutorial.

In the documentary on Levertov, Moore films the poet as she is typing and revising a poem previously written in a notebook; here again, Moore plays with the movement of text, whether handwritten (the camera goes from left to right) or being typed (the page moves from right to left as it is being typed by the poet). But he complicates things further as he goes on to shoot the scene reflected in a mirror: the movement of the page of typed text is then the reverse. If Moore seems so interested in the movement of writing (whether handwriting or typing), it is because he questions the movement of poetry itself, in the age of television.

How does poetry move? Where does it go? How is it passed on? and how is it preserved? These are the questions that emerge from the motion of words and lines on screen. As she types, Levertov says:

I copy it out by hand several times usually before I get to the point of typing it and then in typing it I make various corrections and then when I think the poem is done, I copy it out in this notebook, because I always lose typescripts and this is something, you know, that I don’t lose, touch wood. … I don’t tend to lose these call books.

For Levertov, the poem as text is the result of a long sequence of handwriting-typing-handwriting again. This sequence is followed by her own reading of a poem. Film offers another way to move, preserve, and pass on the work not only as written or printed text but also as image and sound: a form of augmented poetic reality.

In the documentary on McClure, there is a moment when the film itself composes a poem as McClure flips a deck of cards inscribed with words in front of the camera: the screen becomes a literary kineograph or flipbook, and Moore tells us, “One of Michael McClure’s current experiments consists of cards with single words at the top and bottom of each card. The deck can be shuffled and random poems created. With a friend, the harmonica player, artist, and filmmaker Bruce Conner, the poem is improvised.”

There are two different poems in this passage: the one that McClure and Conner improvise together as they read the cards they were randomly dealt, and the one composed in front of the camera as the cards are flipped. In the latter case, there is no reading aloud of the poem; Moore has only a musical soundtrack (Conner playing the harmonica). It is then the responsibility of the viewer to read the poem, either silently or aloud. In this instance, I would say that it is less Moore’s camera that tries to do justice to the various forms of poetry than the very mode of composition of McClure’s poem which, in its succession of word-cards, is close to the technology of cinema. But what’s fascinating here is that in its staging, the poem depends on the motion of images, and on the viewer’s attention to receive and compose it: the poem is tele-transmitted.

2.2 From meta to tele

In the O’Hara documentary, Moore shows O’Hara and Leslie in the midst of writing a film script: at that precise moment, his documentary becomes a film about writing and making a film. As O’Hara reads aloud the pages he has just typed, the images of the two friends working in the studio are followed by footage of Leslie and O’Hara walking down New York City streets. Moore borrowed O’Hara’s reading of the film script as a new voiceover soundtrack for the documentary itself, blending it with various city noises: it’s as if O’Hara and Leslie were becoming characters in their own story.

Beyond some correspondences between O’Hara and Leslie’s script and Moore’s footage of the two friends in the city, what is fascinating in this sequence is Moore’s staging of the metamorphosis of writing, from the moment the words are conceived and typed by O’Hara on the page, to the moment they are read aloud in the studio, to their becoming a voice-over narration in a scene they were not necessarily meant for. Moore insists on the plasticity of the film medium as words, once freed by voice from the page they were printed on, can be moved, cut, edited in or out, associated with other sounds and images to which they have no prior relationship. But even when he insists on the many collage-like and intermedia possibilities of film, Moore never plays one medium (film) against another (writing). On the contrary, as Leslie is seen talking to O’Hara, voicing ideas that find their way onto the page as they are typed and then become, in a matter of seconds, a narrative for a fantasized film (O’Hara and Leslie walking in New York, their narrative being read aloud as a soundtrack), Moore insists on the precedence of writing as the necessary moment when thought and voice materialize on the page. The sequence tells us that writing a film is the hardest part: as soon as we have words, they can be voiced, played with, translated into or associated with images, in a matter of seconds. Writing, however, takes time, energy, and concentration.

At the beginning of this sequence, O’Hara is heard saying that he is not interested in “movies … as a substitute for poetry”[15]: his statement is particularly interesting in relation to Moore’s own art. I would argue that for Moore, film is an extension of poetry. Shortly after O’Hara’s expression of his cinematographic interests, Moore’s narration resumes: “One of the poems in Frank O’Hara’s book Meditations in an Emergency, published in 1957 by Grove Press, is titled ‘To the Film Industry in Crisis,’ and in part the film script that O’Hara is writing with Alfred Leslie is derived from this poem.” I see Moore’s documentary as being derived from O’Hara and Leslie’s film script, which is itself derived from the poem: film as extension of poetic content. And once Moore has shown what he can do with Leslie and O’Hara’s script read aloud, he goes back to O’Hara reading from the page in the studio, back to O’Hara typing words on his typewriter, back to the materiality of the word and to the origin of it all: writing.

In the same sequence, there is the famous scene where, in the midst of typing a sentence inspired by his discussion with Leslie, O’Hara receives a telephone call from one Jim. O’Hara picks up the phone and, after greeting his friend, the scene continues:

O’Hara: This is a very peculiar situation because while I’m talking to you, I’m being filmed for educational TV, can you imagine that? … Yeah. Alfred Leslie is holding my hand while it’s happening. It’s known as performance. … What? Fleshing bolt, what does that mean? … Flashing bolt, you mean.

Leslie: Write it in!

O’Hara: Oh good! Flashing bolt, very good. A fla-shing bolt. Is that art or or what is it? I just laid it onto the paper.

The passage reveals a movement from metapoetics to telepoetics: Moore’s documentary is not only about the writing of a film being made in the middle of a community (O’Hara holds Leslie’s hand, receives a telephone call). In spite of Moore’s reverence for writing, he insists on the possibilities afforded by film, by the combination of images and sound, and, above all, by the possibility of broadcast. There are two equally important “tele” in this passage. One, the telephone, is the emitter: O’Hara receives a phone call, and the voice at the other end of the line provides him with a word that finds its way into the script. The other one, the television viewer, is the receiver: the viewer is watching the film, i.e., the word going from the telephone voice to O’Hara to the page. Moore tells us that film is not only animation, but also broadcasting and distribution. By staging O’Hara receiving a phone call, Moore mirrors and acknowledges the position of the viewer receiving the film (and the phone call). Moore’s documentaries are not only about poets writing, they are also about poetry as circulation and communication, poetry as a system of information and transmission. In that respect, he uses the documentary to extend the conversation about poetry (meta) and to extend the reach of poetry as conversation (tele). The TV viewer cannot hold Leslie’s hand. However, for lack of physical contact, film offers a form of connection, if the viewer is willing to take it up: we are invited to continue the discussion, to place another phone call, make another film, write in another word, extend what O’Hara was calling

a tremendous poetry nervous system

which keeps sending messages along the wireless luxuriance

of distraught experiences and hysterical desires so to keep things humming

and have nothing go off the trackless tracks[16]

Moore’s documentaries hope to do that precisely: to keep sending the messages of poetry along the wireless luxuriance of TV networks, and, nowadays, the internet.

On several occasions in the documentary series, Moore discreetly reveals his hope that his films be not secondary, but rather contiguous and continuous to the poetry they document. Moore’s ambition, I believe, was to use his films to facilitate the circulation of poetry; his hope was that his documentaries would spur viewers on to write. At the beginning of the episode devoted to her, Sexton confesses having gone through a nervous breakdown, which prompted her to see a psychiatrist:

My psychiatrist suggested that I watch channel 2. “You have an educational television there. So won’t you look at it.” So I did, and I. A. Richards was explaining the form of the sonnet and I thought “Oh, that’s a sonnet” so I sat down and tried to write one, it was pretty bad then, and that just turned me on, and then I turned on and wrote like mad … working and working and working on a poem that was no good of course, but you know, I had to learn that way.

The “educational” in the NET series title acquires a new meaning: the person being educated is not only the viewer but also, the poet. And I would argue that Moore’s films do not only offer an education to poetry but also suggest a conception of poetry as education. The Sexton documentary is a film about learning how to write, and if Sexton managed to do so by watching TV, so can the viewer. There lies the implicitly democratic ambition of the film: to spread the desire for poetry by saying that it is possible to become a poet, that it is a matter of culture and education, of time and work, and that the poet we are watching was in the same position as the viewer. Moore has not lost sight of the etymology of “educational,” to bring up, to elevate, to lead out. At the same time as Sexton explains how she started writing poetry, one is watching an educational film about poetry, one also becomes part of the poetic chain. Moore made a film about a poet becoming a poet watching a film: instead of being between two pages, the writing is between two films, and ultimately between two or several poets: I. A. Richards; Anne Sexton; Richard Moore; the viewer.

3. Moore’s talking pictures

3.1 The resistance of voice

In his documentary, Whalen says he likes “reading [aloud] to test out poetry.” The difference between a sound recording and a film is that with video, the test of poetry is also a test of the poet’s physical presence in front of the camera. Such presences greatly vary in Moore’s films from Olson’s and Ginsberg’s own theatricalities, if not to say eccentricities, to the more restrained readings of Snyder (standing up) or of Merwin and Lowell (both sitting — an interesting detail for poets who are said to be among “the most distinguished”). In Snyder’s case, although the setting of his reading is extremely sober, his face becomes a small theatre of physical expression, so that there is a test of physical presence. In Merwin’s and Lowell’s cases, the analyses and talk they provide before their readings take on some kind of physical engagement, if not animation.

In June 2003, the Double Change collective invited Bernard Heidsieck to give a reading in Paris with sound poet and composer David Christoffel. Heidsieck’s performance, “Breathings and Brief Encounters,” was composed of the side and background noises of poets’ recorded readings, the sounds they make before speaking: mouth, lip, and tongue noises, glasses poured and drunk, and all other collateral sound incidents. I would like to keep in mind this performance for the following remarks. The difference between Heidsieck’s piece and Moore’s films’ soundscapes is that the bodies producing the sounds could only be imagined in Hiedsieck’s sound performance. In the films, however, the poets are visible. This is a crucial difference as Moore plays on the interaction between sound and image, drawing attention to the sound sources with the use of various cinematographic techniques, including zooming in.

At the end of an animated discussion on poetry, nature, and science, where Olson quotes his “great master Whitehead,” he then pauses, takes a deep breath and drags on his cigarette. As he does so, the camera — which has lost nothing of Olson’s gesticulations — zooms in on the poet’s face as he is about to exhale the cigarette smoke: instead of letting us hear the sound of Olson’s breath, Moore immediately juxtaposes footage of a ship tooting its horn off the coast of Gloucester, so that one has the impression that instead of exhaling Olson is producing the startling sound.

Far from being disrespectful, this sequence, I would argue, is Moore’s nod to Olson’s projective verse. What the tooting sound does is invite the viewer to pay attention to the sound quality of Moore’s films, as noises, silences, breathings are crucial elements of the lives and portraits of the poets. The incredible grain of Olson’s voice, his heavy breathing, are shown to be continuous with the sound of the local ship, with the geography and materiality of Gloucester. This almost comic detail of Moore’s film is, I believe, a great homage to the greater-than-life personality of the poet and, more generally, to his aesthetics.

Video images have such immediate influence on the viewer that it is sometimes easy to neglect their sound dimensions. Moore never forgets that film is image as well as sound: his deft use of their interaction allows him to pack a lot of information about the poets into a mere fifteen- or thirty-minute program. When Robert Creeley, sitting in his kitchen with his wife, ponders upon “a resistance” he struggles with, “which is so complex [he] never understood what it actually was proposing, something [which] questions the possibility of any statement,” he reminisces, laughing, how his family was highly verbal and articulate, and how the women in his family were voluble. Creeley continues talking in the midst of laughter and smoking, a rich and lively sound sequence. This is followed by a reading of “Le Fou” in which Creeley’s voice, so joyful and forthcoming a minute before, is now vibrating, as if hesitating, giving the impression of being on the brink of collapse, as if it were embodying this resistance, this almost painful attempt to make any statement possible, as if the voice itself were writing the poem. Moore makes this resistance almost physical in the soundtrack to the film, as Creeley puts a cigarette in his mouth, starts talking about the poem, mentioning its dedication to Olson, lights up his cigarette, and, as he inhales deeply, starts reading.

The vibrato of Creeley’s voice brings out in the film the materiality of language. This is precisely what Moore never forgets; his film reveals and captures what Ann Lauterbach calls “the slight curb between written and spoken”:

Robert Creeley, famously, slight curb between written and spoken; this often the only way you could know or discern that the poem had begun as he reminisced about this and that: the minute shifts in cadence, pace, inflection; voice the insignia of poetic affect. Intensity spread out or distributed across or into the ordinary, a kind of diction, vernacular, what can be spoken I think Pound commanded (and did not follow).[17]

3.2 Making a sound like this

The materiality of sound and speech is not located only in the voice of the poet; listening to Heitor Villa-Lobos’s Bachianas Brasileiras suite number 5, Sexton launches into a regretful meditation:

I can’t make a sound like this … this is totally quacked … and crazy as it is … listen to that voice … and with those clumsy words I must try to make a … I can’t … that’s almost like a flute you know or a songbird or a … I don’t mean to sound … it’s the way I feel really inside … silly … I mean I feel ashamed of it even … and this damned typewriter, all it gives me is words, they don’t do that to me, they don’t make me cry the way that does makes me cry … like something I’ve lost … there’s something in that that I’ve lost and that I can’t find …

This sequence combines the singing voice of Villa-Lobos’s suite, Sexton’s ruminations, and the clatter of the reluctant typewriter. With such sound mixing, this moment becomes a sound poem of its own, at the very same time that Sexton expresses the impossibility of being as moving in writing as the singing voice. Moore seems to prove her right when he abruptly follows this scene by the rather sober and somber reading by Sexton of her poem “The Addict.” However, Sexton’s “all it gives me is words” is proven wrong: words are certainly insufficient in some situations, but they are and do already a lot, as Sexton’s lively readings in the documentary, sometimes at odds with the dark confessional nature of her poetry, confirm.

Besides, words are not necessarily at odds with music, as Ed Sanders and his group the Fugs show: their aesthetic and political mission, Sanders says, is to “present literary rock ’n’ roll” to the American public. At the time that Moore shot his documentary, Sanders, one of the youngest poets of the USA: Poetry series (he was twenty-six), was one of the poetical and political agitators of the Lower East Side, running the literary, cultural, and pacifist community center known as the Peace Eye Bookstore. In Moore’s sequence on Sanders, the talking pictures become singing pictures.

Several reading modes are juxtaposed as words are given a variety of sonic dimensions. Sanders is first shot sideways, sitting on a chair and reading the poem “Cemetery Hill”: at first calm, his reading becomes more rhythmical and agitated as the camera zooms in on the poet’s face. The reading is followed by a final passage in which Moore manages to capture the different states and sounds of the poet’s voice singing accompanied by the Fugs at the Astor Playhouse. Moore’s sound editor, Stanley Kronquest, manages to turn this final moment into a polyphonic sequence made of a great variety of sounds and speaking modes: an interview with the poet, background music, Sanders’s exchanges with his musician friends, and Sanders singing “I Want to Know,” followed by a blues improvisation, which is at once burlesque poem and public address. In the following transcription of that passage, I have indicated speech and sound status to underline Moore’s and Kronquest’s art of sound montage as well as their skill at handling a variety of elocution modes:

[Sanders is on stage at the Astor Playhouse, with band. Soundtrack: Ed Sanders interview added in the postproduction phase.] We want to present literary rock ’n’ roll, for instance we have a song called “I saw the best minds of my generation rock” which is Allen Ginsberg’s very wonderful poem edited into highly precise rock genre. We have … our first 45 release has on its flip side a poem by Charles Olson from “Maximus, from Dogtown” … [On stage: the musicians shout. Sanders sings. Direct sound.] Let’s do it, Charles Olson’s famous … “We drink / Or break open / Our veins / Solely to know / Solely to know / Solely to know // Hunger / Drives me onward / To feel / All of the skin / All of the skin / All of the skin // The thrill / Of the knowing / Has me / Out of my brain / I want to know / I want to know” … [Soundtrack: Ed Sanders interview added in the postproduction phase.] You can’t sell out, we have to sing our songs, we have to write our poetry. [Sanders’s blues improvisation. Direct sound.] “You find a copy of The New American Poetry right in your chest of drawers … and she only want to make love to Robert Duncan! She only want to flirt with Charles Olson too! What come over you baby?” [Soundtrack: Ed Sanders interview added in the postproduction phase.] If we don’t proceed forward and talk and speak and think and act the way we want to, then our children will scorn us. [Sanders addressing public. Direct sound.] Do you feel it? Do you, do you?

The lyrics of “I Want to Know” come in part from Charles Olson’s “Maximus, from Dogtown.” Whereas Sexton felt sorry not to be able to sing with her typewriter, Sanders shows that he is capable of singing other people’s poems and borrowing their lines for his songs: there is continuity between writing and singing, between poems and songs. As audiovisual archive, Moore’s documentary juxtaposes the voice that explains and the voice that sings (as well as other voices and sounds), the voice that sings a preexisting text — itself inspired by Olson’s poem — and the improvising voice that invents the text as it goes along.

3.3 “Sounds, rather than words …”

Even when words are no longer words but “consist of sounds rather than words in the conventional sense,” as in Michael McClure’s reading from Ghost Tantras, Moore finds ways to supply images not as a means to illustrate words but to give them additional relief, possible extensions in the visual world. To do so, he explores the Hell’s Angels poster behind McClure, zooming in on a plane, a billow of smoke, two faces, never staying too long, lest the images would force meaning on the sounds. Moore’s documentaries are tests of poetry because they are first and foremost tests of themselves as sound and visual poems, constantly reinventing themselves in the service of poets and poems.

The transition between the sequence on McClure and the sequence on Brother Antoninus within the same program shows that for Moore each poetical oeuvre deserved a specific cinematographic treatment: this specificity is Moore’s answer to the aesthetic of each poet, the filmmaker’s translation in images and sounds of each poet’s particular poetics. I have transcribed below the very end of the sequence on Michael McClure and the abrupt transition to Brother Antoninus.

Narrator: Michael McClure once wrote: “Poetry is a muscular principle. There is no logic but sequences of feeling. My viewpoint is egocentric. Self-dramatization is part of a means to believe in spirit.”

Michael McClure: I once made poetry that was … that did not have images in the sense of what Shelley called mimetic image … in the sense that where the image describes something in the real world, but in the sense where the sound of the poetry itself created an image in the mind, in the body, in the muscles of the body, and it created a melody that was also an image that imprinted itself in the body physically.

[Scene in the zoo with the lions begins. McClure comments continue.]

Whether it does, whether it truly does it, so that it’s an experiment, and an attempt to do it. And then I went to read it to animals, I suppose because they’re simpler cousins.

SILENCE THE EYES! BECALM THE SENSES!

Drive drooor from the fresh repugnance, thou whole,

thou feeling creature. Live not for others but affect thyself

from thy enhanced interior — believing what thou carry.

Thy trillionic multitude of grahh, vhooshes, and silences.

Oh you are heavier and dimmer than you know

and more solid and full of pleasure.

Grahhr! Grahhhr! Ghrahhhrrr! Ghrahhr. Grahhrrr.

Grahhr-grahhhhrr! Grahhr. Gahrahhrr Ghrahhhrrrr.

Gharrrrr. Ghrahhr! Ghrarrrrr. Ghanrrr. Ghrahhhrr.

Ghrahhrr. Ghrahr. Grahhr. Grahharrr. Grahhrr.

Grahhhhr. Grahhhr. Gahar. Ghmhhr. Grahhr. Grahhr.

Ghrahhr. Grahhhr. Grahhr. Gratharrr! Grahhr.

Ghrahrr. Ghraaaaaaahrr. Grhar. Ghhrarrr! Grahhrr.

Ghrahrr. Gharr! Ghrahhhhr. Grahhrr. Ghraherrr.[18]

[McClure sequence ends. No transition. From above, we see Brother Antoninus sitting on a bench in the monastery garden.]

Narrator: The contrast is absolute between the lion house and the monastery at Saint Albert’s college in Oakland, California, where Brother Antoninus lives for twelve years.

When McClure insists on the sonic dimension of poetry, wishing that the melody of the poem would imprint the body physically, Moore fulfills this wish by shooting a scene in which sound seems to become material, the words of “Tantra 49” turning into cries, the camera coming and going between the poet’s body and the lions, zooming in and out, filming from below, lingering on McClure’s leonine mane, the lion’s roar answering the poet’s lines and cries. By coming so close to the lions’ and the poet’s bodies, materializing their conversations and echoes, the filmmaker fulfills McClure’s wish to establish a continuity between animal and human. Everything would have been quite different had Moore produced a static and distant recording of the scene; on the contrary, Moore’s camera offers physical engagement, the sound dimension of which is essential for the viewers whom sounds reach and mark. Moore’s documentary embodies McClure’s “melody of poetry.” When at the end of this sequence Moore leads us away from McClure’s polyphonic zoo to take us abruptly to Brother Antoninus’s monastery garden, the narrator remarks with humor that “the contrast is absolute between the lion house and the monastery at Saint Albert’s college in Oakland, California, where Brother Antoninus lives for twelve years.” Camera movements and sound editing embrace the sobriety of the monastery. The documentary juxtaposes two radically different bodies of work, from McClure’s ecstatic howling to the severity of Brother Antoninus’s sermons, from the lion’s roars to the threatening silences of the monastery.

Conclusion: presenting poetry

Although coproduced by the San Francisco public television channel KQED and National Educational Television (NET, created in 1954 and “replaced” by PBS in 1970), the Poetry: USA series films are by no means didactic. They do have an educational value, even if they cannot be called pedagogical as that term applies to educational television programs of the 1950s and 1960s.[19] By choosing to make documentaries mostly on experimental poets (with the exception of Lowell, Wilbur, and Sexton), and by refraining from asking poets to explain or close-read their poems on television, Moore chose to present poets and poetry rather than impose textual analysis on the viewer.[20]

To make poetry present to the greater public was more than necessary in 1966: it was not always easy to find books by Moore’s poets in libraries or bookstores. In 1966, one had to live in a fairly large city on the east or west coast to find access to their works. By focusing on readings by the poets, the films therefore provided national access to a poetic corpus. Presenting poetry for Moore also meant presenting the poets personally, almost intimately. Thanks to the camera’s proximity to its subjects, the viewer is invited to step into the poets’ homes. The television screen is not so much a fourth wall as a breach of the proverbial ivory tower. Moore attempted to create a mirror effect in his documentaries, suggesting that poetry is not only accessible but also a possible form of art which one can try: didn’t Sexton decide to start writing sonnets after watching I. A. Richards’s educational program on channel 2?

Still from I. A. Richards’s “Sense of Poetry” lectures, WGBH-TV (1957).

Moore’s documentaries represent an approach to poetry completely different from Richards’s solemn “Sense of Poetry” lectures on WGBH-TV in 1957[21]: by letting the poets speak for themselves and their works, Moore extended poetry and made it available to all. It would be tempting to see Moore’s documentaries as a response to what Mark Garrett Cooper and John Marx call “New Critical Television,” just as Donald Allen’s 1960 anthology The New American Poetry, which provided Moore with so many of his poets, was a response to Donald Hall, Robert Pack, and Louis Simpson’s 1957 The New Poets of England and America. What is certain is that Moore’s documentaries translated into cinematographic terms some of the principles of Allen’s anthology: experiment, process, and openness.

Although Moore’s films were broadcast nationally only in 1966, they continued to circulate, especially in the 1980s onwards as VHS tapes were copied from the original recordings kept at the Poetry Center of San Francisco State University and elsewhere.[22] That the films should have continued to circulate after their television broadcast, albeit within a small community of poets and poetry aficionados, speaks volumes about their intellectual and educational value. One learns from Moore’s documentaries by spending time with the poets, hearing them read, and discovering how the body of the text becomes the body of the poet in the temporality of the reading. One also learns from Moore’s art of montage: the documentaries are provocative as well as inviting, as his camera always suggests and opens up new possibilities of reading, seeing, and hearing poetry.

National Educational Television logo, 1960s.

1. As Cedar Sigo, quoted by Garrett Caples, writes: “What I find most commendable about the USA: Poetry series is Richard’s choice to showcase so many heroes of the queer underground and without a trace of tokenism. His mindset dates extremely well. One would be hard pressed to find another man so unencumbered by social divisions. Richard is humble in person but his work and what it attempts are fierce, almost dangerous dreams.” Garrett Caples extends this remark to Moore’s films on African Americans and social and political revolutionaries: “[Moore] had a clear predilection for the underdog and a commitment to social justice that amounted to a passion.” See Garrett Caples, “Homage to Richard O. Moore (1920–2015),” City Lights Blog, March 26, 2016.

2. Caples, “Homage to Richard O. Moore.”

3. Caples, “Homage to Richard O. Moore.”

4. The thirteen films directed by Richard O. Moore in the USA: Poetry series are: program #2: Allen Ginsberg and Lawrence Ferlinghetti, broadcast March 6, 1966; program #3: Robert Duncan and John Wieners, broadcast March 13, 1966; program #4: Gary Snyder and Philip Whalen, broadcast March 20, 1966; program #5: Brother Antoninus and Michael McClure, broadcast March 27, 1966; program #6: Theodore Roethke, broadcast April 3, 1966; program #7: Anne Sexton, broadcast July 31, 1966; program #8: Richard Wilbur and Robert Lowell, broadcast August 7, 1966; program #9: Louis Zukofsky, broadcast August 14, 1966; program #10: Kenneth Koch and John Ashbery, broadcast August 21, 1966; program #11: Frank O’Hara and Ed Sanders, broadcast August 28, 1966; program #12: Denise Levertov and Charles Olson, broadcast September 4, 1966; program #13: Robert Creeley, broadcast September 11, 1966; program #14: “In Search of Hart Crane,” broadcast September 18, 1966.

5. Those questions included: “We invite speakers to reflect on the production, preservation, and uses of audiovisual archives of poetry. What status should be given to sound recordings? Are they works in their own rights or documentation? What is the difference between an audio recording and a video recording?”

6. According to the Online Etymology Dictionary, the word document dates back to the early fifteenth century to mean “teaching, instruction”; to Old French meaning “lesson, written evidence”; from the Latin, documentum, or “example, proof, lesson”; to Medieval Latin, meaning “official written instrument”; from docere, “to show, teach, cause to know”; originally, “make to appear right”; causative of decere, “be seemly, fitting”; from the PIE root *dek-, “to take, accept.”

7. Pierre Michon, “Les deux corps du roi,” in Corps du roi (Paris: Verdier, 2002), 13–14.

8. “Meta,” Online Etymology Dictionary.

9. Charles Bernstein, “What Makes a Poem a Poem.”

10. From the Latin confrontare: front, forehead, face.

11. John Wieners, “A Poem for Painters,” in Selected Poems, 1958–1984 (Santa Barbara, CA: Black Sparrow Press, 1998), 29.

12. “Flaubert affecta de n’avoir rien de tout cela [une vie personnelle], cela qu’il avait, et cette affectation lui devint une réalité; il se bricola un masque qui lui fait la peau et avec lequel il écrivit des livres; le masque lui avait si bien collé à la peau que quand peut-être il voulut le retirer il ne trouva plus sous sa main qu’un mélange ineffable de chair et de carton-pâte sous la grosse moustache de clown. Pourtant ce n’était pas vraiment le clown qu’il faisait — il faisait le moine.” Pierre Michon, “Corps de bois,” 20–21.

13. “Intimate,” Online Etymology Dictionary.

14. Frank O’Hara, “Having a Coke with You,” in The Collected Poems of Frank O’Hara, ed. Donald Allen (New York: Knopf, 1995), 360.

15. O’Hara: “The reason I’m interested in movies is not as a substitute for poetry but who’s making it. If Al’s making it, then I’m interested in the sense that I’m going to understand what it’s going to be or that at least I know that it’s going to be something interesting for me.”