'The protests became a poem'

Liu Waitong's 'Wandering Hong Kong with Spirits'

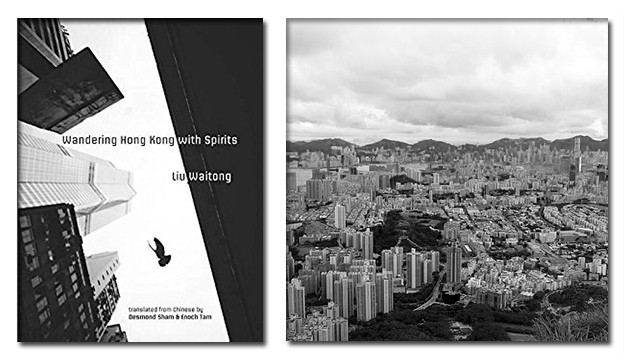

Wandering Hong Kong with Spirits 和幽靈一起的香港漫遊

Wandering Hong Kong with Spirits 和幽靈一起的香港漫遊

What is it to be a Hong Kong poet writing now? Specifically, a Hong Kong poet who grew up over the border in Guangdong, who has lived also in Beijing; whose poems register the pull of other cities from Lhasa to Paris, and the pull of China not only as a literary inheritance all the way back to Zhuangzi, but also as a geopolitical giant changing daily even as Hong Kong itself changes? For Liu Waitong, it means to be accompanied always by ghosts. But it means also to seek them out and keep them company in turn — to haunt with them. Working through questions of displacement, citizenship, and competing visions of Hong Kong’s and China’s future, Liu’s poems insist that a careful attention and receptivity can be revolutionary. For Liu, that attention is what we owe our pasts and each other.

Wandering Hong Kong with Spirits is the first collection of Liu’s work in English, after eleven poetry collections published variously in Hong Kong, Taiwan, and mainland China over the last two decades, as well as several volumes of essays, fiction, and photography. The book’s namesake is his 2008 collection published by Kubrick Books in Hong Kong, though the English volume is a selection of poems across books rather than a translation of that book in particular. The choice of title is apt for this bilingual introduction to the work of one of Hong Kong’s foremost poets and public intellectuals.

Liu wanders with the shades of poets and revolutionaries, gathered most closely in the long poem “In Time of Peace,” whose first section retraces Liu’s own leaving China for Hong Kong:

We head into exile in time of peace, claiming to the outside

world it’s spontaneous travel. To the inner self it’s all out war

burning an elegance carried within.

People are at odds over commerce and pleasure, while developers

keep turning mountains and rivers into Shangri-las filled with blood,

we keep following the dark colors and slanting strokes —

[…]

Today we have lost China.[1]

The poem is rife with ghosts, unmoored from their historical eras and rubbing shoulders as Liu puns on their names: “Han Bo is not Han Yu … / Gao Xiaotao is also not Gao Shi … / Wang Wei leaves Wang Wei, pretending to defend the border” (57). Against this litany of literary ancestors and contemporaries, Liu juxtaposes the transformation of China’s natural landscape into commodity; what’s left of some poets is only the modern infrastructure graced by their names, the Su and Bai Causeways (59). The poem likens the movements of capital to the displacements of war, becoming an elegy suffused with urgency and lament:

Oh Motherland, in my mind I take care of the vivid smoke,

which is all you’ve thrown at me, which is what I used to pay

for my travel expenses to escape the flames of war. (53)

Hong Kong, in contrast, offers the space and time to slow down the pace of remembering. In “Looking for Woodbrook Villa on Pokfulam Road,” Liu seeks out the home of Dai Wangshu, the modernist poet who lived in Hong Kong from 1938 through the war years:

I searched Pokfield and Pokfulam Roads for an hour,

for your footprints. I even asked a cat for directions.

You walked silently next to me along the way

like listening to a radio of rain. (67)

Liu’s tone here is much more intimate, with a lightness suited to the poem’s relaxed, measured pace. He continues:

All the way uphill, downhill, I’d better explain it to you

in an interrupted frequency of heavy rain:

I too have a silent windowsill and shelves of books,

I have a beautiful wife on another island.

But right now, we are far from these eras,

holding an umbrella, we step on the shadows of flamboyant trees and fallen flowers … (67)

Liu marks what their lives have in common — the silent windowsill, the beautiful wife (who, in Liu’s case, is a well-known Hong Kong poet herself) — but he’s more interested in building, stanza by stanza, a space which can hold them together “far from these eras,” where suspension of time is a kind of refuge and communion:

the mountain stream surges like it wants to tell me everything,

the rain is spilling everything as well,

it’s like one and a thousand spirits are vying to recount it all. (68)

But the moment can’t last, and when it disappears, so does the poet, very nearly; someone exits the house, interrupting, and the poem ends on the line, “I’m silent as a dog whose scent has been washed away by rain” (68).

Liu is known as an allusive poet, in conversation not only with his Chinese poetic forebears but with international literary history and politics. “In Time of Peace” is an homage to Auden’s “In Time of War,” even nodding directly in its first section to Auden’s and Isherwood’s travels in China. In “A Seaside Graveyard: Three Poems,” as Liu wends through Hong Kong’s WWII-era literary landscape, he alludes not only to Hong Kong’s Repulse Bay Hotel, where Eileen Chang’s Love in a Fallen City is famously set, but also to Hölderlin and to Rocinante, Don Quixote’s horse. “Charlie on Temple Street,” a poem characteristically grounded in the details of a specific Hong Kong neighborhood, is subtitled “Or: are we the Taxi Driver?” and Robert De Niro’s character inhabits the poem as fully as Charlie and the poem’s speaker do.

As for political references, there are freedoms other than space and time afforded by writing and publishing in Hong Kong rather than across the border. Many of these poems couldn’t appear in print in the mainland in their present forms.[2] Take, for example, “The Missing,” which bears the epigraph “to Ai Weiwei, and others ‘forced to disappear’ in China.” The poem’s language tilts from Liu’s more typical conversational mode into a rare soaring:

Yesterday’s protests are written across my body, the protests became a poem.

Let the ice saw cut all the way into the tree’s dream,

let the horse look at its own footprints on the water like silver foil …

the stroller who rose up early disappeared into the mist like horses,

the mist attempted to stride with its staggering hooves like an unborn nation,

still searching for riders among us. (143)

Christopher Mattison, the director of the Atlas series of translations of Hong Kong Chinese literature into English, points out in his introduction that it would be a mistake to brand Liu primarily as a political poet. Rather, Mattison says, Liu is a careful observer of Hong Kong, and many things in Hong Kong are inherently political. Perhaps it’s just a matter of emphasis, but I’m not certain that I agree with Mattison here; while it’s true that Liu is indeed a “poet of longing,” as Mattison suggests, “of past eras, former loves, lost neighborhoods, and poetic mentors” (xvi), nothing on that list is separable from politics in the poems or in Hong Kong more generally. When Liu elegizes the demolished Central Star Ferry Pier, for example, he is not only lamenting the loss of a familiar landmark, but also pointedly indicting Hong Kong’s real estate market, which incentivizes the replacement of historic sites with new, more profitable development. In Liu’s poem, the pier shakes its head and sings into the cold rain: “It all will finally disappear to become a postcard sold / for ten dollars. This Hong Kong will disappear and become real property / with an unspecified mortgage” (93).

The act of writing itself, of course, is saturated with the politics of language; that’s true anywhere, but true of Hong Kong in unique ways. Hong Kong’s dominant local language, Cantonese, is a minority language. As Beijing gradually chips away at Hong Kong’s political independence, so Mandarin becomes more pointedly an agent of soft power. Because a poem written in traditional Chinese characters can be read aloud in Cantonese or in Mandarin, to assert that a given poem is Cantonese is to make a political distinction that will be received differently in Hong Kong or in Taiwan than in the PRC. [3] Liu has said that some of his poems are written in Cantonese and some in Mandarin.[4] Which poems these might be, and how that may inflect their meaning for various Chinese-language audiences, will be mostly lost on English-language readers. But then, English in Hong Kong is political, too, and the several translators of this volume have made some choices that English-language readers are more likely to apprehend.

Hong Kong’s English has its own idiom distinct from, though drawing on, the many other Englishes which circulate in the city: British, American, Canadian, Singaporean, Filipino, Australian. Rather than translating into what Lawrence Venuti would call “smooth” English, Liu’s translators have brought his poems into Hong Kong’s particular ever-evolving idiom. A good example is “Poem for the Universe’s Prostrating-Walk,” whose epigraph explains that the poem is about a protest against the mainland–Hong Kong Express Rail Link. The 2010 “walk” in question was modeled on the Tibetan mode of protest more often translated as a “prostration march.” But Hong Kong’s English-medium news sources, as they covered that local protest and others, used the term “prostrating-walk.” [5] It is a Hong Kong English word, not these translators’ invention.[6] Another example is the word “stroller” in the line quoted above from “The Missing.” American readers are likely to first imagine what British readers would call a pram, but here, “stroller” is the nominalization of the verb “stroll,” and because of the influence of British English, it’s unlikely that a Hong Kong reader would think of babies or wheels rather than a walking person. The Atlas project’s choice to translate into Hong Kong’s English is an inherently political decision, and is neither a given nor an accident.

It’s fitting, for a poet so accustomed to crossing linguistic and national borders, that the most intimate spaces in these poems, if not the most comfortable, are the liminal spaces of airplanes. Two poems are dedicated to Cao Shuying, Liu’s wife, and they, among several others, are both airplane poems. Here are the final stanzas of the book’s penultimate poem, “Drafting a Doomsday Poem,” subtitled “for Shuying”:

Our plane is floating

Silver rays from the stratosphere

dancing lightly amid sharp blades

a thousand mountains from destruction

a thousand seas from rebirth

quietly watching civilization

closing rose buds

my dear you watched those

millions of stamens and pistils

breeding in raging flames

When coldness comes back

a new home under a whalebone

will protect a non-existent you

and me from the naked sun

writ yesterday in water from memory

to find clues in books of sand

to recite poems without words

to perform for white dwarf stars

lithe and graceful as Nijinski (149)

This “Doomsday Poem” imagines its apocalypse not as an end, but as a radical, voiding renewal experienced in the company of the beloved. It’s a grand elegy — this book is full of them — but at the same time it’s a delightful, almost carefree, love poem. And this doubleness is one of the most appealing elements of Liu’s poetry; throughout these poems, in their dark observations of China’s and Hong Kong’s and the world’s politics, in their mourning for lives marked by those politics, Liu’s faith in poetry and in poets is a steady, full-hearted through line. Poets still “find clues in books of sand” and “recite poems without words … lithe and graceful” even if they have become “non-existent.” Even after the end of the world, what poets do is haunt: they mark time, they remember, they conjure the power of language to animate and to attend. And always, they keep company with others and the world.

1. Liu Waitong, Wandering Hong Kong with Spirits (Hong Kong: Zephyr Press and MCCM Creations, 2016), 51.

2. It’s important to note that the question of censorship is a complicated one; Hong Kong’s publishing industry is small and governed by fairly strict obscenity regulations. A manuscript may have a better chance at publication in the much bigger, and in some ways more open, publishing market of the mainland. Hong Kong writers are astutely aware of factors ranging from censorable content to market forces, which make a book more or less publishable in each market, as well as in Taiwan. Like Liu Waitong, many writers publish in all three. His poem “The Missing” has, in fact, appeared online in the PRC — minus its epigraph. I owe thanks to two other Hong Kong writers, Lee Chi-leung and Dorothy Tse Hiu-Hung, for their insights here.

3. Like the question of publishing markets, the significance of Mandarin versus Cantonese is complicated. For one thing, Mandarin is Taiwan’s language as well as the PRC’s — Mandarin isn’t always coming from the mainland. Some characters are unique to Cantonese, and if a poem uses those, it’s identifiable as a Cantonese poem, but not all poems may feature those characters. The boundary between languages is often not clearly visible, and as Hong Kong–based translator and scholar Lucas Klein points out, sometimes the only way to discern which Chinese a given Hong Kong poem is written in is to ask the writer (Lucas Klein, “‘One Part in Concert, and One Part Repellence’: Liu Waitong, Cao Shuying, and the Question of Hong Kong and Mainland Chinese Sinophones” [forthcoming, Modern Chinese Literature and Culture, Fall 2018]).

4. Liu Waitong, “The Translator and the Translated,” spoken remarks, November 4, 2014, Hong Kong International Literary Festival, The University of Hong Kong.

5. An example: Time Out Hong Kong. See this open-access essay by Steve Kwok-Leung Chan of SIM University Singapore for a detailed account of the recent history of Hong Kong prostrating-walks.

6. For a sample of the playfulness with which Hong Kong English can interact with Cantonese, check out Kongish Daily.