'The woman is here to stay'

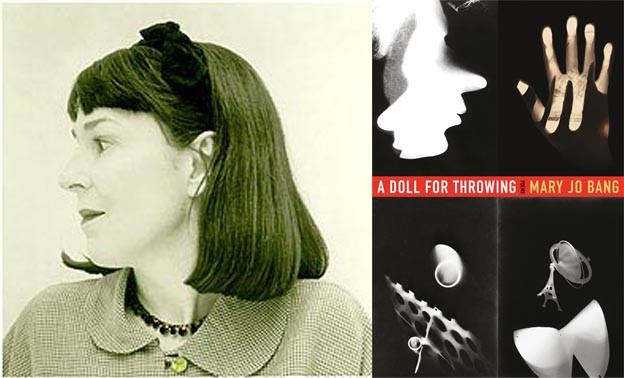

A review of 'A Doll for Throwing' by Mary Jo Bang

A Doll for Throwing

A Doll for Throwing

As she did in her 2004 collection, The Eye Like a Strange Balloon (Grove Press), Mary Jo Bang once again calls on her visual vocabulary — and background as a photographer — to portray various aspects of the Bauhaus, the short-lived German art school: its utopian vision, its Nazi-led shutdown in 1933, and its undeniable legacy. But Bang is in no way limited to this period of artistic influence; in fact, the collection as a whole meanders through a visual and theatrical history of the years preceding the Bauhaus, and the years that followed, landing, finally, in the contemporary setting, with a proverbial middle finger to the current leader of the democratic world: “The last I / saw of the sky, the moon was a man with / moronic orange hair dressed up in a frock coat / and collar swearing to serve no one but himself … ” (from “In November We Inched Closer,” written on November 9, 2016).[1]

In the acknowledgements, Bang describes how seeing Lucia Moholy’s photograph, Untitled (Walter and Ilse Gropius’s Dressing Room) (1926), on display at the Pulitzer Arts Foundation sparked the initial murmurings for this book. This image — also reproduced in the final pages of the book — introduced Bang to the work and world of Lucia Moholy, the first wife of the highly influential painter and photographer, László Moholy-Nagy. Moholy taught at the Bauhaus alongside her then-husband after introducing him to photography. Recognizing her talent, Walter Gropius, the Bauhaus’s founder, asked Moholy to make photographic documents of the new art school buildings in Dessau and some of the objects that were being produced. When the school was closed under the Nazi regime (who denounced the school as “degenerate”), it was thought that many of the images and their negatives had been lost. After fleeing to the US, Gropius later began to use many of Moholy’s images for Bauhaus monographs he continued to publish in his new home. Her name was never attributed to these early images, despite being promised that she would retain the rights and receive fees for any future reproductions.

The story is not unfamiliar: husband and wife form creative duo; wife works just as hard as husband but is relegated to the background; husband gains notoriety; wife is forgotten, or worse, erased. And in some ways, this book is a kind of quest to rewrite this story with Moholy at the forefront — or, at the very least, on equal footing in our collective artistic imagination. Bang brings the lack of equality into awareness with great alacrity in a poem called “The Possessive Form”:

In [year], the ___________s [plural form of husband’s

last name] moved to somewhere; it was there she

did something. From [year] to [three years later], she

was also made [title] at [school name] in [place]. In

[year] she left [one country] via [one country] for

[one country], and as a [occupation] soon made a

name for herself, being compared by some critics to

[woman’s name]. She also lectured to students at

[school name] and [school name], both in [city

name], the emphasis being on the [specialized

subject within the subject]. (37)

But perhaps the point that bears repeating here is that so much of this book was sparked by seeing. Seeing Moholy’s résumé in her archives inspired the poem above, for example, and Bang seems to do a lot of her thinking by way of looking. Many of these poems are based on images, or take images and theatrical settings as their starting points. And although these starting points are vast, often obscure, but nonetheless interesting in and of themselves — Oskar Schlemmer’s Triadic Ballet (1922), a photograph of Niura Norskaya by Lotte Jacobi in 1929, a song from Jacques Offenbach’s opera, The Tales of Hoffman (1881) — Bang is in no way limited to ekphrasis; these poems are not simple descriptions. The various other artistic formats are very much starting points for what happens next. At times, the reader is lead towards something of a narrative, such as “Self-Portrait with Others” (in which the “I” may or may not be Moholy herself):

Before I moved out, there were five of us: me, my

sister, my mother, my brother, and the man who

modeled what we were all to think. He said we

are nature, like it or not. Sun, clouds, rain, and

reeds like those monks used to show their humility

back in the Middle Ages. (6)

At other times, Bang performs a kind of collapse. In “The Doll Song,” she takes a song from Offenbach’s The Tales of Hoffman, which was once filmed by Moholy. But rather than relaying it, she starts with description — “A stage set, curtain, window, wall, the shape in a shadow / drawing the eye into the dark” (25) — and then turns both the visual and the starting point in and on itself:

When a well-lit bamboo lattice expands, it can morph into

Madame Butterfly. On the enlargement of the still, you see a lake

shape on the upper right, the realm of nature. You’ve seen this

opera before. There’s a ship on the lake, a god in the house. A

man is going away. The woman is here to stay. We all want her

to be more than just a loveable glass-eyed facsimile, a robot

going through the motions. (25)

Bang’s book is poetic renegotiation with hegemonic artistic traditions. With lines like this Bang alludes to the potency and agency of the female in the patriarchal history that dominates Moholy’s story, but also draws attention the conflict that women have had to weather in these settings. Yes, the “woman is here to stay,” but can she stay only if she maintains something of the “loveable glass-eyed facsimile”?

Although there’s a lot to hang our hats on in here and elsewhere, there is a slipperiness to the language that Bang plays with throughout the book. Abstractions abound throughout the book, and we’re never quite sure how to categorize what precisely Bang is doing. Bang herself admits that the book does not claim to be a biography of Moholy: “these poems are not about her but were written by someone who knew of her,” she states in “A Note on Lucia Moholy” (65–66). And although the book is so populated with historical figures, the “Disclaimer” states that “Names, characters, places, events, and incidents outside the Notes section are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events is purely coincidental” (73). Purely coincidental … ? It’s a common disclaimer, of course, particularly in such a litigious society as the US, but it does seem a bit of a stretch; even the disclaimer is slippery.

While the numerous notes to the majority of the poems do help orientate new readers, they also give some insight into the complexity and almost associational nature of Bang’s approach to her poetics. The note to the poem “Portrait in the Form of Ephemera,” for example, makes reference to both a black and white photo of Alan Turing and an article by Moholy. The only connection I can make out between these two seemingly disparate elements is that they are from the same year — 1946. The poem seems to suggest that these items were placed “in an envelope” together, as it gestures towards parts of both image (“a photograph of two, four, / six, eight, nine boys boarding a bus”) and article (“paper, six clean / sheets, a monogrammed envelope”) (20). Nothing is made explicit; imaginative gesture is Bang’s modus operandi.

This slipperiness is also reflected in the title, which she takes from a doll, or Wurfpuppe, designed by another female Bauhaus artist, Alma Siedhoff-Buscher. So we’re told on the book’s back cover, this is a doll that is a “flexible and durable woven doll that, if thrown, would land with grace.” Bang’s treatment of language is similar: she throws in so many subjects, ideas, and images, and yet, with her formal flexibility and durability, brings the poems to also “land with grace”: “Knife to the narrative root, a pillow over the aperture / opening” (9); “The mosaic ceiling above us is a blue overturned / bowlful of goldfish. Each open mouth is a blind / spot. Want. Want. Want. I catch sight of myself / in a mirror” (7). The book’s title also reflects a kind of imperative, particularly in the case of the subordinate female figure. She too must land with grace: “I understand men. / Some like to have one woman in their arms, / while a second one stands on a half-shell, both / continuously shifting between being and being / seen” (14).

Bang’s latest book is a lot of things, and it does all of these with adroitness and an impressive depth of consideration. On the surface, it is a veritable exposé of what the prose poem is capable of: the whole book is made up of these delightful containers — representative of the exquisite boxiness of many infamous Bauhaus buildings — and yet because of her treatment of the line within these small boxes, it is never heavy-handed. It is also a wonderful example of how visual art, architecture, and, specifically, modernism, can provide such a rich source for the poetic imagination. Finally — and perhaps above all — A Doll for Throwing is a political statement, returning erased and forgotten names to the forefront of the story, reinserting women into a male-dominated domain while also exploring the impact of these great artistic legacies on our cultural and imaginative traditions. Under her expert poetic gaze, these systems start to undo themselves. And for the better: “the dress is no longer the / thing the future is founded on. You put it on. / You take it off” (31).

1. Mary Jo Bang, A Doll for Throwing (Minneapolis, MN: Graywolf Press, 2017), 58.