Wonky structures

On Alice Burdick's 'Book of Short Sentences'

Book of Short Sentences

Book of Short Sentences

There is no private life which has not been determined by a wider public life. — George Eliot[1]

Maybe Alice Burdick was beginning to get very tired. I don’t know. But the next to last poem in Book of Short Sentences is unlike anything else she’s ever published. The poem, “Don’t Forget,” is direct, uninhibited, and visceral. Burdick’s voice is emboldened by a sense of emergency (social, political, and ecological) that she feels in her body’s hotheaded cells. Like Daniel Jones’s “Things That I Have Put in My Asshole” or David McGimpsey’s “O Coconut,” Burdick’s “Don’t Forget” is — thanks to its pinch of salty iconoclasm — destined for iconic status in Canadian letters.

The poem pivots on the eponymous two-word phrase. Burdick reminds herself as much as she does you and me: “Don’t forget.” It’s a command, an ethical imperative, one that both admonishes and pleads. The veteran poet doesn’t write “I remember.” This ain’t Proust or Joe Brainard or, thank heavens, Mary Ruefle. There’s a difference. “I remember” is the soft-focus lens of dream sequences, film noir, and Skinemax, while “Don’t Forget” is the hard fact of living and loving and surviving. Every orifice, awkward position, innocent caress, erotic sound (e.g., the battery-charged hum of the vibrator), and bodily fluid (cum, piss, blood) is clear and present. It’s a poem drenched in “the juice / that rises, that runs.”[2] “Don’t Forget” is uninterested in the cleanliness of nostalgia and fantasy.

Burdick or her “speaker” — the poem huffs and puffs and blows the difference between the two down — gives an account of her sexual history. She’s not naming names, though. This is neither an exposé for a sleazy tabloid nor the pules of a jilted lover in a glossy CanPo zine. The poem is not an anything-you-can-do-I-can-do-better brag. Graphic, sure; gratuitous, never. For a poem with so much fucking, it’s disarmingly sweet. The poem is not strictly autobiographical, that is, a sexual bildung with a beginning, middle, and end. Rather, it’s an ad hoc inventory of how the body archives the “imprint” of desire (121).

She has young lovers (“Don’t forget the rabbity / unsatisfying fucks with younger men” [123]) and old lovers (“Don’t forget being the alien trophy — shining, / erotic, young” [122]), mostly men, but also women. At times, she’s given up sex, opting for abstinence that’s supplemented by “instruments of pleasure” (123). Sex feels different after medical operations, too: “Don’t forget fucking while stiches healed, moving with caution. / Don’t forget the way things changed” (122), writes Burdick. With grace, she even tells of her first sexual encounter after the death of a previous boyfriend. She refers to it as “the rescue fuck / that brought me back to my body” (121). There’s a first for almost anything. If you can think it, it’s probably in the poem.

Despite its Boschian scope, the poem ends on a wistful note: “So much world in these bodies. / Don’t forget to remember the world / in our bodies” (123). Sex is simply the conceit through which she makes her point that the body stores and retrieves Whitmanesque multitudes of feelings and meanings, good and bad. It’s our trusty guide as we move into an increasingly volatile, militarized, and technodetermined future. Don’t forget “the odd inescapable pleasure of anal”-ogue and the immense intimacy of two “joined bodies” (121).

“Don’t Forget” is great. That’s why I begin with it. But it’s not exactly representative, in style, of Burdick’s poetry. It’s been twenty-five years since Burdick’s precocious debut, Voice of Interpreter (1991), a chapbook published by poet Victor Coleman’s The Eternal Network when Burdick was only twenty-one. Since then, she’s published four full-length collections, including Simple Master and Holler, as well as multiple chapbooks, including Signs Like This, Fun Venue, and The Human About Us. In 1995, Clint Burnham devoted an entire issue of his zine CB to Burdick’s poetry. Over the years, she’s written excellent poems — “Nostrum,” “Fact,” “Vatican Degree,” and “Covered” immediately come to mind — in the tradition of what poet-critic Rachel Blau DuPlessis calls “the analytic lyric,”[3] her spin on Ezra Pound’s logopoeia, “a dance of the intelligence among words and ideas and modification of ideas and characters.”[4]

Now, Pound first used the term logopoiea in 1918. Ever the carnival barker, Pound, in his review of Others (1917), was talking up the cool, detached wit and irony of modern poets Mina Loy and Marianne Moore.[5] Logopoeia is, put simply, the language of brinksmanship. It pushes sense dangerously close to the edge of nonsense. Logopoeia is, as a result, difficult. Furthermore, logopoeia doesn’t translate very well into the plastic arts or music. Heck, it downright vilifies the musical phrase or visual description. It’s more cerebral. It takes place in language rather than, say, in the Valley of Chamonix. DuPlessis revises Pound’s definition, connecting Loy’s and Moore’s poetic strategies to the radical feminism of the New Woman. Thus, DuPlessis’s analytic lyric relocates Pound’s logopoeia to the realm of ideology. Abstract diction, inverted syntax, puns, mixed metaphors, clichés, cartoonish tone, surreal images, and citations are placed in the service of social analysis. Not surprisingly, it’s almost always antisentimental and often (but not exclusively) satirical. It’s a lyric mode that scoffs at preciousness.

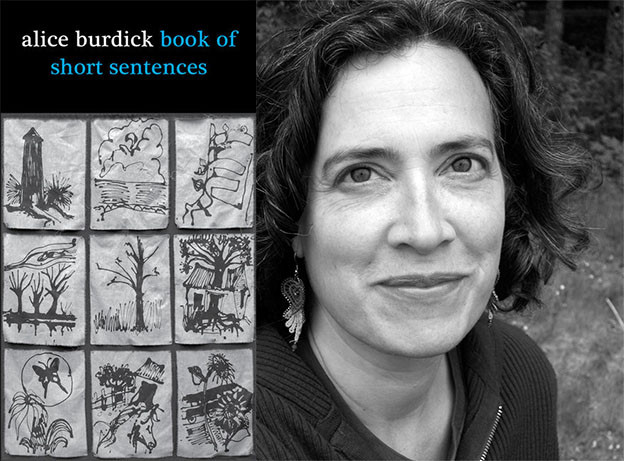

Burdick’s “Covered,” from 1994, is an excellent illustration of what I’ve just described. The poem is, first and foremost, an elegy for Burdick’s mother, the artist Mary Paisley, whose artwork, incidentally, graces the cover of Book of Short Sentences — a batik titled “Land of Heart’s Desire.” Burdick grieves, of course. But the weeping and wailing à la Shelley’s “Adonais” is severely muted. She doesn’t retroactively bowdlerize Paisley’s life. Burdick connects her private act of mourning with more pressing public concerns, notably deforestation in British Columbia, Canada’s history of colonialism, and sexism in Toronto’s literary community of the early to mid 1990s:

Everybody shits, small and big. Even when

you know everything, you still shit. This we share.

Spread it around, larger serving. ‘Nice hairstyle.’

It’s not a cut. When a man goes to a tree

and cuts it down, paid, there’s a way.

One cut up: degrees. One cut down: angles.

A piece comes out and the tree falls. That’s how

to take something down. You must watch

for the shadow, or you’re under.[6]

I can’t think of another Canadian poet brazenly French enough, then or now, to inject scatology-based satire into an elegy for one’s mother. Logopoeia lends itself to this sort of irreverence.

The idiomatic echoes, mondegreens, puns, and other verbal hijinx are all on display in Book of Short Sentences. In “Resolutions,” Burdick simultaneously skewers marriage and the managerial class: “Fire me now / or forever hold your peace. / Fantastic manager of dead ideas, / you can’t make me obey” (42). “Cover for Evie” is a homophonic mistranslation of one of Theocritus’s epigrams. His version begins, “This bank makes welcome citizen and foreigner.” Burdick filters her translation through the 2008 financial crisis and subsequent Age of Austerity: “This bank’s an unwelcome citizen, foreign / to depositions by the withdrawn” (66).

But her style’s at its finest in a longer poem like “Travelling Poem — Pittsburgh.” “Travelling Poem — Pittsburgh” is not as raw, sexy, or obviously winning as something like “Don’t Forget.” But it’s the major achievement, thus far, of Burdick’s career.

Now, a lesser Canadian poet than Burdick visits Pittsburgh and describes a ride on one of the city’s two funicular railways, the Duquesne and Monongahela Inclines; or, a trip to the Andy Warhol Museum on Sandusky Street; or, a morning jog through Schenley Park; or taking in a Pittsburgh Pirates game in PNC Park while memorializing the days of ol’ Three Rivers Stadium. Passages of concrete description, with the occasional metaphoric flourish, help visualize the city. A historical reference or two to the golden age of the Rust Belt: Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Buffalo. Some local color cuisine. The language as instrumental and inspired as a Baedeker’s. The lesser poet is predictable, self-congratulatory, and obnoxiously moral. Destination is nothing more than a cipher for the poet’s aggrandized sense of vocation.

In the case of Burdick’s “Travelling Poem — Pittsburgh,” however, there’s not a single reference to the city beyond the poem’s title. Burdick focuses on the constellation of structures — airports, security checkpoints, planes, hotels, elevators, tourist traps, amusement parks, nature trails, queues, and touchscreens — that mediate the precarious relationship between private and public life during travel. The airport gate is filled with “People asleep in their purgatories, / taking up all the available seats”(48). At the park, “Nature trails loop where there used to be / nature. Now it’s just corporate interest” (49–50). Repeatable, monetized experience is naturalized. The vending machine at the hotel is broken: “The dream / of order is out of order / as usual. It’s pernicious” (50). Burdick has trouble reading directional signs, leading her to announce, in exasperation (and cleverly confused pronouns), “The misdirected continue on their way, our way, / it doesn’t matter” (48). In a short essay from 2002, Burdick explains that “the world of structures is pretty wonky; the buildings I walk into and ride up and down; the media I gorge on that leaves me hungry in ignorance. Not to say that there is not beauty in all this.”[7]

Her metaphors refuse to serve purely descriptive ends. After all, poetry’s got to be more than a glossy picture postcard that reads Welcome to Pittsburgh in bright yellow cursive, right? Very rarely do Burdick’s metaphors rely on visual contiguity because, as she notes, “The visual / is not always proof of existence, / or movement” (47). Planes, for example, are “transoms of the sky”; the sunset seen from a window seat is compared with an “orange [kitchen] sink”; and the exit door is “enjambed” (47–48). Like those of the late great Peter Culley, Burdick’s metaphors behave like critiques of value. A poetics of precariousness. For example, she writes, “Far from the fallow fields, the glow / of the privileged subset, the extremely groomed, / impeccably pressed, in fact almost 2-D” (48). She uses a pun (“pressed”) plus catachresis (“pressed” and “dressed”) to create the metaphoric correspondence between style and substance, the latter of which is missing. Preened free of his flaws, the thin man is less human but such a state of existence definitely has its perks: seat “2-D” is first class on the plane. The “fallow fields” are beneath and behind him — in economy class.

Burdick announces in the same poem, “Let’s take a minute for ephemera” (49), those small, seemingly inconsequential things that come and go but which bond social beings together. Chance encounters (“voices from the past”), background music (“a Prince soundtrack”), or “a yawn from an official uniform” (49). Burdick understands ephemera, figuratively, to be like shared germs in a poorly ventilated airplane: “Air composed of inflamed nostrils, invisibly angry / sinus tissue. That’s what you breathe through / the majesty of the celestial dome” (49). She’s also committed to listening to the world, not staring stupidly at it. “Fight with your ears too,” she says, “Believe them / for a change. Sounds mean what they say, / beyond words” (49). “Believe them” recalls the #Ibelievesurvivors campaign in the aftermath of the Jian Ghomeshi trial. Burdick is making the case for the evidentiary truth of (gendered) feelings that are nondiscursive.

By comparison, consider Karen Solie, a much-lauded Canadian poet and contemporary of Burdick’s. Solie’s poem “Erie” describes a couple’s getaway to the shores of Elgin County in the wintertime — what she calls “the cheap side / of shoulder season.”[8] Solie populates her poem with plenty of local color, including the cuisine (perch), birds (harriers), and buildings (“dopey dance clubs”).[9] Hawk Hill, Port Burwell, Tillsonburg — gritty authenticity in those CBC-approved name drops. Lake Erie is polluted: the couple learns of a “dead zone / in the central Erie basin,” the result of “phosphorous runoff” from nearby sewage treatment plants.[10] Wind turbines are a wonderful source of alternative energy, yes, but they’ve also increased “avian mortality” in the area.[11] Plus, local Eeyores consider them eyesores, braying about them over smokes: “the eternal / complaints of the People” — a condescending capitalization, if ever there was one.[12] Solie ironically describes the turbines as “minimalist daisies”[13] (a brutalist metaphor). Her objective correlative for the region’s absent middle class is the scale of housing: “grim mansions / of unprincipled dimensions and small / structurally iffy houses whose junk fell / over itself joyfully down the creekbanks.”[14] In short, everything is contaminated, including the very couple that walks and drives and, most importantly, argues its way through the empty beach resorts and port cities. Pathetic fallacy. Will they, won’t they projected onto the scenery. “Erie” is as much a poem of the late nineteenth century as the twenty-first, which is probably why it’s so commendable to many readers.

At this point, I should say that Burdick’s analytic lyric has three features that distinguish it from traditional logopoeia. First, Burdick is steeped in the tradition of Dada and Surrealism as well as first and second generations of New York School poetry. So, she’s a-okay with a degree of white noise, balderdash, and marvelous imagery.

Every time I hear ‘rabbit,’

I think fridge. (88)

or

Handlebar bikes under noses. (32)

or

I bawl

eyeballs

and the tentacles climb

from empty space, dragging

what might be a soul,

or just a slimy sock, out into the sunshine. (24)

Such moments establish a poetic kinship with the likes of Barbara Guest, Bernadette Mayer, and Alice Notley more so than Phyllis Webb, Daphne Marlatt, or Margaret Atwood. It also explains Burdick’s inclusion in Stuart Ross’s landmark anthology, Surreal Estate: Thirteen Canadian Poets Under the Influence. Second, Burdick believes sincerely in the occult and paranormal: ghosts, spirits, aliens, and other invisible and unnamable forces. In “The Great Outdoors,” for example, she looks out over a pasture to see “oxen / and aliens.” A delicate rhyme of natural and supernatural phenomena (16).

Third, over the years, Burdick’s tone has become increasingly casual. Deceptively so. Easy, understated, well-worn diction — that homespun idiom of Nova Scotia. Global warming and coastal erosion: “nature stuff,” she calls it (117). No biggie. “Bully for You” begins, “Everything takes forever, / especially time.” In “Heart Bump” — the closest Burdick’s ever gotten to a love sonnet — she describes the heart as “this thing / that sits and thumps … / and does other stuff too”:

like throb and burn,

and makes us wonder

which way the blood pumps —

the constant bump

of corpuscles through muscles,

from one end to the other.

It makes us wonder,

do we feel it and know when

it’s made its last jolt? (23)

Gone are the angular mannerisms of Loy’s moon or Moore’s fish. Burdick’s plain talking lulls you, then suddenly and unexpectedly you find yourself dwarfed by her giant ideas, and the fate of mankind, it turns out, depends on finding out what follows grammatically from an easy-breezy phrase like “I was thinking about bathtubs” (53).

That’s how “Distraction Poem” starts, by the way. “I was thinking about bathtubs, / because I was in one” — from the get-go, there’s a mind-body split. She’s in the tub, and she’s thinking about tubs. She proceeds to watch a YouTube video (see and hear how “tub” becomes “tube”), take a phone call (“it wasn’t for me”), read her private journal, check Facebook (“how many people like me / or don’t, according to a thumbs-up icon”), reflect on her insecurities with “rolled back eyeballs,” shed skin cells “at a visible and molecular level,” hiss disapprovingly at her “jerk” of a cat, and, in a Zen twist, “[forget] about the bathtubs” altogether — that is, the one she’s in and the one she was thinking about in the first place (53). If “Don’t Forget” is organized by the affective force of sexual desire, then “Distraction Poem” is organized by the rhythm of consciousness as it repeatedly disperses and gathers itself. The poem’s fast turns and loops recall Drift-era Kevin Connolly, though Burdick’s language is far less self-consciously literary than his. Her poem hums along without much fuss.

In the four-line finale, the pleasure and stress of distraction are redoubled by the arrival of loud, boisterous children: “The kids came home and started yelling, / each shriek translating to ‘Check your ego! / Check your ego!’ Hours later, I reached through / the bathtub’s cold water to let it all drain out” (53). “Distraction Poem” is revealed, at the last, to be a poem about “the fact of motherhood, the fact of children, the body that became multiple” (12). Distraction is a privilege in the bathtub, a much-needed aesthetic indulgence. Cast-iron pastoral. You get out of your head by filling it up. Outside the tub, distraction is an enhanced form of attention predicated upon a commitment to care for others, including (but not limited to) small children.

For years, Burdick’s children, Hazel and Arthur, have served as her Muses of the Surreal in miniature. In fact, the title, Book of Short Sentences, is borrowed from Alice’s daughter. As Burdick explains,

There is much about having small children … that is very disorienting. One has to be alert and present at all times, all hours, and this can lead to a chaos of feeling sometimes. Deep happiness and deep stress. If that isn’t a derangement of the senses … I don’t know what is. … It is totally surreal having kids, yes. I mean just in the most explicit way: ‘Please don’t walk down the stairs backwards with that stud-finder in your mouth’ — that kind of thing.[15]

In “Voices of the Familiar” (from Holler), Hazel and Arthur are pintsize Orphic figures, translating objects into language: “Musical notes, sings Hazel, / and Arthur says water / when he sees ducks.”[16] In “Banal” (also from Holler), Burdick admires how the irritable and irresistible screams of a toddler possess “a logic that comes and goes. Waves of understanding / and intent.”[17] Once more, in Book of Short Sentences, children populate her poems (“Declarations,” “Rain Days,” “Their bodies in mine,” “Flight details,” “The rules”), none better than the harrowing “Nosferatu, kindergarten.” What a macabre title, creating an outrageous correspondence between an Edenic educational environment and tropes of vampire cinema. It’s fearless. It proposes that children, too, can be cruel “monsters,” “vampires / in a kindergarten movie”:

Industrial

rug soaks up scared pee from the kid

who cannot close her eyes.

Abacus, macaroni, tiny scissors,

popsicle sticks, Mighty Mouse, friendly kiss.

The violence of children,

the passivity of children.

The quiet authorities

who do not protect. (119)

As the innocent list of classroom tchotchkes grows fangs in the shadows of F. W. Murnau’s German expressionism, the poem reveals itself as a critique of the educational philosophy of benign neglect.

The threat of violence extends from the schoolyard to the environment. Like many Canadian poets in the age of BP and Kinder Morgan (e.g., Stephen Collis and Adam Dickinson), Burdick fears ecological disaster at global and local levels. In “Trick the World,” she writes,

We want our world to see

where we’re at, standing tall on petty glee,

grinning wildly at the mess we can’t stop

making. (97)

The end-of-times vibe seethes throughout the collection: see poems like “Drink Up,” “Nature Poetry,” “Disaster Protocol,” and “Revelation I.” The dazzling sequel, “Revelation II,” is Burdick’s translation of the New Testament. It begins,

… a corona of spritely donkeys

swinging chains and baying carols

into the smoke that lifts us high

where we belong, where the clouds

flip through our notes and thumb

our pages. (30)

This parody of Christian eschatology and exegesis is obscenely cartoonish. More Warner Bros. Looney Tunes and John Ashbery than John the Apostle’s fire and brimstone. The angels are asses, and the clouds are prickish literary critics — not benevolent Gods who will take pity and rescue us. In the second stanza, Burdick’s tone radically shifts:

We never thought of that.

That the end might be boring

to the earth’s eyes. Ends happen

all the time, they finish us daily. We get old,

breath stops. Sweet retrieval

of constant concern — who is this angel

of the end times? Just the big old

global brain and its squad throb

on a basic axis, sending visions

into the mist. Hail the end —

it’s just the season

to get lit. (30)

The meditative, playful, and completely endearing passage strips the apocalypse of its Michael Bay-sized spectacle, thus making it almost quaint. It’s a small, intimate party with friends and family dockside at the cottage. As Burdick so eloquently writes in the final line of “Disaster Protocol”: “[T]he fire continues and the light does, too” (106).

And there is light in Book of Short Sentences. I’m thinking of “St. Mark’s Wildlife Refuge” and “Surprising Bodies.” The former documents a trip to the sprawling refuge in northwest Florida, just outside Tallahassee. There are obligatory references to birds and gators, even the lovely butterfly garden. But the poem ends with talk of a rather inspired raccoon that will earn future comparison — rightly so — to Robert Lowell’s skunk (“Skunk Hour”) and Elizabeth Bishop’s armadillo (“The Armadillo”): “This huge life — and one fat dismissive raccoon / ambles diagonally down the road, / drunkard aiming for a straight path” (20). “Surprising Bodies,” too, is touchingly optimistic: “We humans,” writes Burdick, “are big fans of hope, aren’t we, / each time we breathe / it’s a further chance” (44). The inflected uptalk of “aren’t we,” at the end of the line, suggests Burdick is somewhat disturbed — if also secretly delighted — by this masochistic hope for the future. In the last ten lines of the poem, she discovers an elegant, multipart metaphor for the pneumatic spirit that inspires:

Hobbled on the intake, stuck

there, frozen in a pause,

such a window, jammed.

But then the bird perched there —

something, what, a kingfisher

or grackle, or a hummingbird —

forces the window open,

the breath out, the body up

and through the air,

all impulse and simple pulse, again. (44)

The concluding image is Kant’s dynamic sublime: “nature regarded as might.”[18] It’s also a moment of mythopoiesis embedded in the everyday. In typical Burdick fashion, she delivers it without much pomp or fanfare. Metamorphosis as natural as breathing. Burdick becomes a kingfisher, or grackle, or hummingbird. She takes flight, “all impulse and simple pulse, again.”

Note: I am listed in the “Acknowledgements” section of Alice Burdick’s Book of Short Sentences. I did not read or comment on the poems in manuscript form. I am thanked because I invited Burdick to visit the University of North Carolina, Wilmington, as a part of a reading series primarily focused on Canadian poetry. — Alex Porco

1. George Eliot, Felix Holt, The Radical (New York: Worthington Co., 1890), 50.

2. Alice Burdick, Book of Short Sentences (Toronto: Mansfield Press, 2016), 121.

3. See Rachel Blau DuPlessis, Blue Studios: Poetry and Its Cultural Work (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2006), 223; Rachel Blau DuPlessis, “The Critique of Consciousness and Myth in Levertov, Rich, and Rukeyser,” in Shakespeare’s Sisters: Feminist Essays on Women Poets, ed. Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1979), 280–99; Rachel Blau DuPlessis, Genders, Races, and Religious Cultures in Modern American Poetry, 1908–1934 (New York: Cambridge UP, 2001).

4. Ezra Pound, “A List of Books,” The Little Review 4, no. 11 (1918): 57.

5. Pound returns to the concept of logopoeia in his essay “How to Read” (1927). See The Literary Essays of Ezra Pound, ed. T. S. Eliot (New York: New Directions, 1968), 15–40.

6. Alice Burdick, Covered (Toronto: Letters Press, 1994), np.

7. Alice Burdick, Surreal Estate: Thirteen Canadian Poets Under the Influence, ed. Stuart Ross (Toronto: Mercury Press, 2004), 158.

8. Karen Solie, Pigeon (Toronto: House of Anansi, 2009), 45.

15. Alice Burdick, interview by Alessandro Porco, Open Book: Toronto, May 29, 2012.

16. Alice Burdick, Holler (Toronto: Mansfield Press, 2012), 21.

17. Burdick, Holler, 26.

18. Immanuel Kant, Critique of Judgment, trans. J. H. Bernard (New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 2007), 61.