Of what use these memorials

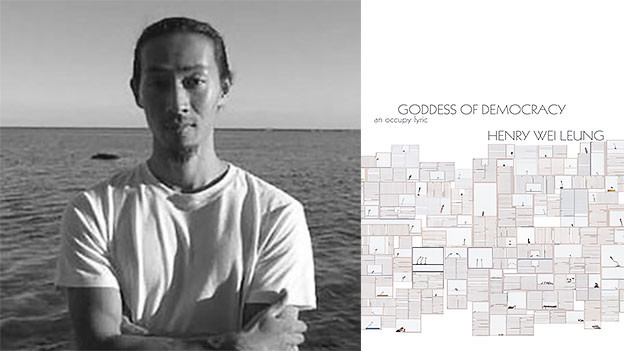

A review of Henry Wei Leung's 'Goddess of Democracy: An Occupy Lyric'

The Goddess of Democracy: An Occupy Lyric

Goddess of Democracy: An Occupy Lyric

For most of the fall of 2014, Hong Kong’s streets were filled with tens of thousands of protestors in one of the grandest displays of political resistance in modern China’s history. The so-called Umbrella Revolution was a fight for a universal suffrage under the “one country, two systems” plan that had been in place since Hong Kong’s return from British colonial rule to China in 1997. As part of this plan, mainland officials in Beijing had promised Hong Kongers the democratic right to elect their own top official by 2017, a promise that was essentially reneged in September of 2014 when Beijing announced it would only allow a handful of prescreened candidates to run. Hong Kongers took to the streets.

Henry Wei Leung’s Goddess of Democracy explores Hong Kong’s political uncertainties as primarily exposed by the Umbrella Revolution, deploying sophisticated poems fraught with political (and personal) ambivalences that he grounds through copious journalistic explanations of various events via epigraphs and one dedicated prose section. Through this simple combination of lyric and documentation, Leung’s book simultaneously seeks and challenges the viability of the historical moment as one supposedly situated within a coherent political narrative. It sings the anger of revolution, but with a distinct dissonance, a song that both wavers on the edges of noise and is attenuated by memory’s density.

These poems employ numerous forms: some look like erasures, some include redactions, some are prose, some are lineated, and so on. But the prevailing mode is lyric, and really a lyric that assumes very familiar traits: often in the form of address, striving toward revelatory image, and exploring experience as a kind of phenomenological event, as a form of meaning-making. Most often, these lyrics specifically address the Goddess of Democracy statue, which was constructed and then razed during the Tiananmen Square Massacre of 1989, and of which there have been many replicas in various locations. Here is an exemplary moment from the poem “Victims of Communism Memorial, Washington, D.C.,” which is preceded by the explanatory epigraph, “G.O.D. replica raised in 2007”:

I remember floating like a desert

in a box on the sea, where to see

a coming storm was to see the land

erasing: a perfection; and perfection

could not save us and the storm is

always coming and I sing the storm.

I sweat at your feet in a gulp of smoke

released, a halo of solitude, counting up

old receipts, a victim too of communism’s

cheap memorials. We are the cobweb

shaking loose on sideview mirrors,

the clock tower pining, the empty quiver.[1]

This poem reflects many of the dynamics and gestures that constitute this book’s project. The title endeavors toward both geographic and historic specificity (a visitation to a specific memorial on, we assume, a specific occasion) at the same time that it points toward geographic and historic multiplicity (the victims of communism spread across many regions and the instances of victimhood across many periods). And while this specific visitation is the occasion for the poem, the reader can see Leung uses it to initiate a deeper vision, one of archaic weight (desert, sea, coming storm, etc.) so dense with its own pregnancy that the memorial itself is quickly lost. This is, in many ways, a traditional poetic response: the flight to the archaic is an appeal to something ancient and lasting in the face of contemporary uncertainty. But it is energized by Leung’s innovations, which feel both challenging and precise. Such innovations in the above quote include the surrealist twist of “a desert / in a box on the sea”; the subtle grammatical transgressions that rush the line “and perfection / could not save us and the storm / is always coming and I sing the storm”; and the abrupt transition out of the archaic and into the contemporary in the latter two stanzas, which introduce a slightly more unwieldy, more modern (uncooked by history, we might say), lexicon: “gulp,” “receipt,” “cheap,” and so on. This shift in lexicon signals an awakening back in the present and an attending narrative, but we can’t quite suss out what is going on when we’ve opened our eyes. “Sweat” certainly makes us think of some of kind of exertion or duress. Being at the memorial’s feet suggests pilgrimage and supplication. The “gulp of smoke” suggests tear gas or smoke bombs, or maybe simply a cigarette. Then this whole business of counting or keeping score, economic transaction as a condition of cultural memory, and, finally, this peculiar progression of three images: “We are the cobweb / shaking loose on sideview mirrors, / the clock tower pining, the empty quiver.” The cobweb shakes because the car is starting up, or maybe because a bomb has exploded nearby (also here is the idea that the sideview mirrors — the way of looking back — have been choked by disuse, and the poem or the moment is dislodging that, asking us to use them again). The clock tower is a sniper’s rook but also a classic image of a moment of reckoning. And then the quiver, as in a quiver for arrows but also the body quivering (alluding back to the shaking of the cobweb).

Leung flirts with images of militancy and civilian/civil disobedience but never fully commits the poem (the lyric) to such service — here and in many other poems the political finds itself back with the person, the poet, the individual in the midst (a “halo of solitude”) of these happenings. The individual within a politics is a complicated subject. For Leung specifically, the American poet-activist of Chinese descent, it is a question of his rights and responsibilities to engage a political movement that he is only partly a part of, that in many ways he was privileged — via support from a Fulbright — to witness and participate in. This kind of intermediary status, conditioned by privilege but also exclusion, is a constant query in these poems and animates the lyric “I” toward its various destinations. In some moments, Leung exhibits extraordinary care with his position and what it entails, as we can see in these lines from “Disobedience”: “I stood inside / a silent night of cell phone lights / with all my hands / hanging. For the record / I told the foreigners nothing / when asked. I looked / like someone to ask” (20). Elsewhere, Leung pushes examinations of the intricacies of the political self into far less controlled, more exploratory regions. At times, it has tremendous results, as in this extraordinarily rich moment, the second of two blocks of prose, in the poem “An Umbrella Movement”:

The body vanishes. Who is not free. No one is not free. An other is not the seventh-person pronoun. The people is not the seventh-person pronoun. There are no more pronouns; only anonymity. It was like writing letters from a rooftop from which many had jumped before me. Suddenly I realized that not belonging in the world is not enough. I did not belong in two worlds, perhaps three. I let each letter fall, great post of gray trees. Perhaps loneliness can well so deep that it becomes joy. (41)

This quote exhibits another important aspect of the poems in this book: their compulsion toward negation (as another example, one might look to the section titles, three of the five of which are of a “neither/nor” structure, as in section IV, “Neither Self Nor Not Self Nor Both Nor Neither”). Here negation culminates, perhaps, in the haunting image of the rooftop jumpers and the poet’s conclusion: “not belonging in the world is not enough.” But this pivotal image and conclusion are supported by a quickly sketched but nonetheless complex web of contextualizing concerns. Leung is obviously interested in the way language conditions identity, collectivity, and otherness. There is the idea of freedom (and, interestingly, its inescapability). There is the idea of correspondence from the “front” (in this case, the rooftop). There is the simultaneity of worlds and the idea of “belonging” (somewhat cheekily subverted here, a bit of negational legerdemain). And loneliness, which we consider a pervasive condition of political life for many. Negation is populated, as it were, by all of these elements. And Leung executes their progression movingly, from analytical play toward witness of human suffering and the tragic conclusion of suicide; then this heartbreaking silence that follows, alone, because everyone else has killed themselves; and then finally, improbably, or perhaps as a feat of hope, the possibility for joy, the need, in fact, for it.

The above excerpt captures a particularly immediate moment of negation in Leung’s lyric exploration, but the concept of negation shades many of his concerns, especially that of cultural memory as it is imbued in the figure of the statue. As I encountered the various Goddess of Democracy statues and other monuments Leung describes or addresses in this book, I could not help but think about the many statues I’ve seen that either have no face or have faces whose details are grossly simplified. Some statues are situated on perches so high above or far away that it’s simply a practical choice, but it can also be said that facelessness broadens a statue’s symbolic reach as a representative of a general populace. This is something of a rule of human beauty, too, which favors symmetry, evenness, no real identifying characteristics. Perhaps we find such faces beautiful because we can more readily see ourselves in them; they are a smoother surface upon which to project our own selves (or, in the very least, such faces don’t insist upon their own uniqueness). Of course, this is a complex issue: facelessness both expands the inclusivity of representative work yet also nullifies that work (it is both and neither, neither both nor neither).

And Leung alludes to facelessness throughout this book. He laments “a whole adolescence sitting by monuments ignored and covered in bird shit” (56). He sings to a Goddess of Democracy statue that “there is no man / who ever sees you, goddess” (33). And he foretells, for himself, that “by this time next year / I’ll have no more face,” which he exquisitely complicates just a few lines later with a play on “face” in his address to the goddess: “One day, I’ll face the truth. / But if the truth excludes you, / let me face you” (82).

What can we make, however, with this facelessness and negation as they condition an object of memorial, whose purpose is indeed to give face to a struggle, to preserve the remembrance of a history and a people? On one hand, Leung seems to chastise those who willfully ignore history, insinuating that history is there waiting to be attended to and learned from. But one could also see this facelessness as endemic to history itself, that history’s coherence and recognizability, its clarity and readiness for understanding, cannot necessarily be assumed. It is within this difficulty that these poems ultimately find themselves. They express the uncertainties not only of Hong Kong’s political future but its political past as well. Those who endeavored toward justice — in Tiananmen Square and the Umbrella protests alike — did not exactly fail but saw their projects fragmented, dispersed, made into replicas, and so on, all while caught up in one of the grandest narratives of the twentieth-century, the contest between the behemoth adversaries of communism and capitalism. Forged by the titanic pressures of such political forces, memory — as our late history has shown us — is made incoherent. It is improvised and expediently deployed, and as such it is constantly being ignored, rewritten, emptied out, erased, or worn down.

Lyric poetry is precisely the right response to this incoherence. Leung exhibits this marvelously. He takes whatever might remain, whatever faintest trace of truth or reality, and attempts to make of it something viable, a way forward, an incremental bettering or even a transcendence. Maybe. I’d think Leung would not be so reckless as to dictate any sort of future. Rather, he looks on what the poems have enabled, even beyond his intentions, and lets them lie in front of us. In the final poem, “Dedication Endnote,” he writes: “I never meant to be this kind of ghost, holding, / Out of sequence, your secret freedoms” (94). Perhaps it’s this idea of “holding” that grounds us — a small gesture of preservation, a keepsake we hide away while the monuments around us tumble.

1. Henry Wei Leung, Goddess of Democracy: An Occupy Lyric (Oakland, CA: Omnidawn, 2017), 35.