Expression Concrète

A review of Divya Victor's 'Natural Subjects'

Natural Subjects

Natural Subjects

Divya Victor’s new book Natural Subjects deconstructs the relationship between sentimental notions of authorial authenticity and normative models of citizenship in a way that will add some much needed bitters to your cocktail, at least if you can stomach it. The book is therefore, on a theoretical level, an absolutely refreshing and uniquely contrarian read. But on the level of the sonic and textual, it is also one of the most sumptuous, expressive, and musical books to come out of experimental poetry in recent years. Particularly in a world where postmodern and hybrid and post-selfie lyric is always already so banal as to have lost its musicality, and the sheerly conceptual has forsaken music.

To return to music in poetry means to return to the concrète — signification for the sake of signification, not for the sake of concept or lyric or parodic postmodernism (gestures that are all too communicative).

It helps that the book is topologically set up like a musical score, with alternating text sizes and placements, plus a multitude of references to old popular songs from “one little, two little, three little Indians” to “Do, Re, Mi” — tunes that forge a passport examination of cultural literacy, an exam that seems to never end, even after the passport is received and authorial identity is created.

What do we expect from the author, from her photo, from her bio; how do we assess Victor’s literacy, her ability to sing the songs that we know, so that we can have a politically resonant connection with her, so that she can have connection with us, and so that we all can commiserate over a leftist political problem? These questions are repeatedly provoked in this musical book, through rumination on the problematics of the passport and the author’s photo and identity.

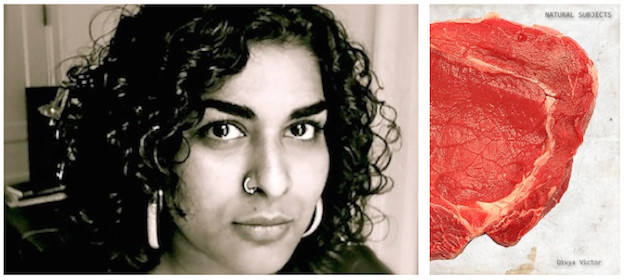

Instead of answering directly to the interrogation of the questions that arise, Victor gives us shocking detours, like a cover image of red meat, as if to mock our impulse to have a humane author-reader connection. Her title, Natural Subjects, so clinicalizes our demand for the natural subjective position of the authorial self that it makes us feel a bit wretched for wanting it. As with Kim Rosenfeld and Trisha Low, the clinic, law room, diary, and church are all sites where identity is born and bred but also resisted, even if this resistance itself becomes a form of authorship, a way of singing. But drawing too from the imaginative dialectics of dialect that infuse the poetry of Douglas Kearny and Julie Patton, as well as the neon art of Glenn Ligon. Enter here Eliza Doolittle’s mispronunciations, that cute show of cockney Englishness, which are peppered throughout Victor’s book and serve as inspiration for her own misheard lyrics.

As with Victor’s earlier book, Things To Do With Your Mouth, instructions are not only sites of grooming, care, and domestication — they are sites of cruelty, discipline, and force, as well as resistant authorial standpoints. But this resistant authorship does not give the reader a “natural subject” espousing caps-locks politics. Nor does it mean you’ll get levelheaded quotidian slice-of-life poetics.

Victor’s “I” is speculatively tuning itself against your expectation, picking from different misheard tunes, and different poetic styles — and the tuning, as in Kieran Daly’s music, is itself a site for the production of musicality.

Here Victor tunes her I:

I is a period of continuous residence and physical presence in the United States

I is a knowledge and understanding of U.S. history and government

I is an ability to read, write, and speak English

I is good moral character

I is an attachment to the principles of the U.S. Constitution

I is a favorable disposition toward the United States (24)

Victor’s making of sonic and textual musicality out of expressive and legalistic confession is a new form of concrète poetry that aligns with the work of Low and others working across a post-conceptual spectrum. It bears no comparison to the New York School and its spin-offs, as it is not quotidian and cosmopolitan in a neutral way. Remembering that concrète poetry is both abstract sound poetry and visual page poetry, and that both types share a diminishment of the vernacular communicative voice, then what is privileged is sonic and/or textual abstraction. And yet, concrète poetry has recently begun to blend in with sites of sensible communication, network-building, and expression. An irony always is inherent in the way visual poetics has parodied advertising, but perhaps less funny when used to uncritically promote contemporary art in glossy books, such as The New Concrete: Visual Poetry in the 21st Century (Hayward Publishing, 2015).

That said, some of the most cutting-edge of books are not forging a vernacular, affective identity or reaching for a gallery-ready idealized notion of “visual poetry.” But rather, are constructing what Low calls the “not-not I” — a redoubled repression of the authentic voice, and the production of the concrete book, diary, media object, or art project. These projects can be epic pastiche (Cecilia Corrigan’s Titanic), explicitly personal (Low’s The Compleat Purge), or frighteningly impersonal (Steve Zultanski’s Agony), but they are never transparently communicative. Which is a real achievement, considering that “non-communicative” aesthetics have become all about communication and coterie, and that confession has become so omnipresent that it ceases to have value. The confessor, like the analysand, is simply irrelevant, and so is the impersonal poet. But with these new works some sort of opacity enters the page and is difficult to handle.

Perhaps the key work to use confession in an opaque manner is The Compleat Purge (Kenning Editions, 2013), which, rather than being an authentic event of the author vomiting up Asian American post-feminist post-Catholic S/M identity and emotion, is about sublimation through the creation of a concrete object, form, or structure. This sublimation manifests at the level of the text as trepidation around modes of procedural entrapment — notably the repetition of the suicide note — confusing the expected authenticity of the vernacular voice while activating sustained concreteness. Songs have terminal duration, though they are repetitious — as Low writes of sex, “It is fleeting, and once satisfied, begins again, a knot at the base of the belly that moves up against your throat.” Still, never one to stay too long in unqualified Eros, Low ends the cited paragraph with “fucking can kill you” (97).

These new works of Expression Concrète build on an avant-garde notorious for questioning the authentic presence of the Other’s voice. English experimental poetics from modernism forward has often been polyvocal to such a point that musical and textual “presence” is forged in spite of the author’s intentions. On the other hand, sometimes such presences are an intended part of the procedure, hence the double meaning of concrète — presently musical and presently textual. In fact, for the post-structrualist avant-garde, mediation (irony, delay, deferral, simulation, imitation) is often as immediate and swift and violent as Artaud’s cruelty.

Expression Concrète qualitatively represses certain kinds of authentic vocality in order to produce objects of study and concentration that remain always polyvocalizable and musical, no matter how legalistic, speculative, communicative, confessional, pastiched, banal, and doctrinal their content may appear. Unlike prior flat-affect art, Expression Concrète isn’t blank or cynical (illustrating some thesis on “performative intentionality”) but always a musical lull back into the unreadable musicality of the concrète text. Since the unreadability of postmodernism is so thoroughly readable, and the detours to identity and affect are even more readable, a new form of opacity arrives.

Some of these new works are simply using gimmicks and are unreadable not for the sake of art but because of a lenient impulse to conventionalize oneself in a scene: this is bad post-conceptualism. For instance, online publisher GaussPDF is chock-full of works that are unreadable because of laziness but also works that are unreadable because of musical genius. One has to parse quite a bit to tell which is which! But if you can parse, the formal complexity you’ll find in the good work is rewarding and new. Though, most critics will default to reading through old aesthetic lenses: affect, irony, and identity, “disruptive communication in the service of canonical continuity,” or else there will be the desire to see things as liquid, fluid, perofmrative, and hybrid (this one is becoming hot in the art world, where poems are thought to leap off the page and, hopefully, into the market). However, Expression Concrète refuses to give an upper-case I/WE to rally around, or a fluid hybrid accessible lower-case “i,” but instead a complex shuffling of expectations and eluding of conventions. Just as Low’s suicide notes unintentionally make for aesthetic reading material, even as they pose as unreadable, grotesque, and violent.

On a different yet related note, poet Emji Spero sources texts about decentralized networks (from Deleuze to mushroom manuals) to produce a coherently visual book of poetry in almost any shit will do (Timeless, Infinite Light, 2014). And Gabriel Ojeda-Sague’s Nite [chickadees] (GaussPDF, 2015) tracks socio-political turbulence in America through Twitter postings by Cher, interrupted by large emoticons — toying with camp and appropriation in a way that is both effective and affective; but also totally visual, with the heartbreak icon particularly jarring and surprisingly poignant after a childlike misspelling, “ERIC GARDNER.”

And then there is Shiv Kotecha’s book Extrigue (Make Now, 2015), which offers a dryer example of the concrete. As “intrigue” means to be led into (in) a trick (trice), “extrigue” disentangles the magic of poetic absorption, and leads us out of the trick. Which is itself a trick. An old one. The text is comprised of caps lock and numbered, painstakingly described “clues” from the movie Double Indemnity, creating a book that is “blank” and “static” (as Steve Zultanksi describes it). Kotecha attributes this to the black and white nature of the film: “With this movie, I didn’t have to gauge between pink flesh or dead flesh, because it was all just a matter of things being lighter or darker than the things they were next to,” and thus, he chose to not to write Salo but instead Double Indemnity. Unlike Tender Buttons, the catalogue here is pulled from VLC media player, pausing the frames, and is therefore a redoubled simulacrum. Nonetheless, when returned to the page, and the site of “authenticity” that the published book of poetry refuses to not be registered as, we get yet another rendering of expression gone concrete: “A GAPING HOLE ON THE TOP AND BOTTOM OF WHICH IS SHINY WHITE FOLLOWED BY SHINY BLACK FOLLOWED BY A FIELD WHICH MUST BE SKIN A SOLID GRAY WHAT IS LIKELY A SHOULDER BUT ONE CANNOT BE SURE THE TIP OF A CIGARETTE THE CLUTCHING OF KNUCKLES THE FALLING OF AN ARM …” Of course, using the term gaping hole comes with its set of heated connotations, but the book continues to play on and through coolness, conveying the confusion of mediated watching, torn between passive visual consumption and active emotional excretion.

In Victor’s Subjects, the demands we place on subjects to become citizens, issued in all caps, also remind us of the demands we place on “authors,” to be good and moral representatives of their subject position:

BREAKING NEWS: YOU WILL REQUIRE AN ABILITY TO READ, WRITE, AND SPEAK GOOD MORAL CHARACTER; AN ABILITY TO READ, WRITE, AND SPEAK A FAVORABLE DISPOSITION TOWARD THE UNITED STATES. YOU WILL READ, WRITE, AND SPEAK AN ATTACHMENT TO THE PRINCIPLES OF THE U.S. CONSTITUTION. (28)

The tedious nationalism of even the most radical Leftist and anti-racist poetic projects in America is given a bit of a shove here, but Victor’s book is not an aggressive affront to demands like “We encourage the subject to have a natural expression” (30): rather, she offers a formally singular revelry that comes after confrontations with formally deadened formulas. When Victor mis-sings the old tune “My Bonnie” as “my body lies over the ocean,” we think of Bonnie, and also the author’s body; then, with “O bring back my body to me,” we think of the disappearance of the body, and how the fort/da game of the authorial body is unpleasant yet engrained in popular song. Was Bonnie ever even there? Is the author’s body present in the text?

These lines of questioning quickly detour as Subjects becomes about the concrete phrases without heeding polemical efficiency:

I swear / because the terrace / is for kites, the verandah / is where we oil our hair / because the lorries have horns / the goats have kept alive / almond and gooseberry / steeped in glass jars / because we measure / the grain with copper, we know / a month ends later / because tables are made … (47)

We shift into Victor’s inner ear, and rather than finding it branded by authenticity or counter-authenticity, lyric or concept, figure or abstraction, or some “quirky” hybrid that balances both — we get a refreshingly new concrète sound, that is both effusive and compact. We stumble into a vision that sounds good, without ever sounding so good that it is easy-listening hybrid crap. Despite the constriction of cultural memory and enforced cultural tunes, the ear continues to work, bending and unbending the landscape of official culture.

ME, a name I call my self (48)

The problem is not that we can’t get rid of the songs that get stuck in our head after they are hammered in (as Henry Higgins hammers “the rain in Spain” into Doolittle in My Fair Lady) — it’s that we can’t get rid of our selves rubbing against the songs; we can’t have pure unfiltered unmediated access to the authentic folk song or authentic national anthem. In Subjects, Bonnie’s body never comes back. The body remains buried, beneath riddles, half-heard memories, and disturbing headstones, passports, and medical reports. By giving concrete form to the lushly mutable speculative/musical back-and-forth motions of memory/selfhood/text/tune — we are reminded not of the liberating potential of poetry to remix normative cultural standards but rather of how subtle the poetic ear actually can be. And how the poetic ear can rub critically up against nationalist essentialism, even as it craves to belong.

The poetic ear does not always produce coteries or prize-winning books or monuments or raise the dead or bury the dead. Sometimes it just produces a little tune. But the littlest tunes can be the most daunting. Subjects reminds that authors, like citizens, no matter how counter-dogmatic, are always groomed, and postured to be “natural subjects,” spokesmen with author photos and proof of cultural literacy. This is theoretically refreshing.

But no great concrète work ends with a theoretical refresher. Taking steps beyond the deadlock of subjectivity, even when writing about “piles of dead people,” Victor uses repetition and variation to forge a remarkable aesthetic kernel out of routine cultural expressions, without being for or against expression, itself. This is a stunning feat and its own sort of coup d’état.